Dr. Klimas spoke on the IOM report on ME/CFS at the recent federal advisory panel for chronic fatigue syndrome (CFSAC) meeting. She explained how the report was done and addressed some rather hot controversies that have sprung up since its publication. This was the first time an IOM report panel has publicly done so.

Panel Composition

The panel members included Margarita Alegria, Lucinda Bateman, Lily Chu, Charles Cleeland, Ronald Davis, Betty Diamond, M.D. Theodore Ganiats, Betsy Keller, Nancy Klimas, A. Martin Lerner, Cynthia Mulrow, Benjamin Natelson, Peter Rowe, Michael Shelanski. The report was also reviewed by a long list of ME/CFS experts.

Dr. Klimas said the report was an enormous amount of work. In between four long meetings the panel members assessed thousands of articles. The public workshops also greatly influenced the panel’s report, with the committee being greatly touched by the patient stories.

The press, of course, was very favorable (and continues to be favorable. Two more articles in the last week focused on the IOM report.) The JAMA article was downloaded 43,000 times by non-subscribers. Six months later the IOM report for ME/CFS is still one of the top ten downloads on the IOM website – something the Institute of Medicine was very pleased to see. (Since the ME/CFS report was released in February the IOM has produced over 60 reports on issues ranging from cancer to obesity to emerging viral diseases.) That high interest could be good news for the next report Dr. Klimas believes should be produced – on therapeutics.

All that attention suggests, of course, that for all the inattention given to ME/CFS by the NIH and CDC, the medical community is actually quite interested in this disease.

The Almost Biomarker

The panel agreed that reduced NK dysfunction (reduced cytotoxicity) discriminates ME/CFS from healthy controls, but NK cell dysfunction did not make the diagnostic criteria. The reason for this was that outside of specialized labs – which most doctors don’t have access to – the quality of NK cell cytotoxicity tests is poor. (This is because most labs take 48 hours to process the test but the test is only good for 8 hours.)

Dr. Klimas noted that the CDC is doing work on NK cell testing now. She hoped that a widely available, high quality NK cell test will be on the market by the time the diagnostic criteria are revised. (A biomarker indicating that part of the immune system is whacked in ME/CFS, would, of course, be a very big deal in helping to change the conversation around this disease.)

Dr Klimas noted the IOM panel was prevented from delivering more positive findings because of a lack of follow up for many research studies.

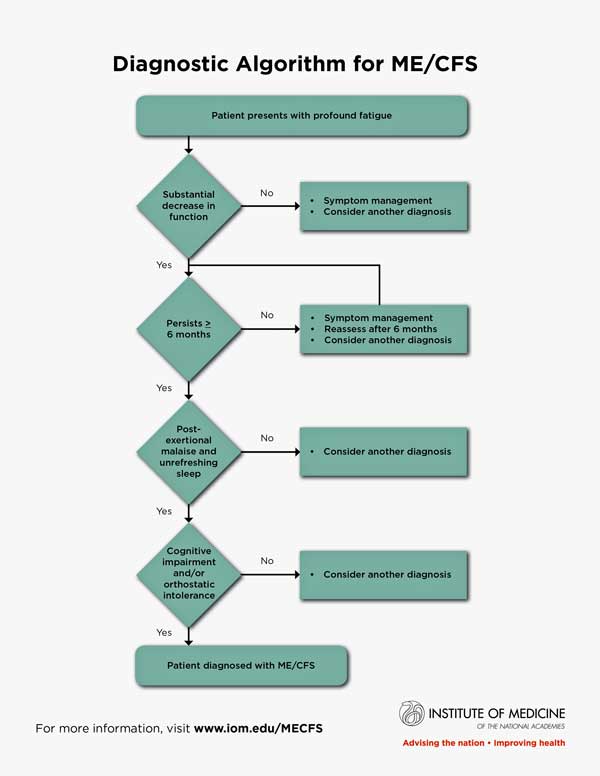

Diagnostic Algorithm

Getting doctors who knew nothing about the disease up to snuff on it was the prime focus of the report

Dr. Klimas said that the primary factor driving the committee’s report was the 85% of chronic fatigue syndrome patients who have not been diagnosed. Getting that number up played a role in every decision the panel made. Doctors who know little or nothing about the disease were the focus of the criteria.

