J William M Tweedie

Well-Known Member

Abstract

Background

Myalgic Encephalopathy/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) is a disease of unknown etiology. We previously reported a pilot case series followed by a small, randomized, placebo-controlled phase II study, suggesting that B-cell depletion using the monoclonal anti-CD20 antibody rituximab can yield clinical benefit in ME/CFS.

Methods

In this single-center, open-label, one-armed phase II study (NCT01156909), 29 patients were included for treatment with rituximab (500 mg/m2) two infusions two weeks apart, followed by maintenance rituximab infusions after 3, 6, 10 and 15 months, and with follow-up for 36 months.

Findings

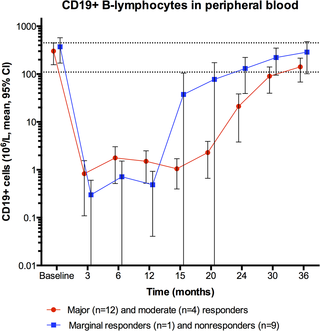

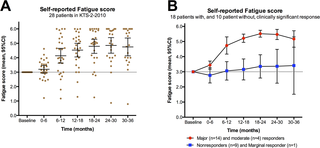

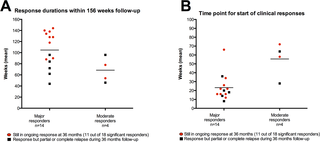

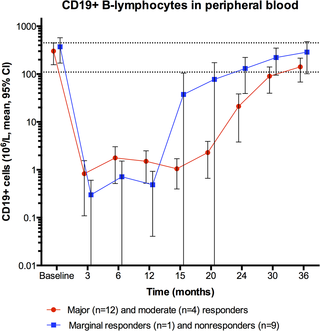

Major or moderate responses, predefined as lasting improvements in self-reported Fatigue score, were detected in 18 out of 29 patients (intention to treat). Clinically significant responses were seen in 18 out of 28 patients (64%) receiving rituximab maintenance treatment. For these 18 patients, the mean response durations within the 156 weeks study period were 105 weeks in 14 major responders, and 69 weeks in four moderate responders. At end of follow-up (36 months), 11 out of 18 responding patients were still in ongoing clinical remission. For major responders, the mean lag time from first rituximab infusion until start of clinical response was 23 weeks (range 8–66). Among the nine patients from the placebo group in the previous randomized study with no significant improvement during 12 months follow-up after saline infusions, six achieved a clinical response before 12 months after rituximab maintenance infusions in the present study. Two patients had an allergic reaction to rituximab and two had an episode of uncomplicated late-onset neutropenia. Eight patients experienced one or more transient symptom flares after rituximab infusions. There was no unexpected toxicity.

Conclusion

In a subgroup of ME/CFS patients, prolonged B-cell depletion with rituximab maintenance infusions was associated with sustained clinical responses. The observed patterns of delayed responses and relapse after B-cell depletion and regeneration, a three times higher disease prevalence in women than in men, and a previously demonstrated increase in B-cell lymphoma risk for elderly ME/CFS patients, suggest that ME/CFS may be a variant of an autoimmune disease.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01156909

Figures

Citation: Fluge Ø, Risa K, Lunde S, Alme K, Rekeland IG, Sapkota D, et al. (2015) B-Lymphocyte Depletion in Myalgic Encephalopathy/ Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. An Open-Label Phase II Study with Rituximab Maintenance Treatment. PLoS ONE 10(7): e0129898. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0129898

Academic Editor: Christina van der Feltz-Cornelis, Tilburg University, NETHERLANDS

Received: February 13, 2015; Accepted: May 14, 2015; Published: July 1, 2015

Copyright: © 2015 Fluge et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited

Data Availability: All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Introduction

Myalgic Encephalopathy/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) is a disease of unknown etiology characterized by severe fatigue and post-exertional malaise, cognitive disturbances, pain, sleep problems, sensory hypersensitivity and several symptoms related to immune and autonomic function. ME/CFS according to Canadian diagnostic criteria [1] comprises approximately 0.1–0.2% of the population [2], and must be distinguished from general fatigue probably affecting ten times as many. A genetic predisposition for ME/CFS has been demonstrated [3].

ME/CFS has profound impact on quality of life for patients and caretakers [4]. The symptom burden is heavy [5], and the disease carries high socioeconomic costs. Patients with severe ME/CFS suffer major functional impairments and often a range of debilitating symptoms. No standard drug treatment has been established, mostly due to lack of knowledge of the underlying disease mechanisms.

We have performed a pilot case series of three patients suggesting clinical activity for B-cell depletion using the monoclonal anti-CD20 antibody rituximab [6]. The case series was followed by a small, randomized, double-blind and placebo-controlled phase II study of 30 patients given either rituximab (two infusions two weeks apart), or placebo, with follow-up for 12 months [7]. The primary endpoint was negative, i.e. there was no difference between the rituximab and placebo groups at 3 months follow-up. There was, however, a significant difference in favor of the rituximab group in the course of Fatigue score during follow-up, most evident between 6–10 months follow-up, and with clinical responses in 2/3 of the patients receiving rituximab. The symptom improvements were delayed, starting 2–8 months after initial and rapid B-cell depletion [7], suggesting that ME/CFS in a subgroup of patients could be a variant of an autoimmune disease involving B-lymphocytes and elimination of long-lived antibodies.

