In Part II of Kyle McNease’s narrative of going from abundant health to a severe case of ME/CFS, and then back to relative health, Kyle experiences abandonment, takes a surrealistic a trip to a psychiatrist, and reflects on the scars his illness has left on his loved ones.

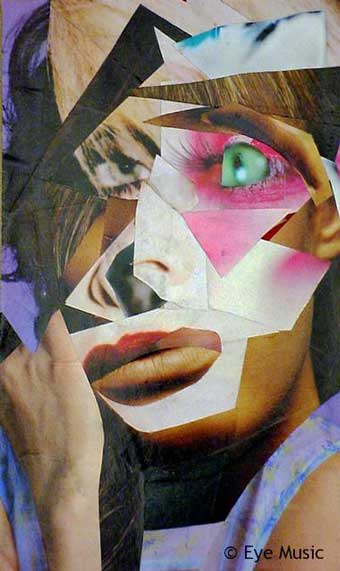

Thanks to Ken Anbender, a former ME/CFS patient, for allowing the use of his vivid artwork to further portray the hidden landscapes of ME/CFS. Check out Ken’s recovery story, “Twenty-Six Years of Hell: An ME/CFS/FM Recovery Story”, and see more of Ken’s art on his Eye Music website.

Kyle’s story is being presented in six parts on Health Rising.

Eros Lost

She was the love of my life. We were to be married in December. We met when we were just freshmen, but not like in that hackneyed song by the Verve Pipe. We dated all through undergrad. We were as close as two individuals could be. The lines between our borders were blurry; it was hard to tell where we started and stopped. We’d rehearsed being-together for so long that we were pros. We’d settled into “us” so deeply that we were like old chairs, bearing the outline and contours of the other person’s self.

As I laid there suspended in sickness, slowly dwindling into ghost, she would come in and stand by my bed. Snap, snap. On go the rubber gloves. She wasn’t allowed to touch me, for both of our sakes. It was the first time anything had come between us, and I’m not talking about the latex. I was on that uber-natural kick: couldn’t have paid me to put a drug in the well-oiled machine that was my body; didn’t even really need to. I hadn’t been to the doctor in years.

She’d never seen me (or anyone else for that matter) struggle. She said she loved me so much. I believed her. She said she couldn’t do this. “What do you mean, you can’t do this? Can’t do this? I can’t do this, but I don’t have any choice but to do this!” You see, for all of the loving and the closeness, it is inescapable that at the individual level of consciousness, you are alone. No one can take the pain for you. No one can suffer in your stead.

Then she knocked my tiny world off of its axis with 8 words: “Are you sure it’s not in your head?” “Get out! I can’t believe you would say that! Get out! Why would you say that?” I bleated in between puffs of the breathing machine.

I felt something break in me. I couldn’t hear it like I could with my arm and the needle, but I felt something cracking. “You know me. But, you know me. Don’t you know me? Don’t do this. Please don’t do this!”

She did that. Apparently, she did a lot of things while I was on my deathbed. Staying faithful wasn’t one of them. How could it be possible that while I was withering there on the brink of next breath and eternity that she could find solace in someone else’s arms? The idea, this reality was absurd. It marked the beginning of a period of absolute absurdity.

Absurdity!

Let me set the stage for you. I’m being evaluated by the esteemed psychiatrist Marshall Thurgood III. I remain slumped forward in my wheelchair with an I.V. attached to it.

Psychiatrist: Mr. McNuese, do you know why you’re here today?

Me: That’s not my name. Psychiatrist: What’s not your name? Me: McNuese

Psychiatrist: No, my name is Dr. Marshall Thurgood III. Your name is Keel McNuese. (speaks into his digital recorder: Patient is not properly oriented. Seems to think I’m him. Probe further into identity confusion.)

Me: Wait, what? That’s not what I meant. I don’t think you’re McNuese. McNuese doesn’t exist.

Psychiatrist: Em hmmm (he nods his head in affirmation). Tell me more. (he takes out his recorder: Patient maybe experiencing an existential crisis or a psychotic break. Explore further.) Me: You know I can hear you right?

Psychiatrist: (chuckles lightly but audibly). Standard procedure. Nothing to worry about. (he speaks into the recorder: Patient seems anxious, explore further.)

Me: Well, it isn’t true.

Psychiatrist: What isn’t true Mr. McNuese?

Me: STOP calling me that!

