Geoff’s Translations

The GIST

Andreas Goebel Ph.D. has been on the hunt for an autoimmune cause of chronic pain since he observed high levels of post-infectious antibodies in his patients.

Redefining Chronic Pain

Andreas Goebel of the Pain Research Institute at the University of Liverpool has been trying to redefine how we think about chronic pain for about 20 years. His journey began with a 2010 complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) paper, which proposed that an autoimmune subgroup was present, included studies suggesting that immune treatments such as plasmapheresis and IVIG are helpful in CRPS, and most recently found that the transfer of IgG serum from fibromyalgia patients into mice replicated most of the FM symptoms in the mice.

Since then, several studies have found that passive transfer of serum from ME/CFS or long-COVID patients into mice or culture has replicated the symptoms or findings in those diseases.

This year, Goebel asked, in “Fibromyalgia syndrome—am I an autoimmune condition?“, the $64,000 question. It’s been asked before – repeatedly in ME/CFS, in particular, but more recently in fibromyalgia (FM) – and still we have no clear answer.

It seems strange that such a fundamental category – autoimmune disease – still has so much grayness to it. Maybe it’s just the nature of our complex immune system to not fit easily into boxes, or maybe the grayness, at least in part, is being driven by diseases like fibromyalgia, ME/CFS and long COVID which seem to defy traditional categorizations and are slowly tearing them apart.

The GIST

- Andreas Goebel, PhD, has been trying to redefine how we think about chronic pain for about 20 years. His journey began with a 2010 complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) paper which asserted that an autoimmune subset was present.

- This year, Goebel asked, in “Fibromyalgia syndrome—am I an autoimmune condition?“, the $64,000 question. It’s been asked before – repeatedly in ME/CFS, in particular, but more recently in fibromyalgia (FM) – and still we have no clear answer.

- In a way, that’s not so surprising. Autoimmunity is a complex and sometimes controversial topic. Back in the 60’s, the definition of autoimmunity was pretty clear; find the offending autoantibody (antibody that attacks the tissues), replicate the disease in an animal model, and then treat the disease by eliminating it.

- That definition was discarded about 30 years ago, in favor of a less stringent definition that considers the broad body of evidence, does not require the identification of an autoantigen, and asserts that replicating the disease in an animal by transferring antibodies is sufficient.

- Recently, Goebels has shown that giving antibodies—the substance of autoimmunity —to mice from fibromyalgia patients caused the mice to exhibit symptoms similar to those of fibromyalgia patients. Since then, similar studies have found the same to be true in ME/CFS and long COVID.

- For Goebel, that’s enough – he believes fibromyalgia is an autoimmune disease that’s probably best treated by immune drugs.

- Goebel didn’t just replicate FM in mice – he tracked down what the antibodies from the fibromyalgia patients were doing to them. He found that the antibodies congregated around a central sensory hub in the body, known as the dorsal root ganglia. Found just outside the spinal cord, all the sensory signals coming from the body go through the dorsal root ganglia.

- The antibodies were concentrated on what are called “satellite glial cells,” which bear some resemblance to the microglial cells found in the brain. These cells protect, support, supply nutrients to, remove waste products from, and sometimes excite the cell bodies of sensory neurons – causing pain. Hyperactive glial cells are believed to play a major role in chronic pain.

- Goebel’s study, then, suggested that an autoimmune reaction was sending the satellite glial cells into a tizzy, potentially producing the hypersensitivity to pain found in FM.

- A followup study replicated most of Goebel’s findings and demonstrated that the conception of FM as a purely central nervous system disease is outdated. For instance, something called “central pain inhibition (CPI) ” – which concerns the ability of the central nervous system to inhibit pain levels – was not affected at all by the antibodies.

- These findings suggest why central nervous system drugs used in FM, such as Lyrica, Cymbalta, and Gabapentin, can be so ineffective at times. These researchers believe that a large subset of FM patients will benefit from drugs that affect the immune system in the periphery (the body) – not the central nervous system.

- A respected rheumatologist, Daniel Clauw, has pooh-poohed the autoimmune connection, saying FM looks nothing like autoimmune disease, does not respond to autoimmune drugs, and doesn’t exhibit the high levels of inflammation typical in autoimmune diseases. He dismissed the IgG transfer study results and believes FM is, at heart, a central nervous system disease.

- The autoimmune/central nervous system conceptions of FM and similar diseases have vast repercussions for them. An autoimmune conception of these diseases opens the door to one set of treatments, while a central nervous system conception opens the door to a mostly different set.

- If one were to pick one, given the many more options available, one might choose FM to be an autoimmune disease. Indeed, many immune-modulating drugs – some of which can also affect the central nervous system – are being trialed in long COVID. Ultimately, the question of whether FM is an autoimmune disease may be answered more quickly by the results of treatment trials in similar diseases.

A Short History of Autoimmunity

More than 80 kinds of recognized autoimmune conditions exist, and some researchers count up to 105. Despite all the studies (actually because of them), no consensus exists on exactly what constitutes an autoimmune illness. Disagreements on whether autoantibodies are driving autoimmune diseases, or are simply present, are not uncommon.

Progress in the medical field usually results in more precise definitions, but just the opposite has happened in autoimmunity. Instead of making autoimmunity more exclusive, Rose and Bona’s 1993 definition of autoimmunity opened up the criteria for it.

Finding a specific autoantibody that replicates disease is no longer a requirement for autoimmunity.

Wibetsky’s 1957 postulates had required that free circulating antibodies, a specific autoantigen that produced the same antibodies in animals, and specific physical changes be present.

Over time, though, Wibersky proved to be too restrictive. Rose and Bona asserted that, instead of requiring specific changes, researchers should examine the general body of evidence. The emphasis on identifying the autoantigens causing the problem was dropped.

Instead, a far simpler test case consisting of direct, indirect, and circumstantial evidence was proposed. They argued that the most compelling case for an autoimmune disorder (direct evidence) occurs when transferring an immune factor – like IgG antibodies or T-cells – into another human, animal, or culture, causes evidence of the disease in them. Next comes indirect evidence, which involved producing the same result in another animal using a specific autoantigen. Finally comes circumstantial evidence, such as finding autoantibodies, white blood cells infiltrating tissues, and a positive response to a drug.

ME/CFS – A Little History

After finding high levels of some autoantibodies, Klein and Berg, thirty years ago, proposed that ME/CFS (chronic fatigue syndrome) was a “psycho-neuro-endocrinological autoimmune disorder“. The next year, after Konstantinov et al. found increased levels of autoantibodies to nuclear envelope proteins, they proposed they had uncovered an “autoimmune component” in ME/CFS. The very next year, a high frequency of autoantibodies to insoluble cellular antigens was suggested to differentiate ME/CFS from other “rheumatic autoimmune diseases“.

More recently, a 2018 article from Euromene, “Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome – Evidence for an autoimmune disease“, stated, “there is convincing evidence that in at least a subset of patients ME/CFS has an autoimmune etiology.”

That same year, stating, “we think that a solid understanding of ME/CFS pathogenesis is emerging”, Blomberg et al. proposed that an infection initiates an autoreactive process in the B-cells in ME/CFS, fibromyalgia, and similar diseases.

Fibromyalgia – A Little History

On the fibromyalgia side, after finding high levels of anti-DFS70 antibodies, a 2019 Korean study proposed it may have found a “biomarker for differentiating between FM and other autoimmune diseases”.

By 2021, Martinez Lavin was asking, “Is fibromyalgia an autoimmune disorder?“, and in 2022, Shoenfeld was so convinced that FM, ME/CFS, etc., were autoimmune that he proposed a new entity called “autoimmune autonomic dysfunction syndromes” be created.

Things got so controversial that last year Shoenfeld and Daniel Clauw publicly debated the autoimmune question in, “Is fibromyalgia an autoimmune disorder?“. Meanwhile, also last year, Italian researchers proposed in “Inflammation, Autoimmunity, and Infection in Fibromyalgia: A Narrative Review” that FM is probably an immune-driven and often post-infectious disease.

Fibromyalgia – Are You an Autoimmune Condition”?

This year, with some new findings under his belt, Goebel asked, “Fibromyalgia syndrome—am I an autoimmune condition?”

Antibody transfer experiments largely replicated fibromyalgia in mice.

According to Goebel, Rose, and Bona’s model provides strong evidence that fibromyalgia is an autoimmune disorder. Antibody transfer studies that have replicated symptoms in animals or produced changes in culture in FM (as well as ME/CFS and long COVID) provide direct evidence that autoimmunity is present.