According to protocol for the previous randomized KTS-1-2008 study, patients assigned to the placebo group should be given the opportunity to participate in a new open-label study with rituximab. The protocol for the present study was designed to learn about the therapeutic efficacy of rituximab maintenance treatment, for response rates and response durations. Also, the experiences could form the basis for design of a future randomized, double-blind and placebo-controlled trial. Therefore, we have now performed this open-label phase II study (KTS-2-2010) using rituximab induction (two infusions two weeks apart) followed by rituximab maintenance infusions after 3, 6, 10 and 15 months, and with follow-up for three years.

Materials and Methods

Ethics

The study, including one amendment, was approved by the Regional Ethical Committee in Norway, no 2010/1318-4, and by the National Medicines Agency. All patients gave written informed consent.

Study design and pre-treatment evaluation

This study (KTS-2-2010, EudraCT no. 2010-020481-17, ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01156909) was designed as a single center, open-label phase II trial, one-armed with no randomization, comprising 29 patients (including two pilot patients) with ME/CFS. The main aim was to evaluate the effect of rituximab induction and maintenance treatment on response rates and response durations, and any adverse effects of the treatment, within 36 months follow-up, and to gain experience for the purpose of designing a new multicentre, randomized, double-blind, and placebo-controlled trial. The Protocol for this study, including one amendment, is available as supporting information (S1 Protocol).

The inclusion criteria were: a diagnosis of ME/CFS according to the Fukuda 1994 criteria [8], and age 18–66 years. Exclusion criteria were: fatigue not meeting the diagnostic criteria for ME/CFS, pregnancy or lactation, previous malignant disease (except basal cell carcinoma in skin or cervical dysplasia), previous severe immune system disease (except autoimmune diseases such as e.g. thyroiditis or diabetes type I), previous long-term systemic immunosuppressive treatment (such as azathioprine, cyclosporine, mycophenolate mofetil, except steroid courses for e.g. obstructive lung disease), endogenous depression, lack of ability to adhere to protocol, known multi-allergy with clinical risk from rituximab infusions, reduced kidney function (serum creatinine > 1.5x upper normal value), reduced liver function (serum bilirubin or liver transaminases > 1.5x upper normal), known HIV infection, or evidence of ongoing active and relevant infection.

The pre-treatment evaluation included standard laboratory tests (hematology, liver function, renal function), HCG to exclude pregnancy in fertile women, endocrine assessment (thyroid, adrenal, prolactin), serology for virus (EBV, CMV, HSV, VZV, Enterovirus, Parvovirus B19, adenovirus), immunophenotyping of peripheral blood lymphocyte subsets, common autoantibodies, and serum immunoglobulins (IgG, IgM, IgA) with IgG subclasses. MRI of the brain was previously performed in all patients. Further diagnostic tests were performed if the pre-treatment evaluation including clinical examination revealed any relevant abnormality that could explain the severe fatigue experienced by the patients.

Self-reported ME/CFS symptom scoring

Before intervention, the patients assessed their ME/CFS disease status the last three months and recorded their symptoms according to a scale (1–10; 1: no symptom; 5: moderate symptom; 10: very severe symptom) (S1 Fig).

During follow-up, every second week the patients recorded the overall change in each symptom during the preceding two weeks, always compared to baseline (S2 Fig). The scale (0–6) for the follow-up form was: 0: Major worsening; 1: Moderate worsening; 2: Slight worsening; 3: No change from baseline; 4: Slight improvement; 5: Moderate improvement; 6: Major improvement. These forms for self-reported symptoms were similar to those used in the previous randomized phase II study [7].

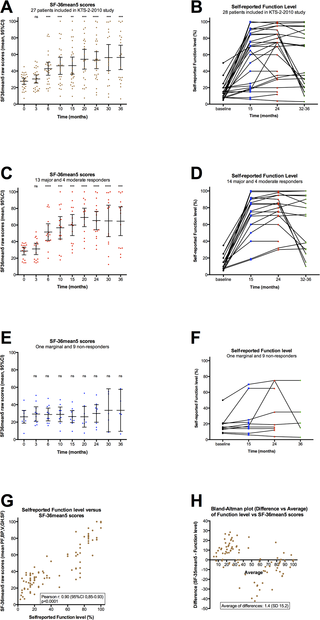

The self-reported symptom changes recorded every second week and always compared to baseline are relative, i.e. an improvement interpreted as moderate or major will be different in a patient with severe ME/CFS who is mostly bedridden, and a patient with mild ME/CFS who is able to perform some level of activity. Therefore, the patients also registered their “Function level” on a scale 0–100%, according to a form with examples in which 100% denoted a completely healthy state as before acquiring ME/CFS (S3 Fig). According to this form, patients with very severe ME/CFS will report a Function level < 5%, patients with severe ME/CFS will report Function level 5–10% (mostly bedridden), patients with moderate ME/CFS 10–15% (mainly housebound), and patients with milder degree of ME/CFS a Function level in the range of 20–50%. The patients estimated self-reported Function level at baseline, at 15, 24 and 36 months. This recording of Function level was not predefined in the protocol.