Psychiatrist: Calling you what? (speaks into recorder) Patient is definitely agitated. May need anxiolytic.

Me: McNuese

Psychiatrist: No, I’m Dr. Marshall Thurgood III. I am the psychiatrist here at Sacred Heart. You’re McNuese. (he speaks into recorder: Patient is definitely experiencing an existential identity crisis. Explore further.)

Me: NURSE! Nurse, please get me out of here! Nurse: Mr. McNuese, what seems to be the problem?

Psychiatrist: It’s okay. It’s just a mild decomposition. I’ve seen worse.

Me: (looks at nurse plaintively) You’ve got to get me out of here. This guy’s a joke; and for the record my name is Kyle McNease. Stop calling me McNuese. (nurse and psychiatrist both look at one another and shake their heads).

Psychiatrist: (brandishes his clipboard) It clearly says here that your name is Keel McNuese. Me: Well someone must have made a mistake. This is all just a mistake. I need to go back to my room now.

Psychiatrist: When we’re finished. But first, we need to talk about why you’re here.

Me: In the hospital? Psychiatrist: Yes

Me: The doctors say I have “the perfect storm of illness.” For some reason my immune system stopped working right and I’ve got pneumonia and all of these immune viruses attacking me.

Psychiatrist: (pulls out recorder: Patient has possible persecutory syndrome. Explore further.) Why do you insist on staying in that wheel chair?

Me: Maybe I missed something or don’t know enough about how this works, but you do know I’m in the hospital because I’m sick, right?

Psychiatrist: Of course you are. I’ve been brought in to help determine the etiology, whether it is strictly organic in nature or due to something else. There’s some speculation that you may be malingering.

Me: What does that mean?

Psychiatrist: If you don’t mind, let me ask the questions Mr. McNuese. It really will go better that way. Now, am I to understand that you withdrew from university?

Me: Well, um, I’m not really sure about all of that, you know, like the way it went down. I got really sick and had to be picked up from school and taken to the hospital. I’ve just been in and out of the hospital, but I think my parents talked with my university and I’ve been withdrawn.

Psychiatrist: Who picked you up from university?

Me: My mom.

Psychiatrist: (writes something down on the clipboard). Em, I see. And who took care of your withdrawal?

Me: My parents.

Psychiatrist: Who cooks your meals?

Me: My parents.

Psychiatrist: Em, interesting. Who pays your bills?

Me: Um, since I’m in the hospital my parents are taking care of them.

Psychiatrist: (speaks into the recorder: Patient seems very defensive. Explore further.) What about hanging out with your friends? When’s the last time you did something to get you out of the house?

Me: I just feel like we’re not on the same page or something. This is my life. This is what I do now. My life is the hospital and doctors’ appointments. So, I don’t see anyone anymore.

Psychiatrist: (speaks into recorder: Definitely axis two activity. Schizotypal personality traits. Refuses to have anything to do with his friends. Can’t maintain meaningful relationships, except with parents. Explore further.) Would you say that you are depressed, Mr. McNuese?

Me: I don’t think so.

Psychiatrist: (loudly speaks into recorder: DENIES depression.) So, you’re happy with your life?

Me: Of course not. Who would be happy like this? It’s just that I didn’t get here because of depression, you know? I mean, yes, it is depressing to be sick and to have lost everything that matters to me, but if I weren’t sick, then I would be back to myself, back to being happy. I want to be myself again. I want to feel like living again.

Psychiatrist: Feel like living? Do you want to die? Are you having suicidal thoughts Mr. McNuese?

Me: That’s not the way I mean that. It’s just that I am so sick so much of the time and am racked by pain that keeps me awake. I have this ravenous insomnia because of the pain. Nothing can seem to make the pain stop hurting, especially in my legs. Sometimes in desperation, I feel like if I could just have them cut off I’d feel some relief. I don’t want to die though, so no. No, I’m scared of dying. I just want things to go back to the way they were.

Psychiatrist: (speaks into recorder: Has issues with his legs. Possible body dysmorphic disorder. Explore further.) Mr. McNuese, I’m getting paged, which means that we’re going to have to wrap up this evaluation. Based on what I’ve seen and heard today, you need to begin treatment for clinical depression right away.

Me: I told you my name is Kyle McNease and I’m not depressed. I’m sick.