Their primary goals were

- to have doctors understand that ME/CFS is a serious disease they should be on the lookout for

- to have doctors be able to easily recognize and diagnose it

- to have doctors treat the symptoms present in it and

- to avoid misdiagnoses and harmful therapies.

To that end the IOM panel produced a simple diagnostic algorithm doctors could easily memorize. Even though Dr. Klimas helped to develop the ICC and CCC definitions she said she still needed a cheat sheet to remember them and the Fukuda definition.)

The panel strove to incorporate symptoms that were common and which discriminated ME/CFS from other illnesses. They agreed that post exertional relapse is the key discriminatory symptom in ME/CFS. It’s rarely, if ever, found with the severity that occurs in ME/CFS.

The cognitive impairment and dysautonomia (orthostatic intolerance) symptoms help differentiate the illness from other illnesses, plus unrefreshing sleep is very common. (Questions have been raised regarding orthostatic intolerance because it’s not as common as the other symptoms. It appears to have been included because it’s a standout symptom that alerts doctors to the possibility that ME/CFS is present.)

Symptoms such as pain, infectious triggers, gut and urinary problems, sore throat, painful lymph nodes, sensitivity to stimuli that are important were not discriminating enough, not common enough or there wasn’t enough data on them to include them in the definition.

The report also offered a list of signs and questions doctors can ask to get clearer on the symptoms present in ME/CFS. For instance, with regard to post-exertional malaise, it suggests doctors be on the lookout for patient that talk of “crashing or relapsing”. They recommended doctors ask questions such as:

- What happens to you as you engage in normal physical or mental exertion? Or after?

- How much activity does it take you to feel ill?

- What symptoms develop from standing or exertion?

- How long does it take to recover from physical or mental effort?

- If you go beyond your limits, what are the later consequences?

- What types of activities do you avoid because of what will happen if you do them?

Biology

The report also states that the immune dysfunction found is severe enough that doctors should be concerned about viruses reactivating. With regards to the HPA axis the adrenals are OK but there is evidence of HPA dysfunction and serotonergic signaling problems.

The report concluded EBV can clearly trigger ME/CFS but there’s insufficient evidence to conclude that all ME/CFS is caused by it or that it is sustained by an ongoing EBV infection. (Dr. Lerner surely fought hard for a more definitive statement :)) With regard to bacterial or other infections they concluded they may be present and may reflect an immune dysfunction. More research is needed in all these areas.

The Controversy

Then Dr. Klimas cleared up an important misconception about the report and she addressed some of Lenny Jason’s concerns. First some background (from me – not Dr. Klimas)

Lenny Jason’s critiques have undoubtedly lead many in the ME/’CFS community to take a jaundiced view of the report. A recent Facebook comment saying something to the effect that “if only the IOM panel had had Lenny Jason they wouldn’t have made so many mistakes” probably summed up the view of many.

In a recent blog Jason portrayed the report as a kind of epic failure and wondered if anything can be salvaged from it.

Jason has pointed out in a string of papers and blogs, major mistakes he believes the panel made. In a recent blog titled the “Battle for Justice” he, if anything, sharpened his criticism of the report. He portrayed the report as such a set-back that he wondered if there was “any way to salvage the damage inflicted on the larger patient community by well-intentioned scientists from the IOM?”

That this panel – packed with the experience and brain-power it had – would have made so many major mistakes has always been bewildering to me.

Dr. Klimas’ testimony was the first time an IOM panel member has chosen to respond to Jason’s critiques.

Clinical Definition – Not Research Definition

Dr. Klimas reiterated (perhaps for the fifth time in her presentation) that the IOM definition was a clinical definition – not a research definition. (To my regret I had missed this distinction entirely.)