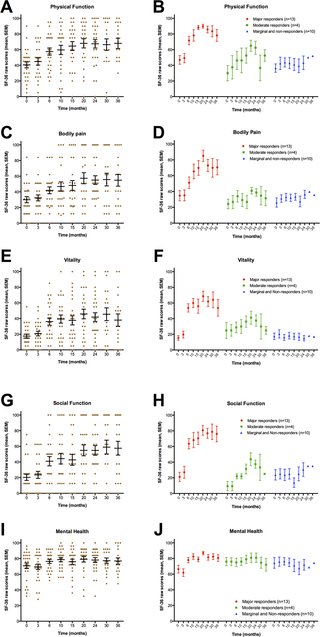

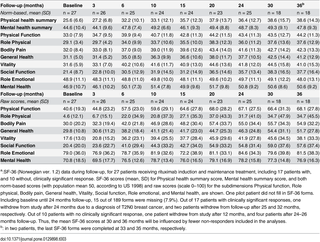

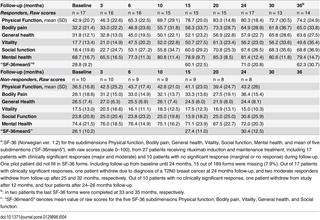

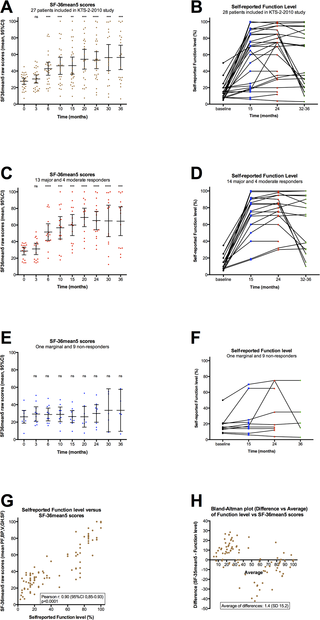

At baseline, and at 3, 6, 10, 15, 20, 24, 30 and 36 months, the patients recorded the SF-36 Norwegian version 1.2 short form scheme, which is a general health-related quality of life questionnaire assessing Physical health summary score, Mental health summary score, and eight subdimensions (Physical function, Role-physical, Bodily pain, Vitality, General health, Social function, Role-emotional, and Mental health) [9,10]. Both norm-based scores based on population mean values of approximately 50, according to population norm US 1998, and raw scores (scale 0–100) were calculated.

Endpoints

The primary endpoint was effect on self-reported ME/CFS symptoms during follow-up. A clinical response period was defined as Fatigue score ≥ 4.5 for at least six consecutive weeks (i.e. for at least three consecutive two-week recordings), which must also include at least one recording of Fatigue score > 5.0 during the response period, but not predefined to any specific time interval during three years follow-up. Single response periods, and the sum of such periods were recorded as response durations during follow-up.

Secondary endpoints were effects on the ME/CFS symptoms, at 3, 6, 10, 15, 20, 24, 30 and 36 months assessed by the SF-36 questionnaire, the longest consecutive response period (continuous mean Fatigue score ≥ 4.5), the fraction of included patients still in response at end of study (36 months), and toxicity during follow-up.

Treatment schedule and follow-up

The patients were given rituximab infusions in the outpatient clinic at Department of Oncology, Haukeland University Hospital. The induction treatment, rituximab 500 mg/m2 (maximum 1000 mg), diluted in saline to a concentration of 2 mg/ml, was administered twice with two weeks interval, with nurse surveillance and according to local guidelines. The patients then received rituximab maintenance infusions, 500 mg/m2 (maximum 1000 mg) at 3, 6, 10 and 15 months follow-up. All patients were given oral cetirizine 10 mg, paracetamol 1 g, and dexamethasone 8 mg prior to infusion. The two pilot patients received only one rituximab induction infusion, with the sixth (last) infusion at 18 and 19 months (instead of 15 months) respectively.

According to protocol, the planned 10 and 15 months infusions could be omitted if there were no signs of clinical response at the 10-months visit.

The present open-label phase II study also had exploratory elements, aiming to gain knowledge on dose-response relationships for proper design of a later randomized phase III study. Therefore, by December 2011 an amendment was submitted to and approved by The Regional Ethical Committee; for patients with slow and gradual improvement after 12 months follow-up including five rituximab infusions, up to six additional rituximab infusions could be given with at least two months intervals. No other intervention should be given during follow-up. After infusions, the patients attended the outpatient clinic at 20, 24, 30 and 36 months, for assessment of the clinical course of their disease, including delivery of self-reported symptom forms. Most of the patients including those still in ongoing remission at the end of follow-up, have been assessed at regular intervals even after the study period.

