The Ron Tompkins Effect

Ron Tompkins had recently come back from a meeting with over a dozen MD’s and specialists from Mass General Hospital who’d evinced a strong interest in ME/CFS. Dr. Bateman has said it’s easy to get researchers, at least, interested in this disease but doctors – they tend to be the really tough sells. Yet, here was Tompkins, not long after creating the Harvard ME/CFS Collaboration with Wenzhong Xiao, PhD, meeting with 14 of them.

I wondered how that could have happened and then realized what was going on. It was the “Ron Davis effect” – showing up at Harvard. The effect occurs when a highly respected researcher takes ME/CFS on in a big way, causing the people around him to sign on. Ron Tompkins himself and the Center he leads is a result of the “Ron Davis effect”.

Tompkins has been at Mass General for 40 years, during which time he’s managed large research efforts garnering $200 million (gulp) in NIH grants.

Now the “Ron Tompkins effect” at Harvard – which has been funded by the Open Medicine Foundation – has produced a large team of international researchers and over dozen MD’s willing to collaborate on working on ME/CFS.

There’s more to it than that, though. Location does matter. Tompkins described Harvard and Mass General as hotbeds of medical and intellectual curiosity. The doctors there are used to dealing with complex cases of chronic illness. They tend to be heavily involved in research. They tend to thrive on challenges. They probably don’t succumb to dogma so easily.

In fact, Tompkins reported that they call their ME/CFS patients their “five o’clock patients” because they tend to save them for the end of the day when they can spend more time with them. Sometimes, he reported, the doctor will be there long after the staff has gone home.

Still, the idea that Tompkins was meeting with specialists – neurologists, rheumatologists, infectious disease specialists, and even a mitochondrial genetic specialist – was a shock to me. I thought Tompkins was leading an ME/CFS research center, but he is clearly thinking bigger than that.

It turns out that Tompkins and Xiao want to transform how people with ME/CFS within the Harvard hospital system are treated as well. They want patients to get the right tests and get seen by the right specialists. They want the doctors they’re working with to be on the same page with regard to diagnostic protocols, standard testing protocols, referrals, etc. Ultimately, a kind of template could be created that groups at other institutions could use. The doctors’ group plans to meet quarterly.

Thinking Big – A Harvard Center of Excellence

It is the intent for the many clinicians and investigators at the Harvard-affiliated Hospitals to establish an institution-wide Center of Excellence for Chronic, Complex Diseases, THe Harvard ME/CFS Collaboration

As to the Center of Excellence? An academic medical center integrating medical and research efforts on the Harvard campus? That’s a major, long term goal but it’s one Tompkins is quite serious about.

The Center would not be just about ME/CFS – and that’s the good news. ME/CFS is clearly associated with diseases like fibromyalgia but has been sitting in its own little silo with its own researchers, conferences, and even doctors for decades – losing opportunity after opportunity for funding and understanding. It’s impossible that the quintessential pain and fatigue disorder (FM) couldn’t benefit from being studied with the quintessential fatigue and pain disorder (ME/CFS) but they rarely are. Since both suffer from similar funding issues, creating a center that focuses on them (and others) can only help everyone. That is what Tompkins aims to do.

By fostering collaboration between specialists who have long studied ME/CFS, post-treatment Lyme Disease, and Fibromyalgia in isolation, we aim to break down barriers and share learnings, leading to new advances in the understanding and treatment of these related diseases. Harvard Collaboration

The Center would draw on a wide variety of disciplines (internal medicine, primary care, infectious disease, neurology, surgery, neurosurgery, genetics, pediatrics, rheumatology, cardiology, pulmonology, psychiatry, psychology, and possibly others).

The really interesting thing about the potential Center is that the interest is already there. In fact, the interest in a potential Center has been so strong that Tompkins was convinced if he had the money, he could quickly open a fully staffed Center of Excellence on the Harvard campus. That’s pretty shocking. From the Collaborative Center website:

“The COE… would be extraordinarily well-supported by a very large group of extremely knowledgeable and committed clinicians and investigators at the Harvard-affiliated Hospitals as well as a key cohort of longstanding critical collaborators.”

“Complete implementation of a fully functional COE would be straightforward as there are dozens of clinicians and investigators who have been working independently for decades who would welcome the opportunity to work together as a very cohesive clinical and investigational internationally-recognized Center of Excellence.”

I don’t know about you but the sound of an internationally recognized Center of Excellence sends a shiver up my spine. Creating a Center like this would take a major philanthropic effort but because the Center would include ME/CFS, fibromyalgia, post-treatment Lyme disease and, I imagine, other neglected diseases (postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome, mast cell activation syndrome, irritable bowel syndrome, Gulf War Illness, environmental illness, mitochondrial disorders), it’s got quite a large audience – and a very hungry audience – to draw from.

Put all those illnesses together and you have a patient population in the U.S. that runs to the tens of millions. None of these diseases or the people who have them are getting their due. Tens of millions of people are receiving substandard medical treatment and a mostly blind eye from the NIH. That’s tens of millions of people who would undoubtedly love to finally have a Center, at one of the top medical schools in the world, devoted to their illness.

That’s a pretty nice crowd to draw from. Anyone want to get their name on a building?

The Harvard Collaboration Takes on the Muscles and Exercise

Two studies are underway and many more are planned.

The Muscle Study

We all know about the exercise (activity) intolerance in ME/CFS – the disease is practically defined by it, but where is it coming from? Is it the immune system? The brain? The autonomic nervous system? The muscles? (All of them?)