Following his successful antibody transfer studies in complex regional pain syndrome, Goebel found that transferring IgG from UK and Swedish FM patients resulted in increased pain sensitivity, reduced grip strength, reduced activity, and mild damage to small nerve fibers.

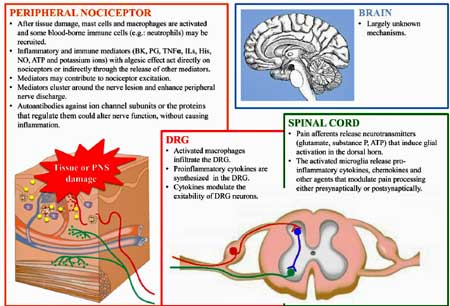

Digging deeper, Goebel’s team found that the IgG antibodies from the FM patients were clustered on and presumably attacking the dorsal root ganglia (DRG) – the bundle of sensory neurons located just outside of the spinal cord through which the signals from the body flow. If you want to dysregulate pain signals from the entire body, the DRG would be the first place you might want to attack.

Glial Cells Implicated

Satellite glial cells under attack (A=normal; B-abnormal) in a form of ataxia (Image by Hanani; Wikimedia Commons)

It got better – the IgG antibodies congregated on the satellite glial cells found on the dorsal root ganglia. These glial cells – which have some similarities to microglial cells in the brain – protect, support, supply nutrients to, remove waste products from, and sometimes excite the cell bodies of sensory neurons – causing pain. Hyperactive glial cells are considered to play major roles in chronic pain, and efforts are underway to find ways to calm them down.

Critically, no IgG antibodies were found in the spinal cord or brains of the mice given the FM IgG. This is presumably a good finding as it suggests that getting drugs to these protected areas may not be necessary.

The next FM IgG transfer study largely supported Goebel’s findings. Using an “optimized protocol” and a much larger Canadian and Swedish fibromyalgia cohort, Camilla Svensson’s lab found that the degree of IgG binding to cultured SGCs correlated moderately with the patients’ pain intensities.

Directly looking for anti-satellite glial cell antibodies, she found they were associated with increased pain but that only the severe FM group had significantly elevated anti-SGC antibodies compared the mild FM group and healthy controls. She concluded:

“pathogenic autoantibodies either underlie FM in a subgroup of patients or are present at concentrations too low to be detected in our assays in individuals with mild disease.”

Noting that 60% of FM patients have small fiber neuropathy (and 40% don’t), she suggested that “multiple overlapping disease mechanisms,” including high anti-SGC antibodies in some patients, are likely contributing to FM.

Svensson’s findings suggest that the conception of FM as a purely central nervous system disease is outdated. For instance, something called “central pain inhibition (CPI) ” – which concerns the ability of the central nervous system to inhibit pain levels – was not affected at all by the antibodies. Indeed, FM studies indicate problems with central pain inhibition play a role in some FM patients but not others; i.e., not all the pain in FM may be driven by problems in the brain.

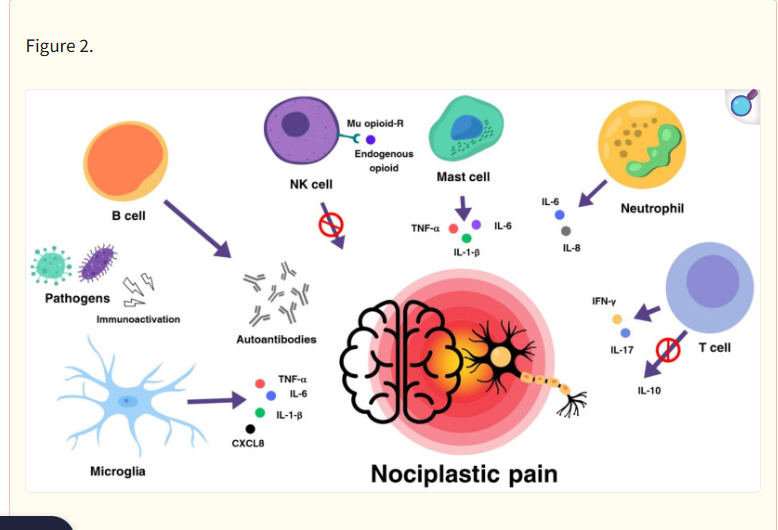

An Immune model of nociplastic pain (by Parolli, 2024)

Goebel’s and Svensson’s findings suggest why central nervous system drugs used in FM, such as Lyrica, Cymbalta, and Gabapentin, can be so ineffective at times. They believe that a large subset of FM patients will benefit from drugs that affect the immune system in the periphery (the body) – not the central nervous system.

Indeed, evidence of immune dysregulation in FM continues to emerge. Verma’s 2022 Canadian study uncovered hyperactivated but exhausted immune cells and natural killer cells. These cells appear to be turning on macrophages which then attack the small nerve fibers.

The authors proposed that the peripheral nerves in FM are chronically expressing factors that draw the NK cells to attack them. Their idea that a chronic or latent infection of the nerves or an IgG-initiated upregulation of the sensory nerves brings FM, after decades of focus on the central nervous system, closer to the current conceptions of ME/CFS and long COVID.

Inflammation, Autoimmunity, FM and ME/CFS

On the other hand, the fact that large amounts of systemic inflammation are not present in FM, ME/CFS, and similar diseases suggests that these conditions are not autoimmune disorders. Some autoimmune diseases, however, do produce localized inflammation, and Goebels argues that localized inflammation of the sensory nerves in FM is driving the disease.

Daniel Clauw, a rheumatologist and prominent FM researcher, has pooh-poohed the autoimmune connection, saying FM looks nothing like autoimmune disease. He has relayed that FM appears to be an oddball disease to rheumatologists, who mainly treat autoimmune diseases, and noted that the FM autoimmune charge is not led by people who treat autoimmune diseases.

While Clauw agrees that “sub-clinical inflammation” is present in FM, he notes that it’s not comparable to the systemic inflammation found in autoimmune disorders, and that neither anti-inflammatory nor autoimmune drugs used to treat autoimmune disorders are effective. Additionally, no tissue damage has been found that should be caused by an autoimmune attack.

With regard to the studies showing that serum from fibromyalgia largely replicates the disease in animals, Clauw reports that this process has rarely been found in “acknowledged autoimmune disorders” and doesn’t believe a good FM animal model is present, anyway.

Clauw may agree that localized inflammation may be present, but he clearly objects to characterizing FM as an autoimmune disease. Indeed, he believes that doing so makes a mockery of the term. Clauw believes FM is still best understood as a central nervous system disorder.

Treatment

The immune/autoimmune/central nervous system conceptions of FM and similar diseases have vast repercussions for them. An autoimmune conception of these diseases opens the door to one set of treatments, while a central nervous system conception opens the door to a mostly different set.

Goebel does not, in his short paper, discuss which drugs might be helpful in FM. While Clauw does not find autoimmune drugs useful, he does leave the door open for peripherally acting immune drugs like interleukin-6 (IL-6) and Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors.

Goebel believes IVIG can effectively treat some cases of chronic pain,

Verma (who also participated in Goebel’s paper) suggests that elevated levels of anti-SGC IgG could identify FM patients who might benefit from B-cell-depleting drugs, IVIG, or plasmapheresis. IVIG was the most efficacious treatment found in a recent large ME/CFS survey. In a pilot study, a different B-cell depleter, daratumumab, proved very effective in about half of ME/CFS patients.

That’s probably no surprise to Goebel, who, way back in 2010, proposed in “Immunoglobulin responsive chronic pain” that IVIG would be helpful in some chronic pain conditions. In a 2008 trial, IVIG (400 mg/kg daily for 5 days) reduced pain and tenderness and improved strength in FM patients with small fiber neuropathy (demyelinating polyneuropathy). A very small (n=7) 2020 IVIG trial found that IVIG improved FM symptoms and small fiber neuropathy as well.

We’re at the tip of the iceberg in understanding what role immune modulators will play in these diseases. If Goebel is right, they’ll play a major role in treating it. If Clauw is right, they won’t.

All in all, we should probably hope that Goebel is correct, as the number of immune-affected drug possibilities and trials far exceeds those focused on the central nervous system.