Psychiatrist: Look, Mr. McNuese, I’ve been doing this for 6 weeks now, so you’re not going to pull the wool over my eyes. I know clinical depression when I see it. You’ve got all the classical signs and symptoms. You are sick, but it’s in your head. But, don’t worry; I’m writing you a script for a cocktail of drugs that should help.

Me: In my head? Haven’t you been listening? I’m not depressed. Nothing changed about me or my outlook on life before this illness started. So, even if I were depressed, it wouldn’t be the reason I’m sick. Something’s wrong with my immune system.

Psychiatrist: (speaks into recorder: Patient has expansive ego. Thinks he’s a diagnostician.) Why don’t you calm down and leave the doctoring to those of us trained to do so. I’d love to continue talking a while longer, but I really must go. I will be sure to get the nurse to bring you your meds stat. Thank you Mr. McNuese. That will be all. (calls for nurse). Nurse, go ahead and take him back to his room, as he calls it. When his meds are ready, take them to him and make sure he swallows. He’s extremely defiant.

And the nurse, unlike my ex-fiancée, was loyal and faithful to his charge. Those drugs were forced upon me and into me. They weren’t treating a patient or an illness. They were after docility. They won, and meanwhile I became catatonic.

Over 1,278 long days and longer nights I lay shipwrecked, marooned on an island for misfit diagnoses. 3.5 years of suffering, wracked by an invisible yet insidious enemy. My head was placed between pillows to keep it from shaking uncontrollably. I was too weak to even lie down and hold my head still. My energy was dissipated by something cellular, something they couldn’t find.

Worse than not being able to walk or talk or read was the fact that I couldn’t go to the bathroom on my own. This one memory stands out in my mind so clearly. The doctors wanted another series of tests, so I had to be run through a CAT (computerized axil tomography) scan. In order for them to get the kind of images they needed, I was pumped full of more radioactive dye. By this time, wasn’t I already glowing?

Then, I was rolled out of my room into the testing area. I was rolled out of my hospital bed and onto the hard table that slides into the CAT scanner. “Take deep breaths but don’t move, or we’ll have to start it all over,” a disembodied voice rings out over the intercom. One problem: I had to urinate like a rushing race- horse. All of those fluids being jostled around by the scanner proved too much for my bladder.

“I really need to go to the bathroom,” I say back to the disembodied voice. “Just a few minutes more!” “Look, I don’t have a few minutes more. If we don’t stop this test, I’m going to wiz everywhere. I can’t help it. I gotta go.”

A nurse reluctantly came in the room and says, “Okay, go.” “I um, I can’t get up. I um, I can’t walk.” “Oh, well, I will help you then.” The nurse assists me in getting off of that ice-cold machine and over to a little potty with a built-in plastic container designed to collect and show how much fluid you evacuate. I knew it wasn’t going to be enough. Sometimes you just know when it’s going to be a monsoon.

As I darted my eyes back and forth, I could tell this was going to devolve into a Mel Brooks moment. “Um, this thing is um, it’s filling up and I’ve still got to go.” “Can you hold the rest of it until you get back to your room?” “No. I’m so sorry… but I mean this is bad. Can’t stop it.”

So, the nurse comes and hugs me up to a standing position, does some kind of swim move to reposition herself. She’s holding me around the waist and walking me forward in what looked like an awkward dance. She didn’t know what else to do, so she just started grabbing at the nearest containers. She finally secured a vomit catchment and with one arm wrapped around my chest, she put the receptacle down to capture the streaming urine.

My head was uncomfortably resting on her as she had to balance this shaking, streaming shell of a man. I know she was a trained professional, but holding some random guy’s penis is probably not how she wanted to spend her day. Being that helpless and exposed was surely not how I envisioned my life. I learned that there are definitely two kinds of adult nudity in this life: one a virile, sexy-kind that arouses passion in the heart of the beholder; the other, an exposition of indignity that couldn’t arouse passion in the heart of a beer-holder.

Love Song

My groundhog day of suffering was to lay there, shaking, sweating, and gripped with pain—while I watched my mom feed me, spoonful by spoonful. Reminds me of Prufrock’s words:

For I have known them all already, known them all:

Have known the evenings, mornings, afternoons,

I have measured out my life with coffee spoons;

I know the voices dying with a dying fall

Beneath the music from a farther room. (Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock. Eliot, 1998, p. 2-3).

It was as if I was looking in on this cruel and backwards scene that had become my life. To see that kind of pain on my loved ones’ faces and know that I was somehow the cause of it; and that there was nothing I could do to help… was and is brutal.

