Travis Craddock heads Dr. Klimas’s biocomputational modeling team at the Institute for Neuroimmune Medicine (INIM) at Nova Southeastern University. This is the team responsible for crunching the hundreds of thousands of data points gathered from Dr. Klimas’s intensive exercise studies into a massive model of how the immune, neuroendocrine and other systems interact in the body.

It’s takes a village – a research group of biocomputational experts – and in this case, a supercomputer. It was this team and their work which Dr. Klimas used to gather some monster Gulf War Illness (GWI) grants and design some novel clinical trials.

The study was different in several ways The team dove headfirst into a pile of genetic data and emerged with something completely out of the blue. Something which could make you rethink this disease.

Plus Craddock et. al. didn’t use a dataset that cost $100,000 to produce. The genetic data that produced this surprise finding was a generous gift from the ME/CFS community.

“The Great Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Community Gene Study” which produced the data (known to the people who created it as the “ME/CFS Genetic Database Study”), consisted entirely of genetic information provided by patients from their 23andMe or Ancestry.com datasets. It came out of a community project launched by Dr. Klimas’s team.

Craddock spoke about his early results about 1 hour and 55 minutes into INIM’s recent 3-hour webinar.

Feeling Phlegmy?

The study had already found evidence of a heritable defect in the methylfolate (MTHFR) gene in ME/CFS. That wasn’t entirely unexpected but no one anticipated the sticky situation which turned up in the latest analysis.

A remarkably large proportion (77-80%) of individuals with ME/CFS were found to have alterations in the genes that produce mucous. Yes, mucus. Gooey, gummy, gloopy mucous – in scientific terms, a “complex dilute aqueous viscoelastic secretion” or “viscous gel” – otherwise known as phlegm. Mucous generally doesn’t get much respect but it actually plays a critical role in our health.

Mucous lines our nose, our airways, our gut, our eyes. It traps and provides a vital barrier against chemicals, viruses, molds. It also protects against dehydration, physical injury, etc. It also contain immune factors to fight off any nasty pathogens or mop up any toxins. Without our protective mucosal barriers, our bodies would be inundated with toxic or pathogenic substances.

Over 100 proteins are found in mucous, which make the concentration of defects Craddock found in ME/CFS – all in the genes that produce the mucus 19 proteins – rather noteworthy.

Small alterations in these genes have been tentatively associated with Sjogren’s Syndrome – which some believe is dramatically underdiagnosed disease in postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) and allied disorders – as well as in Crohn’s disease and asthma.

There are alterations in genes and then there are ALTERATIONS. Most small genetic changes make little or no difference. Others dramatically change the functioning of the protein they produce. One of the genetic alterations fell into the latter category. It was about as deleterious as a genetic alteration can get: people with this gene (I couldn’t tell what percentage of patients had it) produce a puny, truncated, probably wholly dysfunctional protein that is a third the size of normal.

Back to Baraniuk

This isn’t the first time, though, that ME/CFS researchers have given the nose a sniff. About a decade ago, James Baraniuk spent several years probing, tweaking and trying to understand what was going in the nasal passages of people with ME/CFS.

Baraniuk found that sinus pain and non-allergenic rhinitis were present in a substantial number of people with ME/CFS. In fact, the mid-facial regions of people with ME/CFS were more painful than people with documented physical abnormalities such as allergic rhinitis or rhinosinusitis.

Many people probably mistake the symptoms of mid-facial pain (nasal pressure, heaviness, tightness, nasal blockage) for tension-type headaches. The pain is generally symmetrical, affects both sides of the face and usually has no clear exacerbating factors. Analgesics, antibiotics, and intranasal steroids are usually ineffective.

Baraniuk was unable to find any evidence of swelling or blockages in the noses of ME/CFS patients that could explain the feelings of pain, heaviness and congestion they typically experienced. Nor was he able to find any signs of inflammation (total protein, NGF, TNF-a, IL-8), mast cell activation or an allergic reaction (increased IgE levels) that could explain why the middle area of their faces were so sensitive.

Baraniuk concluded that most people with these diseases were suffering from something called idiopathic nonallergic rhinitis (iNAR).

Small Fiber Polyneuropathy (SFPN) Connection?

Eight years ago, long before the SFPN news in FM hit the fan, Dr. Baraniuk asserted that damage to these same small nerve fibers (type C neurons) was causing the mid-facial pain he’d found in ME/CFS.