Klimas asserted that the critiques of the definition mistook it for something it was not – a research definition

It’s an important one. Clinical definitions are by their nature inclusive; they’re drawn up so that no one with a disease is missed. Research definitions, on the other hand, are exclusive – they’re drawn up to ensure that only people with a more or less pure form of a disease are included in research studies. By their nature they exclude a substantial number of people who have the disease but who also have confounding factors.

All of the complaints regarding the new definition – that it’s too broad, that it brings in too many people, that it doesn’t have exclusionary factors, that some people with depression fit it – are based on the idea that it’s a research definition.

It’s not…. The IOM report clearly states the panel was tasked with developing an

“evidence-based clinical diagnostic criteria for ME/CFS for use by clinicians” and that

“These more focused diagnostic criteria will make it easier for clinicians to recognize and accurately diagnose these patients in a timelier manner.” Plus

“the committee hopes that the diagnostic criteria set forth in this report …will promote the prompt diagnosis of patients with this complex, multisystem, and often devastating disorder; enhance public understanding; and provide a firm foundation for future improvements in diagnosis and treatment.”

Research is never mentioned. That distinction removes several issues (prevalence, exclusionary factors) that have been dogging this report.

Increased Prevalence

Jason’s analyses indicated the definition would increase prevalence rates significantly – so much so that he recently compared it to the CDC’s infamous Empirical Definition.

“Our published work now suggests that these new criteria would almost triple the prior CFS prevalence rate….This inadvertent action accomplished much of what Bill Reeves and the CDC had attempted to do a decade ago when they proposed an ill-fated expansion of the case definition.”

These are strong, provocative words. Associating the IOM diagnostic criteria with Dr. Reeves and his hated “Empirical Definition” is sure to assign it to the second circle of hell for many people with ME/CFS. Jason also indicated that the IOM criteria identifies a group comparable in size, produced by the much maligned Fukuda criteria.

In the light of the reports goal of increasing diagnostic rates, Jason’s findings can actually be viewed as an asset, not a failing. Similarly, Jason’s objection that the criteria selects patients with less impairment and fewer symptoms than a more restrictive four symptom criteria fits the IOM panel’s goal of drawing a broad net.

A clinical definition should not only define the more severely impaired. It should capture all permutations of an illness – from severe to mild – so that doctors can make a diagnosis when they see it.

Exclusionary Factors

Jason’s taking the report to task for not including exclusionary factors struck a chord with many. He stated that the “the erroneous inclusion of individuals with primary psychiatric conditions…. would have detrimental consequences for the interpretation of epidemiological, etiological, and treatment efficacy findings“.

That made sense if there were findings to be found with this group, but again, there are no findings to be found in this group of patients. The IOM’s diagnostic criteria were developed to help doctors identify and treat ME/CFS patients – not produce research findings about them or to use them in clinical trials.

Jason’s findings about depression were depressing – but only if the criteria are used for purposes they were not intended

Another stunning finding from the DePaul group indicated that 47% of people with melancholic depression meet the SEID criteria. Jason argued that the lack of exclusionary factors would hamper clinical trials:

“including individuals in treatment studies who have a primary affective disorder but were misdiagnosed with SEID will lead to difficulties in interpreting treatment effects for individuals with ME.”

Clinicians do need to weed out depressed patients from ME/CFS patients (with or without depression) in their office but that is simply part of the diagnostic protocol they should follow. Jason also argued that the report should have had a recommendation for a mental health evaluation or structured clinical interview. Given the high percentage of people with melancholic depression who meet the criteria that’s seems like a good idea.

Most of the time the misdiagnosis, though, in ME/CFS probably goes the other way; i.e. people with ME/CFS are more likely to be misdiagnosed with depression or misdiagnosed as only having depression than depressed patients are at being misdiagnosed with ME/CFS.

This is only an issue if the IOM definition is used in clinical trials which would be a misuse of the definition.

Dr. Klimas simply stated that the IOM report did not include exclusionary factors because exclusionary factors are not included in clinical definitions.

Lenny Jason – Off the Hook?

