Leonard Jason is at it again 🙂

There has been a lot of talk about how the symptoms of the PASC (Post-Acute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 Infection) patients – hereafter referred to as long-COVID patients – are similar to people with chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) but, until now, no studies that I’m aware of have compared the two.

Leonard Jason is, not surprisingly, the first to do that. Jason’s been publishing on ME/CFS for decades. His epidemiological studies, way back when, burst the bubble on the idea that ME/CFS was a rare disease mainly affecting yuppies. From pacing to disease burden, to functionality, to tracking infectious mononucleosis patients, Jason’s prodigious output has informed this field in so many ways.

Prior to Jason, for instance, the questions epidemiological studies asked about symptoms were rudimentary; i.e. if they were present or how severe they were. Jason’s DePaul Questionnaire (DSQ) – which was developed for ME/CFS – changed that for good. The DePaul Questionnaire records symptom frequency and severity and uses both scores to come up with a single (0-100) symptom score. It was only after that, that symptoms that are really bothersome in ME/CFS – those that are both frequent and severe – such as post-exertional malaise, were able to stand out.

Now Jason’s reach has extended to long COVID. His new study, “COVID-19 symptoms over time: comparing long-haulers to ME/CFS“, was recently published in “Fatigue: Biomedicine, Health and Behavior” — the Journal, it should be noted, of the International Association for Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/ Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (IACFS/ME). Jason’s certainly primed to study the long haulers. His decade-long studies of the effects of post-infectious illnesses (infectious mononucleosis) means that he’s got a leg up on other researchers. Let’s hope this is just the first of a series of insightful studies on the intersection of long COVID and ME/CFS.

The Study

Jason asked almost 300 long-COVID patients about their symptoms at two time points: one a couple of weeks after they became ill, and the other at the present time – and then compared their symptoms to those over 500 people with ME/CFS – most of whom had been ill for over two years – were experiencing. (The ME/CFS symptom data came from the Solve ME/CFS Initiative.)

The average long-COVID patient in the study had been ill for about 22 weeks or about 5 1/2 months (just shy of the 6 month duration needed to meet the criteria for ME/CFS).

Results

Demographically, the two patient sets were quite similar. As with ME/CFS, long COVID appears to mostly strike women (84% female – long COVID; 79% female – ME/CFS). Both sets of patients also tended to be middle-aged (long COVID – 45 years old; ME/CFS – 55 years old).

The symptom pattern was intriguing. At the start of their illness, long-COVID patients reported more severe symptoms than the people with ME/CFS. Over the course of 5 months or so, their symptoms tended to decline a bit. By 5 1/2 months or so, the pattern reversed itself. With the long-COVID patients feeling a bit better, they were not worse off than the really long haulers – the ME/CFS patients.

Importantly, post-exertional malaise (PEM) popped out in both diseases. PEM, it should be noted, is not a common symptom in diseases in general. It’s such an unusual symptom that it didn’t exist as a symptom to assess until chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) came on the scene.

The Post-Exertional Malaise (PEM) Crunch

While it’s possible that some degree of PEM is present in other illnesses, in no other illnesses has it played such a central role. That is, until now. PEM stood out in both the long-COVID patients and the people with ME/CFS.

Jason’s DePaul Questionnaire separates PEM into six different categories: heavy feeling, mental fatigue, minimum exercise, feeling drained, fatigue and muscle weakness, and provides an average PEM score. With the DePaul Questionnaire’s symptom score of 0-100, compare the average PEM score to those the other main symptom categories.

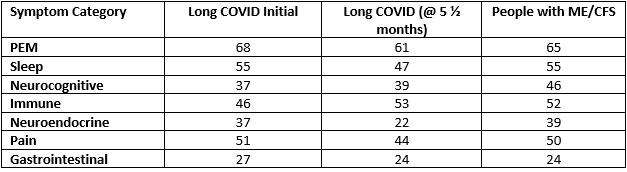

Major symptom categories*

*There’s also the orthostatic symptom category which went from 46-34-29./ I accidentally transposed the numbers for column above the immune category into the immune category. The correct immune numbers are 44, 20 and 28.

The PEM score is about 20% above other scores in both conditions. Jason’s breakdown of the PEM scores reveals that both diseases were particularly distinguished by high levels of fatigue, problems with minimum exercise and feeling drained (all in the 70s).