While some treatments span categories (rapamycin, besizterim, sipavibart, low dose naltrexone), current central nervous system trials in these diseases are focused mostly on rather tired antidepressant, brain stimulation and mind/body approaches. Ketamine, psilocybin and tFUS bring some new approaches, however.

https://www.healthrising.org/blog/2025/06/22/neuroinflammation-tfus-jarred_younger/

A much larger array of immune-modulating or antiviral drugs is being tested, mostly in long COVID. They include baricitinib, rapamycin, daratumumab, IVIG, plasmapheresis/immunoadsorption, sipavibart, bezisterim, leronlimab, maraviroc, Ensitrelvir, remdesivir, tocilizumab, etanercept, rovunaptabin, Rituximab, and others.

With quite a few drug trials underway, long COVID – the symptomatic sister to both ME/CFS and FM – will help our understanding of all of them.

So, in some ways, we’re back to where we started. Neither FM nor ME/CFS nor long COVID fit traditional illness categories. Fibromyalgia has never fit well into the rheumatological camp – something that some rheumatologists have made clear to their FM patients for a long time – and (as evidenced by their lack of a home at the NIH) ME/CFS and long COVID don’t fit anywhere either. Either the traditional illness categories need to be stretched or reimagined to accommodate these diseases or new categories of illness need to be found.

- Coming up next: Digging deeper – the IgG antibody connection resolved?

@cort I have to go spinal surgery and I don’t have money.all money gone in tests

If you want I will send you proóf.please hel me

.

Anish I wish I could help but I don’t have nearly the funds necessary to make a difference. Have you thought of creating a fundraising drive. If you look on the internet there are also some non-profits that help people cover the costs of medical treatment. I don’t know if they would be helpful or not. Good luck with your search!

Cort, can you do a post about this?

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41591-025-03788-3

Since I have been researching ME/CFS, something that I see that keeps coming over and over it’s the microbiome.

I really hope that’s the culprit of the disease.

Not exactly on topic, but it looks like I’m about to be diagnosed with adult onset of a genetic neuromuscular condition called myotonia congenita.

While reading about myotonia congenita, I noticed several articles describing how it has been misdiagnosed as fibromyalgia.

So if you have fibromyalgia, it might be worth reading about myotonia congenita to see whether the symptoms ring a bell.

Hi Sarah T, I just did look up myotonia congenital and was surprised that most of the symptoms listed (except the ‘athletic appearance because of muscle development’ apply to me. Scoliosis, lazy eye, myotonia, pain, small fiber neuropathy etc. yet I have Ehlers-Danlos (also genetic) instead. Interesting that one of the first presenting symptoms of some forms of EDS are being a ‘floppy baby.’

All this makes me wonder how many people have a ‘something else’ which is too rare or requires too many exotic tests to discover–and why there seem to be so many sub-categories in fibromyalgia or ME/CFS. Because they are so rare, few people study them and even fewer doctors (covered by insurance especially) are willing to experiment with untested treatments. That leaves a lot of us frustrated. I do wish you luck in your own health journey.

That’s interesting.

The enlarged muscles don’t happen in every MC patient, by the way. Also, the myotonia doesn’t always show up in an obvious way and may only be detected by electromyography (EMG) testing, and sometimes not even then.

The name is misleading because the condition was described many years before genetic testing, and was named after what was observable at the time.

People say that naming conditions after the main symptoms is best, but if it’s named after the discovering doctors that gives more flexibility as our understanding grows.

I have seen some articles recently about introducing more genetic testing for babies. Usually it mentions testing for 200 common genetic conditions. I think this would save a great deal of heartache and delayed (or never reached) diagnoses. I hope they include the known ones for EDS in there.

Cheers,

Sarah

The problem with naming these diseases is that each individual is a sub-category unto themselves and here we come to the idea of personalized medicine. Remember when breast cancer was thought to be just one malady? Now it is divided into many subclassifications.

I think AI to be used in medicine might be very helpful to ferret out all these sub-classifications because rare is the doctor who knows about all of common and less known genetic conditions. And developed conditions too! You have hinted that you know that the most common form of EDS, Hypermobile, has no diagnostic test. Even so, most PCPs, the gatekeepers of treatment, think that disorders like EDS are so rare as to often rule them out in the beginning regardless. “When you hear hoofbeats, think horses not zebras” they are taught.

I guess research just needs to continue so we understand better. Too bad that in the current political climate that is being hindered, but with most things, ‘this too shall pass.’ I hope.

Also, just be careful when researching it – it’s “myotonia congenita”, all in Latin. There are other conditions that have the English word “congenital” and “myotonia” in them, and search engines and even scholarly articles and databases get them confused. And these other ones are life limiting or progressive, so you can accidentally give yourself a scare by reading about the wrong one, or reading an article that has conflated them.

I also noted that a condition called myotonic dystrophy was reported as being misdiagnosed as fibromyalgia.

Here is an article from the Myotonic Dystrophy Foundation (USA) summarising research on patients’ diagnostic travails:

https://www.myotonic.org/diagnostic-odyssey-patients-myotonic-dystrophy-journal-neurology-2013

According to Professor Novak, some patients with OCHOS have a localised autoimmune effect causing the cerebral arterioles to constrict abnormally. I don’t think he knows yet how this is happening, because cerebral arterioles cannot be imaged in a living patient and vasoconstrion and vasodilation in blood vessels in the brain are controlled by various mechanisms.

I have this suspected autoimmune OCHOS type and am being treated with vasodilators (partial improvement sustained for two years) and DMARDs (too soon to tell).

Dr Blitshteyn mentioned recently that traditional DMARDs are worth exploring because they are much easier to access than the various immune treatments mentioned in this article. One downside is that they take a long time to work, anything from three months to a year, so studies take a long time and trying them out as an individual patient takes some patience.

Thanks, Sarah. I didn’t know Novak had found that! I need to look him up again.

DMARDS sound interesting: Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) are prescription medications that calm down your immune system when it’s overly active. Healthcare providers sometimes call DMARDS antirheumatic drugs or disease-modifying drugs.

Good luck with both treatments 🙂

Cort – my entire one and only treatment for my ME/CFS/FM/Sarcoidosis since being bed-bound for a year in 2012, has been a DMARD (methotrexate) in a very low dose of one 2.6mg every Thursday. It was prescribed by my retina/sarcoid uveitis doctor, and over the years I’ve been able to live almost normally with the usual issues of Post Exertional Malaise and a need to PACE myself in order to reduce flares or crashes. The main issues with the medication were having reduced protection against viruses, etc., some mouth sores and some hair loss.

I always believed the DMARD was lowering my inflammation everywhere.

The pandemic period was difficult and quite confining . This past year I was diagnosed with Sjogren’s Syndrome and osteoarthritis, so I do think there’s a connection to autoimmune illnesses on some level.

One challenge is that the various medical specialists don’t want to be in charge of all the symptoms, so it’s really been up to me to learn as much as possible myself (Health Rising has been a very good source of information) and decide what I can do to have a quiet, fulfilling life without any group activity outside my home. I have no car, I order groceries to be delivered and have a garden to look at from my porch.

In Jan of this year, I decided to stop taking methotrexate since most co-morbidities had quieted down, and it’s such a strong old cancer drug. I wanted to see what I’d be like without it. That’s 6 mos ago, and so far I’m doing quite well, although the Sjogrens is a new nuisance, the arthritis is a pain in my toes, I still have sensitivity to smells and light and I still must pace myself, but most of my systems are relatively quiet. I do need a caregiver every other day to fill in the energy gaps for me, keep me from falling and drive me to appts and such. Most doctors are a little bit interested, some are skeptical, and most feel restricted by the sensitivities, lack of biomarker, inability to see my condition. Most say I’m “fine based on my good blood lab results.”

Hello Barb,

I’m trying out methotrexate at the moment. I don’t have ME/CFS but have longstanding mental and physical fatigue from what turned out to be an orthostatic intolerance syndrome (OCHOS).

I’m only a few months in but I think it is working. I was very interested to read of your experiences. I too hope that I won’t have to take it forever, although I will if needed. The blood tests are a bit of a drag and I would rather stay home quietly and look at my garden too.

Sarah T – The methotrexate does tend to settle down, which is nice.

Be sure to take L-Methylfolate (except not the SAME DAY AS METHOTREXATE) because it tends to lower the amount of Folate in your body, which you need for energy.

