I’ve had Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (ME) for 32 years. I was 24 when I first became ill with it after contracting a virus of some sort while teaching high school in East Salinas, California – just east of Monterey Bay.

The students I taught were the children of immigrants; hard working field workers of the Salinas Valley. This was Steinbeck country! Many of Steinbeck’s stories had been about the Salinas Valley. My students’ stories with their social injustices and economic hardships could have been taken straight out of one of Steinbeck’s novels.

Carnaval! Terri and her blond sister are in the middle of the picture.[/caption]In 1984 the school where I began teaching was surrounded by the fields our students sometimes worked in. I taught College Prep English and English as a Second Language to varying grades and levels of knowledge. My immigrant students were eager to learn the language of their new country, and I was eager to teach them. I wanted to unlock the barrier of language for them so they could rise to the successes they aspired to be. I had a passion for what I did, and it seemed I received so much more from the kids than what I gave to them. I was convinced this was what I was put on this earth to do. It was my purpose.

I understood the barriers of language because as a child I had been in a similar situation. I was raised in an assortment of countries in Latin America since the age of 5. When I first moved to Brazil, I didn’t understand why the cartoon characters on TV were speaking in a different language. My 5 year old brain figured it must have something to do with the electricity since the electricity was Brazilian and not American. Therefore, when the tiny black and white portable television set with rabbit ears was plugged in, it must have magically converted everyone’s words into Portuguese. It made sense to me at the time. I think we all have a need to make sense of the world no matter what age we are.

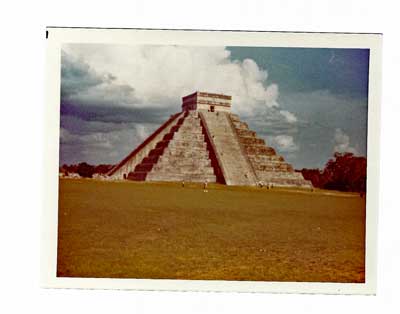

My parents were educators and wanted the experience of travelling while working in American schools abroad. And travel we did. We travelled to Iguacu Falls where we boated (I swear) right up to the edge of the roaring falls; we traversed and hiked the magical and mystical trails through the Machu Picchu ruins; we experienced the cosmopolitan city of Buenos Aires and the pampas of Argentina where we ate the best steaks of our lives; we travelled to spectacular Lake Titicaca which made us kids laugh each and every time we uttered the name; and we travelled into the high mountainous beauty and starkness of Bolivia.

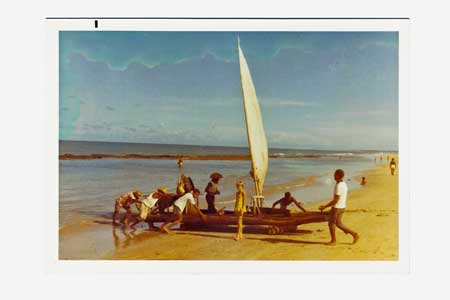

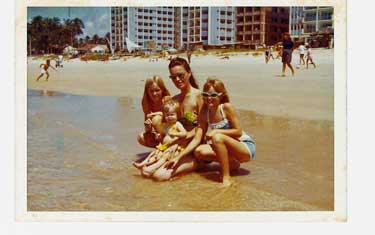

As a child, I was in perpetual motion climbing coconut and mango trees (where I found out I was extremely allergic to mangoes), playing in the streets with the local children, swimming at the beautiful beaches, exploring the surrounding culture by participating in the local holidays and traditions, and eating the delicious cuisine du jour! There was always something exciting to see, hear, do, or try. It was a treat to the senses, with the exception of some of the smells at times due to the tropical humidity. The piles of garbage or rotting fruit along the side of the road in Brazil were no treat, and I’d breathe through my mouth in an effort to avoid the offensiveness.

When we traveled by car to some of these places, the humidity was so prevalent that our undergarments would not dry overnight after our mother’s tireless washing efforts in the hotel sink. Much to my older sister’s and my consternation, those moist garments were then hung out the car windows to dry in the warm air as we sped by 8 foot tall ant hills that dwarfed my father’s 6 foot, six inch frame.

With the noted exception of our flapping undergarments, which looked like banners of surrender streaming from all of our car windows as we travelled throughout Latin America, this was the idyllic backdrop to my childhood. I soon learned Portuguese, and in subsequent years, Spanish. Not many can say they started kindergarten in Rio de Janeiro and danced at Carnival, all in the same year!

There were many other places we experienced. I felt like I was a gypsy; although I had been born in the U.S., I was a child of the world.

My father occupied various jobs in administration in private American schools. Those positions ranged from vice-principal, principal, to Head Master /Director. My mother sometimes taught and other times stayed home with my sisters and I. We lived outside the US in four different cities: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; Recife, Brazil; Lima, Peru, and, finally, Torreon, Mexico, before returning home to attend university because my grandfather was ill and dying.

My parents, years later when they first retired, moved out of the US and into the bubbling cauldron that was Medellin, Columbia during the time of Pablo Escobar’s infamous reign, but that’s a whole other story! Though Medellin was not a very safe place to visit, especially as an American, you’d better believe I travelled to visit them. I happily experienced the wonders of beautiful Columbia. I also witnessed the sad and violent dynamics of the drug cartels and political turbulence that had been inflicted upon their beloved country.