Trouble paying attention, unrefreshing sleep, needing to nap, soreness and muscle pain stood out as particularly troublesome symptoms in both patient groups.

Shortness of breath (62) and difficulty breathing (56), on the other hand, stood out in the long-COVID group (62). (Difficulty breathing was not measured in ME/CFS).

Early Long-COVID Symptoms Suggest Ongoing Immune Response Present

Immune symptoms seemed to characterize the early response. Later in the disease, they diminished.

The early symptoms of the long-COVID patients suggested their bodies were wrapped up in an ongoing immune response. These symptoms tended to drop dramatically (flu (59-21), sore throats (43-26) lymph nodes (31-19), fever (38-11) high temperature (48-22) over time. So did many of the formerly prominent neuroendocrine symptoms: chills (47-20), night sweats (43-24), hot/cold feelings (50-34).

Other symptom categories dropped but were more distinguished by their consistency over time. Five months or so later, pain had dropped by an average of 5 points or so and was still high (average 44). Similarly, PEM (68-61), sleep (55-48), and gastrointestinal symptoms (27-24) remained mostly steady. Neurocognitive symptoms (difficulty remembering, understanding, talking, etc.) was the only category to worsen (38-39) but only slightly.

Five months later, the core symptoms of ME/CFS (PEM (fatigue), sleep, and cognitive problems) were turning out to be the core symptoms in long COVID as well.

Early Long COVID vs ME/CFS

Three symptom categories distinguished the early long-COVID patients from people with ME/CFS: the high immune, neuroendocrine and orthostatic intolerance scores. Chest pain, irregular heartbeats, shortness of breath, fever, high temperature, night sweats, loss of appetite and weight change were all dramatically higher in the people with long COVID early in their illness. All of these could be associated with the “sickness response”.

As noted above, most of these symptoms declined rather dramatically over time, but a couple – all cardiovascular in nature (chest pain, shortness of breath, irregular heartbeat) remained significantly more troublesome in the long-COVID group

ME/CFS Group vs Long COVID

Whatever hope the long-COVID group could glean from some of the general symptom declines would have been dashed a bit, though, by looking to what might be in store for them in the ME/CFS group. If long COVID does indeed turn out to be ME/CFS, things were mostly not likely to get better, and in some cases might get worse. On the brighter side, things tended not to get much worse over time.

Sleep was worse in the ME/CFS group (ME/CFS / long-COVID at 5 months: 55-48) with unrefreshing sleep (74-62) being particularly problematic. PEM was worse in the ME/CFS patients but just by a bit (65-61). Cognitive problems worsened (46-39) but not dramatically. Immune symptoms were about 40% worse (28-20) but were not a major factor.

A few symptoms stood out. Flu symptoms; night sweats; hot/cold feelings; sensitivity to smells, light and noise; bloating; bladder issues; cold limbs; sore throats; and headaches were clearly much worse in the ME/CFS group. Many other symptoms tended to worsen in the ME/CFS group but many were not major symptoms and didn’t worsen significantly. On the bright side for the long-COVID group, orthostatic symptoms were reduced compared to the ME/CFS group.

Conclusion

Over time, long-COVID patients seem to be growing closer to ME/CFS.

Time will tell how this all plays out, but for right now, except for some cardiovascular symptoms that were expected to be heightened in the COVID-19 group, the long-COVID patients over time are looking more and more like people with ME/CFS. The same general symptom theme – PEM, fatigue, cognitive and sleep problems – is dominant in both diseases. PEM – the distinguishing factor in ME/CFS – is also the most prominent and troublesome factor in long COVID as well.

Some of the early symptoms of long COVID distinguished themselves from those found in the ME/CFS group, but they appeared to be mostly with an ongoing immune response, and most declined substantially over time.

The general merging of the symptoms of long COVID and ME/CFS appeared to be reminiscent of the early ME outbreaks. The outbreaks – which tended to be triggered by different pathogens – featured a disparity in symptoms in the early stages of the illness, which tended to resolve to a similar theme of fatigue, PEM, cognitive problems, etc.

If the long-COVID group does turn out to mimic the ME/CFS group, the long-COVID patients might be able to look forward to some reduction in orthostatic symptoms, but overall, some symptom worsening. On the bright side, while their symptoms may get worse, at least in general, they don’t appear likely to get much worse.