It’s about time someone took a deep, deep, deep dive into the muscles in ME/CFS and that’s what the Harvard Collaboration is doing. Tompkins described an international effort stretching from the U.K. to Sweden to the U.S.

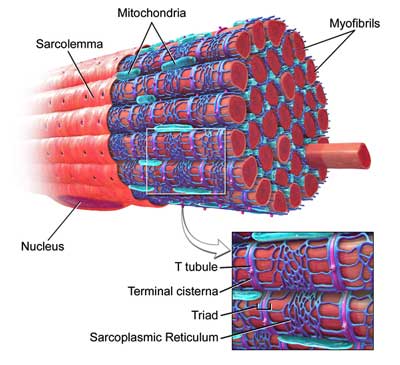

Their working hypothesis has a familiar theme – with a twist. They believe, like others, that exercise-induced inflammation (e.g. cytokines) is at the heart of the post-exertional malaise (PEM), but they’ve identified a different target. They believe exercise may doing lasting damage to the small myofibrills which make up our muscle fibers.

It’s true that exercise – or rather, “muscular stress” – damages myofibrills in healthy people (hence the aching muscles a day or two later) but the damage is usually quickly resolved. Tompkins believes the muscle repair processes to clean up that damage may be broken in ME/CFS – hence the often day or two delay before peak PEM symptoms hit. Given the central role the mitochondria play in the muscle repair process, he believes they may be involved as well.

The Gist

The ME/CFS Studies

One study will extensively examine the molecular components of the blood to try and understand why the hearts of one subset of ME/CFS patients are not receiving normal amounts of blood (preload failure).

That same study will try to understand why the blood returning to the heart of another subset has higher than normal oxygen content. The higher than normal oxygen content indicates that the oxygen the muscles need to extract from the blood in order to exercise is not getting extracted.

Another international study will do intensive analyses of muscle biopsies from ME/CFS patients at rest in an attempt to begin to understand why exercise is so difficult.

The working hypothesis is that inflammation produced during exercise is damaging the muscle fibers and impacting the muscle repair process.

What they won’t be able to do in the first study – but would really like to – is include an exercise stressor. It turns out that Mass General, the first site in the U.S. to employ an Institutional Review Board (IRB), takes its mission seriously. It takes it articularly seriously when muscle biopsies are concerned, making an already demanding review process even more “complicated and prolonged”. Mass General won’t allow them to do an exercise study first, so the first study will examine the muscles at rest, which will pave the way for a before and after exercise study.

Cashing In: The ICPET Omics Study

Next, the group will “cash in” on a fantastic resource – David Systrom’s blood samples gathered from people with ME/CFS doing invasive cardiopulmonary exercise tests (ICEPT’s). Systrom, a pulmonologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital on the Harvard campus, has gathered a massive collection of oxygen-rich arterial and oxygen-depleted venous blood samples.

(Oxygen-rich blood flows through the arteries to the muscles where the oxygen gets used up and the depleted blood is moved to the veins which return it to right-hand side of the heart. The right-hand side of the heart then moves it to the lungs, where it gets oxygenated, and flows to the left-hand side of the heart, where it gets pumped back into the arteries…)

Systrom’s found two forms of “preload failure” in ME/CFS – a low-flow and a high-flow group.

Low Flow (Normal Oxygen)

In the low-flow group, sympathetic nervous system problems may be causing some venous blood to get shunted to the arteries, thus reducing the amount of blood that returns to the heart (preload failure).

Importantly, the oxygen content of this group’s venous blood is normal – meaning that the muscles are taking up normal amounts of oxygen from the arterial blood. The muscles, however, appear to be getting low levels of blood, thus putting them at risk for hypoxia, lactate and CO accumulations.

High-Flow (Low Oxygen)

The high-flow group has a entirely different problem. Their blood flows are normal, but the oxygen content of their venous blood is not.

In their case sufficient amounts of blood appear to be getting to the muscles, but the muscle cells are not pulling normal amounts of oxygen from it. Either the capillary blood is getting pulled away into the microcirculation before it reaches the muscles, or the muscle cells themselves are having trouble utilizing the oxygen in the blood.

The Harvard Collaboration is going to examine the cytokines, proteomics and metabolomics in both groups. Their study is in the IRB approval process now. Tompkins is confident the study will uncover important new findings about ME/CFS.

These new technologies are illuminating, but what they aren’t is cheap. An in-depth examination of Systrom’s samples will cost between $1,000-$1,500 per sample. The three time points (before, during and after exercise) means 90 samples need to be analyzed for a 30-person study.

Tompkins is well aware of the NIH’s intransigence regarding ME/CFS. All this work, he said, should be funded on the NIH’s dime but it’s not. Everything that’s happening at the Harvard Collaboration is being funded by patients contributing to the Open Medicine Foundation. Tompkins and Xiao will use the data they gather for grant applications, but for now it’s the patients and their supporters that are keeping this work alive.

Conclusion

The interest Tompkins has received from both doctors and researchers is gratifying, and is probably in no small part to what one could call the “the Ron Davis effect” – an effect which occurs when a major researcher takes on ME/CFS. Things basically just start to move.

The same has clearly happened with Tompkins who seems to been able to elicit a significantly greater degree of interest in ME/CFS from medical specialists at Harvard than elsewhere. Those specialists are meeting regularly with Tompkins to streamline and improve their approach to ME/CFS.

Tompkins major (major) goal is building a Center of Excellence for ME/CFS and related diseases on the Harvard campus. It’s a huge undertaking but in some ways the hardest part is done: the interest is there and Tompkins believes he could quickly staff one right now.