Our travels exposed me to life in third world countries which was both beautiful and sobering at the same time. We slept in mosquito netting in Brazil, which might have sounded fun from the perspective of a child except there was no air conditioning. Instead, there was plenty of high humidity and heat mixed in with the packs of lethargic mosquitoes singing their frustrated mosquitoey songs all night. We witnessed torrential rains and the subsequent floods and mudslides. When my mother worked as a social worker of sorts she experienced the poorest of the poor in the favelas of Rio. We saw people with all sorts of horrific ailments like elephantitis, leprosy, and horrible birth defects begging on the streets everywhere.

We observed death at an early age. I remember people who had been hit and killed by cars being left in the streets, covered in blood stained newspapers. I don’t remember how long they lay in the street, but as a child I can tell you it left an impression. I remember one time walking down a dirt road by my house and hearing people talking excitedly and motioning wildly with their hands. As I got closer, I could see people quickly digging out dirt by hand from what had previously been a gaping hole in the red earth.

There had been a deep cavity by the side of the dirt street which had been left open for some unknown reason. Some local children found the hole and decided to lower themselves to the bottom of the hollow to play, when the hole suddenly collapsed, burying them with heavy red earth. A growing crowd appeared and people jumped in to help with the digging. I stood for a moment hoping those kids would magically appear and then walked slowly on, moved by the knowledge that there was no 911 number or O for operator to put you in touch with police or fire services. Your fate was left to the randomness of whomever happened to be around at the time.

Tragedies like this seemed to be a daily occurrence. The pain and suffering I saw stayed with me, propelling me to work in the toughest schools where I felt I had the most to give and where the kids needed me the most.

We weren’t wealthy. In fact we lived in a tiny, noisy apartment, in a very tall building. Rio was densely populated at the time and the only way to fit everyone in was by building upward. We lived many stories up.

The electricity was shut off at certain times of the day because in 1966 Rio de Janeiro’s infrastructure couldn’t maintain consistent electricity distribution to everyone at the same time. Consequently, I was trapped more than a few times in the elevator of our highrise.

After getting stuck on my own in the darkness of the elevator at 5 and 6 years of age several times for hours at a time and having to be pulled through the trapdoor by strangers, I decided not to take those mechanical lifts anymore and made up a game. In order to save face about being too terrified to ride the elevator, I told my family I would race them to see who could get to our floor first or get down to the lobby first. I was happy to run up the many flights of stairs and it was OK with me that I never won the game. I felt I had achieved a victory, after all, by not being encased in that tomb for hours at a time. My family kindly played into my game and said encouragingly that I had gotten closer to beating them each time we raced.

Present Day

It’s so odd that after having been such active child, adolescent and young adult that today, because of my illness with ME, like many I can’t even climb one set of stairs without enduring horrible consequences to my body. I now use a mobility scooter to get around outside of the house because of the costs of that post exertional malaise (PEM) – the hallmark of this disease – exert on my body. Even though I’m still that hyper kid inside, I now use a heart monitor to help myself with pacing.

I was trapped before as a child – in those elevators in Rio de Janeiro. Now I’m trapped within my body. It’s dark and scary, having a disease that neither I nor others fully understand. Those elevators of my childhood worked until the electricity was shut down. Likewise, my body worked until my power source was damaged, but this time, my body doesn’t just shut down for a few hours each afternoon. It shuts down every day all day long.

Little did I know that those white undergarments flapping in the wind outside our car windows which resembled banners of surrender were a foreshadowing of what was to be: surrendering to a chronic illness. “ Resistance is futile,” someone once said on Star Trek and they were so right. This illness is a landslide; the caving in of a deep hole, burying you neck deep in thick, immovable earth. There is no resisting it. You must move with it as it carries you off like an avalanche, or you won’t make it.

I’ve had a hard time coordinating my will to the reality of my body’s condition. My will continually tells me I can do things that I can’t without paying a huge price. The real data of the heart monitor helps temper my naturally boisterous and hyper will which wants me to do everything right now! I pay attention to what my heart rate is and what my anaerobic threshold is and I stop well below it in order to avoid spending days, weeks, and even months in bed recovering. Even then, it still happens from time to time when reading or thinking too much, or being overstimulated by sound or light which bring on my PEM (or Post Exertional Neuro-immune Exhaustion).

It’s emotionally as well as physically painful to be confined to bed day after day, week after week, month after month, year after year and to be kept from who we truly are in our souls. In my mind’s eye, I’m still that idealistic, carefree 24 year old teacher in love with teaching and working with my students. I still yearn to do my bidding through teaching, to be setting my students free through education, to have them be all they were meant to be. All the while, I long to be set free and be who I know I was meant to be.

There is such a need for medical help for our patient population. People very debilitated by this disease often live in isolation with no help. Conditions are so poor for our fellow sick community members that patients continue to commit suicide from the isolating despair of their lives and/or the physical suffering they can no longer bear. And no one comes looking for them anymore. No one is tracking our lives or our deaths. Deaths are also resulting from cancer or heart disease or some other opportunistic infection or disease our bodies can’t fend off.