Jason has come under some criticism for not serving on the IOM panel or even as one of the expert reviewers. The fact clinical diagnostic criteria, not research criteria were being developed, brings up the question whether Jason was needed as much as was thought. The ME/CFS experts on the panel were mostly physicians – and given that they were tasked with helping other physicians identify ME/CFS – they were clearly the right people to have on the panel.

Lenny Jason On the Hook?

So what about Lenny Jason and his string of highly negative studies and sometimes rather inflammatory blogs? He’s been treating a clinical definition as if it was a research definition and hammering the heck out of it. I asked him about that. He referred to the muddled definition problems that have historically prevailed in ME/CFS; i.e. research definitions treated as clinical definitions.

“Regarding the IOM, as we know, the 1994 (Fukuda) criteria tended to be used both for research and clinical purposes, although that was not the original intention of it. So, when only one criteria is announced, there is always the danger of a similar situation occurring again.

Clearly, what is needed is both a research and clinical criteria, and had both been worked on at the same time, the confusion would be much less. We do need both, and hopefully this will need to occur in the future.

For now, the IOM has one criteria that might very well be, regrettably, used for both purposes and should that occur, the dangers I have alluded to would be evident. I have tried to suggest ways that this can be avoided in my blog.”

Unfortunately, Jason’s papers and blogs don’t make the distinction between the clinical definition the IOM definition is, and its possible misuse as a research definition. They treat the IOM’s clinical definition as if it were a research definition. That has lead to some confusion.

It’s safe to say, though, that Jason’s critiques have so exposed the problems of using the IOM’s diagnostic criteria as research criteria, that it will never be used as such :).

The Research Definition

Creating a good research definition is critical to the success of research efforts. Expect more studies on that from Lenny Jason soon.

The outstanding definition issue now is the research definition. Jason stated in an email that a good research definition “is so critical for the field”. A virtual one man band on this subject, he has been ploughing away, publishing study after study on ways to operationalize the symptoms in ME/CFS, and honing the symptom set for a research definition.

He appears to be close to producing a simple research definition that works. More data is needed, though, on how the symptoms in ME/CFS compare to those found in other diseases. Jason’s DePaul group recently released a survey intending to do just that, and Jason said several research papers will be published soon.

Then we can get into the next controversy.

Thanks Cort for clearing up the clinical vs research definition confusion.

I for one think the new clinical definition is great and can only imagine how the course of my illness might have been different if it had been available almost 20 years ago when I first got sick.

In regards to depression and other diagnoses I don’t think patients should not automatically be excluded from an ME/CFS diagnosis as long as they meet the basic criteria. One of my early symptoms was severe anxiety (probably due in part to undiagnosed orthostatic intolerance) and this caused all my symptoms to be chalked up to a mental illness when in fact I was also having severe exercise intolerance, lightheadedness with exercise and standing, unrefreshing sleep and an increase in symptoms a day or two after overdoing it. If the IOM flowchart had been available when I first got ill I could have been diagnosed and not pushed myself to keep working and exercising. I would guess post-exertional malaise (an increase in ME/CFS symptoms, not just symptoms of deconditioning) will exclude depressed people 99% of the time and when it does not those patients probably also have ME/CFS.

I read Lenny Jason’s recent blog post that you link to and I think that you should do a post on his proposal for a “tripartite classification system” that breaks patients into “ME”, “CFS (or neuroendocrine dysfunction syndrome), and just plain “Chronic Fatigue (fatigue lasting more than 6 months)”. His issue seems to not be so much with the IOM clinical definition itself rather that it is too broad for “true” ME patients whom he seems to feel are a distinct category and it all comes back to the naming issue.

The tripartite classification idea is interesting and perhaps at some point it will be induced. At this point I would be really glad if we had a good clinical definition – which we have – and a good research definition. Given how long it’s taken to develop the first and since we don’t have the second, I think the idea of three definition illness, while intriguing, is unlikely at this point.

I think Lenny is absolutely aghast at the idea of the IOM Clinical definition morphing into the research – as he should be :). I think his points are so well taken at this point that I can’t imagine that happening.