Response definitions and statistical analyses

Similar to the previous randomized phase II study [7], the self-reported symptom changes recorded every second week and always compared to baseline (S2 Fig scale 0–6), were used to calculate symptom scores during follow-up. The Fatigue score was calculated every second week as the mean of the four symptoms: Fatigue, Post-exertional malaise, Need for rest, Daily functioning. The Pain score was calculated as the mean of the two dominating pain symptoms (if pre-treatment level ≥ 4, among Muscle pain, Joint pain, Headache, Cutaneous pain). The Cognitive score was the mean of the three symptoms: Concentration ability, Memory disturbance, Mental tiredness. The Fatigue score, Pain score, and Cognitive score were plotted every second week, for each patient in separate diagrams.

The main response was defined from the Fatigue score. For overall response rate (ORR) a clinical response was defined as a Fatigue score ≥ 4.5 for at least six consecutive weeks, which must include at least one recording of Fatigue score > 5.0 during the response period. For each patient, the mean of Fatigue scores for the time intervals 0–6, 6–12, 12–18, 18–24, 24–30 and 30–36 months were calculated. For the 28 patients receiving rituximab induction and maintenance treatment, the Fatigue scores for the time intervals (mean with 95% confidence intervals) were then plotted.

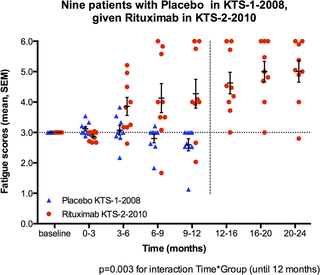

For the nine patients in this study who had been randomized to the placebo group in the previous phase II study [7], mean Fatigue scores for the time intervals 0–3, 3–6, 6–9 and 9–12 months in the present study with rituximab maintenance treatment were plotted together with mean Fatigue scores for the same time intervals from their 12 months follow-up in the placebo group in the previous study (in other words, these nine patients were their own “historic controls”). General linear model (GLM) for repeated measures was used to compare the differences in distribution of Fatigue scores for the consecutive 3-months time intervals during 12 months follow-up, between the same nine patients when participating in the present rituximab maintenance (KTS-2-2010) study and when participating in the placebo group in KTS-1-2008 study. Mean Fatigue scores for four time intervals were included in the analyses, and Greenhouse-Geisser adjustments were made due to significant Mauchly’s tests for sphericity. The main effect for the interaction between time and group (i.e. rituximab maintenance versus “historical” placebo) was assessed.

SF-36 data from baseline, and from 3, 6, 10, 15, 20, 24, 30, and 36 months follow-up were analyzed using a SPSS syntax file, with both raw scores (scale 0–100) and norm-based scores in which the population mean score is approximately 50 (according to US 1998). For analysis of correlation between “SF-36mean5” and self-reported Function level, SF-36 raw scores were used. The statistical analyses were performed using SPSS for Macintosh, ver. 22, and Graphpad Prism ver. 6. Punching of data was performed by ØF and by the staff at the office for cancer research at the Dept. of Oncology. Analyses were performed by ØF and OM. Accuracy of data punching and analyses were checked by IGR and KS.

Patient characteristics

The Consort flow diagram for the KTS-2-2010 study is shown in Fig 1. Between September 2010 and February 2011, 27 patients were included. In addition, two pilot patients started maintenance rituximab treatment from July 2009. End of follow-up was in February 2014. The patients were partly recruited through referrals from the Dept. of Neurology, Haukeland University Hospital, and partly through primary care physicians.

Fig 1. Consort 2010 Flow Diagram for the KTS-2-2010 study.

Consort Flow Diagram for the KTS-2-2010 study, with enrollment, allocation to induction and maintenance rituximab treatment, and follow-up showing number of patients who withdrew from study before 36 months.

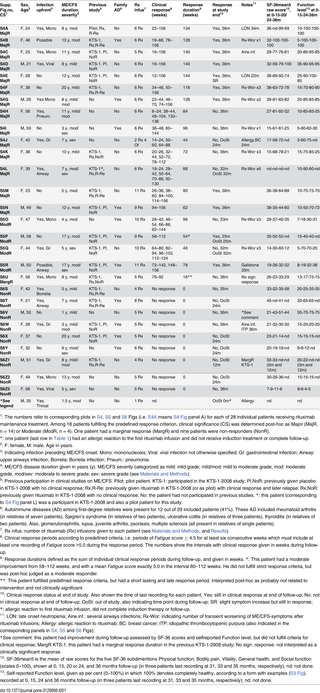

Among the 29 patients, 20 (69%) were women. The mean age was 40 years (range 21–59 years). The mean duration of ME/CFS was 9 years (range 1–20 years). Out of 29 included patients, 13 had moderate severity (mainly housebound), four had moderate/severe, and three had severe (mainly bedridden) ME/CFS. Four had mild/moderate and five patients mild ME/CFS [11] (Table 1). During the preceding year before inclusion, 17 patients reported a stable ME/CFS disease, five had experienced worsening of symptoms, and seven had relapse after previous rituximab-associated responses. Infection before ME/CFS onset had been evident in 17 patients (59%), in two patients (7%) a relation to preceding infection was possible, and there was no clear history of infection upfront in 10 (34%).