We aren’t able to just walk into a doctor’s office off the street or into an emergency room and get the help we need. Many doctors don’t know what to do with us and, sadly, some want nothing to do with us. I went through four primary physicians who were open to taking on more patients at the time who rejected me as a patient because I was very upfront about asking whether they would work with a patient who has ME. I didn’t expend energy going into their offices. I simply talked to their assistants, informed them I had ME and they all called back to say that it wasn’t a good fit or that it wouldn’t work out. The fifth physician, much to my surprise, welcomed me with open arms. It’s sad that I or anyone in our patient community should be surprised when we find a clinician who believes us or doesn’t have a misconstrued view of what this disease is. He’s not knowledgeable about the disease, but at least he listens to me and believes me.

We don’t have any FDA approved medications or treatments. We don’t have official biomarkers. We have things the specialists look for like natural killer cell function, viral titers and the VO2 max test which shows how efficiently (or inefficiently) our oxygen is being used within our cells. A very low percentage of medical students ever hear about ME.

When I go to the E.R. for help, most times I don’t say I have ME unless I feel they are willing to truly listen to me. Mainly, I reveal only portions of my diagnosis: Common Variable Immune Deficiency, Orthostatic Intolerance, and other conditions which are deemed legitimate by the medical community.

There is a stigma attached to this disease. We’ve been ignored for many years by the federal government and medical community because they have felt that what we are experiencing is a psychological disease. Most of the research on ME has been done by individual non-profit entities, but that is very slowly starting to change. Our advocates keep slogging through, trying to make people listen to us to in order to acquire federal research monies which are commensurate with our disease burden. It’s hard to garner the attention in order to be seen and heard, though many people have tried for years.

I don’t live in a third world country anymore, yet often with this disease it feels like I do. Sometimes it feels like I’m an unwanted illegal alien in my own country without the ability to access the resources I need to survive. I expected much, much more of my country of origin. ME must be admitted to the big leagues and become a household name as readily recognizable as cancer, MS, HIV, or lupus.

I also feel grateful and count my lucky stars every day that after 26 years of having this disease, I somehow gained access to see one of a handful of true specialists in ME that reside in this country. Dr. Daniel Peterson of Incline Village, Nevada, has provided treatments and answers for the last six years that I never had before. I have learned so much and feel so secure in his extremely talented hands. I have ascertained that I have Common Variable Immune Deficiency which means my immune system is impaired and is susceptible to infections, and that my body doesn’t produce enough antibodies to fight off infection. I have become acquainted with the names of the many viruses that haunt my body.

I now understand, after 32 years of having this disease, how to pace as best as I am able while wrestling with my wily will. I have become knowledgeable about what my anaerobic threshold is. I have grasped what NK cells are and know what level mine are at after each lab test I complete. I have become knowledgeable about my brain inflammation and what causes it. I have become aware of numerous medications that are beneficial and the kinds of anesthesia for dentistry and surgery to avoid. There are so many other things I have been taught, and it is critical information that all patients should be privy to. I have met some of the kindest, most talented, and empathetic people I have ever met before. I love our patient community!

I understand the pain and suffering caused by living with a chronic illness and the loss of so many distinct parts of our lives: the loss of our lives as we once knew them, the loss of our identity and our productivity through work, the loss of our finances and financial security, the loss of our friendships, our spouses, and our connections to our communities and loved ones, and the loss of activities like reading, dancing, travelling, and going out to dinner. Many of us have suffered the loss of credibility and standing in our own communities because of stigmas attached to this disease. So many patients suffer these astounding losses quietly and in isolation. We must look to HIV and other diseases which were once marginalized, but have now found acceptance and resources for our inspiration. We must examine their blueprint for success so we, too, can shed our erroneous stigmas and gain the assistance we so desperately need.

Though I am no longer able to work and this disease has brought about many losses which are hard to bear, my world has expanded by virtue of being able to access a center of true medical excellence. The infusion room where I receive treatments has afforded me the possibility of getting to know wonderful patients and fabulous nurses who have become dear friends. Though I may not be able to travel yet, my world is expanding as well through the virtual friendships I have made through the chatrooms for ME. Having the opportunity to be treated by a doctor who is world renowned means getting answers to aspects of this crazy disease I never had before.

Reading the latest information online about the most up-to-date research helps encourage my hope that one day we will have an answer for everyone. The gift that I have received from this awful disease is that I am peeling back the layers of the onion that is my life. I am discovering who I am at my core. I am discovering that though I’m no longer able to work and produce in regular ways, I am valuable just by virtue of existing. I’m learning who the real people are in my life; the ones who, like my husband, show up consistently no matter what.

Many ME patients handle their losses in different ways. I am learning how to take lemons and make lemonade as best I can. The hardest time for me was not becoming sick, but letting go of what was and accepting what is for the time being. Everyone manages the illness differently and there is no one right way of doing so. My way of making it through the twists and turns of coping with this very difficult disease has been to find a loving, healing, and accepting church community through the Episcopal Church. They have supported me by sending someone out to visit me at home once a week. They have also supported me by becoming more aware of disability and “ableism.” It’s a beautiful thing to be greeted by love and understanding when you haven’t been. The sheer notion of acceptance takes my breath away. I want it to be like this everywhere for everyone. I don’t want anyone marginalized for any reason.