Hopefully, though, Lenny will be bring us to the point where his research definition is so bulletproof that it has to be accepted and we’ll finally have a good one.

I believe the differences in these illnesses are insignificant compared to the vast number and quality of similarities. We would be better served with increased treatment trials – expanding treatments successful in very similar illnesses like MS and making them available to CFS patients. I’m sure we would have plenty of volunteers since our current options are pretty much NIL. They need to open up treatment options not spend the next 20 years dissecting the minutiae.

Certain quite a few drugs that are used in other diseases are used in ME/CFS. Take Rituximab. Until Fluge and Mella stumbled upon it nobody had any idea it might work in ME/CFS. I’m sure others are out there – which brings to mind the Solve ME/CFS’s and Biovista’s uncovery a new drug combination their research indicated might be helpful. At some point we’re going to learn what that is…

Cort,

You beat yourself up too much over the distinction between a clinical and a research diagnosis. I am a physician, and I was unaware of any diseases having different diagnostic criteria for research and clinical purposes! As I am far from the most oblivious of my peers, I am sure I am not in the minority for having such ignorance.

I looked the concept up and came up with only two other diseases for which there are distinct criteria for research and clinical purposes: Alzheimer’s disease and Temperomandibular Joint Disease. So, I really don’t think this is a common phenomenon.

Of course there is the disastrous controversy over the CDC’s research diagnostic criteria for Lyme disease which is widely applied by clinicians and insurance companies to deny care and coverage for people with Lyme disease who do not fit the extremely stringent criteria for a diagnosis, despite the fact that the CDC itself posts a note after its listing of the “Lyme Disease Surveillance Case Definition (revised Jan 2011)” [http://wwwn.cdc.gov/nndss/conditions/lyme-disease/case-definition/2011/] that states:

“Note: Surveillance case definitions establish uniform criteria for disease reporting and should not be used as the sole criteria for establishing clinical diagnoses, determining the standard of care necessary for a particular patient, setting guidelines for quality assurance, or providing standards for reimbursement.”

So, this practice of dual criteria is a likely recipe for confusion and further suffering, I’m afraid.

Thank you for the fine reporting, as always!

Interesting. I didn’t know. That gives a good background to Lenny’s concerns as well.

Thanks

I am with Lenny on this. This clinical definition needs to be in much better shape before giving it to a standard GP and tell them to treat the symptoms.

Does anyone have faith in a regular MD with no clinical ME/CFS experience to be able to help let alone not harm us even if they get the diagnosis right? I’ve even had well meaning expert doctors treat the symptoms only to make me sicker because neither of us new how careful you have to be when giving many of us medications or even vitamins. Where is the warning about going low and slow like in in the CCC primer?

I would also like for the patients and doctors to be made aware of the specialty tests (NK ect) even if the primary doc wont order them, we deserve to be informed.

The biggest thing I see missing is a recommendation for centers of excellence where doctors can be trained in this disease especially before all our experts retire.

This is not a disease that can be treated in a 7 min office visit. Would they recommend MS patients be treated by a GP? Are we somehow less deserving of specialty care? This is such a complex disease to both diagnose and treat and I think of the last 10 doctors I went to and I would only trust one of them to even give it a shot.

They seem so worried about scaring off or confusing doctors but if they are too confused or it sounds like too much work then they are not the right doctor to be treating ME anyway.

Thank you Jamie, very well put! I have no sympathy for any doctor who finds it hard to remember ICC or CCC criteria and has to pull out a cheat sheet to make sure they get it right–so pull out the sheet already! But yeah, it might take a GP half your appointment to find the sheet and check it, so how about this: SEID criteria is used as a pre-screener by the GPs, who then REFER the patient to a specialist (like they do for far less complex diseases) and the specialist takes the extra time to pull out the sheet and make sure they’ve got it right. But that would require more specialists in this field–exactly the point you’re making.

Thanks for the interesting coverage, as ever. That distinction between clinical and research makes sense, though surely exclusionary criteria are important to make sure you have the most appropriate treatment.