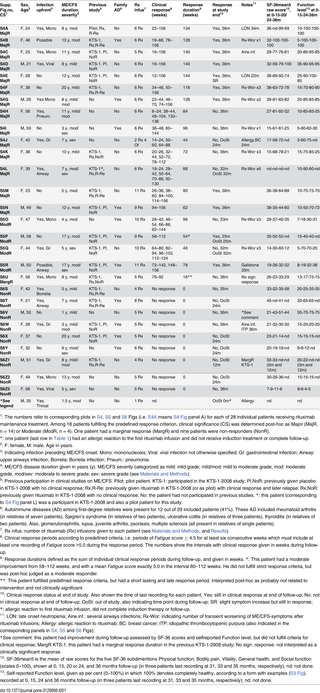

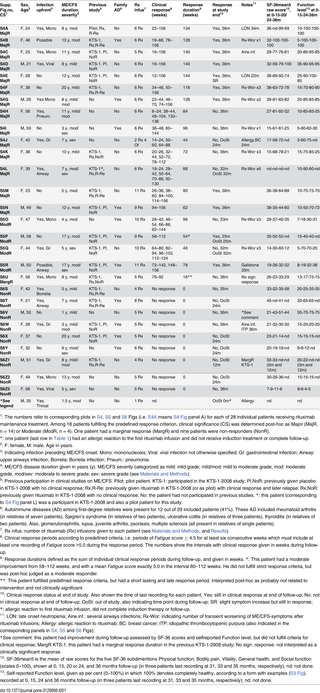

Table 1. ME/CFS disease characteristics and selected response data, for 29 patients included in the study.

In three patients (10%) an autoimmune disease had previously been diagnosed (thyroiditis, psoriasis, juvenile arthritis). In 12 patients (41%) an autoimmune disease had been diagnosed among first-degree relatives (Table 1). In addition, three patients (10%) reported a diagnosis of ME/CFS, and two patients (7%) a diagnosis of fibromyalgia, among their first-degree relatives.

Nine patients from the rituximab group in the KTS-1-2008 study, and one pilot patient who had received a single rituximab infusion previously, were included (Table 1, Fig 1). Among these ten patients, two had no response to rituximab during the previous KTS-1-2008 study, one had a marginal response, and seven had clinical response but subsequent relapse of ME/CFS before entering the present KTS-2-2010 study. Nine patients from the placebo group in the randomized KTS-1-2008 study were included in the present study (Table 1, Fig 1). Thus, out of 29 included, 10 patients (34%) had not participated in our previous clinical studies for ME/CFS.

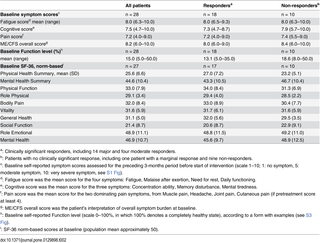

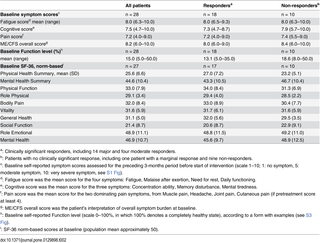

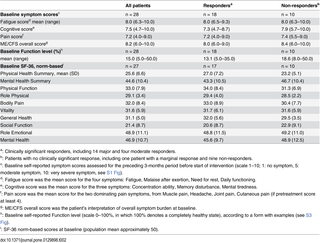

The baseline symptom scores derived from the baseline forms (scale 1–10, S1 Fig), self-reported baseline Function level (scale 0–100%, form with examples in S3 Fig), and baseline SF-36 norm-based scores, are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Baseline self-reported symptom scores, baseline Function level, and baseline norm-based SF-36 scores, for 28 patients receiving rituximab induction and maintenance treatment.

Background

Myalgic Encephalopathy/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) is a disease of unknown etiology. We previously reported a pilot case series followed by a small, randomized, placebo-controlled phase II study, suggesting that B-cell depletion using the monoclonal anti-CD20 antibody rituximab can yield clinical benefit in ME/CFS.

Methods

In this single-center, open-label, one-armed phase II study (NCT01156909), 29 patients were included for treatment with rituximab (500 mg/m2) two infusions two weeks apart, followed by maintenance rituximab infusions after 3, 6, 10 and 15 months, and with follow-up for 36 months.

Findings

Major or moderate responses, predefined as lasting improvements in self-reported Fatigue score, were detected in 18 out of 29 patients (intention to treat). Clinically significant responses were seen in 18 out of 28 patients (64%) receiving rituximab maintenance treatment. For these 18 patients, the mean response durations within the 156 weeks study period were 105 weeks in 14 major responders, and 69 weeks in four moderate responders. At end of follow-up (36 months), 11 out of 18 responding patients were still in ongoing clinical remission. For major responders, the mean lag time from first rituximab infusion until start of clinical response was 23 weeks (range 8–66). Among the nine patients from the placebo group in the previous randomized study with no significant improvement during 12 months follow-up after saline infusions, six achieved a clinical response before 12 months after rituximab maintenance infusions in the present study. Two patients had an allergic reaction to rituximab and two had an episode of uncomplicated late-onset neutropenia. Eight patients experienced one or more transient symptom flares after rituximab infusions. There was no unexpected toxicity.