Lastly, the Harvard ME/CFS collaboration has two studies underway. One, an international collaboration involving the U.S., the U.K. and Sweden, will probe more deeply into the muscles of people with ME/CFS than has ever been before.

The other will extensively analyse David Systrom’s blood samples in an attempt to understand what’s happening with the two subsets Systrom’s invasive exercise tests have uncovered in ME/CFS. One is characterized by low blood flows with normal oxygen levels, while the other is characterized by normal blood flows which reach the heart with higher than normal oxygen levels – indicating that the muscles have not received the fuel (oxygen) they should have.

Health Rising’s Quickie Summer Donation Drive is On!

Health Rising’s Quickie Summer Donation Drive is On!

This is very exciting news! I can’t wait to hear more about it!

just love all of you!!

This is fascinating! I’ve been on supplemental oxygen for years because the oxygen uptake in my tissues is so poor. None of my doctors have been able to explain exactly why. Can’t wait to see what this study finds out.

Mast Cell – Histamine (Immunotherapy With Histamine) | Health Rising’s Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) and Fibromyalgia Forums

https://www.healthrising.org/forums/threads/mast-cell-histamine-immunotherapy-with-histamine.6233/

This may be of interest. Can address some of these issues.

The Intriguing Role of Histamine in Exercise Responses.

https://journals.lww.com/acsm-essr/fulltext/2017/01000/The_Intriguing_Role_of_Histamine_in_Exercise.7.aspx

Induction of the Histamine-Forming Enzyme Histidine Decarboxylase in Skeletal Muscles by Prolonged Muscular Work: Histological Demonstration and Mediation by Cytokines.

https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/bpb/40/8/40_b17-00112/_article

Roles of Histamine in Exercise-Induced Fatigue: Favouring Endurance and Protecting against Exhaustion.

https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/bpb/35/1/35_1_91/_article

Understanding neuromuscular disorders in chronic fatigue syndrome.

https://f1000research.com/articles/8-2020

Thank you for this list. It’s certainly interesting to me that muscle activity directly produces histamine; without anti-histamines, just getting off the couch is enough to trigger widespread itching.

Since mast cells have histamine receptors, the muscle-produced histamine could stimulate the mast cells to produce even more histamine, along with other mast cell mediators (there are about 200).

Some day immunologists will ditch the idea that mast cells are “the appendix of the immune system” [1] and really look to see if mast cells have a role in ME. Perhaps this new Harvard collaboration will lead to that happy day.

[1] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2193441/

Thanks for that link, Issie. Must be brain fog that I could be so oblivious to the forum’s existence! Am waiting for ‘confirmation.’

Normally I used to hang out on Inspire as Ninigirl in the EDS community. Now, not so much as my fatigue has become the dominate symptom (besides my other major issues; achalasia, POTS and DCIS).

I most definitely have PEM and often feel generally miserable, but not so much MCAS nor major food intolerances–but am VERY sensitive to many medications. Brain is still firing along, albeit the word finding ability is starting to go ‘south.’

I look forward to pursuing the ‘stacks’ in the forum to see if I can glean any useful ideas! Thanks again!

There was just an effort to get Bill Gates to watch Unrest (on Likewise, he asked for movie and tv recommendations). For those who don’t know, the ME/CFS community made Unrest the top recommendation. If we could get Mr. Gates interested in supporting ME/CFS, maybe he could put his name on that Harvard center and/or help (with friends/colleagues/etc) in other ways!

Thank you for this update; this would be incredible!

I watched a documentary on him. He is brilliant. What a mind he has.

Bill Gates.

Yes, and he’s a wonderful person and philanthropist too.

I wonder what organization would be the best to try to entice him into the ME/CFS world?

Be careful with the ‘wonderful person’ moniker, we don’t know him in person. However, it would be amazing if he would somehow attach his name (and some dollars) to ME/CFS research. It would result in clamoring from millions that he do the same with reasearch for many, many other overlooked/under-researched conditions. Jenn Brea’s film would surely make some kind of impression, if he watched it.

That’s a great idea…. I live with hope of one day living the life I once new …thank u

We don’t know Bill Gates in person? We don’t know anyone in person we just want help desperately!!!

I find it interesting that we have so many ME/CFS news stories on all the research going on and the results of them. I also find it interesting when we applaud a non-medical person having watched an ME documentary.

I find all this interesting because after having severe ME and Fibro for 20+ years and not finding one physicians who had even heard of this disease! So at the age of 58, we pick up and retire to another State and a very large City.

After seeing 22 physicians in 28 months… not one has ever heard of ME/CFS! One Doctor did say “Honey; we all have chronic fatigue from time to time” This is AFTER we told him that I am completely bed bound. I can only get help getting a bed bath and hair washed once every 2 months or so. I do manage to brush my teeth once a week or so. And still, I get a very dismissive statement from this ‘specialist’. What does the individual patient do when our physicians are so ill informed?

Who cares about all the research when it’s not getting to the medical community? Where do we go and who do we see?

Just incredible Katharine! There are hardly words to describe your experience.

I wonder how much the CDC multi-site ME/CFS expert study will help get the word and educate these doctors!

Health Rising will be providing an easier way to find doctors who know something about ME/CFS…

https://www.healthrising.org/forums/threads/potential-linking-rbc-glycolysis-air-hunger-thyroid-atp-dumping-pregnancy-improvement-and.6236/

Please note the information in dejurgen post and also the other link within this text. It addresses issues with hypoxia and other issues related to energy in the body. This post alone seems very significant to me!!!!!