I was diagnosed with chronic fatigue around 2000. The last five years I’ve progressively gotten worse. Somehow I got COVID in January and apparently I now have long COVID on top of ME/CFS. I am just wondering if any of the studies had people that have both? At this point in time I am getting a bit afraid of remaining independent.

I was finally diagnosed in 1986, after becoming ill with mono in 1956 and never feeling well again. I was lucky though because through the years doctors never doubted me. Some doubted the tests that came back normal, one telling me “the tests are wrong.” Had many bouts of being bed bound then recovering to being house bound. Handful of hospitalizations, some to treat side effect of medicines well meaning doctors tried to help me by prescribing.

Again I was lucky. When I developed Covid in Dec 1999 (always the first to get what was going around) my NP rheumatology specialist immediately put me on antibiotic for pneumonia as preventative,antivirals, antifungal, vit D,vit C, vit A zinc, NAC and supported my declining primary care directive to go to hospital. Took months to recover, definitely became a Covid long hauler. Symptoms overlapped with MECFS symptoms in completely recognizing patterns. I’m sure there are more of us out there who have MECFS and after recovering from Covid 19 now are Covid long haulers too.

Darn autocorrect recognizable not recognizing patterns.

I got Covid 19 in December 2019, not 1999. Gotta love that Covid Fog. Is a darn nuisance though.

The only good news Patricia is that will all this money going to long COVID, hopefully both that and ME/CFS will get figured out. Hang in there!

I got suspected SARS-Cov-2 in March, 2020. Also have ME 20 years. Was very unwell. I unfortunately had severe allergy issues just prior to contracting the virus. Turned out I was eating things that I am allergic to, like mustard. Weight gain as a result. Then got virus before discovered what was happening. …..

I’m still recovering. Have had some progress over time and am on medications to aid some symptoms. Also nutritional supplements, vit D, antioxidants, B3, L- glutathione, … the list goes on. But at least I am improving. Up and down. Homeopathy as well- whatever thoughts are on this, it seems to be helping me. It’s a specific viral remedy for Covid.

My best wishes to you and all those affected by this. Let’s hope that something positive will come of all this and more research and help will be available to us. The medical profession will hopefully take this more seriously now. Best wishes.

Patricia, I found there are triggers that start downhill slides that seem to not end until you hit the bottom. The trick to stopping it is to see and follow Dr. Lapp’s advice w/maybe a few additional helps like NAC and he, and Dr. Campbell’s Library and classes. http://www.cfsselfhelp.org/library are key. Triggers, STRESS, OVERDOING IT and others. I read a statement that said, if you push past your energy envelope long enough and hard enough you can get to the point of no recovery. In part I think a surgery started my downhill slide coupled with a misdiagnosis by a specialist, followed by that physician’s very bad advice during a four month period of not being able to sleep (literally). Sleep had never been my issue. But suddenly I could not sleep. Dr.’s Peckerman and Cheney’s one sentence directive saved my life, sleep sitting up at the end of a couch or in a recliner and w/in a few days you will be able to sleep in your own bed, it worked like a charm. But the damage was done and it has taken me seven years to get over it. From experience I also believe their theory to be correct, it just needs to be proven. So though it worked like a charm, my brain and body sustained damage from four months of severe sleep deprivation, under the directive of a doctor! Secondly aging parents that needed more help, their subsequent death several years later, and not…let me repeat…not taking scheduled rests. A true rest is without a book, without music, TV etc., pure torture for the high powered types but it does make a difference and a clean diet with a few simple supplements, see Dr. Lapp’s website and see also Life Extension. We used to grow our own food, raise our own beef, and for the first time in years, this year we put in a garden, canning is too labor intensive, we purchased a vacuum pack sealer and bags free of bpa. If you have had mold exposure I am told that you can’t make headway with ME/CFS until it is dealt with, and nutritious clean food is key. Mold can be hidden for many years, example an improper window installation can cause water to trickle behind a wall, down a joist and under the flooring, rotting the subfloor undetected. Look for cracked drywall at window corners to floor and above to ceiling. If you have been exposed to Lyme, stay on Lemon and grapefruit extract and Stevia daily, Stevia at least three times daily with pure organic lemon juice. For Lyme see Why Can’t I (or We) Get Better by David Horowitz and also his YouTube video on Co-infections. Even if you don’t have Lyme you may find some helps or think of it this way, sharing is caring. Getting off sugar and gluten helped me immensely. But those 15 minutes of rest 3 to 4 times a day, irreplaceable. Of course there could be a multiplicity of contributing factors. Hopefully you can eliminate the root causes of the downhill slide and stop it or slow its progression down, shore up your system by rest and diet and let your body by God’s design do the rest, to heal itself. Perhaps you will be one that beats it! I am rooting for you!