Conclusion

In a subgroup of ME/CFS patients, prolonged B-cell depletion with rituximab maintenance infusions was associated with sustained clinical responses. The observed patterns of delayed responses and relapse after B-cell depletion and regeneration, a three times higher disease prevalence in women than in men, and a previously demonstrated increase in B-cell lymphoma risk for elderly ME/CFS patients, suggest that ME/CFS may be a variant of an autoimmune disease.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01156909

Figures

Citation: Fluge Ø, Risa K, Lunde S, Alme K, Rekeland IG, Sapkota D, et al. (2015) B-Lymphocyte Depletion in Myalgic Encephalopathy/ Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. An Open-Label Phase II Study with Rituximab Maintenance Treatment. PLoS ONE 10(7): e0129898. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0129898

Academic Editor: Christina van der Feltz-Cornelis, Tilburg University, NETHERLANDS

Received: February 13, 2015; Accepted: May 14, 2015; Published: July 1, 2015

Copyright: © 2015 Fluge et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited

Data Availability: All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Introduction

Myalgic Encephalopathy/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) is a disease of unknown etiology characterized by severe fatigue and post-exertional malaise, cognitive disturbances, pain, sleep problems, sensory hypersensitivity and several symptoms related to immune and autonomic function. ME/CFS according to Canadian diagnostic criteria [1] comprises approximately 0.1–0.2% of the population [2], and must be distinguished from general fatigue probably affecting ten times as many. A genetic predisposition for ME/CFS has been demonstrated [3].

ME/CFS has profound impact on quality of life for patients and caretakers [4]. The symptom burden is heavy [5], and the disease carries high socioeconomic costs. Patients with severe ME/CFS suffer major functional impairments and often a range of debilitating symptoms. No standard drug treatment has been established, mostly due to lack of knowledge of the underlying disease mechanisms.

We have performed a pilot case series of three patients suggesting clinical activity for B-cell depletion using the monoclonal anti-CD20 antibody rituximab [6]. The case series was followed by a small, randomized, double-blind and placebo-controlled phase II study of 30 patients given either rituximab (two infusions two weeks apart), or placebo, with follow-up for 12 months [7]. The primary endpoint was negative, i.e. there was no difference between the rituximab and placebo groups at 3 months follow-up. There was, however, a significant difference in favor of the rituximab group in the course of Fatigue score during follow-up, most evident between 6–10 months follow-up, and with clinical responses in 2/3 of the patients receiving rituximab. The symptom improvements were delayed, starting 2–8 months after initial and rapid B-cell depletion [7], suggesting that ME/CFS in a subgroup of patients could be a variant of an autoimmune disease involving B-lymphocytes and elimination of long-lived antibodies.

According to protocol for the previous randomized KTS-1-2008 study, patients assigned to the placebo group should be given the opportunity to participate in a new open-label study with rituximab. The protocol for the present study was designed to learn about the therapeutic efficacy of rituximab maintenance treatment, for response rates and response durations. Also, the experiences could form the basis for design of a future randomized, double-blind and placebo-controlled trial. Therefore, we have now performed this open-label phase II study (KTS-2-2010) using rituximab induction (two infusions two weeks apart) followed by rituximab maintenance infusions after 3, 6, 10 and 15 months, and with follow-up for three years.

Materials and Methods

Ethics

The study, including one amendment, was approved by the Regional Ethical Committee in Norway, no 2010/1318-4, and by the National Medicines Agency. All patients gave written informed consent.

Study design and pre-treatment evaluation

This study (KTS-2-2010, EudraCT no. 2010-020481-17, ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01156909) was designed as a single center, open-label phase II trial, one-armed with no randomization, comprising 29 patients (including two pilot patients) with ME/CFS. The main aim was to evaluate the effect of rituximab induction and maintenance treatment on response rates and response durations, and any adverse effects of the treatment, within 36 months follow-up, and to gain experience for the purpose of designing a new multicentre, randomized, double-blind, and placebo-controlled trial. The Protocol for this study, including one amendment, is available as supporting information (S1 Protocol).

The inclusion criteria were: a diagnosis of ME/CFS according to the Fukuda 1994 criteria [8], and age 18–66 years. Exclusion criteria were: fatigue not meeting the diagnostic criteria for ME/CFS, pregnancy or lactation, previous malignant disease (except basal cell carcinoma in skin or cervical dysplasia), previous severe immune system disease (except autoimmune diseases such as e.g. thyroiditis or diabetes type I), previous long-term systemic immunosuppressive treatment (such as azathioprine, cyclosporine, mycophenolate mofetil, except steroid courses for e.g. obstructive lung disease), endogenous depression, lack of ability to adhere to protocol, known multi-allergy with clinical risk from rituximab infusions, reduced kidney function (serum creatinine > 1.5x upper normal value), reduced liver function (serum bilirubin or liver transaminases > 1.5x upper normal), known HIV infection, or evidence of ongoing active and relevant infection.