However, I was hugely disappointed by Nancy Klimas’s claim that NK dysfunction would be the elusive biomarker if only a good test were available to clinicians. I’ve read the papers and seen the data within, and NK dysfunction is not good enough to be a biomarker:

1. There is substantial overlap between healthy cases and mecfs cases. That’s very bad news for a biomarker

2. More importantly, healthy controls are not the point. Doctors have no diagnostic issues distinguising between the healthy and those with mecfs. Good biomarkers need to discriminate between mecfs and other diseases that look similar, including general fatigue. Deconditioning affects many aspects of the immune system too, so at the very least highly sedentary controls are needed.

NK dysfunction is a fascinating and replicated finding for mecfs patients as a group. It’s not yet ready to be a biomarker: more work against appropriate controls is needed. hopefully that will be done.

Thanks Simon

I wonder about NK cells too. I left out the part where she said it was a good indicator of severity. Perhaps it could be part of an algorithm? These symptoms plus NK cell dysfunction suggest ME/CFS? I think there is a strong desire for a biological biomarker.

I just feel this is driven more by the need for a biomarker than the strength of the science! I think it’s more of an interesting finding that needs to be understood (esp as not unique to mecfs) than something that’s ready for the clinic, even as part of an algorithim (though ultimately it may be an algorithim with several tests is the answer). It’s perhaps the most robustly replicated abnormality, so certainly deserves more attention. Especially if it corrrelates with severity.

“She hoped that a widely available, high quality NK cell test will be on the market by the time the diagnostic criteria are revised.”

Cort a specific question, with klimas being my expert, I know that NKC Dysfunction would be only one bio-marker… but for which illness, ME or CFS? What I have heard from KLimas and Bateman is that maybe CFS is at the top of the example with many sub-classes below it, and ME being one of the more severe sub-classes. I did not hear from what was written that she thinks this would be the ONLY bio-marker as it is known that some do not have NKC dysfunction.

But if the NKC dysfunction was bad, would it be for the CFS or the ME diagnosis? I totally realize that Klimas calls it ME/CFS and Bateman before the brain study results came out used the SEID label with ME being a sub-class under that as I heard her explain that in a video clarifying her position. FYI, I am not arguing any point here on ME versus CFS or ME/CFS as the latter is what i call it. I just want to understand from a TECHNICAL POSITION as to be very accurate in what I communicate to my groups. THANKS!!!!

I don’t know..my guess is though that it would be for SEID or rather whatever the name is that matches the diagnostic criteria they created. But what about people who don’t have NKC dysfunction? A great question – Diagnostic tests don’t always apply to all people with a disease. Not everyone with Sjogren’s has high ANA titers,for instance. My guess is that it would be one possible indicator.

When they made humans – they didn’t make them simple!

The best example of a biological test that is used to help in diagnosis but has a high rate of inaccuracy is the PSA test for prostate cancer. it has a 15% false negative rate. And it has at least a 33% false positive rate (for prostate cancer). But prostate cancer is a killer. So they use the best tool they have to indicate whether a biopsy needs to be done because action can sometimes save lives.

The motivation to use an imperfect indicator is not as strong in our disease because we don’t die within five years.

The problem with low-function NK cells, beyond getting the test run right, is that other illnesses also have it. So it can’t be the only thing used in diagnosis. I would like to see a combo of symptoms (or just the activity-induced sickness symptoms) and a biological test.

I always knew the point was a clinical definition. A few years ago, when Klimas was a member of CFSAC, she said there should be two definitions: one for clinical use and one for research. She said in the beginning with AIDS, the research definition was very strict: gay men, pneumonia and the cancer (I don’t remember the exact criteria, so this list may be wrong, the point was that it was narrow). When the biomarker was found in that narrow group they knew for sure had the disease, then the biomarker replaced the criteria. Up until that time, though, clinicians, especially in areas of high occurrence, could identify the disease in someone who didn’t meet the narrow research criteria. So the doctor’s point about other diseases not having two different definitions may be because most other diseases now have a biomarker, so the biomarker defines the disease. Or the symptom is so different that there’s no question if the person has the disease, for research or clinical settings. But the fact he found two others that have two definitions shows that in some cases, it’s useful. And since we don’t have a biomarker, and the symptom severity and presentation varies in individuals, and because there is no visible sign and most of the symptoms can occur in other diseases, I think a narrow research definition would be helpful. We even now know we need to differentiate stage of disease in research looking for biomarkers.