http://treatcfsfm.org/menu-About-Us-2.html

http://www.cfsselfhelp.org/library/dr-lapp%27s-recommedations-supplements Hope this helps.

TY Judy. Let me just say that I do all that and then some 🙂

I had EBV in 1999 at age 45. It was so severe I was actually diagnosed with EBV meningitis along with hepatitis and pancreatitis. I semi recovered (I was an RN) and went back to work for 4 years until a severe back/neck injury. I have had multiple episodes of recurrent EBV proven with titers, including pneumonia and endocarditis. COVID is the straw that is trying to break this camel’s back but I won’t let it 🙂

I have had CFS for 31 years; half my life. I look at it like I’m the expert and please don’t tell me to get some exercise. I have a lot to offer the new long haulers. I would like to offer my experience to those who need it but I’m not sure how to do that. I can also participate in research.

As well, I’d like to suggest a new name for CFS patients that encompasses all those with post viral problems. Post viral disorder (PVD). It’s more inclusive and doesn’t just say “hey, I’m really tired”.

I like P.V.D. so much better than M.E. I have had this for eleven or so years now and am hoping that new studies since long covid will not only give us the hope of a solution with all the new research, but at least some recognition and understanding. I too could help advise long covid people. It takes practice to pace yourself …. when you have previously lived a very active life it’s hard to hold back and avoid P.E.M.

The only problem is that not everybody gets ME/CFS after an infection. There is an interesting twist to this though – some people can come down with COVID – not have any symptoms – and then get long COVID. That suggests more people might be in the post-infectious category in ME/CFS than we know.

Interesting.I thought i had mild case but had some racing heart issues.Now i am 13 months with this problem, low oxygen, fatigue, sleep apena, sore body parts, for months..Asthma has gotten worst..High heart Rate when up n doing any work ,even bathing etc..So post viral is worst for me..

I like the name you suggested, has a nice ring to it and easy to remember. Christmas eve 1994, 27 years ago I thought I had the flu but didn’t recover, eight months later I went to the doctor. Finally diagnosed late 2014/early 2015, by that time I couldn’t comprehend contracts, reading, writing checks, had lost a tremendous amount of vocabulary, and 30 points on my IQ! Hearing your pain, and disgust. My sister made the remark; you have been having issues for years and in her opinion the only thing I needed was exercise”. After giving my brothers girlfriend (a respiratory nurse) information before a planned visit, she kept insisting we go walk and exercise, (needed after driving two days w/out much sleep to get there) to top it off a trip to the mall, only she parked at the opposite end just before closing to make sure we had to walk the entire length and she set a fast pace to get to the store, then we were locked outside the building, I was out of gas before 1/8th of the way. At the time of onset I was in peak physical condition, and though pure torture, have not able to exercise since. The Feb. 2016 (YouTube) ME/CFS Grand Rounds video with the top ME/CFS experts sponsored by the CDC as a continuing Education piece held a shocking revelation for me; the highest percentage that is effected by ME/CFS are the top athletes and the second category are those in peak physical condition and/or that held high stress jobs. Perhaps that is why a number of medical students end up with ME/CFS and have devoted their time to the study of ME/CFS. And why my visits to the gym before doing a walk, run, ride with my two horses in the canyons followed by a brief swim before work every morning came to an abrupt end. Torturous also is the fact every good day brought the sense of “being well, over it, healed” only to find it is a never ending saga and ending up without having any ‘really good days’ (normal days) anymore. One physician was quoted last year during the Covid Pandemic as saying; He would rather have cancer than ME/CFS, because ME/CFS is a life sentence without parole. Though he is right, I purpose to live life as fully as possible, albeit at a much slower pace, still accomplishing, just in smaller increments, fighting discouragement more since I have finally realized that it just ain’t goin away, at least not in this lifetime without Divine intervention. I tested positive for 1 copy of MTHFR C667T followed by Lyme in 2015, blood sent to and tested by Armin Labs in Germany. Your sage advise is welcome. It has been a seven year climb from where I was, and just now able to research, write, though sometimes verbal communication becomes difficult. Pronunciation is becoming an issue, what’s up with that? I found Dr. Lapp’s site and library which is helpful. Signed, Been Through the Ringer But Still Hanging On.