The pre-treatment evaluation included standard laboratory tests (hematology, liver function, renal function), HCG to exclude pregnancy in fertile women, endocrine assessment (thyroid, adrenal, prolactin), serology for virus (EBV, CMV, HSV, VZV, Enterovirus, Parvovirus B19, adenovirus), immunophenotyping of peripheral blood lymphocyte subsets, common autoantibodies, and serum immunoglobulins (IgG, IgM, IgA) with IgG subclasses. MRI of the brain was previously performed in all patients. Further diagnostic tests were performed if the pre-treatment evaluation including clinical examination revealed any relevant abnormality that could explain the severe fatigue experienced by the patients.

Self-reported ME/CFS symptom scoring

Before intervention, the patients assessed their ME/CFS disease status the last three months and recorded their symptoms according to a scale (1–10; 1: no symptom; 5: moderate symptom; 10: very severe symptom) (S1 Fig).

During follow-up, every second week the patients recorded the overall change in each symptom during the preceding two weeks, always compared to baseline (S2 Fig). The scale (0–6) for the follow-up form was: 0: Major worsening; 1: Moderate worsening; 2: Slight worsening; 3: No change from baseline; 4: Slight improvement; 5: Moderate improvement; 6: Major improvement. These forms for self-reported symptoms were similar to those used in the previous randomized phase II study [7].

The self-reported symptom changes recorded every second week and always compared to baseline are relative, i.e. an improvement interpreted as moderate or major will be different in a patient with severe ME/CFS who is mostly bedridden, and a patient with mild ME/CFS who is able to perform some level of activity. Therefore, the patients also registered their “Function level” on a scale 0–100%, according to a form with examples in which 100% denoted a completely healthy state as before acquiring ME/CFS (S3 Fig). According to this form, patients with very severe ME/CFS will report a Function level < 5%, patients with severe ME/CFS will report Function level 5–10% (mostly bedridden), patients with moderate ME/CFS 10–15% (mainly housebound), and patients with milder degree of ME/CFS a Function level in the range of 20–50%. The patients estimated self-reported Function level at baseline, at 15, 24 and 36 months. This recording of Function level was not predefined in the protocol.

At baseline, and at 3, 6, 10, 15, 20, 24, 30 and 36 months, the patients recorded the SF-36 Norwegian version 1.2 short form scheme, which is a general health-related quality of life questionnaire assessing Physical health summary score, Mental health summary score, and eight subdimensions (Physical function, Role-physical, Bodily pain, Vitality, General health, Social function, Role-emotional, and Mental health) [9,10]. Both norm-based scores based on population mean values of approximately 50, according to population norm US 1998, and raw scores (scale 0–100) were calculated.

Endpoints

The primary endpoint was effect on self-reported ME/CFS symptoms during follow-up. A clinical response period was defined as Fatigue score ≥ 4.5 for at least six consecutive weeks (i.e. for at least three consecutive two-week recordings), which must also include at least one recording of Fatigue score > 5.0 during the response period, but not predefined to any specific time interval during three years follow-up. Single response periods, and the sum of such periods were recorded as response durations during follow-up.

Secondary endpoints were effects on the ME/CFS symptoms, at 3, 6, 10, 15, 20, 24, 30 and 36 months assessed by the SF-36 questionnaire, the longest consecutive response period (continuous mean Fatigue score ≥ 4.5), the fraction of included patients still in response at end of study (36 months), and toxicity during follow-up.

Treatment schedule and follow-up

The patients were given rituximab infusions in the outpatient clinic at Department of Oncology, Haukeland University Hospital. The induction treatment, rituximab 500 mg/m2 (maximum 1000 mg), diluted in saline to a concentration of 2 mg/ml, was administered twice with two weeks interval, with nurse surveillance and according to local guidelines. The patients then received rituximab maintenance infusions, 500 mg/m2 (maximum 1000 mg) at 3, 6, 10 and 15 months follow-up. All patients were given oral cetirizine 10 mg, paracetamol 1 g, and dexamethasone 8 mg prior to infusion. The two pilot patients received only one rituximab induction infusion, with the sixth (last) infusion at 18 and 19 months (instead of 15 months) respectively.

According to protocol, the planned 10 and 15 months infusions could be omitted if there were no signs of clinical response at the 10-months visit.

The present open-label phase II study also had exploratory elements, aiming to gain knowledge on dose-response relationships for proper design of a later randomized phase III study. Therefore, by December 2011 an amendment was submitted to and approved by The Regional Ethical Committee; for patients with slow and gradual improvement after 12 months follow-up including five rituximab infusions, up to six additional rituximab infusions could be given with at least two months intervals. No other intervention should be given during follow-up. After infusions, the patients attended the outpatient clinic at 20, 24, 30 and 36 months, for assessment of the clinical course of their disease, including delivery of self-reported symptom forms. Most of the patients including those still in ongoing remission at the end of follow-up, have been assessed at regular intervals even after the study period.

Response definitions and statistical analyses

Similar to the previous randomized phase II study [7], the self-reported symptom changes recorded every second week and always compared to baseline (S2 Fig scale 0–6), were used to calculate symptom scores during follow-up. The Fatigue score was calculated every second week as the mean of the four symptoms: Fatigue, Post-exertional malaise, Need for rest, Daily functioning. The Pain score was calculated as the mean of the two dominating pain symptoms (if pre-treatment level ≥ 4, among Muscle pain, Joint pain, Headache, Cutaneous pain). The Cognitive score was the mean of the three symptoms: Concentration ability, Memory disturbance, Mental tiredness. The Fatigue score, Pain score, and Cognitive score were plotted every second week, for each patient in separate diagrams.