I’m curious about all the mentions of Herpes Simplex virus and its association with ME/CFS/FM. I am 80 but had that for years before getting ME. Should I take Acyclovir now as a mild replacement for the methotrexate ? Is that why I got ME/CFS/FM in the first place? A doctor at the Mayo Clinic told me it all started with PTSD lodged in my cell memory since childhood.

I think he stated it in a lecture rather than a publication. One of his lectures for Dysautonomia International had terrible sound quality and they didn’t end up publishing it on Vimeo or YouTube.

I have the details somewhere that I typed out after some laborious relistening. Let me know if you would like to have them and I can email a document.

Sarah, I find your reply interesting. I’m a patient at Stanford who was checked for suspected OCHOS but didn’t quite meet criteria. Currently my diagnosis is MCAS, ME/CFS, Long Covid, and Pure Autonomic Failure (which isn’t autoimmune). My dominant symptoms have been orthostatic chest pain, and lightheadedness/brain fog without a consistent drop in blood pressure.

2 observations in my personal situation: 1: Steroids always make me feel great until they wear off, which kind of supports the autoimmune concept.

2: My chest pain, but not the brain symptoms, have been substantially reduced since I started Amlodipine, which is a Calcium Channel blocker vasodilator that doesn’t cross the blood brain barrier. I would like to see if my doctor will consider switching me to one that does cross the BBB to see if it helps my brain symptoms.

Which vasodilator has helped your brain symptoms?

Hello Rondo!

Yes, I felt great on steroids too. I was given prednisolone tablets for a rash and was astonished to find myself “cured” for a week while taking them and in partial remission for three months afterwards. Also, one symptom disappeared and never came back.

Unfortunately I couldn’t continue with the steroids, but after a lot of detective work I realised my symptoms were consistent with OCHOS and started amlodipine. That also had a magic effect.

I wish I could say that that was my happy ending, but despite trying various doses and combinations of vasodilators, I have not been able to tolerate a large enough dose to get back to feeling normal. For instance, after a week at a normal dose of amlodipine I stop sleeping altogether. I do definitely feel a benefit from the smaller dose.

All the vasodilators I have tried seem to help, but each time I run up against a limit. Very frustrating.

Is nimodipine the one that crosses the BBB? I did try that last year, but the side effects defeated me. I have read of quite a few people taking it successfully.

Do they do Doppler ultrasound at Stanford to check the blood flow? I tried to get that here in Australia but it fell through. I am keen to try out the Lumia Health earpiece if it ever makes it here.

Right now I have stopped experimenting with vasodilators (just sticking with a small dose that works) and am working on DMARDs. Hydroxychloroquine didn’t seem to have any effect, so now I’m trying methotrexate. Too soon to say yet, but I have noticed a few evenings when I am feeling brighter.

Cheers,

Sarah

By the way, because I couldn’t get the Doppler ultrasound scan, my diagnosis is based on the fact that OCHOS is the only orthostatic intolerance syndrome known to respond to vasodilators.

Sarah, Thank you for your reply! Sorry it’s taken me so long to get back to you.

Yes, Nimodipine does cross the blood brain barrier. In fact most dihydropyridine CCB’s do, except for Amlodipine.

And yes, I was able to get the TC Doppler at Stanford. It was quite a process. My autonomic neurologist doesn’t do this test very often, so he outsourced its interpretation, and it took months to get the results. I was told I didn’t meet criteria for OCHOS diagnosis because the CBFv didn’t drop quite enough during the tilt. However, it clearly was abnormal compared to the controls in the papers I’ve read from Novak and others. It was frustrating not being able to ask directly about my results because the person who interpreted my test wasn’t available and my doctor said he wasn’t qualified to comment on them in detail.

Eventually I was diagnosed with post Covid ME/CFS which kind on explains all my symptoms anyway, so the matter was dropped.

Nothing has substantially helped my orthostatic brain dysfunction, which I call my Zombie Attacks. The only way I can control them is to get flat until my brain clears.

The reason I am still pursuing it is that my electrophysiologist started me on Amlodipine hoping to improve my orthostatic chest pain. It did, but it’s done nothing for my brain symptoms. So I’m hoping to get my autonomic doc, whom I see soon, to try switching me to a brain-penetrant CCB. He listens to me very well, but I wanted to be as informed as possible before I ask him about it.

I’m intrigued by your comment that the “only thing that responds to vasodilators is OCHOS”. Is there a reference or source that you know of for that concept? Is it something your doctor told you?

It does seem counterintuitive to give someone thought to have orthostatic blood pooling a vasodilator (amlodipine), but it seemed to help me a lot more than the midodrine.

I’m further intrigued by your trial and success with DMARDs. I have a history of rheumatic disease, mostly now in remission, but do I still get random joint pains. My ME/CFS doc recently started me on low dose Colchicine, and It seems to be helping the joint pain and I possibly also the chest pain.

Hello Coral,

Nice to hear back from you! I’m sorry your Doppler ultrasound test was inconclusive and that you couldn’t discuss the results directly. I would agree with you that any drop in CBFv below that found in the control group is significant.

It is interesting that amlodipine has helped you with orthostatic chest pain but not brain fog. I think you have a valid point to ask whether a different type of vasodilator such as nimodipine would work better, especially if you are taking the maximum dose of amlodipine.

You have probably read of a small number of people with ME/CFS who did very well on nimodipine. Sadly there has never been a trial or even a case study written up, but you can find links to the information posted by patients themselves on the Phoenix Rising forum.

I don’t have a specific reference stating that “my” subtype of OCHOS is the only orthostatic intolerance syndrome that responds to vasodilators, but if you look through a list of of the other OI syndromes, they are all treated with vasoconstrictors and volume expansion (or volume repositioning), and vasodilators are actually contraindicated because they would encourage blood pooling in the lower body.

In Dr Novak’s paper, he identified two subtypes of OCHOS, but unfortunately didn’t name them. One type is similar to all the other OI syndromes in that it involves blood pooling, low blood volume and lack of venous return, and responds to the standard treatments. The problem there is “not enough blood getting to the head” so the treatments try to counteract that.

Any “my” type is unique in that plenty of blood gets to the head but it can’t get in due to the hypothesised abnormal arteriolar vasoconstriction. And that can be be treated or at least improved by a vasodilator.

The thing would be to try to work out which problem you have (maybe it’s possible to have both?) – pooling in the lower body or constriction at the entrance to the brain. Or even something else.

If you can manage it, reading Dr Novak’s papers, having a look at his textbook “Autonomic Testing” (try through library), and watching this video (unfortunately sound quality is not great) might be useful.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DnIfvBzQLdw

Unfortunately, the lecture in which he said he suspected that the vasconstriction type of OCHOS is autoimmune never got published due to even worse sound quality. It was from the Dysautonomia International conference a few years ago. (He didn’t give much detail, just made that comment and moved on to the next topic.)

I hope the colchicine goes well.

Hope this makes sense. I am a bit tired today and my fingers type faster than my brain sometimes. You can find me at the Phoenix Rising forum if you would like to chat – just look for the person who mentions OCHOS all the time!

Cheers,

Sarah

Hi Sarah.

Thanks for your insight. I actually pulled out the raw data from my Doppler ultrasound test. I can’t verify this with a qualified clinician (I’m only a veterinarian:) but it looks like the reason I didn’t meet criteria is that my CBFv didn’t drop much until the 11th minute, and Novak’s published criteria only consider minutes 1, 5 and 10 post-tilt.

I’m not sure if I mentioned it, but I have a diagnosis of Pure Autonomic Failure, considered rare, on the basis of positive skin biopsy (they look for Lewy Bodies in the peripheral autonomic nerves) and positive cardiac MIBG scan (I have loss of sympathetic nerve supply to the heart). Most people with PAF have easily demonstrable orthostatic hypotension, which explains the brain symptoms, but I don’t have this consistently, so my case is considered atypical. The salt loading, compression stockings and hydration help a little. I was on Midodrine for several months and I think it helped, but maybe more of a placebo effect because I don’t feel any worse after stopping it. I stopped it because while it did increase my blood pressure (by tightening blood vessels), it also seemed to cause my already low heart rate to go even lower, worsening my symptoms.

They also think I have MCAS, which perhaps supports this autoimmune subtype of OCHOS.

Thanks for the Youtube link. I don’t think I’ve seen this particular video. Dr Novak’s accent is hard to interpret in a video, but it’s worth the effort. I think I saw the DI conference you mentioned. Couldn’t hear anything and they didn’t have subtitles.