I too have been using “Post Viral Syndrome” to describe my illness and Covid long haulers as well. The use of one term for these seemingly different illnesses might eventually lead to a paradigmatic shift in thought and theory with respect post-viral illnesses and hopefully we will see a more multi-disciplinary approach to diagnosis and treatment.

Agree. A name change is long overdue.

Thanks for the article.

Some of them definitely have orthostatic issues starting up. And that often takes a long time to start for me/cfs patients anyway. But this is good to hear, that the study result is so clear.

It’s been way over 6 months for some of the early long covid cases and some are starting to get diagnosed with me/cfs. I think it’s already time to call it what it is, the latest in a long series of me/cfs outbreaks.

This is pretty much what I expected.

Important to note is there will be a lot of people who actually have just Post Viral Fatigue Syndrome (PVFS) blurring this comparison, as we know most PVFS improves over time anyway.

I think 2 years out is when we will really start to see a near mirror overlap in those still with Long Covid symptoms and ME/CFS.

Also important to mention I think many new researchers to this area that have said “Long Covid is nothing like Chronic Fatigue Syndrome”, is actually because they have no idea what ME/CFS really is.

I blame that damn name ‘Chronic Fatigue Syndrome‘ again highlighting just then one symptom ‘fatigue’

A name that still is affecting research attitudes today.

Anyway when long Covid and ME/CFS patients finally merge as the same condition, we’ll see some red faced immune researchers and hopeful they’ll push ego to the side, join forces with ME/CFS researchers and help look for treatments!!

Absolutely. There are people in that group who are coming out of it and at some point will not have long COVID (or ME/CFS). They’re watering down the symptoms to some extent.

“Anyway when long Covid and ME/CFS patients finally merge as the same condition, we’ll see some red faced immune researchers and hopeful they’ll push ego to the side, join forces with ME/CFS researchers and help look for treatments!!”

🙂 🙂

Somewhere I saw Francis Collins, for the first time that I can remember, being a little defensive about the support the NIH has given ME/CFS. He said something to the effect that we are pouring resources in ME/CFS – we have 3 research centers and an intramural study: he neglected to mention how small those research studies were, how long that small (but intense) intramural study is taking and that they’re spending about $15 million/year on ME/CFS.

Hopefully at some point the NIH will have to answer some strong questions about their support of the million or so people with ME/CFS.

Honestly, not to put Collins on the spot so much. He’s one of the only ones to actually support us! It’s the culture of the NIH as a whole that’s the problem.

Hi,Cort, I always said that covid-19 is not alone,but they comes with immune dysfunctions and immune mediated inflammations. –that is really pointing to the ME/CFS.

We found that the severe case of ME/CFS showed up 3 yrs prior to

covid-19 pandemic. They had characteristically huge liver and sever

immune inflammations with occ.myocarditis.

The postcovid syndrome is in my opinion, ME/CFS.

It appears that I had Covid in December 2019. I was very I’ll for weeks and never quite recovered. I kept asking my doctor why I was so exhausted, dizzy and fuzzy brained. I did 1 dose of the J&J vaccine and it blew up my immune system (3/21).

I was barely able to walk and then was diagnosed with neurological issues, chronic fatigue and fibromyalgia.

I’ll have some reasonable days and then I’m down and out. Terrible depression. I cannot work or do much of anything I used to.

I did go for few weeks to a post covid clinic in my small local hospital. Very expensive and there was not much information at the time.

I’m following some diet, supplements and exercise protocols I’ve researched.

I’m a 78 year single woman living on social security and wonder if I’ll ever have my life back. So stressful.

I was dx with Pots and ME. Shortness of breath is one of my pesky symptoms and I ve never had covid-19.