The main response was defined from the Fatigue score. For overall response rate (ORR) a clinical response was defined as a Fatigue score ≥ 4.5 for at least six consecutive weeks, which must include at least one recording of Fatigue score > 5.0 during the response period. For each patient, the mean of Fatigue scores for the time intervals 0–6, 6–12, 12–18, 18–24, 24–30 and 30–36 months were calculated. For the 28 patients receiving rituximab induction and maintenance treatment, the Fatigue scores for the time intervals (mean with 95% confidence intervals) were then plotted.

For the nine patients in this study who had been randomized to the placebo group in the previous phase II study [7], mean Fatigue scores for the time intervals 0–3, 3–6, 6–9 and 9–12 months in the present study with rituximab maintenance treatment were plotted together with mean Fatigue scores for the same time intervals from their 12 months follow-up in the placebo group in the previous study (in other words, these nine patients were their own “historic controls”). General linear model (GLM) for repeated measures was used to compare the differences in distribution of Fatigue scores for the consecutive 3-months time intervals during 12 months follow-up, between the same nine patients when participating in the present rituximab maintenance (KTS-2-2010) study and when participating in the placebo group in KTS-1-2008 study. Mean Fatigue scores for four time intervals were included in the analyses, and Greenhouse-Geisser adjustments were made due to significant Mauchly’s tests for sphericity. The main effect for the interaction between time and group (i.e. rituximab maintenance versus “historical” placebo) was assessed.

SF-36 data from baseline, and from 3, 6, 10, 15, 20, 24, 30, and 36 months follow-up were analyzed using a SPSS syntax file, with both raw scores (scale 0–100) and norm-based scores in which the population mean score is approximately 50 (according to US 1998). For analysis of correlation between “SF-36mean5” and self-reported Function level, SF-36 raw scores were used. The statistical analyses were performed using SPSS for Macintosh, ver. 22, and Graphpad Prism ver. 6. Punching of data was performed by ØF and by the staff at the office for cancer research at the Dept. of Oncology. Analyses were performed by ØF and OM. Accuracy of data punching and analyses were checked by IGR and KS.

Patient characteristics

The Consort flow diagram for the KTS-2-2010 study is shown in Fig 1. Between September 2010 and February 2011, 27 patients were included. In addition, two pilot patients started maintenance rituximab treatment from July 2009. End of follow-up was in February 2014. The patients were partly recruited through referrals from the Dept. of Neurology, Haukeland University Hospital, and partly through primary care physicians.

Fig 1. Consort 2010 Flow Diagram for the KTS-2-2010 study.

Consort Flow Diagram for the KTS-2-2010 study, with enrollment, allocation to induction and maintenance rituximab treatment, and follow-up showing number of patients who withdrew from study before 36 months.

Among the 29 patients, 20 (69%) were women. The mean age was 40 years (range 21–59 years). The mean duration of ME/CFS was 9 years (range 1–20 years). Out of 29 included patients, 13 had moderate severity (mainly housebound), four had moderate/severe, and three had severe (mainly bedridden) ME/CFS. Four had mild/moderate and five patients mild ME/CFS [11] (Table 1). During the preceding year before inclusion, 17 patients reported a stable ME/CFS disease, five had experienced worsening of symptoms, and seven had relapse after previous rituximab-associated responses. Infection before ME/CFS onset had been evident in 17 patients (59%), in two patients (7%) a relation to preceding infection was possible, and there was no clear history of infection upfront in 10 (34%).

Table 1. ME/CFS disease characteristics and selected response data, for 29 patients included in the study.

In three patients (10%) an autoimmune disease had previously been diagnosed (thyroiditis, psoriasis, juvenile arthritis). In 12 patients (41%) an autoimmune disease had been diagnosed among first-degree relatives (Table 1). In addition, three patients (10%) reported a diagnosis of ME/CFS, and two patients (7%) a diagnosis of fibromyalgia, among their first-degree relatives.

Nine patients from the rituximab group in the KTS-1-2008 study, and one pilot patient who had received a single rituximab infusion previously, were included (Table 1, Fig 1). Among these ten patients, two had no response to rituximab during the previous KTS-1-2008 study, one had a marginal response, and seven had clinical response but subsequent relapse of ME/CFS before entering the present KTS-2-2010 study. Nine patients from the placebo group in the randomized KTS-1-2008 study were included in the present study (Table 1, Fig 1). Thus, out of 29 included, 10 patients (34%) had not participated in our previous clinical studies for ME/CFS.

The baseline symptom scores derived from the baseline forms (scale 1–10, S1 Fig), self-reported baseline Function level (scale 0–100%, form with examples in S3 Fig), and baseline SF-36 norm-based scores, are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Baseline self-reported symptom scores, baseline Function level, and baseline norm-based SF-36 scores, for 28 patients receiving rituximab induction and maintenance treatment.