I understand that this may not be the road for many of you to travel. I feel everyone must find what works best for them. I can only share my experiences of hope and strength through what has worked for me. I discovered St. Perpetua through some reading I was doing and felt an instant connection with her world experiences, even though she lived 1,815 years ago.

I hold St. Perpetua as a symbol to aspire to because her credo was to not let suffering be a stumbling block, and I was suffering mightily at the time I discovered her. This illness felt like a suffocating noose around my neck. It’s easy to slip into a very low mood when focusing exclusively on all the things that are not going right and the hardships of living that our disease provides day-to-day.

I resolved, like St. Perpetua, not to allow my illness to be a stumbling block in my life and take all my joy away. I am fortunate to have a mobility scooter and a lift on the back of my car which affords me some independence away from home. I continue to seek out more information about this disease. I have found through a recent tilt table test that orthostatic intolerance is much more of an issue than I had previously thought. Compression pantyhose and medication designed to pump up my blood volume have enabled me to have more precious time out in the world.

I continually work on acceptance of my limitations and working within the confines of this disease. The more I resist and try to control the outcome, the more I stumble and the worse I feel both physically and emotionally. I’ve learned to ride the avalanche. That doesn’t mean that I won’t ever give up trying new things, learning, and attempting to regain some abilities. I won’t give up striving to help my fellow patients by trying to spread awareness, however and whenever I am able. I’ve learned a huge lesson, though it was a very difficult one. Simply put, my needs must come first always. That’s a tough one when we are taught to put those around us first. It’s about self-preservation and survival.

I have a very practical prayer out of the Book of Common Prayer from the Episcopal Church which helps ground me. I read it every morning whether I can get out of bed or not.

This is another day, O Lord. I know not what it will bring forth, but make me ready, Lord,

for whatever it may be. If I am to stand up, help me to stand bravely. If I am to sit still

help me to sit quietly. If I am to lie low, help me to do it patiently. And if I am to do nothing,

let me do it gallantly. Make these words more than words….

I do take these words and make them more than words found in an old prayer. I work on making them my daily reality and my mantra. You don’t have to believe in God to believe in the power and fortitude you possess within and that you are worthy and valuable and good just because you exist. I imagine these words on white banners displayed for the world to see, much like my mother did when we were little kids with all those wet undergarments that needed drying.

Unlike those flapping light-colored unmentionables of my youth, I want the world to see our disease and all of us, not as symbols of surrender, but as we are: as brave warriors living with a debilitating disease and proclaiming our worth, our hope, our solidarity with one another and ultimately our victory over this humbling disease.

How Do You Cope? Health Rising’s ME/CFS/FM Coping Stories

If you’ve found a way to cope with your illness that you think might help others please tell us your story.

Health Rising’s Quickie Summer Donation Drive is On!

Health Rising’s Quickie Summer Donation Drive is On!

thank you for posting!!!

Thank you for reading!

Thank you Terry Gilmete for sharing. In many ways your story is like mine, overseas to a third world country at kindergarten, M.E. at the age of 24, child of the world. It’s been 33 years for me. I was blessed to improve but still always a daily struggle. Brain inflammation, wish I could pick your brain about that. I wonder what treatments or druga you’re referring to.

Hi, Bethany,

Our stories sound eerily similar! We are third culture kids!

Which countries did you live in? I’m so glad you’ve had improvement though the daily struggles are there. I have been blessed with being able to access to anti-virals (oral form of Valtrex and IV infusion of Cidofovir, commonly known as Vistide,and Ampligen (not available at this time) which I accessed through a clinical trial with Dr. Peterson. I have had ups and downs with this disease like many though the last 10 years have been the most difficult.

Thank you for sharing your story.

Every morning I will read the prayer you quote, I think it will help.

That’s a great idea Diane

Hi, Diane,

Thank you very much for taking the time and energy to read it. I’m glad you liked the prayer! I have found it has helped me greatly!

I plan to copy your prayer. I have been ill for 37 years. My husband left after a year, because he was being told I ‘wanted to be sick.’

During a time a few weeks ago, I was undergoing tests for eye surgery. A nurse rested a friendly hand on my shoulder, because I was beginning to show exhaustion from all the testing. I gently squirmed my shoulder from under her hand. She took offense. I explained “I don’t mean to give offense. But nobody touches me except people with sharp pointed objects. I have to remain without touch, even though I want it, because if I did let someone get too close, I would shatter.” For me, not being touched by someone I love is the hardest part. I was a happy, joyous, funny, giving person. I was also a happily libidinous wife. Missing that kind of intimacy is worse than pain, worse than short term memory loss, just worst. It took almost 6 years before I was taken seriously. Even then, by only a few special doctors who did know and believe me. I was also an aerospace worker — a technical illustrator, graphic artist, other allied skills. Even after I became ill, I kept struggling to work. I didn’t leave my aerospace job until I left it, for the SEVENTH time, by ambulance. I was lucky they sold me Long Term Disability. But even that vanished after I turned 65.