Yep. Me too. Complete with low oxygen levels according to my O2 monitor. How on earth that wasn’t measured for ME/CFS patients escapes me.

I should clarify – I most likely HAVE had COVID, but recovered back to baseline with no issues (I assume because my MCAS supplements -vit d, high dose vit c, quercitin, zinc, etc…- are also what was recommended for COVID protection/treatment), but my low oxygen issues predated it.

Me also have shortness of breath at worse days. And also airhunger. I have ME/POTS.

Because me/cfs/long covid is basically histotoxic hypoxia

Poisoned cells can’t make use of o2 from blood.

Thanks Cort. So glad that published research comparing the two has commenced.

There may be an additional factor, besides the ongoing immune response, that might explain why some of the the early immune-neuroendocrine symptoms recede: symptom management. It takes months to accept the chronicity of one’s illness and to unlearn one’s drive to push through it. Perhaps the tamping down of those symptoms reflects the patient’s progress in finding competent medical practitioners and learning proper pacing strategies.

I’ve had post-infectious ME for seven years. In the early months of my onset and major setbacks the immune-endocrine symptoms are always prominent, especially flu-like malaise, sore throats, mouth sores, lymph nodes, chills, hot/cold feelings. These symptoms do seem to recede a bit over time but not completely. In fact, to this day they can re-emerge at any time if I overdo physical exercise, especially cardio. Only by pacing with a continuous heartrate monitor am I able to keep them more or less at bay.

So it seems like the early-late differences result from a combination of natural course and better symptom management. Perhaps it’s similar with long Covid.

Additional observation: It might be very interesting to add “wired and tired” as a symptom category in future studies. In my case, this is one symptom which was rarely present early on but became and remains a major nuisance years in, although POTS followed the same pattern for me (and I suspect the two are intertwined). Wired and tired is also a symptom, like PEM, that that’s very difficult to communicate to those who haven’t experienced it.

Such a key symptom for me at least. “Wired and tired” is another unusual symptom that one suspects could only come from the ME/CFS field. I’m surprised its not in there as it is so immediately evocative.

Absolutely spot-on….the curse of being exhausted…laying in bed wired..and remembering the past pleasure of the endorphin high…never more

Me too, PEM, brain fog and wired are tired are things that remain no matter how much I manage the rest. 3 very CFS symptoms. I have CFS and my partner now has long Covid, there are some similarities and some differences. They seem to be improving very very slowly. It will be interesting to see how the long Covid people do over a longer time span as many of us have years and years and as one of the comments here reflects – half their life.

Hi Alison,

Those same three are mainstays for me as well, in addition to sleep problems, which include but transcend Wired and Tired. In the past year, however, I’ve almost completely eliminated the brain fog.

There are probably many factors in my protocol that helped. But the one thing that seems to make the biggest difference is Pyridostigmine (Mestinon). I was able to get a prescription from my cardiologist because I have POTS. Originally, I expected it to alleviate orthostatic tachycardia and hopefully expand my physical exercise window. It did both of these things immediately. But I did not expect the Mestinon to completely eliminate migraines and significantly reduce brain fog and the unique headaches that accompany the fog, which it seems to have done after moving up to three small doses per day.

If you have POTS, or if you have an open-minded doc managing your ME, I strongly suggest trying Mestinon if you haven’t already.

Good point. I’m sure that symptom management, pacing, etc. is helping.

Looks like ‘help’ may be coming from an unexpected place.

‘Alexa’ and similars may be monitors for heart rate variability, for it can detect irregular heartbeats, as well as breathing patterns.”

Should, imo, then be capable of much more– in logging info and data – not just for researchers to ‘mine’– but for individual patient’s records/doctors/specialists.

article:

“Alexa, do I have an abnormal heart rhythm? UW researchers use AI and smart speakers to monitor irregular heartbeats

by Brian T. Horowitz | Mar 17, 2021 11:43am

and co- author :

Shyam Gollakota, a UW associate professor in the Paul G. Allen School of Computer Science & Engineering

found at:

https://www.fiercehealthcare.com/tech/alexa-do-i-have-abnormal-heart-rhythm-uw-researchers-use-ai-and-smart-speakers-to-monitor

From my experience, ME/CFS is “relapsing and remitting” and “progressive.” When I was diagnosed, Dr. Jain mentioned at some point it was relapsing and remitting like MS. Though that was 20 years ago.