Good work dejurgen!!!

If any researcher reads this, I believe it would be very very interesting to try and zoom in on the role of 2,3-Bisphosphoglycerate https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2%2C3-Bisphosphoglyceric_acid in the RBC themselves.

This little known chemical can be formed from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1,3-Bisphosphoglyceric_acid.

1,3-Bisphosphoglyceric acid is an intermediate in the glycolysis process. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Glycolysis is the process in which glucose converts into pyruvate and produces a modest amount of ATP in the process.

As such, glycolysis is vital to convert glucose to pyruvate for the mitochondria to use and hence for the bodies energy production. But most cells do have mitochondria. RBC need to be small enough to flow easily enough trough small blood vessels. Therefore they don’t have mitochondria. As such, they depend vitally on glycolysis to produce enough ATP for their functioning and their very own survival.

Yet, it are those RBC (and the placenta of pregnant women) that can produce this 2,3-Bisphosphoglycerate intermediate in the glycolysis chain. In such, they divert some of the very much needed energy production. That asks for a clear why.

It appears that this 2,3-Bisphosphoglycerate chemical very strongly modulates how much affinity RBC show for oxygen or in other words how willing they are to release their oxygen. Low amounts of 2,3-Bisphosphoglycerate mean that the RBC will cling very hard on to their oxygen, while high amounts of 2,3-Bisphosphoglycerate mean that they will release it easily.

This 2,3-Bisphosphoglycerate chemical however can be either stored in the RBC, helping to better release oxygen, or converted to https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/3-Phosphoglyceric_acid. 3-Phosphoglyceric acid is another intermediate of the glycolysis chain. So converting some of the “stash” of 2,3-Bisphosphoglycerate that the RBC have to 3-Phosphoglyceric acid will produce extra ATP for the RBC but it will decrease the ability for the RBC to release its oxygen as there is less 2,3-Bisphosphoglycerate left in the RBC and that makes RBC cling on more tight to their oxygen.

So when somehow RBC are depleted of energy, they have to make a choice to use their “stash” of 2,3-Bisphosphoglycerate as a sort of private emergency fuel and convert it into ATP for their very own survival BUT lose much of their ability to release oxygen and thereby hurt almost all other cells in the process OR prioritize oxygenation of the other cells by keeping enough 2,3-Bisphosphoglycerate in store to do this but risk the chance to cause themselves extensive damage or die quickly.

So basically when the speed of glycolysis falls down body wide, as is more then once observed in ME/CFS, then the speed at which RBC can generate energy for their own survival falls down. If that gets too low, they have to scale back on releasing oxygen in favor of their own survival. But that leaves much of the other tissue deprived from oxygen. In the absence of enough oxygen, the flow of pyruvate to the mitochondria must be reduced in order to not create copious amounts of ROS. That can be done by further slowing down glycolysis. We have a clear potential for a vicious circle here.

DeJurgen’s back! 🙂

Dejurgen and Issie are back. Don’t forget Issie pioneered new insights in POTS and MCAS many years ago and was able to put it on the radar of many clinicians.

She is every bit as important to developing these new ideas as I am. Different skill set, different insights, different main symptoms but both being oh so complementary. It’s bringing the two of us together that pushed us both beyond our individual limits. The joys of cooperation!

The idea of the importance of 2,3-Bisphosphoglycerate also could explain why ME cells dump part of their very hard won ATP into the bloodstream.

That is according to Ron Davis something that is unique to ME. Why would our cells do this if they already lack energy so much?

One explanation could be that the cells studied that show this behavior are all cells with mitochondria as far as I know. They can, when having enough oxygen, produce far more ATP out of one molecule glucose then can be produced by the RBC through glycolysis. The difference is about a factor of 10.

So if the (non RBC) cells starving from oxygen somehow “know” that the RBC still have plenty of oxygen but wont release it, then they could “know” that the RBC are starved for energy and can’t release oxygen therefore.

So they send some of the ATP they produce in the bloodstream for the RBC to pick up. Then the RBC can release more oxygen. And the cells receiving that oxygen can produce much more ATP per molecule of glucose then the RBC can, so they can “afford” to dump a reasonable amount of ATP in the bloodstream as that will increase the release of oxygen more then enough to compensate for the lost ATP.

It would be sort of a trade of the cells to dump some ATP in the bloodstream: we’ll give the RBC some of our ATP if they give us more oxygen.

Fascinating. Hope some researcher(s) will be motivated to write the necessary grant proposal(s) to look into this.

This chemical also could help explain why so much pregnant women have a strong temporary reduction in ME symptoms. The only other known human cells that can produce this 2,3-Bisphosphoglyceric acid molecule are in the placenta. Pregnant women produce up to 30% more of it, making oxygen release from the RBC so much easier.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2%2C3-Bisphosphoglyceric_acid: “In pregnant women, there is a 30% increase in intracellular 2,3-BPG.”

It is a complex method to help get the fetus more oxygen. I wrote more about this and the other mentioned topics in https://www.healthrising.org/forums/threads/potential-linking-rbc-glycolysis-air-hunger-thyroid-atp-dumping-pregnancy-improvement-and.6236/. It gets (more then) a bit technical however.

Wow…..two friends with ME have said they were nearly asymptomatic during pregnancy, but within a month of giving birth everything was back with a vengeance. (Can not imagine caring for a newborn while struggling with ME!) Very very interesting, DeJurgen! Could something be safely done to trick the body into ‘thinking’ it was pregnant and thus reduce symptoms?

“Could something be safely done to trick the body into ‘thinking’ it was pregnant and thus reduce symptoms?”