I have all the same symptoms, plus a few more. When I get up and the room spins, I sometimes end up in an awkward pose, waiting until I am steady. Then I award myself points, as if in gymnastics. “Yay, it’s a 6.0!” Occasionally, friends laugh with me, not at me. Eventually, both of my adult children came down with it. At least, I was able to help them get their disability. Both of them had previously served in a branch of our military, so at least, they get their medications free (if they can slog through all the red tape)

I can only walk 50 feet, or five minutes, whichever comes soonest. Yet, I cannot qualify for a scooter. Law says you have to need it to get around inside your home. I live in a very small home. I can and do drive, and Live in a rural area. It’s 81 miles to the nearest Walmart, where I can use the scooter. But I have to rest up for days after driving that round trip. I unload the cold/frozen stuff first. The rest can just sit there until I feel better. Sometimes, I put away stuff one or two cans at a time. To do housework, I wait until the commercials. When they are over, I sit back again. It keeps me from overdoing.

Currently, I sleep in a recliner. I cannot sleep in a regular bed, and cannot afford a hospital bed. I need to be cradled like an egg to sleep at all. I take certain medications in order to sleep at all.

For now, I have adequate pain relief, and if my frazzled memory is working at the time, I try to stick to a routine that works for me. I live in a town with an 84-degree ‘swimmin’ hole, and once an active SCUBA diver, I can still swim, without hurting myself the way most exercises do.

I am encouraged that we have these forums, and thank You for your poignant letter. I truly can identify with what you endure. But we all experience it in our own way.

Hi, Nikoli,

I’m so sorry your husband left a year ago. It’s horrible to have this disease and to be blamed for it as well. ME ruins lives, but the stigma of having it robs people, too. I love your sense of humor (awarding yourself gymnastics points as though you were at a meet) about the very sad and difficult things you live through. How sad your children developed this disease (but I hear it so many times), but am happy for the fact you have been able to guide them through the disability process. What a blessing! And I’m happy you are figuring out a routine to clean around the house and to swim a bit without overdoing it. That’s a 10 in my book!! Thank you for sharing your story and commenting on mine!! I wish you well!!

Nikoli,

I understand completely about your husband leaving, the pain of not being touched, the loss of intimacy was unbearable for many many years. I was the same wife as you described. Happy, loving, funny, kind and my only sin was fibromyalgia. The big difference is my husband didn’t leave! He had been on SSDI four years prior to when I had to stop working. His was a mental disability which he did nothing about other than self medicate with alcohol. So even though he is here physically he’s been gone for 10+ years. I was so scared of not being able to support myself, having to leave my home plus FMS was debilitating for many years and I had hope. He filed for divorce in April claiming he could never quit drinking living in our house. He equates his alcoholism as the same as my FMS. I’m no longer afraid, have continued to make progress with FMS, realized he was more detrimental to my health & know I’ll survive.

Thank you, beautifully written. I will be writing that prayer in my ‘hope’ notebook.

Hello, Eimear,

Thank you for taking the time to read my story and sharing that the prayer has brought you hope! All my best to you!

Thank you Terry for sharing your journey. Your heart. Your hopes and dreams. You, dear one, are a light that has brightened my darker days many times.

Hi, Nita

You are so very kind to say so! Sending hugs and love your way!Thank you for taking the energy to read my story…I know it took much effort and many spoons to do so!!

Beautifully written! Exactly what I needed to read today. I have been suffering imensly. The prayer really resonated with me. Thank you for sharing this.

Hi, Larissa,

I’m sorry you’ve been suffering so very much, but am glad the prayer resonated with you. My best to you!

Thank you Terry! It was so thoughtful of you to take the time and energy to respond to each person! I wish you all the best!

Beautiful and inspiring. Thanks so much!

Thank you for your generous comments, John!

I want to thank you for sharing your story too. I also have copied your prayer. I hope it will give me the grace and peace to accept this illness but, at the same time, never give up hope.

Hi, Donna,

Thank you for taking your time and energy to read this story. I hope the prayer instills hope and peace for you. Surrender? Never!!

Kudos, my good friend!

Thank you, Marilyn!!

Thank you for sharing your story with us!

I copied your prayer also!

Hi, JL,

You are so very welcome! Thank you for taking your precious energy to read it!

Thank you for sharing your story, Terry. A truly uplifting read. I have been affected by ME for much of my 69 years, I realise looking back, but it has been a gradual process of many ups and downs. I have now recovered from several years’ in relapse to do a bit of volunteer work, but my life is a constant battle with my desire to “do” and my body’s need to “not do”. Thank you again, Terry.

Hi, Chris,

I’m sorry you’ve been affected for so long, but am glad you can do a little volunteering! The push-pull of the wills and needs is a tough one! My best to you!

32 years.

Terry got sick at the same time I started arguing in earnest with Drs. Cheney-Peterson for neglecting to take interest in the first clue in the 1985 Lake Tahoe Mystery illness.

They do interesting work, but I still think it was the most epic fail in medical history that they refused then, and still refuse now.

I realize this only makes people MORE angry and determined to never look into the actual evidence that started this syndrome…. but there’s not much I can do about that.

Their anger works to their own detriment.

Erik, fyi Dr. Peterson does do blood and also urine mold/mycotoxin testing.

“I realize this only makes people MORE angry and determined to never look into the actual evidence that started this syndrome…. but there’s not much I can do about that.”

LOL! Sad, but so true!

Hi, Erik,

Thank you for expressing your experience. It doesn’t sound like there’s much you can do. I appreciate you taking the time and energy to read my story.

I too will copy the prayer. The mornings are always the hardest time of day for me. It’s beautiful as are you. Thank you for sharing your story.