It’s interesting about the vasoconstriction. For me it makes sense because my orthostatic brain symptoms often come on suddenly after a period of upright activity when I’m feeling otherwise okay.. It feels like a reflex. I call them my Zombie Attacks. I have to lie down to get rid of them.

Dr Novak’s textbook is on Google Books.

I see my autonomic neurologist next week so I will see what he thinks.

Also, just a question from a layperson:

Does autoimmune activity have to cause inflammation? What if the autoantobodies just glom up some receptors or get in the way of normal function of a bodily process?

Great question! I looked it up using AI Perplexity. It states that autoimmunity almost always leads to inflammation. In some cases it can be localized but generally it is systemic. That said, autoantibodies can serve functional purposes, and while those autoantibodies can produce inflammation sometimes they can just gum the works, as you note, by modulating the activity of the receptors on our cells.

I’m confused. If CFS doesn’t present with inflammation and isn’t auto-immune, why does an anti-inflammatory/reduced toxin diet help so much with it. I thought CFS WAS auto-immune triggered.

CFS has a clear history for Neuroinflammation in a subset of patients. Further, if you change your diet, it can also change how immune cells communicate and thus b-cells maybe have a reduced outoput of GPCR Autoantibodies, which are typical in ME/CFS. So there is inflammation (in the CNS) and there is autoimmunity in a subset of patients at least.

I absolutely love this question. This is the way my body has felt all my life.

Dr Blair Grubb at University of Toledo prescribed me Plaquenil for POTS that I developed 4 years ago after COVID vaccine. It’s been two months. He said we will evaluate at 3 months and may increase the dose. He started me low and slow at 100mg. He believes POTS is autoimmune. He said he is educating himself on the newer anti rejection drugs as he was on the transplant team when he started practicing and then pediatric cardiology. I feel grateful that I’m able to see him as he’s the only autonomic physician near me.

Grubb is an impressive guy. I remember him talking about autoimmunity and using more powerful immune drugs a couple of years ago at a Dysautonomia International conference. Good luck!

This is so interesting to read! I feel like many of us that are reading these articles are falling into those “gray areas” mentioned. If this is helpful to anyone else …. I have CFS with POS. I test positive for mono and have all the indicators for a high viral load. My doctor subscribed me with the antiviral Valacyclovir 2 months ago. I am getting better! Less fatigue, better sleep, less pain , normal movement and now I am working to regain my health. I am so grateful to have found a medication that is working. I hope that this may help somebody else!

The antiviral subset! This is what Ian Lipkin is so excited about: being able to accurately subset people biologically so that they get the right treatments. Continued good luck with it! There are some fascinating antiviral recovery stories from Dr. Lerner on Health Rising.

So happy to hear that (val)aciclovir works for you, Serena. It’s great that you have a doctor who suggested to try it out.

It’s been know for decades in the ME/CFS community that aciclovir works for some patients to suppress the inflammation.

I am also a member of this group. And I know two more patients who can also continue to work thanks to it.

I didn’t find a doctor who prescribed me the drug continually without the standard evidence that proves its effectivenes. That was horrible in the beginning but I then quickly decided to learn to pace perfectly. I have a very good although slow recovery in the meantime and am basically without relapses thanks to my good health management and pacing.

I was now able to get aciclovir to keep in reserve in case I have a flare-up. That’s a big relief for me. It allows me to travel and do other things that can be risky with ME because of many factors outside of your control and that has brought me back a feeling of being more free. Very nice!

There has even been done a study a couple of decades ago.

Unfortunately, they didn’t check whether people actually had a flare-up, in other words were in an acute phase of the illness. Therefore I think that these results are useless and it should be repeated.

I can recommend that you look up Jackie Cliffs research on ME/CFS pathomechanims in London at Brunel university. She researchers HHV-6b as the possible cause of ME/CFS. This would be a fit for our group of ME patients. Aciclovir is the standard anti-viral for herpes types simpley 1 & 2. However, according to the infectiology textbooks aciclovir has good activity against HHV-6b too.

Many years ago a rheumatologist suggested Plaquinol for me. My eye doctor (a retina specialist) asked me to be very, very careful. I decided not to try the Plaquinol. Not worth losing my vision for. I think it used to be often prescribed for Lupus; maybe still is.

sorry about typo: Plaquenil

Yes, methotrexate is widely used for autoimmune diseases such as lupus and rheumatoid arthritis. It might be a bit of a difficult treatment for people with ME/CFS because you must have frequent blood tests while taking it. I am trying it myself and am finding getting to the collection centre difficult. I have requested home visits and am hoping that will be approved.

Hydroxychroloquine (brand name Plaquenil) is a bit less onerous but you do have to have eye checks and it may be contraindicated if you have eye problems or a family history of eye problems. And then there’s the small but significant risks you were warned of.

It has been hard for me to decide to take DMARDs as I would hate to end up worse off, but in the end I decided to give it a try. A very difficult decision as with any medical intervention.

I avoid all the “big guns” drugs like the plague. I’ve never liked throwing drugs at illness to see if maybe it will help. Do No Harm is my motto.

Oh dear, I apologise that I gave that impression. I have several autoimmune diagnoses and other clues pointing in that direction, which is why I was put on DMARDs. And hydroxychloroquine and methotrexate, although needing regular monitoring, are not considered “big guns”. They are bottom-rung, low-risk options in the autoimmune treatment hierarchy. Still, definitely not something to try “throwing at an illness” without good reason, and that is not what happened in my case.

As you say, people should definitely be wary if any doctor wants to try something without being able to back that suggestion up with a good rationale.

Please excuse my clumsy reply – I just get enthusiastic about this topic because I think it has potential for some patients, with the right guidance and evidence, of course.

Sarah, thanks for your reply. My longtime neighbor across the hall from me dropped dead of a massive heart attack at age sixty. Methotrexate was one of the drugs he was given for his rheumatoid arthritis. I don’t trust any of them. We all have to make our choices, and pain is not fun. I imagine all of us with ME/CFS have a complex of autoimmune “stuff” (named as diseases yet or not) going on. Mine filled more than a page on testing. I just warn people because it can be easy to think of the short term and forget the longterm consequences when one is in a lot of pain.

Cameron

That’s interesting, Bridget. I have been wondering whether autonomic specialists would be trying out more-basic autoimmune treatments given they are easier to access.

I have a different type of OI syndrome and have other autoimmune diagnoses. I tried hydroxychloroquine, which didn’t help my OI, but surprisingly fixed some hand pain that nobody took notice of previously. Now I’m trying methotrexate and the early signs are promising.

I do hope the hydroxychloroquine works for you. I have watched Dr Grubb’s lectures over the years and the fact that he is also exploring the DMARD path is reassuring.

Like many others I have discovered that not only do I have fibromyalgia but I also suffer from PoTS, TMJ, hashimotos, and hypermobility syndrome. There seem to be many pieces to everyone’s puzzle. My pain issues began slowly in my 20’s then really amped up in mid to late thirties after giving birth to a second child. I was misdiagnosed numerous times and suffered horrific side-effects to the wrong meds. It wasn’t until I was 59 that I began down the right path. I’m 65 now and feel I have the full picture. Having this is helping make life somewhat manageable. I still have daily pain–the intensity is now mostly tolerable. I do have flares. If my neck is out then all bets are off and my whole body starts coming out of alignment. During summer the heat makes everything worse. I’ve developed heat intolerance. This is quite a challenge. I’m still working on finding the best ways to cope with this piece. My journey continues but I feel the worse time is behind me. Don’t give up. In some ways just knowing my full diagnosis has been a comfort. I do take cymbalta but it didn’t work for me until I discovered the hoshimotos. Once I was on thyroid meds I tried cymbalta again. Now it’s hugely helpful. I’ve also discovered the right dentist to work with my TMJ–huge difference after working with him since COVID-19. I see a fantastic myofascia person every 4 weeks. This helps and feels like a treat. I also see an atlas chiropractor. When my body complies she is a gift. I have accepted that my bendy body has a mind of its own and sometimes I just have to be patient and wait it out. I am recently experimenting with a few clothing items that help hold me in place. It helps but isn’t a full answer. I’ll take any help so basically I’ve cobbled together the things large and small that help.

Anita, your history sounds like mine, with the exception of having children. I developed severe endometriosis in my teens which resulted in a total hysterectomy at 28. I also have ME/CFS and developed Guillain-Barre after a nasty intestinal infection 12 years ago.