He proposed that hyper-active (TRPV1) ion channels on the nerves in the nose were sending an unrelenting stream of signals to the parts of the brain involved in processing pain. Over time this resulted in central sensitization – an upregulation in the pain producing pathways and a downregulation in the pain inhibiting pathways in the brain.

Eventually, even minimal sensory inputs from the nose became translated by a centrally sensitized brain into sensations of pain, nasal heaviness and congestion – a congestion Baraniuk called “phantom nasal congestion” – which he likened to phantom limb pain.

Baraniuk went even further, though. Noting that a form of rhinitis called “dysautonomic rhinitis” was common in ME/CFS, Baraniuk even attempted to tie together autonomic issues caused by the brain stem with the dysregulated processor of sensory information – the thalamus – and the nose.

Baraniuk believed the same kind of rhinitis is found FM, migraines, Gulf War Illness, multiple chemical sensitivity, irritable bowel syndrome and interstitial cystitis. (All of these diseases, he noted, receive low funding from the NIH.)

A Genetic Link?

Eight years later, out pops mutations in genes that produce the protective mucous layers in the nose and other areas.

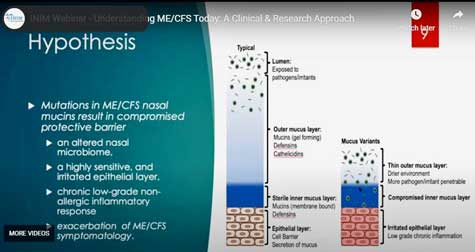

These 19 proteins form the outer gel layer of the mucous which prevents toxins, pathogens, and irritants from getting close to the skin layer where the nerves are.

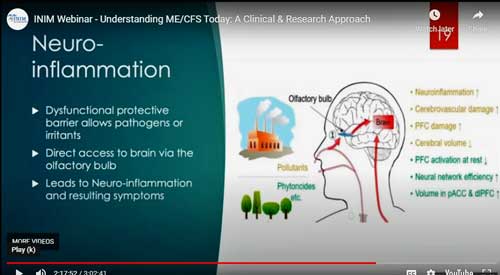

Craddock speculated whether a dysfunctional mucous layer might be contributing to neuroinflammation in ME/CFS.

Craddock proposed that the compromised gel layer could result in an altered microbiome in the nose, could be irritating the nasal membranes, and could be producing a chronic low grade non-allergic inflammatory response. The irritated nerves that result could produce increased sensitivity to chemicals often seen.

Craddock noted that a weakened mucous layer could allow pathogens, toxins and other compounds entry into the blood (leaky nose syndrome?) and producing a systemic reaction which flares up other ME/CFS symptoms.

Noting that the nasal microbiome is a hot topic right now, Craddock reported that, just like the gut, a healthy microbiome population in the nose plays a critical role in maintaining nasal health. Since the nasal microbiome is a reflection of the nasal environment, a compromised mucous layer would almost certainly result in an altered nasal microbiome. He speculated if the nasal microbiome in ME/CFS got impacted, perhaps by a bacterial infection, and was unable to return to health, it could leave the nose more sensitive to viruses and other pathogens and chemicals.

The Gist

- Nancy Klimas’s community-based and supported ME/CFS gene study produced a surprising finding: high rates of alterations in the genes that produce a particular kind of mucosal protein (mucous 19).

- At least one of these alterations has the potential to severely damage that protein – reducing it to a third of its ordinary size.

- Mucous 19 is involved in producing the gel layer that protects us from pathogens and toxins and which contains immune and other factors.

- Damaged mucosal layers in eyes, nose, and upper respiratory tracts could give pathogens and toxin easier entry into the body and perhaps, given the quick shot from the nose to the brain, into the brain.

- Systemic inflammation, neuroinflammation and central sensitization could all conceivably result.

- About ten years ago, Baraniuk’s studies on the nose found higher rates of mid-facial pain than in allergic rhinitis and sinusitis. He was unable, however, to find evidence of inflammation, mast activation, damage or any other potential cause.

- Baraniuk believed that the small nerve fibers in the noses of ME/CFS patients had been damaged and were sending a stream of pain signals to the brain – possibly causing or contributing to central sensitization.

- Craddock’s finding of altered genes that help to produce mucosal proteins in the nose provides a possible explanation for Baraniuk’s finding.