Hi, Anna,

Mornings are hard for me, too! You are so very kind to expend the energy reading through and to leave such a sweet and thoughtful comment!

Bless you, Terry for sharing your poignant story. Beautifully written. You are a bright light in the darkness of my life with ME.

Hello, Jan,

You truly are so very kind to say all of this!!

XXOO

Thanks for sharing your story. However, I live far away from Dr. Peterson or any other ME specialist. Could you share what anesthesias to avoid? What medications help? What to do about brain inflammation (other than following an anti-inflammatory diet)? Those of us in rural areas of fly-over states are truly lost souls.

Good question s Mary

Hi, Mary Strand,

It is truly awful that people who live in areas such as yourself have no access to ME clinicians. The truth of the matter is that even those of us who live closer to an ME specialist still may not get in due to a whole host of factors including cost, the sheer number of patients who need help, and the ability to make it to the office due to the severity of the illness. There are many ideas being kicked around, but I think telemedicine would greatly help. I have heard that several of the ME specialists do Skype or phone calls. There is so much that needs to happen to help our community access the medical care needed!

As far as anesthesia, there was an article in ProHealth that talks about these needs specifically. You can find it online under ProHealth, anesthesia, and Myalgic Encephalomyelitis.

I can’t recommend any medications specifically because I don’t know what you are dealing with, but I think following the lastest research and going into chatrooms specifically for ME has been very helpful to hear patient experiences about alternative and western approaches to treatment has been helpful to me.

Thank you for taking the time to read my story.

As a follow several decades long sufferer, I feel for the writer and can see she has a great soul. However (to HealthRising) many fellow ME/CFS sufferers sadly can’t read such long detailed write ups.

I had to put my phone’s ‘Speak Selection’ on it read the text for me.

After the entire read (to the detriment of my brain) I only managed to gain that the writer is a lovely person who has previously travelled far. That there’s certain anesthetics we should avoid (but what ones?)

That the health system is still unwilling to validate our suffering, (we all experienced that).

And a prayer of acceptance that we aren’t in much control but to accept the suffering. I actually really like the prayer even though I’m agnostic (I too copied it)

Anyway in future can we who struggle reading or taking in information please have a summarised version of these lengthy blogs?

Thank you

Roy,

I know the story was a long read for a patient population with neurological issues. Thank you for expending the energy but I am sorry at the cost to you. Great idea about summarizing the lengthy blogs like mine as an alternative. I’m glad you found the prayer helpful though agnostic. I commented about the anesthetic portion earlier under someone else’s comments, but you can find an article online under ProHealth (anesthetics and Myalgic Encephalomyelitis) which I’ve found to be helpful as well.

Obrigada Terry pela sua historia, muito linda!!!!! Eu sou de Argentina e moro no Brasil perto de Sao Paulo

Forte abraço!!

Raquel

Eu estou com Fibromialgia que é parecido a ME porem bem mais leve!!!

Hola Raquel!

Ya no hablo Portuguese pero lo puedo entender. Muchisimas gracias por su comentario acerca mi historia!! Me fasino Argentina cuando visitamos. Que pais tan bella! Mi papa tuvo una entrevista en Buenos Aires en el Colegio Americano pero no le dieron el trabajo. Me hubiera gustado vivier alli tambien! Algun dia cuando yo tenga mas fuerzas me encantaria ir a Argentina con mi marido. Que lindo vivir en Sao Paulo. Me acuerdo de haber ido a visitar Sao Paulo de nina. Te mando abrazos y lo mejor con su Fibromialgia! Mucho gusto en conocerle, Raquel!!

Terry, thank you for sharing! What an adventurous, interesting, and learning experience it was growing up abroad! I knew you know some Spanish, but I figured it was maybe from your schooling. I, too, was a very active and adventurous kid. My dad once caught me climbing over the 6 ft fence to our neighbor friends at 2 or 3 y.o. Ha! It scared him so bad that I promised I wouldn’t do that again. They had a pool. I could swim by 3, but not safe. I wanted to see my neighbor friend. What a tremendous challenge it is to be afflicted by ME & POTS etc…it challenges the body, mind, and human spirit. But, I empathize and understand others suffering so much more. I too am baffled that our U.S.A. hasn’t given much of a care. It’s a very odd experience to at times be more ill and weak than people in the hospital, yet there’s little to nothing medically they can or know how to do for us. I have hope…so much interesting research and findings (lately vs in last 20-30 yrs)! And I have faith. My faith in God also upholds me. I really appreciate the prayer. Thanks again for sharing part of your story! Hugs. *P.S. on MEAction today or yesterday they announced that a big health survey in the U.S. added 2 ME-related questions to help track this disease some! They are optional questions, but just getting that required 70% approval. States that add the questions will get a small amount of CDC finding to implement them into the survey.

Hi, Jane T!

I find that faith helps me as well, but as I said everyone has to find the way that works best for them! Thank you for the info about the survey questions being passed for the public health departments. I missed that! I will have to look that up. Thank you for alerting me to this development!! Thanks for reading and commenting!!

Thanks Terry for your amazing exposition… I too have copied the prayer…. My condition ( after 30+ years) has now been put down to Lyme Diease…

Keep writing.. you have a talent!! X

Daphne Fraser, I hope the prayer is of help and thank you for your kind thoughts!