That is something we’d like to see professional researchers pick up. It’s far too tricky to try and do that as an individual it seems. But it opens routes for research for both better understanding the very nature of ME and potential treatment.

However I heard of the “coming back with a vengeance” thing too. Care would have to be taken on long term safety of doing so. Improving illness this way might mask some underlying causes that beg for treatment. If so, both should be done!

There is more to this chemical. Thyroid hormone supplementation has been a subject of debate for decades in ME.

Many (but far from all) patients with “in range” thyroid values seem to benefit from thyroid hormone supplementation. Many of us know people who benefit, sometimes to very large and obvious degree.

On the one hand there is a group of patients and their doctors willing to stand strongly by it. They say that “in range” is not specific enough taking diverse patients into account and that the difference between active and non-active thyroid hormone should be more taken into account.

On the other hand there is a large group of highly trained medical experts say that it is total nonsense and dangerous to supply these patients with thyroid hormones.

Well, maybe BOTH could be right. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2%2C3-Bisphosphoglyceric_acid:

” Hyperthyroidism

A 2004 study checked the effects of thyroid hormone on 2,3-BPG levels. The result was that the hyperthyroidism modulates in vivo 2,3-BPG content in erythrocytes by changes in the expression of phosphoglycerate mutase (PGM) and 2,3-BPG synthase. This result shows that the increase in the 2,3-BPG content of erythrocytes observed in hyperthyroidism doesn’t depend on any variation in the rate of circulating hemoglobin, but seems to be a direct consequence of the stimulating effect of thyroid hormones on erythrocyte glycolytic activity.[3] ”

Maybe the specialist are right that it risks getting “in range” patients to a (near) hyperthyroid situation. And patients and their doctors are right that it improves many of their patients a lot.

Both can go hand in hand as a slight form of hyperthyroidism increases this so important 2,3-BPG chemical in the RBC and helps to alleviate the so very important oxygen release bottleneck in ME by increasing the production of the chemical that helps release oxygen from the RBC.

The clear risk here is that RBC then could starve from ATP because if they produce more 2,3-BPG and keep a higher buffer of it, then they can (temporarily) produce less ATP for themselves. But the cells can produce more ATP and release more of it in the bloodstream to support the RBC if needed. And over time this *could* (in some patients) help break the vicious circle through better cell oxygenation.

Now this is very early and I do hesitate to post it, but I feel it is important if researchers would read this and doubt to include researching this idea.

Issie and I are for some time trying to alleviate this bottleneck. So far, based on this very idea, we identified a way to improve our breathing quite a bit. We feel we have more oxygen available to our tissues, have less air hunger, must breath less deep yet still feel like we are breathing well.

Then why do I hesitate to write about it yet? It is unfortunately not easy to avoid side effects at all and we first wish to try and improve our knowledge about what we are doing and how we can get it more stable. For if not, we’ll only get patients sicker as it’s pretty damn difficult to get it right.

But our attempts demonstrate that this (the problem with this 2,3-BPG chemical in the RBC ) *could* be indeed an important or even core part of ME. But we all know how much can go wrong.

And please do not try and fix this problem yourself!!! You’ll risk for example bad reperfusion damage or extensive damage to the RBC if you don’t get it right. And getting it right is though!!!

Note also that we believe this is not the cause of ME, but a “locking in mechanism”. We believe many many patients have ongoing issues requiring this *!*protective*!* mechanism to be active so identifying and reducing those is of vital importance before trying to unlock this security mechanism.

That also holds for viral onset patients who see nothing else but a viral onset being the cause of their disease. Most very likely had hidden weaknesses before getting ill that are triggered now and need to be target before unlocking the safety mechanism.

In the eventual case professional researchers were interested, ask Cort to forward a mail to me.

Our research and self experiments seems to be of significance and promising. We both find benefit. But as dejurgen said……it is very hard to stablize and moderate. And not without side affects that we don’t quite have figured out yet.

Hoping we can help find some of the pieces to this puzzle.

We have several things we are exploring.

Thanks dejurgen for posting and putting it out there. Hoping for researchers to pick it up and carry it forward.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Myoglobin, an important carrier of oxygen in muscle tissue is not affected by https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2%2C3-Bisphosphoglyceric_acid:

“In contrast, 2,3-BPG has no effect on the related compound myoglobin.”

But myoglobin gets its oxygen transferred to it by hemoglobin. So if hemoglobin releases its oxygen slower (or in other words hemoglobin clings on to its oxygen) then different options can arise:

A) Blood flows at a normal rate in and near muscle tissue. The amount of time hemoglobin and myoglobin (the main oxygen carrier for muscles) “spent” together is the same in these patients as it is in healthy people. But the transfer from oxygen from hemoglobin to myoglobin is a lot slower.

That in practice will make that few oxygen molecules “have the time” to “hop” from hemoglobin to myoglobin. As a result the hemoglobin will return to the heart and lungs packed with oxygen but the muscles will be left with few oxygenated myoglobin and hence be low on oxygen supply.

=> This resembles Corts “High-Flow (Low Oxygen)” model a lot.

B) Blood flow goes at a slow rate in the “main” blood circulation. The time any amount of blood spends in or near the muscle tissue is a lot longer due to the slow flow now. Even if hemoglobine binds to oxygen a lot more then in healthy people, enough oxygen will make the “hop” from hemoglobine to myoglobine allowing a greater part of hemoglobines oxygen to be given to the muscle tissue.

