Remy

Administrator

Here is an overview of HRV by Ben Greenfield:

Plus a link to the app and monitor I have:

http://sweetwaterhrv.com/index.shtml

Ben Greenfield has several episodes of his podcasts devoted to HRV. Just be careful because he is like the used car salesman of Health and Wellness...The origin of your heartbeat is located in what is called a “node” of your heart, in this case, something called the sino-atrial (SA) node. In your SA node, cells in your heart continuously generate an electrical impulse that spreads throughout your entire heart muscle and causes a contraction (Levy).

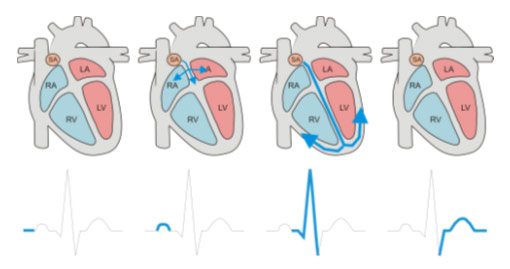

Generally, your SA node will generate a certain number of these electrical impulses per minute, which is how many times your heart will beat per minute. Below is a graphic of how your SA node initiates the electrical impulse that causes a contraction to propagate from through the Right Atrium (RA) and Right Ventricle (RV) to the Left Atrium (LA) and Left Ventricle (LV) of your heart.

So where does HRV fit into this equation?

Here’s how: Your SA node activity, heart rate and rhythm are largely under the control of your autonomic nervous system, which is split into two branches, your “rest and digest” parasympathetic nervous system and your “fight and flight” sympathetic nervous system.

Your parasympathetic nervous system (“rest-and-digest”) influences heart rate via the release of a compound called acetylcholine by your vagus nerve, which can inhibit activation of SA node activity and decrease heart rate variability.

In contrast, your sympathetic nervous system (“fight-and-flight”) influences heart rate by release of epinephrine and norepinephrine, and generally increases activation of the SA node and increases heart rate variability.

If you’re well rested, haven’t been training excessively and aren’t in a state of over-reaching, your parasympathetic nervous system interacts cooperatively with your sympathetic nervous system to produce responses in your heart rate variability to respiration, temperature, blood pressure, stress, etc (Perini). And as a result, you tend to have really nice, consistent and high HRV values, which are typically measured on a 0-100 scale. The higher the HRV, the better your score.

But if you’re not well rested (over-reached or under-recovered), the normally healthy beat-to-beat variation in your heart rhythm begins to diminish. While normal variability would indicate sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system balance, and a proper regulation of your heartbeat by your nervous system, it can certainly be a serious issue if you see abnormal variability – such as consistently low HRV values (e.g. below 60) or HRV values that tend to jump around a lot from day-to-day (70 one day, 90 another day, 60 the next day, etc.).

In other words, these issues would indicate that the delicate see-saw balance of your sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system no longer works.

In a strength or speed athlete, or someone who is overdoing things from an intensity standpoint, you typically see more sympathetic nervous system overtraining, and a highly variable HRV (a heart rate variability number that bounces around from day to day).

In contrast, in endurance athletes or people who are overdoing things with too much long, slow, chronic cardio, you typically see more parasympathetic nervous system overtraining, and a consistently low HRV value (Mourot).

In my own case, as I’ve neared the finish of my build to any big triathlon, I’ve noticed consistently low HRV scores – indicating I am nearing an overreached status and my parasympathetic, aerobically trained nervous system is getting “overcooked”. And in the off-season, when I do more weight training and high intensity cardio or sprint sports, I’ve noticed more of the highly variable HRV issues. In either case case, recovery of a taxed nervous system can be fixed by training less, decreasing volume, or decreasing intensity – supercompensation, right?

But wait – we’re not done yet! HRV can get even more complex than simply a 0-100 number.

For example, when using an HRV tracking tool, you can also track your nervous system’s LF (low frequency) and HF (high frequency) power levels. This is important to track for a couple of reasons:

-Higher power in LF and HF represents greater flexibility and a very robust nervous system.

-Sedentary people have numbers in the low 100’s (100-300) or even lower, fit and active people are around 900 – 1800 and so on as fitness and health improve.

Tracking LF and HF together can really illustrate the balance in your nervous system. In general, you want the two to be relatively close. When they are not, it may indicate that the body is in deeply rested state with too much parasympathetic nervous system activation (HF is high) or in a stressed state with too much sympathetic nervous system activation (LF is high). Confused as I was when I first learned about this stuff?

Then listen to this podcast interview I did with a heart rate variability testing company called Sweetbeat. It will really elucidate this whole frequency thing for you.

So how the heck do you test HRV?

When it comes to self quantification, there are a ton of devices out there for tracking HRV (and hours of sleep, heart rate, pulse oximetry, perspiration, respiration, calories burnt, steps taken, distance traveled and more).

Plus a link to the app and monitor I have:

http://sweetwaterhrv.com/index.shtml