Hashi’s and GBS are my two autoimmune conditions, so it makes me wonder if FMS isn’t also an autoimmune condition. I don’t remember where I read this, but apparently folks who get one autoimmune disease are likely to get a total of at least three over their lifetimes. If FMS is autoimmune, I have my three.

You mentioned Hashi’s, so I’m wondering if you have the same problem I do with regard to converting T4 to T3. I can’t take Synthroid for this reason; I take desiccated plus liothyronine to keep my free T3 levels in the normal range. And even then, my Reverse T3 will slowly climb until it’s too high and subclinical hypothyroidism creeps in. I’m also vitamin D resistant, so supplementing becomes tricky because my calcitriol levels will shoot through the roof if I take more than 3000 IUs a week.

You mentioned heat intolerance, which is also worsening in me as time goes on (I’m in my late sixties). I used to do dry saunas and loved how much better my muscles felt, but can’t tolerate the heat anymore. I get upper torso and facial flushing so bad, I look like a cooked lobster for hours after getting out. One doctor believed it was rosacea, while another thought it was MCAS/mastocytosis. Interesting since I’ve been an allergy head my whole life.

I can’t help but feel like an important health component in folks like us continues to be overlooked. Why do so many of us also develop Hashi’s? FMS and Hashi’s seem to be joined at the hip. Makes sense to me that fibro would be autoimmune in nature.

As i continue to repeat, ME/CFS in its core is exercise intolerance, i.e. PEM. Therefore, those who consider ME/CFS to be caused or maintained by an autoimmune process need to spell out how exactly they explain PEM. I am surprised that this question does not seem to play a prominent role in this discussion (as a matter of fact it does not play a role at all 😉). But it should because if you don´t explain PEM you don´t explain ME/CFS.

We haven’t heard much about PEM in fibromyalgia but a paper was just published (which I cannot get at) which raises the subject

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40074568/

Recognizing the role of fibromyalgia in post-exertional malaise

Hi Cort, you probably mean this paper (the other one just refers to it):

https://academic.oup.com/painmedicine/article/23/6/1144/6404604

all the best!

Thanks! I completely missed that paper 🙂

“People with ME/CFS and FM experience small to moderate increases in pain severity after exercise, which confirms pain as a component of PEM and emphasizes its debilitating impact in ME/CFS and FM. ”

Not surprised to see PEM in FM! Given all the exercise studies in FM I kind of wondered about it but there are also quite a few studies showing problems with exercise.

Hi Herbert, I disagree. The core symptoms of ME/CFS are flu-like inflammatory symptoms, exhaustion, neurological problems and a weakened immune system. PEM just means that all these symptoms get worse efter exertion that exceeds the indivually limiting pathological exercise threshold.

PEM is rather the hallmark symptom because with it we can safely distinguish ME/CFS from other illnesses that have similar core symptoms.

It might not be discussed here how autoimmunity could explain the core symptoms and PEM. However, those who advance the autoimmunity hypothesis do say something about what they think it could work.

I am from the HHV-6b camp. Therefore I can’t give you their explanations but you can certainly look them up. Scheibenbogen in Berlin and the researchers around her on the one side and Akiko Iwasaki from Yale are the leaders in that field.

However, I recommend you read up on the HHV-6b hypothesis. It has the strongest case by far. Not only what’s been found in the research. The idea of a remitting relapsing chronified pattern of herpes reactivation can explain all the the core symptoms of ME uncluding PEM!

Flu-like means viral activation, exhaustion: viruses are known to be able to slow down mitochondrial metabolism in order to protect there replication from being disturbed. Neurological symptoms: HHV-6b is known to produce sub-acute (=smoldering) brain inflammation. The weakened immune system could be explained through the fact that HHV-6b attacks the immune systems T-cells.

PEM could be explained through the same idea: The immune system works best when stress and exertion are low because its fights need a ton of energy. And we also have to take into account that the T-cells are exhausted and even develop in a pathological pattern with the illness ongoing. Now, when a sick person goes over a certain activity level the damaged immune system hasn’t enough energy to control herpes 6b reactivation. After a short while – a couple of hours if you’re just out of an episode or up to three days if you have been in remission later – and the herpes infection and replication process is again in full bloom!

I was a participant in the video call organised by CureME whose lead researcher Jackie Cliff is tracking down the herpes 6b hypothesis. I asked her why it took so long to prove or rule out this theory.

She said that with the manpower and funds they have for now it will take them many more years to precisely say what role herpes 6b played in ME/CFS.

In my opinion it should be our main goal to get more money and researchers behind this hypothesis. Because it’s the best. It’s the farthest developed. It’s the most clear.

Hi Lina, I think you are right, I didn´t want to claim that ME/CFS was “only” PEM, but certainly wanted to say that you need to be able to explain this unique signature if you want to understand ME/CFS. Other than that I am also convinced that viral reactivation plays a central role in the pathobiological matrix and this may well be ignited through exercise-induced processes which in turn weaken the immune system. But then the question would be: why should exertion or stress of any kind, be it physical, cognitive, mental, orthostatic, sensory/audiovisual, chronobiological etc. be able to crash the immune system? In normal individuals the immune system remains rock stable after exercise, at least if its not excessive… so, evidently, here lies the central question: why is the stress response abnormal in ME/CFS? Here are my thoughts about it:

https://tinyurl.com/3b52we79

Thanks for you pitching in for the viral reactivation hypothesis!

Thanks for your reply, Herbert. I haven’t looked at your work yet. But thank you, it looks interesting and I’ll have a look at it.

As I said above, I don’t believe that the pathology processes in ME “crash” the immune system, as you describe it above. I think the problem might rather be that when a patient goes over their individual exertion threshold there is just not enough energy left for the immune system to control a virus reactivation.

As I mentioned and I am sure you’re aware of, over the last years the proof that something’s wrong with the T-cells in ME/CFS and that this gets worse the more sick people are has built up so far that we can safely say that T-cell pathology is a fact in ME.

By the way I just read a review on the T-cell pathology where the authors claim that this pathological picture is in fact already known – from cancer and chronic viral illnesses.

But back to my point: As long as patients stay under their ME acute phase triggering exertion threshold all is good. When we pace and rest well enough we’re or better our immune system even with the hampered T-cells is still able to keep a herpes 6b reactivation under control. But as soon as we violate it and spend too much energy elsewhere the immune system lacks that energy, is not 100% in control of the virus anymore and we get a flare-up.

That’s exactly what lovely herpes viruses are known for and why my GP likes to tell me about their “opportunistic” behaviour.

But there is even more to the HHV-6b hypothesis: It can not only explain PEM and why it takes about a three days run-up to a full blown episode, it can also say something about progression and deterioration.

Because HHV-6b is able to attack and damage T-cells, the immune system gets weaker and less capable to fight down herpes 6b reactivation with every ME episode. This could explain very well why the exertion threshold becomes lower and lower with the progression of the illness.

Personally, I think that this is extremly important knowledge for patients, because with this theory you can explain to them why it is crucial to try everything we can to prevent any one more flare-up.

We aren’t able to stabilise or even recover when you allow the virus again and again to mess with our immune system.

I saw that you see the neurons at the center of an explanation for all of this. I’m interested to have a look at your ideas – and disagree ; )

Hi Herbert, I had a glance at your paper. What can I say?

I congratulate you to the tons of work of reading and systematizing that you have done.

Your hypothesis is that each and every process in the body that plays a role in the regeneration of the organism after exertion breaks down in ME/CFS.

In my view, the argumentation then follows by overwhelming the reader with the results of studies that, you claim, prove that your hypothesis is true.

I am not sure, whether that is acually a sound way of presenting a hypothesis or an argument. There is this famous work of some German philosopher of science who made clear that we can only rule out hypotheses but not prove them.

On another level after reading half through the paper your hypothesis and the data that you claim support it doesn’t develop any depths and clarity.

Yet another impression for me was that some of the literature that you picked makes quite outlandish claims that are highly speculative, that not even the study that brings it up could corroborate in any way, and is certainly not replicated, but you treat it as and established fact:

My example is Avindra Nath’s claim that a region called the motor cortex is at the root of the problem of ME/CFS.

I am not sure whether you saw that neuroscientists who participated in the discussion here on Healthrising when Cort presented Nath’s study shared their knowledge that this was an area of the brain which was brought up often to pack into some completely speculative claims about how the functional brain scans could be interpreted. In other words: Here’s nothing behind.