I’m a firm believer in this theory I made up and tested. It runs something like this: When you’re toying with the idea of your own mortality, trying to reason through your own impending demise, it remains an intellectual endeavor. You know you’re sick and dying, but it is not until you see that confirmed on the face of someone else that you feel it to be true, undeniable.

You can always tell how sick you are by looking at the face of someone who loves you. If there are tears, it’s bad. If they have to steel themselves before speaking to you, it’s worse.

Let me take back that comment about not being able to help; I could help by subjecting myself to every test or treatment that stood even a remote chance of improving my condition. So, my father would gently carry me in his arms, like the wounded animal I was, and lay me in the back of the van—which had become my hospital chariot.

I certainly developed a new respect for all of the wagon-travelers of the past. If I was jostled that much in a comfortable automobile with suspension, I can’t imagine what their elderly, pregnant and sick went through and the will they had to possess to make it. Now, we call that ethos rugged, but they called it necessity. And, I have this deep, nagging suspicion that if one of those pioneers had my life, she’d make more of it than I have.

Even in my suffering moments, I got to do it in a controlled environment; I always had a roof over my head. Even though I was sick, I still had central heating and air. Even though I couldn’t get up and run around, I could stay still in a hospital bed. It makes me look back over history with a new appreciation for our ancestors. Everything they did, they did in what would be considered impossible situations by us today. If one of them got an infected tooth, they died in excruciating pain. For many, something as simple as a fever or cough spelled the end. An insect or snake bite and you were done.

As for me, I was taken to see the best immunologists, infectious disease specialists, endocrinologists, and cardiologists around. Sometimes it was just my blood that made the trip for me.

Kyle McNease – The Suffering of One is the Suffering of All – An ME/CFS Narrative

- Pt I: REELing

- Pt. II: Eros Lost, Absurdity and A Love Song

- Pt III: “Didn’t Life Know I Had Plans?”

- Pt IV: “Didn’t Life Know We Had So Many Plans?”

- Pt. V: Remorseful Survivor – Kyle Finds An Answer

Ken Anbender’s Art

Thanks so much sharing your story in such a beautifully written fashion. Your bare truth, the awful truth, in a readable manner sometimes funny, sometimes sad, but always moving. I am riveted and can’t wait for the next part! The artwork is also stunning!

Oh, Kyle…You have such a gift with the written word! Thank you for taking your life’s worst tragedy, and placing it on the page–for us to see the horror your life had become. I too was stricken… 33+ years ago, I could feel how your life shattered like broken glass!

Keep Writing!!!

This rings so true, so scarily true. The words our doctors spoke may not of been the same but the sentiments were exactly the same. 2013 Australia.

Thank you. You give a rare gift through your writing, so vivid, so somehow vital. I have had what I would call a moderate case of FM/ME. The ME was only diagnosed 2 years ago while this illness has been slowly claiming more of me over 40 years. A psychiatrist told me I couldn’t have FM because that only very driven professional women got that. So she diagnosed me with Major depression. And I was relieved!

I was a psychotherapist so I figured I could work with that. I just kept getting sicker and thinking it was all in my head. This was back before the internet so there was nothing to do and nowhere to go. Even my husband thought I was malingering.

I’ve never posted before but your writing about your experience touched me so deeply I had to respond even though my experience is so different from mine. It takes immense courage and some sort of ineffable stamina to live through what you have experienced. Thank you from the bottom of my heart!

Ineffable stamina indeed! That’s a great way to describe whatever gets us through these situations. Some we don’t even know we have…

I just feel so sad and so outraged!

Hi Kyle,

This needs to be published for the general public. It touches my soul so deeply. It is a wonderful piece of writing. The world needs a book like this.

Agreed!

Beautifully raw , the spicy truth , deeply resonating. Thanks so much for expressing what some of us cannot. Please keep writing.

Thank you Kyle for writing about the darkest part of your life. I love your writing style. I was moved to both laugh and cry at the total absurdity of the treatment by the psychiatrist and the diagnosis of depression.

I can closely relate, pleading with doctors to understand that I wasn’t depressed. I was motivated, I was a sporty girl who just wanted to get back to being me. I wasn’t depressed when the symptoms started so how could it be depression?

Thanks Cort for bringing this to us and yes the world needs to read this too.

“I wasn’t depressed when the symptoms started so how could it be depression?”