The progressiveness of the disease is not something addressed very often (though, perhaps, hopefully, the course of that is different with early interventions or will be if we can nail a medicine that slows the progression)

Prompted by Dean Echenberg, I think Health Rising was the first to really look into the relapsing remitting group.

The results were surprising.

https://www.healthrising.org/blog/2015/04/20/disease-course-in-chronic-fatigue-syndrome-and-fibromyalgia-a-survey/

Cort, did you see this report on immunocompromised persons may not have antibodies after being vaccinated? Some taking immunosuppressive drugs show they need a third vaccine shot.

https://www.cbsnews.com/video/coronavirus-vaccine-immunosuppressive-medications/#x

I am so sad to read about this. Sad for having been ignored for all these years, having been mocked, called fakes, liars… All of a sudden, the faces of the people having had THE bug are everywhere. What about us? Weren’t we sick enough? Worthy enough? What an awful waste.

Such is life. In my experience, it’s only when things affect other people they actually take notice.

A month ago I learned about a local person, who had not recovered smell and taste after coming down with Covid-19. They DID recover smell and taste after receiving the vaccine (don’t know which one). Wonder if there is a study indicating that the vaccine is helping others with Long Covid. CDC: “MRNA vaccines teach our cells how to make a protein—or even just a piece of a protein—that triggers an immune response inside our bodies.” I have started attributing the recent significant lessoning of my ME/CFS symptoms to the Moderna vaccine I received. Still too soon to tell, as am very familiar with “works until it does not anymore” routine. However, I am really looking forward to booster vaccines if they become available.

There have been many reports of long-haulers feeling better after the second dose of MRNA vaccines. There was even some news coverage.

A family member of mine had suspected Covid. It was a mid case. She’s had multiple symptoms since then, including losing most, but not all, of her sense of smell. After her 2nd dose of a MRNA vaccine, many of her symptoms receded. Later, some came back. Some didn’t. Though she didn’t recover her sense of smell.

Here’s one of the news articles:

https://patch.com/new-york/portwashington/li-covid-advocate-spurs-yale-study-vaccinating-long-haulers

This article also mentions that a study on vaccine effect on long-haulers is recruiting patients.

Going to throw in a curveball, and most of you will think I’m nuts! But I’m not. Got CFS about 2000. Affected me since.

It got really bad about 7 years ago.

I am convinced that most if not all what are classed as neurological conditions are in fact demonic possession and/or demonic oppression. Not all, but some.

I’m wondering if the moderna helped me a little too. But I started taking supplements everyone recommends that I had long resisted (sooo many meds) at same time, and increased BP meds. So it’s hard to tell. I THINK having a little easier time with breathlessness and maybe orthostatic intolerance. But with very slight changes, pacing gets even more confusing for me. Speaking of breathing :), Does anyone have a good summary article to recommend about use-of-oxygen issues mentioned here and elsewhere? My pulmonologist is the most open and intellectually curious of all the many specialists Im trying to work with. But I’m not sure she gets the issue of oxygen not getting where it needs to go. Or how to respond to my reports that whenever I’ve had oxygen in the ER or hospital, it has helped me feel a little better, even though the oxygen intake measurements don’t seem to indicate a need. A good all-in-one article in the Oxygen issue would help. Another vote here for PVD. “ME” is awkward to say and spelling it out confuses people.

Hi Cort: Thanks for your piece on this article. You might want to check the Immune data over time in the table above as the correct numbers are below:

Immune 43.83 (22.90) 19.80 (17.93) 27.71 (16.68)ab

Lenny

Thanks Lenny. I accidentally transposed the line from above the Immune data into it. That did not change the conclusions in the blog – that the immune symptoms declined over time – as I was using the correct figures.

I think this study is interesting. I got covid and then long covid in march 2020 and I definitely think I had or was developing full Chronic fatigue/ M.E. I was worried if I didn’t get it under control I was going to have it with me for years. I started doing tons of research and doing whatever I could to pull myself out of long covid. It eventually worked and I am 95% recovered hoping to start jogging again. I wrote my full story on my website and what I did to recover if it can help anyone. http://madebydanica.co.uk/my-7-steps-to-long-covid-recovery/