This in practice will make that the RBC will return to the heart and lungs with lower (normal for healthy people) amounts of oxygen left. But, if flow of blood is low enough then the capacity of distributing oxygen throughout the body including to the muscles is limited just because fewer RBC per minute pass by the heart and lungs. So its not an ideal situation either.

=> This resembles a lot Corts “Low Flow (Normal Oxygen)” model

C) Anything in between it.

Note 1:

This division between A) and B) *may* be part of how patients get divided between FM and ME if my intuition is right. Very preliminary however. Reason to think so: brains don’t have myoglobin so optimizing for better transfer to myoglobin could go at the cost of decreasing blood flow to the brain.

Note 2:

This slow transfer of oxygen from hemoglobin to myoglobin (in both cases A) and B)) due to 2,3-BPG problems could also help explain why many of us have a very short buffer of muscle energy: if we rest long enough the muscles have time to “recharge” their myoglobin. When we start to exercise however this “battery” gets depleted very quickly and we have a very poor “provision to the main lines”.

One could compare it a bit with having a lawn mower that can operate both on battery power and mains power. With it having a good quality large battery but only a very poor mains cable able to provide it with a low current. As long as the battery is full enough, the mower will work fine. When it has to draw power from the mains cable, it falls flat. But recharging it with an appropriate battery loader over night and continuing work tomorrow will work with that tiny cable.

Here, the limited cable is the slow transfer from oxygen from hemoglobine to myoglobine.

Possibly your best ideas yet Dejurgen. I was unaware of the low oxygen, high blood flow scenario until now. Does this explain why not every patient who suffers from ME has low blood pressure and why some actually experience high blood pressure? It is not something I have ever been able to understand and I actually feel quite a profound sense of relief about how well that scenario fits for me. Despite experiencing profound PEM and all other symptoms commonly associated with ME, my blood pressure has always been fairly normal, albeit my heart does strange things and my bp can spike very high if I try and push through a crash. On some level it has always made me wonder where I fit into the bigger picture. This probably explains why I do well with breathing exercises and have had significant improvement on supplements that target high oxidative stress. I have always wondered if the blood pressure thing had anything to do with whether a patient develops glucocorticoid sensitivity or resistance. I have experienced odd wee symptoms of gc resistance ever since I got sick at age 18

Think about this as a possible explanation for different subsets of POTS. That being a blood flow problem and inability of getting oxygen and blood to the heart and head.

The more common form of POTS has lower blood pressures to start with. And the HyperPOTS form, that I have, has higher blood pressure. We both have issues with the much needed oxygen to where it counts…..heart and head.

Some of us have found we do better with slightly vasodilating too. Rather than a traditional treatment of vasoconstriction of blood vessels.

Different subsets, but this has potential to help both types.

Patients? Will they or are they seeing patients?

I think Felsenstein – part of the group – has seen ME/CFS patients for many years. Otherwise I don’t think ME/CFS patients make up a core group of any of the other specialties. Patients have find their way in there one way or another and get treated.

I think this is something the Tompkins wants to change. He’s starting out with this group of interested doctors. For one he wants a clear path for ME/CFS patients – standard diagnostic tests, referrals to right physicians who give the right tests. Ultimately he wants a Center of Excellence that can see many patients.

There is no Center now and Tompkins said didn’t want to give the impression Harvard is set up to see and adequately care for large numbers of patients. Unfortunately, it is not. That will take quite some time.

And maybe, just maybe, the “Harvard-of-the-West” will feel competitive enough to fund a similar effort with Ron Davis. It wouldn’t be the first time that Stanford got embarrassed into doing something because Harvard was doing it.

Let’s hope. A blog is coming up on what’s going on with the Stanford situation. I think Tompkins and Xiao are in some ways in a better situation and in some ways not. Stanford has had an ME/CFS clinic – so it has a head start there but I was really surprised at the number of specialists Tompkins found at the Harvard hospitals that were interested in ME/CFS.

Thank you for sharing info on this horrible disease. I was “hit” by it in the morning of April 12,1998. I would not wish this on anyone.

Nora, you’ve been sick a long time. I was also hit, very suddenly in Sept of ’08. Working one moment, next moment couldn’t think about what I needed to do in my work as an account manager, and went to hospital fearing a stroke. Fibro/ME (I’m utterly convinced they are very closely related conditions), 70% drop in income when I went on SSDI, funds for altenative therapies or many supps. The one thing that has helped is K PAX Immune Support as it targets the mitochondria, and I believe mitochondrial dysfunction is big part of the picture with ME.

Hi Cory, thanks for this optimistic update. FYI – David Systrom is not in the picture. I saw him for the first time in September and have a follow up appointment with him in January to do his invasive CPET. He explained that, after the test, the results will be sent to my PCP, and DS will consult with him re: treatment. But DS patient roster is full and he won’t see me as an ongoing patient. I’m in NH – about 1 1/2 hrs from Boston – and will follow the developments at Harvard closely.

Thanks Jody. I think this is precisely why we need a COE. I don’t know if anyone can replicate Systrom’s work – he’s ploughing new ground all the time – but a COE would certainly have an exercise physiologist that could see and monitor patients. Exercise is after all a crucial stressor used in many studies: every Center of Excellence for ME/CFS should have one for its research studies alone.

Good luck with the iCEPT….Glad you’re able to at least get in there.

Can the fact that a 2-Day CPET does not pass an initial IRB review at Harvard/Mass General please create some precedent?!

Hi Cort, Thanks so much for including “The Gist” for part of this article! It’s so appreciated by those of us who are limited in the amount we can read.

I wish there could also be summaries for the comments of members who have very complicated theories. I’d like to profit from their work, but alas, can’t hope to process and retain that amount of detailed information.