That about sums it up…..I wonder how much of this common misdiagnosis is just pure laziness on doctors part; their not being careful, not thinking clearly – their skating by on their preconceived ideas…

I imagine a computer program could do much better

isnt that why so many have turned to internet research?

thank you for making information so much more readily available and concise and caring

Crazy good!!

Quite frankly, feeling unwell to my core reading about the life, and possible life, you, and all of the rest of us, have had to let go. And at the difficulty of navigating/negotiating one’s way through the medical system and with medical professionals, without doing further damage.

Thank for such beautiful writing which resonates with the experiences of so many of us with this illness. Last week I posted a blog about my own absurd encounter with a psychiatrist, four years into my illness: https://dancinginthedark.home.blog/2019/06/18/sex-whales-and-a-french-psychiatrist/

Amazing – truly amazing how we can turn our belief systems into pretzels and wrap them around just about anything!

From your blog:

“‘Masturbation’ he says.

‘This will be your problem. It is not possible for a woman of 21 to live without sex. Therefore you must be masturbating, and because of your faith you are feeling guilty about this, and this guilt is making you ill.’”

Reading Kyle’s account is heart rendering, but he is so much braver than I am! It only took the opinion of one neurologist to make me crawl back into my shell and not wish to seek further appointments with anyone medically trained, other than my GP (UK) who will treat whatever symptoms I ask for, which are only those I find unbearable. Others I am learning to live with after 4 years, but life is so restricted for me and others affected. Looking forward to reading more of this very engaging account.

That’s very brave of you to acknowledge that Lin and thanks for doing so publicly so that the many, many other people who have acted in exactly the same way know they are not alone 🙂

Thank you, Kyle, for telling the truth in such a compelling way about this disease and how patients are treated. Although I live most of my life in bed, your account managed to make me count my blessings. My husband hasn’t left me, and I’m not in the hospital, subject to the abuse of arrogant and ignorant doctors. I’m sorry you were treated so awfully when you were most down.

Thank you Kyle. I wonder if you could write about how you experinced care and how it could be improved? I wonder too, if since it is now behind you, if your parents share your gift for writting and if they would be prepared to discuss how best to care for the seriously affected sufferer? The isolating and heart wrenching is difficult for a parent to keep off their face. How do they prevent the anguish they feel from confirming hopelssness to their loved one? How could they better promote independance and agency and not infantalise a person who has been rendered helpless?

How should the carer respond to this total depeandance? How could they do better.

How have YOU recovered from being a dependant again? have you re-established an adult relationship with your parents?

The issues of physcial care are difficult but solvable with suffiecent support (although they take a toll on the body as well as the psyche of the carer), but the issues of the relationships of care for an adult loved one do not get much of an airing, yet seem to me to go to the most painful heart of the truth of severe ME.

I can’t say my FM was really helped by any of the numerous medicos I’ve seen in the last 30 years but I thank the stars for not having to endure any degradation or humiliation like the writer. Medicine at it’s worst.

Oh Kyle, how terrible. I studied Ken Kesey’s novel “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” when I was a high school student. It took on a new significance after I got ME/CFS. It is a strange and surreal experience to be completely sane and be treated like you are not and, conversely, to be very sick and told that you are not. I’m really sorry for the extreme suffering you experienced. Thank you so much for sharing your beautiful writing with us.

The dialogue with the nincompoop psychiatrist really sums up the uselessness of those specialists when faced with facts their eyes cannot see. And then they filled you with useless drugs. Thanks for the concise description. I cannot convey my experiences, less extreme than yours, without getting angry, which takes away clarity. You are clear.

It is so distressing that caregivers do not listen and do not even know your name and make wild judgements from one sentence.The invisibility that you become because no one is listening is horrific. The denial that you are truly ill is another issue, it becomes the attitude of the general population who feel obligated to tell you that you are not ill-you have something wrong with you.

Thanks Kyle for writing about such tragic and surreal period in your life with equally surreal but oh so recognizable words. It is truly a masterpiece!

Gracias por describir de una manera tan bonita todo lo que has vivido. Me has conmovido, me siento reflejada. Mi lucha es diaria porque se reconozca mi enfermedad, porque los médicos me respeten y por seguir siendo la mujer que siempre he sido.Gracias.

Google translate – “Thank you for describing in such a beautiful way everything you have lived. You have touched me, I feel reflected. My fight is daily because my illness is recognized, because doctors respect me and for being the woman I have always been. Thank you.”