I also think people miss that while we think of the new criteria as a tool for clinicians to go by to diagnose, I think of it as an education tool, something that will inform doctors. Just making activity-induced sickness symptoms a requirement is a huge improvement and will make them see there is a variability of function and symptoms moment to moment or day to day. Just because they look perky and well in the doctor’s office, doesn’t mean they aren’t sick, if they describe “crashes” or up a d downs. This is huge in helping doctors see the difference in this disease and depression, diabetes, etc. It’s not continuous fatigue. It’s sickness symptoms from activity. If this criteria educated clinicians on that one thing alone, I’d support it. But it does more. It also indicates that “exertion” is bad and should not be recommended.

I also appreciate Dr. Bateman said that in clinical reality, people have more than one disease all the time, maybe even melancholy depression and SEID. Clinicians consider the disease now to not be a true entity, the “wastebasket diagnosis,” because it’s what you tell a person they have when you exclude other things. But this new one uses positive distinguishable symptoms instead of every symptom possible that is also seen in other diseases and then you end up with a label that is what you have when they can’t figure out what you have. This changes it to a separate and real illness with its own different symptoms that can be distinguished from others, even if a person has other illnesses too. She said having an exclusion of other illnesses actually prevented credibility of this being a real disease. I’ve seen this in the clinician’s office. The doctors act like my saying I have CFS means nothing to them, it doesn’t mean I have a disease. It means I have fatigue where the real disease can’t be found through tests or distinguishable signs or symptoms. If dropping the exclusions gets this into real disease instead of wastebasket (I don’t know what you have so I’ll give you this made up label for your symptoms) diagnosis, then great. And from what Bateman said, as long as it is what you have when other things are excluded, then it will not be taken seriously as a separate disease that can be distinguished by its own symptoms.

And I think people forget that clinicians are much more likely to pursue other diagnoses first in the six months after the person first gets sick. Why? Because there is an effective treatment for most other illnesses: hypothyroid, diabetes, low B12, even depression. A doctor can either run a test or try out a medicine on these and find out for sure. And then they know how to fix the problem, which is what they want to do. Why would they give this SEID diagnosis if they don’t have a drug to give to fix it unless they know for sure and have explored other, more attractive, diagnoses?

Klimas also said that they considered that even now, some are refused insurance coverage for treatments in clinical settings. A narrow definition in the clinical setting may leave out the “atypical” or those in mild or early stages and prevent them from being diagnosed or properly treated. This could have real financial consequences. Klimas mentioned this when speaking to CFSAC. It would be harmful to patients. I can personally relate. If pain was made a requirement, I would not have met the criteria in the first three years. And so what would I have had? Depression they might think. Which would be a misdiagnosis and wring treatment. Early diagnosis and doctors telling patients to avoid exertion, especially in early stages, is just so important to patient quality of life and prognosis that in the clinical setting, that goal is priority 1, the way I’m thinking. No matter what criticism can be said of this criteria, if this gets more people diagnosed early and gets doctors to tell patients to avoid exertion, then it’s the biggest thing for progress for patients that can be done.

One of the commenters feel it is lacking because it did not include treatments or need for centers of excellence. That was not the scope of this study. It was not comprehensive. So leaving those things out is not a failing. As Klimas said, if more is needed, then let’s do this process with a focus on these other topics.

Thanks Tina!

I guess I must wonder if it’s such an important report to the NIH and the CDC why is it that our funding by the CDC was eliminated for this year?

The cut in the proposed CDC budget happened at the congressional aid’s level. It was included in the request from CDC.

Cort,

do you think there are favorable implications for Ampligen in this new IOM report?

Interesting article, Cort.