I just started really ACCEPTING that I’m cognitively disabled now. Before I became ill that type of information would not have been a problem for me 🙁

I wish I could stay on top of things enough to try treatments that others are trying, but I can’t think through them and do the research anymore. Now I’m just hanging in there and hoping that someone tells me when they figure it out. 😉

“I wish there could also be summaries for the comments of members who have very complicated theories.”

That could fit me. For now:

Issie and I may have found a chemical typical to Red Blood Cells that helps a whole lot with the RBC giving their oxygen to the rest of the body. But when the RBC can’t produce enough energy, they can’t produce enough of this chemical.

If the production of this chemical goes wrong, it can create or strengthen a nasty vicious circle. We have seen an option to try and break that part of the vicious circle. We now both can breath better and have *at times* clearly more energy. But it still is kind of a minefield. One wrong step and we are worse off for several days.

We also need to learn if it is safe to break open that vicious circle. It could be a safety measure protecting us.

So it’s not stable or ready to be released. We have to be very careful not to set ourselves months back. We can’t risk that other patients go in head first with far less precautions then we take now. But we are tying to see if we can get it more safe, stable and reliable.

Then and only then we can tell what we do and how we try to make it more reliable and tell so in plain words. Having some professional researchers helping us to get it work better and safer would help too.

Hang on Birdie. For now we only can offer some hope.

Oh dejurgen, thanks so much for your summary!! I understood that and it gave me hope 🙂

Also, sincere thanks to you and Issie for your work to help us all. Best wishes, but please take care of yourselves.

dejurgen – I am dealing with many things as best I can given my cfs. I am reasonably certain of that diagnosis given the negative results of all the tests I have had, the aha moment both myself and wife had when we read about PEM as we are about cfs. And I then had a 2-day CPET given by Workwell.

Unfortunately, I seem to be in a few desert. No doctors anywhere nearby. I graduated magna cum laude from Ivy League university with B.S.E. bioengineering (with emphasis in electrical engineering). And the Ph.D. chemical engineering from M.I.T. Then after a brief postdoc, more than 20 years as environmental consultant.

I say all this to convince you I know how to do scientific research correctly. And to offer / ask to aid you in any research you might think is appropriate. We both know larger sample sizes make for better science. Not certain how best to communicate. Let me know if you have suggestion.

Hi Birdie,

Like you, my brain just doesn’t work with the speed and clarity it used to. But the way I see my current situation is, instead of holding lots of different concepts in my mind at once, I’ll just focus on what’s happening now. It makes things so much easier.

It has been very challenging over the years to try and work out what’s going on with my health with a malfunctioning brain and a terrible memory, whilst others were trying to convince me there was nothing wrong with me.

My brain function and memory are improving but still, I know myself, there’s a loss of organisational abilities that I would have been good at before, that are diminished.

However, I do sense that there is a level of momentum building, with people like Ron Tompkins attracting doctors to gather together. I think it’s just early days. The best we can do, as you say, is hang in there…

I don’t know exactly why I don’t function as well as I used to. I have found things that help me function better and I’m hoping that at some point in the future this will all make more sense.

I’m not scientific and certainly don’t understand the more complicated pieces and feel a bit overwhelmed at times. I just read what I can and go at my own pace, which is fairly slow…

But I do feel encouraged and believe there seems to be a growing number of really very creative and inspirational people out there who are interested in helping people like us. ?

Tracey

Hi Birdie, Dejurgen, Issie and Nancy B, thought I’d have a meander around info online on traumatic brain injury and inflammation.

It made sobering reading but also seemed to be discussing the areas you’ve been looking at.

Brain issues are currently my most challenging symptoms. I’m sleeping much better, every night, which helps everything as I’m not experiencing the level of exhaustion I once did. My diet seems to be supportive and I appear to need a good supply of protein – particularly animal protein (sorry animals). If I don’t antagonise my immune system I can function fairly well. That ‘just’ leaves that super complex interconnected multi-purpose system housed within my skull.

I try and respond to what my brain needs, as I do believe my body and mind are always trying their best to optimize my survival, even if at times it doesn’t feel like that is the case.

Anyway I don’t want to be alarmist but I think those of us who have noticeable brain function issues are already dealing with this on a daily basis anyway…

Tracey

Well, here’s an idea. If Thompkins really wants to think “BIG”, Harvard is only one of four Medical Schools in Boston that are ranked in the top 50 in the US. Why not try to involve UMass, Tufts, and Boston University as well? The schools are notorious for collaboration on studies and Harvard is just the one most people know of, but now but clearly not the only excellent one!

Cort, dejurgen and Issie, thanks so much. Very interesting read, good explanations. It gives us all hope and just knowing that research is amping up really helps. Hopefully governments will step up the research funding. Patients paying for research is such a burden when many cannot work.

It is. I’m thankful we’re doing what we’re doing. I still wish, though, for a mega donor to step up and put his/her name on a building – what a legacy that would be (!) – or pump $50 or 100 million into research or advocacy. Autism really got going when a smart donor decided to put scads of money into advocacy and it worked. Research funding grew enormously.