My dear friend, you truly are an inspiration to us all. Your random notes of encouragement and love shine with the joy and love of our Lord. Thank you for writing this beautiful passage and being such a remarkable friend. I love ya.

My dear Donna,

Thank you for your constant encouragement and friendship! You are a blessing to many (including me)!!

Thank you for sharing Terry! That must have taken a while to write.

Hi, Lane!

Thank you! It took a moment or two…lol!

Terry!!!! Well written! So great to get to know you better. Though you deal with illness you are a lovely beautiful person and it shines through in your writing! It is a privilege to motor scooter through life together. Thank you for sharing the awfulness of illness but not turning it into a woe is me moment. That takes grace and strength. Thank you for writing for all of us.

Thank you, Julie!! You are so very kind to say!!

Thank you, dear friend! I know that must have taken a long time to write and it is beautifully full of information woven together to give the fullest information for others to read. I miss my life, and sometimes feel that there is a big black magic marker line drawn through my days, separating the me I am now, from the me I was. Privileged to be your friend, and blessed that we support one another!

Thank you, Rebecca! You present such a visual when you said, “big black magic marker line drawn through my days.” Sending much love your way!

Terry,

What a Blessing to have had all those adventures in your early years. Appreciate you sharing your ME story, my new friend.

If you’re up to it can you share how long it took to get diagnosed, did you have some viruses and low natural killer cells and OI? Also what anesthesia should a PWME not use?

Take care Terry. I know you’re most likely resting after the event in Sacramento.

Hi, Kathryn,

Thank you!It was such a blessing to have the opportunity to travel and live in other countries as a child. I feel like I crammed a lifetime into those young years. I’m glad I had them to reflect on when life detoured with ME.

It took me a few years to get diagnosed. I was living in Santa Cruz at the time and had an incredible chiropractor who went to the ends of the earth to help me get a diagnosis after I went through many different doctors. I finally was diagnosed by Dr. Neil Singer in San Francisco after several years which was pretty good back in those days. My chiropractor in Santa Cruz is still practicing today, though I haven’t seen her in years. I owe a whole lot to her for trying so hard. She knew how sick I was and wouldn’t stop until she found someone who could help diagnose me and give me some treatment (vitamin B-12 shots).

I really didn’t get any viruses diagnosed until I started seeing Dr. Peterson 6 years ago though I had had Kaiser for 19 years after leaving the Santa Cruz area and moved to Sacramento.

My main virus that I have had a heck of a time dealing with is Epstein Barr though I have HHV-6, and at times reactivated CMV and others I’m having trouble recalling. I have been through IV infusions with very strong anti-viral called Cidofovir (Vistide) sometimes in combination with Ampligen and sometimes alone. Ampligen always has been able to bring my Natural Killer Cell function back up, but it is not available and hasn’t been for about a year. Even if it were, it’s much too costly at $200 a bottle which you must have twice a week. I have seen it do wonders for certain patients and it truly has been a wonder drug for them. It needs to be approved by the FDA so others have an opportunity to see if it helps them.

I am also dealing with orthostatic intolerance which is why I use a mobility scooter presently. I also use compression hose to keep my blood from pooling. I use oral rehydration salts to help keep my blood volume pumped up. It has helped me make some gains in getting out in the world in more of a steady fashion. I have found the OI very insidious and about 8 or 9 years ago I just kept dropping down in my ability to function. I had to finally get a mobility scooter and lift 3 years ago in order to be able to gain some mobility out in the world again. I had a tilt test last September and I am working with a cardiologist with different medications, the compression panty hose and the oral rehydration salts. So far, the medications have not helped me. We are continuing to try.

Kathryn, as far as anesthetics, look under ProHealth online. They have a great article outlining what anesthetics to avoid and why.

Beautifully written and articulated everything I experience and feel. I pray we are on the edge of answers from the OMF and we will all be vindicated after the years of stigma. It cannot come soon enough. I have had the illness 30 years exactly but at the menopause it progressed to a new level. Love to all my fellow sufferers. It is the ignorance and blindness of many of the the medical community (and its impact on lack of funding and researchers) that has prolonged our suffering. Chris

Chris, I agree with you. I reached a new low when menopause hit!! I pray we are on the edge of answers and that vindication for the stigma we’ve had to live with comes too!Thank you for taking the time to read and comment!

Oh dear! That is not good news. I first got sick when I was 18 (and have now been sick for 24 years) but the illness has worsened as I enter peri-menopause. This seems to be a common (and possibly under investigated?) theme for many women with ME. If you have enough energy to reply can you let me know if it gets better post-menopause? Dare I even ask?? 🙂 Thank-you for your amazing story. I loved reading about your childhood. Sounds like you had a lifetime of experience in the first 25 years! All the very best with your illness journey. x

I wouldn’t be surprised. It would be good to get an ME/CFS experts take on this.

Beautiful story. I commented just yesterday on an ME site that I wanted to know what people do to cope in the really hard times. Very timely article for me. Thanks

Judy,

I’m so very glad this was timely for you! All my best to you! Thank you for reading and commenting!

May the efforts and action that is being taken by the ME/CFS community bring a deafening cry upon the ears of those who can bring about the change so desperately needed in the medical and political arenas.