I have said from the start that if you look at the IOM definition purely as something to be used for clinical purposes, it arguably has some merit to it.

But I wonder what definition researchers are going to be using now. Neither Fukuda nor IOM is appropriate for research, and so far researchers (even researchers who should know better, like those out of Stanford) have seemed disinclined to use CCC or ICC.

I just don’t understand why researchers seem so unwilling to use CCC or ICC along with one of the broader definitions in their papers, so that everything is clearer.

I wonder what would have to be done to persuade researchers to do that.

Best,

Lisa Petrison

Thanks Lisa,

Dr. Klimas said she’s using CCC for her studies and some others are picking it up but most are Fukuda I think. The dig on the CCC – that it recruits more people with psychological disorders – is probably not such a problems in studies originating out of ME/CFS clinics.

The NIH is now willing to fund studies using the CCC – they used to require Fukuda – my guess, is though, that many researchers are quite conservative and they’re waiting for a consensus, validated research definition to show up. I can’t imagine, given all the work Lenny has done, that it is THAT far away – although most things seem to take longer than expected…

A layman’s question: Why should a clinical definition be less rigorous than a research one?? Isn’t it just as crucially important for a clinician to be as accurate as possible when diagnosing a patient as it is for a researcher when selecting and studying patients? I am no epistemologist specializing in the evolution of medical concepts, but this duality of clinical versus research definitions seems strange to me… – Ok if the clinical definition is a simplified, reader-friendly version of the more detailed research one, as long as both share the same fundamental elements and relate to one another, instead of being independent definitions.

Also, I don’t understand why Lenny Jason and many others insist that the IOM criteria (or even the CCC) will accidently capture psychiatric conditions. I am not talking about comorbidities, but conditions such as those 47% cases of melancholic depression MISDIAGNOSED (sic) as ME/CFS (or SEID). How can they be misdiagnosed as such if these conditions don’t have post-exertional malaise, a mandatory IOM criteria? The minute you have PEM as mandatory, psychiatry is out of business…

My aunt just died (of cancer) , and now I know that she spent the last 30 years of her life with undiagnosed, untreated ME/CFS.

I didn’t recognize it until it became severe in the last year of her life. Because lots of health conditions can cause a person to feel lousy, and my aunt wasn’t sharing all her symptoms.

During that last year of her life, her doctors at the University of Michigan Medical Center put her through all kinds of medical tests for everything under the sun. And they still couldn’t figure out what was going on with her. They knew there was something wrong in addition to her cancer. Apparently there is not one SINGLE doctor at the U of M Medical Center who knows enough about ME/CFS to diagnose it.

Just as I was about to tell my aunt what I thought she had, she figured it out herself by watching an episode of Dr. Oz on TV. The episode where he talked about SEID.

Then her cancer came back and she never got to treat her ME/CFS or find a doctor who knew anything about it.

ARGH! I wish I had known all those years that she was suffering with a mild to moderate case of ME/CFS.

Thanks for talking about Jason’s criticisms of the IOM report. I find the IOM report refreshing and hitting on the right point, to get doctors to take us seriously. Getting thrown out of an emergency room because the intern disbelieves you, the uneducated intern, is annoying, especially when the reason for being there proves to be common and not related to M.E. Having all my doctors put me at arm’s length because they do not want to be part of THAT GROUP of doctors who can make a diagnosis is astounding, but that is reality now. IOM has the power and influence to turn that social/medical snub around. Once doctors begin to make the diagnosis, they will learn what happens from their patients, and perhaps take a continuing ed class, too.

I want very much to be honest about my situation, but the specialist doctors I see for other issues like cancer screening, or everyday colds and infections, the best they can do is avoid saying anything wholly unprofessional to my face. They cannot look at me as having both M.E. and the other health issues that arise as life goes on. Now I must seek a new general physician, and I really fear having to mention my quarter-century with M.E. But I need a doctor.

I hope the IOM has full success and doctors learn how to diagnose, and begin to put their minds on how to treat what can be treated. Researchers can get along as they want; treatment and some respect are important for living with this disease.