Wow, finally a bit more research momentum! And Dejurgen, you are really on some kind of theoretical explosion! Indeed, welcome back! I will have to take some time to go through all the links and think about stuff…

The day before Thanksgiving, I had my appointment at Stanford’s CFS clinic, which I described in Cort’s ‘Solid Ground At Last/Cytokine’ post comment section. Dr. Bonilla is now convinced that there is a problem with the mitochondrial membranes which somehow involves faulty TSPO messaging–as well as neuroinflammation–and not so much cytokines. He thinks the membranes are not letting in ‘?’ (Dr. Bonilla is hard to understand at times) which limits the energy the mitochondria can produce. He scrawled a huge mitochondria ‘cartoon’ on the tissue I was sitting on which appeared to have ‘H+’s enclosed in the interior of the cell, and ‘ATP-Stc’ on the edge of the DNA and then ATP with an up arrow in the middle of all of this. He doesn’t allow any recordings, so I can’t re-listen to try to make heads or tails of all of this…

I do wonder if that could tie into your theory, Dejurgen…

I’m still on micro-dosing of Ability, but after the meeting, (and my apologies for my limited science background), I am trying yet another supplement which supposedly targets those membranes–NT Factors. I realize this is kind of a ‘buzz word’, (and many of the ingredients are ‘proprietary’ but essentially are various phospholipid complexes) but what the hell?!

Dejurgen, I’m very interested in what you and Issie are cooking up!

My having severe mitrochondrial dysfunction myself…….its on our radar.

Hi Nancy, sorry for the late reply. I looked into it earlier but didn’t got very far.

If attaching files is difficult, maybe try on one of these links on the forum where it fits most. It’s easier to attach files on the forum.

https://www.healthrising.org/forums/threads/potential-linking-fm-mast-cells-sleep-deprivation-food-intolerance-exercise-intolerance-and-me.6217/

https://www.healthrising.org/forums/threads/potential-linking-rbc-glycolysis-air-hunger-thyroid-atp-dumping-pregnancy-improvement-and.6236/

Let’s go to… _Melinda_ Gates. Melinda Gates. Just circling back to the Bill Gates suggestions. Mr. & Mrs. Gates really are at their best philanthropy as a couple.

Nancy B., just wondering, do you still have the drawing that Dr. Bonilla did? If not, no worries, I’m trying to picture that, yet I wouldn’t have thought to save it if I’d been there myself.

Meanwhile- please can anyone here recreate that drawing and-or related drawings? Cort? DeJurgen?

@ElizabethKay,

Yes, I still have the ‘cartoon’. The NP thought it odd when I tore out the drawing to take home–so I do have it.

I, being an Internet Neanderthal, don’t know how to send it. I don’t have a smart phone, and I don’t see a way to add an attachment to the comment section.

Anyway, it is kind of a scrawly diagram, not exactly the quality clue you may be looking for…

Standardizing diagnoses and protocols seems so basic… but glad it’s finally being addressed. Another thought… what collaborative approach was taken/what factors contributed to the amazing advances in AIDS/HIV we’ve seen in the last 35 years. Can this be studied and duplicated? It’s a combination of politics, fear, shame, funding, dedication, etc. We need more celebrity spokespeople, sadly we don’t have anyone with the level of influence of a Liz Taylor… On finding a cure – Anyone with CFS and Fibro surely must suspect that a pathogen is at the root of all of it, even leading to CCI type issues (we universally have weak neck muscles, from what I understand). Would love to see a focus on finding and killing the pathogen which is probably at the root of this bizarre disease! In the past this has seemed to be so rife with politics and even possible government cover ups! Once the bug is identified… Toxins like mercury only create an unstable environment in which opportunistic infections can thrive… Hopefully we can learn from all prior top researchers and patients as well. Rambling I guess, but sometimes that’s all we CFS/FM patients can do.

Linda – You may not be familiar with the work of Naviaux at UCSD. Using some new method to look at the hundreds of metabolic pathways in cells, he has identified a handful that are significantly different than normal. And he has matched these to a known hibernation-like state. Consequently, his theory is that humans that – that are susceptible – that are subjected to an unrelenting stressor slip into this state. So the stressor could be infection and/or combined with other stressors. This makes a lot of sense to me because different researchers have had some success looking for infections, but have been different infectious diseases! And some people with cfs don’t seem to have any infection. ALSO – if you follow modern cellular biology, what was once called “junk dna” that separates the identified genes on the chromosomes has been found to really be “switches” that respond to different environmental conditions. Depending on conditions they switch on or switch off the genes next to them! So, seems reasonable that some of us are more susceptible to its that others (just like with many other medical conditions), and if we experience unrelenting stress, then some hibernation-like genes get turned on. Given humans don’t normally hibernate, figuring out how to switch these genes back off is the million dollar question. Here is link to interview with Dr. Naviaux. https://www.omf.ngo/2016/09/09/updated-metabolic-features-of-chronic-fatigue-syndrome-q-a-with-robert-naviaux-md/

Does this good news translate beyond the research to the possibility of getting clinical diagnostic work in these areas? I’m considering going to the Brigham and Women’s Autonomic Dysfunction center for diagnosis of my orthostatic intolerance, collapses brought on by exertion, etc. Do you think I’d be able to get access to these doctors and tests at the same time? Also, do you, Cort, or anyone know the best place to go for really good, inter-disciplinary diagnostics on autonomic dysfunction? I’ve just learned about the venters at Banferbilt, NYU Langone and Harvard Medical (different from B&w I think. I’d love some suggestions especially from anyone who’s been through this kind of center. Thanks to cort and all!

FM 25+ years…….I’m encouraged for the first time since reading about this research and hoping and praying the funding continues.

This is incredibly exciting. Please know that patients like me are still VERY eager for answers and more research to be performed. My exercise intolerance has ruined my daily life as well as my athletic career. Feeling like my chest will explode if I exercise a little bit makes me feel like death and that I’m far older than 20s.