(Ich kann dir das Buch Neuromythologie von Felix Hasler sehr empfehlen, um einen fundierten Einblick zu bekommen, wie die hirnbildgebenden Verfahren funktionieren und wie wenig belastbar deren Resultate sind und wie viel daran einfach ein immer noch anhaltender Hype.)

I think that you undermine your paper by bringing in too many of these completely unsubstantiated ideas about ME.

If you wanted to improve your work then I would recommend that you would reformulate your hypothesis by narrowing it to one concrete regeneration process in the body.

It could be a part of the muscles, or a part of the immune system, or the mitochondria, or the brain, and then make your hypothesis for that part of the body really clear (anschaulich) and simple and explain in detail why the literature specifically on that detail of the regeneration process supports your idea.

What is your idea about how such a pathological process could be triggered by so many different kinds of things like infections, trauma, chemotherapy ect.?

I know that this is probably useless but I’d still like to repeat that I’d recommend you to put this work away for some time and read up on everything that has been brought forward by the herpes in ME researchers over the past three decades and especially the past five years.

Again: Jackie Cliff has found HHV-6b in saliva in a large group of patients via PCR. The viral loads were linked to symptom severity. And the symptoms of ME/CFS and the over all course of the illness with it’s remitting and relapsing character do look like a problem with herpes reactivation. The T-cell pathology tells of a chronic viral infection. Prusty has found molecules that are a part of HHV-6b-synthesis in the brain. I could go on but I leave it here.

Look forward to hearing to what you are up next!

Hi Lina,

thank you for your input! You make a strong pitch for your own favorite hypothesis (which I find viable and which I am following, too). I think there is value in not being too uncompromising with regards to hypotheses. After all, ME/CFS is a complex disease with many open questions as to which processes are upstream and which are downstream. As Jackie Cliff´s team states with regards to the HHV reactivation hypothesis: “Herpesvirus reactivation might be a cause or consequence of dysregulated immune function seen in ME/CFS”. Same with an abnormal stress response, I agree! Let´s try to not get too stressed about differences in our understanding of a disease which is ugly enough?

Best,

Herbert

My pleasure Herbert. Thank you, that you offered your work to read.

I see it a bit differently from you: When there are competing hyoptheses then it is the course of good science to judge and rank or even dismiss them providing arguments for explaining why you do so.

I don’t understand why you criticise that as bad and driven by “distress”.

I see discussions, criticisms, and disagreements as productive and necessary for the advancement of science.

Your feedback on the contrary is an ad hominem argument. In philosophy we judge that as invalid and unconstructive to bring in into a discussion.

I’d be curious why you think that your hypothesis is superior to the HHV-6b theory. Judging from your last comment it seems that you lack any good arguments.

I am fully aware that Jackie Cliff hasn’t brought forward enough evidence to prove her hypothesis. When at the same time the evidence that we already have is so robust and convincing that it should be our main aim as ME/CFS patient that we advocate to prioritize the research into HHV-6b.

I think this is even more valid because Cliff’s hypothesis can be ruled out with the current technical possibilities. While your hypothesis or the idea of autoimmunity are yet so unclear and unspecific that we have no idea whether this research could bring direct important insights for the understanding of ME/CFS.

Hi Lina, I agree with you, but you have the wrong herpes virus. HHV-6 infects 90% of the population and is a common cause of childhood roseola. It can be tested for through Quest labs.

(From article in Very Well Health.) On the other hand, the initial infection with HHV-6A does not usually cause symptoms, and most people do not know they are infected. (Testing for HHV-6 A is only available through specialty labs like Coppe so we have no idea of its incidence in the population.)

Research shows HHV-6A often evades the immune system. As a result, it can move through the body undetected and invade different organs. This may not cause any apparent issues at first, but the virus can reactivate years later and trigger a wide range of illnesses.

However, research on the long-term effects of HHV-6A is still limited. At this point, virologists can’t say with certainty that HHV-6A directly causes many of these conditions. While considerable evidence links it to some illnesses, other ties are less certain. (Some researchers believe that HHV-6 A is not a subset of HHV-6 B, but an entirely different virus.)

Autoimmune Diseases

HHV-6A is believed to trigger several autoimmune diseases, including:

Guillain-Barre syndrome

Hashimoto’s thyroiditis9

Lupus

Sjögren’s disease

Cancer

Research suggests a link between HHV-6A and certain cancers. However, it is unclear whether the virus causes cancer or is just one of many contributing factors.

Cancers that may be connected to HHV-6A include:

Cervical cancer

Gastrointestinal cancers, such as colorectal cancer

Gliomas and other central nervous system tumors

Hodgkin lymphoma

Leukemia

Non-Hodgkin lymphomas

Neurological Conditions

Several neurological conditions may be linked to HHV-6A, including:

Alzheimer disease

Cognitive dysfunction, including delirium and amnesia

Encephalitis

Epilepsy

Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome

Multiple sclerosis

Optic neuritis

Seizure disorders

Other Conditions

HHV-6A can invade different organs and may be linked to various health problems. Other conditions related to HHV-6A reactivations include:

Colitis

Endocrine (hormonal) disorders

Heart disease, including myocarditis, arteriopathies, and left ventricle dysfunction

Kidney disease

Liver disease

Lung disease

Sarcoidosis

On the HHV-6 Foundation web site, artesunate is listed as an antiviral with excellent effectiveness against HHV-A and few side effects. Yet, other than Dr. Paul Cheney, I have never heard of any other doctor using artesunate.

One of the scientists, Dr. Ablashi who discovered HHV6-A also did a study on Nexavir, a new version of a very old anti-viral Kutapressin which also inhibited HHV6-A.

I didn’t pick it myself. It’s researchers like Bhupesh Prusty and Jackie Cliff who have found prove that 6b may play this central role in ME pathology.

Jackie Cliff and her team found it in saliva in patients via PCR. The viral loads corresponded to symptom severity.

Now they are assessing whether these acute infections arise opportunistically because of an ME flare-up or present the cause for ME and all its symptoms.

Because not only the ME outward symptoms look like herpes 6b but also the changes that have been found in the lab can be well explained through its reactivation, I see it as a no-brainer.

Hi Lina, This is the letter I wrote to Dr. Prusty in 2022

Dear Dr. Prusty,

In 1982, I picked up my son from school and he asked me “are you going to be in a bad mood again today”? This shook me a bit, but when I stopped to think about it, I hadn’t felt well in a while. I had become allergic to almost everything that hadn’t bothered me before. I also was having horrible headaches and chronic bacterial infections with reactions to medications used to treat them. As things went on, I was hit with a crushing fatigue. I was a three-mall a day shopper, but when I went out now, after 10 minutes or so, it was like a load of cement had been dumped on me.

I decided to tackle the allergy symptoms and spent a week having sublingual testing done out of town. I was reacting to everything, but also running short on funds so I was referred to an allergist/immunologist in our town.

After I told him my litany of complaints, he and his colleague, an immunologist at the University of Central Florida, ran some blood tests. After a few days, they called me back to have the tests repeated. I had a total of 372 T cells and a total reversal of T4/T8 and the same thing on the second round of testing. I think they thought I had HIV, but I was negative on repeated testing.

In 1984, these immunologists diagnosed me with chronic encephalopathy and immune deficiency. They put me on dextran sulfate (a non-anticoagulant heparinoid) and transfer factor. The dextran was obtained under orphan drug status from Germany. When I had one of the horrendous headaches, a shot of heparin would knock it out.

By 1986, my main doctor was reaching retirement age, so I began to see Dr. Paul Cheney, who was one of the first doctors to identify ME/CFS in Incline Village. He was very interested in HHV6-A, and I tested positive for this at a specialty lab he was using. Before his death, Dr. Cheney treated 12,000 patients from all over the world. He left no stone unturned in seeking the cause and most effective treatments for ME/CFS.

HHV-6 was discovered in the Gallo AIDS lab in 1986. At first, it was named HBLV because it was killing B cells, but later they discovered that it was also killing T cells. They renamed it HHV-6 and then, oddly, subdivided it into HHV-6 B, a cause of common childhood roseola and HHV-6 A, which we really have no good statistics on, because testing is not widely available.

My original immune tests closely mirrored non-HIV AIDS which the CDC was monitoring. Dr. Cheney also had other patients with reduced greatly T cells in his patient population.