It’s hard to believe that anyone in a position of power who read Terry’s story would be able to disregard ME/CFS afterwards.

Cort,

Thank you again for this opportunity to put my story out there. All our stories are valuable and worthy of being heard. Mine is only one story! I hope others who are able will step forward and do the same. Thank you all for the warmth, affection, and encouragment you have so generously given! I do believe I have gained so much more than I have given! Love you all!!

Thank you, Michael! You have contributed in a huge way of helping our voices to be heard by dedicating half the proceeds to your beautiful jazz instrumental Beachwalk to Simmaron Research. Thank you for supporting my husband and I with you and your family’s friendship and all you do for the ME patient community.

Terry!

All the beautiful, amazing things I did not know about you. Thnak you so much for all the ? you put into this beautiful essay. Hope to see you next trip!!

Hi, Cheryl,

Thank you so very much for your feedback, my friend!! I hope to see you on your next trip out to California!! XXOO

What a beautifully written piece…I feel so moved, inspired, and full of hope.

Wow. A rare piece of art mined by Twitter 🙂

Kate Currer,

How kind you are!! Thank you!!!

Thank you for sharing your story. So many of us can relate to your excitement and joys in life prior to this illness. My son became ill at age 5 – 1986 after a distinct, neurological illness following Epstein Barr infection. What happened in the 1980s?

Hi, Merida,

Thank you for your thoughts! A lot of us got sick in the 80’s!! There was an extensive timeline of the cluster outbreaks for ME and I saw it in either Health Rising or on Pro Health. Maybe Cort Johnson can help us find that timeline!! It would be interesting to see how many cluster outbreaks there were in the 80’s!

Terry,

I love your story! It’s inspirational to read about how others cope. I don’t have ME I have FMS & I’ve made what I consider major progress over the last several years. Even while dealing with an alcoholic husband & the end of my 30 years of marriage. I am a spiritual person, I believe in my faith of Jesus but don’t attend any church. I am very compassionate about the suffering of so many people all over the world & my hope is to start volunteering on a regular basis for one of the many organizations in my area. It took me way to long to accept that my alcholic husband was beyond my control plus was unhealthy for me, impeding my progress with the constant turmoil, walking on egg shells, waiting for the next shoe to drop etc. I am starting a new live at the age of 63. I have to be honest that I know I’ll have pitfalls many times. So again thank you for your inspiration and will also copy the prayer.

Hi, Marsha,

I’m so very glad you have made progress over the last few years! I’m glad you were able to connect with it! Hope the prayer is of help.

Terry,

Your story is so beautifully written that it should be seen by a broader healthy audience to educate about ME. Have you considered submitting it to local publications?

Thank you for sharing your story.

Obie,

Thank you so very much for your encouragement to look at submitting my story to local publications in order to be seen by a broader audience! You’ve inspired me…I will look into it and see if anyone bites!!

Wow, Terry! You have written a beautiful piece that distills your whole life with heartrending clarity. The contrast between your youth with its aching promise and your life after ME is expressed as dramatically as one experiences it. I too became ill in the 80s, my ambitious, promising life amputated as people stood back in confusion, pity, and sometimes satisfaction, and I receded into the background of life. Or I was made to back off from people living worthwhile lives, working hard, not indulging themselves and making a burden of themselves. You have wisely skipped that part. Now at 63, alone for more than 20 years, impoverished, I cannot afford the possibly helpful medical treatments anymore. I threw all the money I’ve ever had on trying to turn my health around. It’s shocking and horrible how many people regard me as a monumentally irresponsible person who squandered her life and her money, and who deserves nothing better than her current life of isolation, exhaustion, and pain. Even my two sons for whom I sacrificed everything have backed off from me, unwilling to even understand the validity of my suffering. I too found a new religious community at the age of 50, the Baha’i community, and for a time they were wonderful – as long as I could act like a “normal” person. Most of the time, I’m too sick to attend events. However, my only true friends were made in that community, and I am grateful every day for them. Thank you for sharing your story and the lovely prayer. God bless you.

Hi, Lori,

Thank you for your kind thoughts. I’m glad you have friends in the community who understand and support you. It’s so very distressing to lose the understand and connections with those who are our closest allies and family members. Sending good thoughts your way!

Terry,

Thank you for your beautiful sharing. I am often staying in the Sacramento area,so I was wondering what doctors you have found in Sacramento that understand your/our condition?

I have been going to the clinic in Stanford and have been perscribed leflunomide which I am hesitant to take. I’d like another perspective.

Hi, Prashanti,

Thank you for taking the time to read my story and to take time to comment! I appreciate your feedback. Unfortunately, I don’t know anything about leflunomide. It’s hard when we are presented a treatment option and we aren’t able to go to another doctor for a second opinion. I hope you are able to find the feedback and input about the treatment you are looking for! Take care!!

I have lost so much to ME. I am alone most of the time. Have no doctor that gets will listen. He is clueless. I told him I was mostly bedridden, he asked why. I have no car. Just getting food is a chore. I am so tired.

.

Thank you so much for sharing your story, Terry.

I love the prayer that you use!

I found an interesting book that spoke to me when I was going through a very rough time. It is called “Defy Gravity” by Caroline Myss. It has some good prayers in it.