Researchers at Tulane are studying Non-HIV AIDS or ICL as it has now been named. http://www.autoimmune.com/Non-HIVAIDSGen.html

I applaud your work on HHV-6. Based on my symptoms, I believe this to be the cause of an ongoing neuroinflammation. Perhaps you are aware of all of the information in this email. If not, I hope it will suggest further directions in your research.

Hi Betty!

“Based on my symptoms, I believe this to be the cause of an ongoing neuroinflammation.”

You said that above.

I think that I have the same. I am one of the patients who had a slow beginning and deterioration of the syndrome. At first, I think, it was only the immune system that was the place of inflammation. But then when I deteriorated to moderate I also began having low-intensity brain inflammation.

I didn’t find out about ME/CFS for a long time. So I was consulting neurologists and infectiologists in the hope that they would find out about which reactivated (herpes?) virus caused my symptoms.

But to no avail. ; )

About one year after finding out about ME/CFS. I was in a very bad shape at that time, I found out that herpes had been in discussion as a cause or an important part of ME/CFS for a long time. And I found the work of Maria Ariza, Bhupesh Prusty, Jackie Cliff and others.

I’m so happy that Jackie Cliff is now tracking that question down until they know what role HHV-6 plays in ME. : )

Finns det några pågående studier med dessa läkemedel för ME/CFS och Fibromyalgi i Sverige – eller planeras några att genomföras. Karolinska??

I always find it so interesting the doctors who seem to get so angry about the possibility of diseases and disorders fitting into or expanding disease/disorder categories. What does is really cost them to entertain the possibility of a new interpretation? Isn’t finding information to lead to better patient outcomes the important thing? More important than ego, anyway.

Good point. In complex disorders doctors should be open to new ideas and/or treatments, particularly since there has been so little progress, especially since some of these conditions have been recognized since the 1980s.

Dr. Clauw as of this year also believes that the “evidence strongly supports GET” as a treatment for ME/CFS. He seems to be a clinician that is unwilling to learn in the face of a mountain of evidence.

I have an abnormal ANA on lab testing every 3-4 months. I wonder if other ME/CFS or Long Covid patients have this also. Does this suggest autoimmunity?

Potentially – it might be worth considering whether you have any other signs of autoimmunity, family history, etc.

I have a normal ANA but have two (maybe three) autoimmune conditions, and have managed to talk my way into trying some low-level immunomodulatory treatments. The first one didn’t do what I hoped, but the second one is showing promise.

Annoyingly, as I’m sure you know, seemingly healthy people also sometimes have abnormal ANA results, although usually at a lower level.

I know I may be in the minority, but I have always maintained that these illnesses are an abnormal immune response to one or more viruses coupled with a unfortunate genetic predisposition

Hi, Dr. Pridgen,

It’s been a moment!!

Yes I agree viruses , immune mediated, perhaps predisposition or family history of autoimmunity, total dysregulation of multiple systems and sometimes multiple hits of infections

( per Amy Proal).

Ive been sick for decades…got sick while living in a motel room that had well water…for 35 yrs I got zero help…I got belittled.

After what felt like something growing inside me…my system unleashed a war, I suspect my immune system tried to unleash a war against the infection…and failed.

The fight went on and on until my system became exhausted.i ended up with what felt like my guts leaked into the rest of my body.

After much searching on my own, I decided on taking ivermectin and as of lately,fenbendazole.im happy to report my 2 inch lymph lumps that appeared when all hell broke loose, are now gone completely after 5 months of ivermectin and fenbendozole…my immune system has not began to function normally.

I know what a normal functional immune system feels like because when all hell broke loose in 93′ i decided to stop eating as I lost my appetite.much like whitney Dafoe it feels as if my immune system is stuck. I suspect when a leaky gut is present the nervous system is involved. I hope this helps someone. Again, my 2 inch lymph lumps are now gone from taking ivermectin and fenbendozole.

Dr.Pridgen and Cort- First thanks to Cort for giving enough data to help me decide what direction In I should go in to treat my FM. The data seemed to indicate there there is some immune system issues involved with FM. So I—and my brother who has same FM, reached out to Dr. Pridgen almost two years ago. I can say under his immune system protocol I am much better than when I started —and so is my brother. My brain fog, fatigue, pain, PEM,and sleep are all much better. At same time I continued and increased my indoor cycling and weight lifting, but I still have PEM—at reduced level.The PEM has not deterred me from the exercising because the benefits outweigh the costs—namely I always feel much better after I exercise even if it is not everlasting and at my age I need stronger muscles and more resilient bones. It would be interesting to see if adding something like IVIG and/or any other immune type drug to the mix would help shorten the time frame and have a stronger outcome. I do agree with Dr. Pridgen that there could be genetic component as my brother has had same issues. Thank you, Blaine

Congratulations 🙂

Hi Blaine, that is very encouraging to hear that you had a substantial benefit to Dr Pridgen’s Protocol

I have started on that journey for ME/CFS and Long Covid. I am a beginner and hope for great results once I am able to get all the meds . My Autonomic issues have caused some recent Medical Crises that have interfered with the protocol. But I am hopeful. I too would love IVIG or immune repair meds at some point.

You give me hope! Sandra

Glad you are experiencing a significant improvement in your quality of life.

I always joked for many years that I was born freaked out. Then I got my genes tested and found out it was true. I would also add that, for some people, a long-term activation of the flight/fight/ freeze/fawn (appease) response during childhood contributes to the likelihood of developing abnormal immune responses.

I see that my reply looks a little out of place in this thread. I was trying to reply to Dr. Pridgen’s originaal comments.

Just like we’ve clearly seen with Long COVID, I think it’s very likely there are auntie subgroups of FM where some people do have underlying autoimmune origins and some don’t. Probably if we could figure out how to reliably separate that, we could then observe clear differences in symptom type/ severity and hopefully tailor treatments. I think this is the main reason why so many FM trials fail– there’s such a broad diagnostic criteria with overlapping issues that we only ever see maybe 30% of patients have >30% effect.

I have been questioning whether I am dealing with Immune Mediated vs Autoimmune Issues or maybe both. A virus (EBV) caused a skin problem that

occurred at the same time as the systemic issues of ME/CFS over 30 yrs ago and a rare Autonomic Dysfunction (Baroreflex Failure).

I am about to start a monoclonal antibody drug for the skin. I am thinking maybe I can use my skin issue to qualify me for a monoclonal antibody that would better address both systemic and skin issues. You know two birds one stone. These drugs are $5 K a month so I get them free from Pharmaceutical Company.

If I use ME/CFS or Long Covid as dx I don’t qualify.

Some of us have multiple complex issues and we fall thru many of the cracks of the siloed specialties.

It seems that both Autoimmune and Immune Mediated Issues can be treated with some of the same drugs. I would love to try JAKs , GLPs, Rapamycin or Monoclonal Antibodies to move the needle on my conditions but……

Cort, PERPLEXITY knows you very well and quotes you often. 😃 I love Perplexity

more than the others and more than my Drs. Thanks!!!!

Ii tried all you listed.no benifits.GLP even made me worse

>One might choose FM to be an autoimmune disease.

Hell no! Autoimmune disease have no cure, it’s the worst thing that can happen to us.

I prefer the hypothesis that ME/CFS and Fibromyalgia are condition caused by a dysfunctional microbiome, that would mean that something can be done, in theory.

I wish the researchers would concentrate on cooperation and collaboration rather than each having his own pet theory. I suspect this has to do with getting funding for research. Each study starts over with a theory that is original instead of developing. Each study and scientist just “refutes” without fully explaining the results of other studies. It is obvious that academic and money reasons are driving these studies instead of any real desire to cure or relieve the disease – If they can find something that is unique they can make a drug to make money – It is nothing to do with helping those with the disease. Clauw is jpart of the the school that is pushing these horrible drugs that do nothing – and were first taken off the list and then through pressure from the drug companies put back on the list The financial motive behind all of these studies is the reason medical research is so slow and we keep hearing of all of these new and amazing concepts for 50 years (for me) and never any real progress.

My life completely changed once I started following the autoimmune diet developed for MS by Dr Wahls, (The Wahls protocol). I modified it to eliminate lectins, nightshades, and anything that triggered my symptoms while doing an elimination diet. My “healthy” diet full of legumes and whole grains had been crippling me.

Personally, this indicates there was an autoimmune component to my decades long crippling pain, fatigue, brain fog, etc..

I went from constant pain and being exhausted after a trip to the grocery store, to working ten hour days on my feet. I’m not “cured” – pacing and recovery time after exertion is crucial. But I can live an actual life now.