- Craddock hopes to expand his genetic studies, directly assess the microbiome and composition of the mucous in the noses of ME/CFS patients, expand his modeling studies, etc. to determine if this early finding checks out.

Craddock and his team – clearly excited by the their findings – have gone so far as to produce a logic model which tracked what would happen if someone with a compromised mucous layer allowed a pathogen to get across the gel layer. The model produced one healthy state (pathogen is fought off and everything returns to normal) and two unhealthy states – one of which included an innate immune system that is primed and ready to act up at the slightest stimuli. (That would include an over-activation of the NK cells (leading, one might think, to NK cell exhaustion and the reduced cytotoxicity found in ME/CFS.)

Another possibility, though, looms large – neuroinflammation. As Health Rising recently noted in a blog on using intranasal compounds to treat neuroinflammation and other brain issues, the nose provides pretty much a straight shot into the brain. Add a damaged mucosal protective layer in the nose, and an altered nasal microbiome with a quick pathway into the brain, and perhaps you have dangerous substances (pathogens, irritants, toxins) getting access to the brain and producing neuroinflammation.

It’s an intriguing hypothesis which needs a lot more validation. Craddock et. al. hope to perform more precise genetic analyses, examine the ME/CFS nasal microbiome, analyze the composition of mucous in the nose or the tears and improve the model they’re using.

Yes this just sounds right based on my symptoms.

“A secret set of salivary glands has been hiding behind the nose.”

This nasopharynx region — behind the nose — was not thought to host anything but microscopic, diffuse, salivary glands; but the newly discovered set are about 1.5 inches (3.9 centimeters) in length on average. Because of their location over a piece of cartilage called the torus tubarius, the discoverers of these new glands have dubbed them the tubarial salivary glands. The glands probably lubricate and moisten the upper throat behind the nose and mouth, the researchers wrote online Sept. 23 in the journal Radiotherapy and Oncology.

https://www.livescience.com/new-salivary-gland.html

I already know about a number of genetic mutations responsible for disabling symptoms in me. No surprise that there should be all these others as well. It is a complex condition, much of it apparently genetic in nature.

I really liked the possible small fiber connection….Could a damaged mucosal layer be allowing toxins or pathogens to short circuit the small nerve fibers in the nose? Interesting that small nerve fiber problems have been found in the eyes of FM patients as well.

When I first found the MCAS community after my ME/cfs specialist mentioned overlaps with symptoms of MCAS being common in her patients they introduced me to the concept of “leakers” (runny nose type) and “shockers” (anaphylaxis). Of course as time has gone on, I am not sure this patient model is common anymore inside the community- there’s definitely skin and GI MCAS symptom sets and people tend to be dominate in one or more. Not that its all MCAS related but let’s say the sinus issues don’t startle me at all having had major sinus issues and large amounts of drainage for years… enough to the point where I eventually wondered if I had a leak through my nose at some point. Makes me wonder just how many systems are potentially having “little” flaws all at once to create a perfect storm. Hope you are well Cort and thanks for your work here

Hi Shy,

Can you please point me towards more information on GI MCAS?

I was already in the more severe ME group and now I’m struggling to eat.

Any help appreciated. The simpler the better (if possible) because I’m unable to get through lengthy or complex information. THX!

Have you heard that there is going to be a very large genetic study carried out on the U.K.- led by the Iniversity of Edinburgh, Cort. I will see if I can find the contact and send this to him. Thanks for your hard work. My nose is always very wet during an ME flare up! Inside I mean!! Not running as much as wet and cold too! Like a dog!!

Like a dog!

I thought of DecodeME as I was writing this. Really amazing how much the UK is pouring into that study. We had a blog on it recently – https://www.healthrising.org/blog/2020/06/24/decodeme-genetic-chronic-fatigue-syndrome-uk/

Years ago Dr. Klimas and her team developed an excellent, easy-to-use online platform for patients esp. those homebound to participate in this Genetic Study. Nice to read about the important genetic findings in your outstanding blog, Cort.

Recently Dr. Klimas posted a short video describing how ME/CFS patients can protect their nasal passages from COVID-19 infection using OTC products (starts at 2:50 on the video):

https://www.nova.edu/nim/index?bclid=IwAR2WbE4DEHmv9KBYke_2RedBg61qHL7_SmJwmUIRyOjJM3Z7R1Bx57AE2ms

I may have missed this but what gene (s) is/are mutated? What is the name or identifier for the gene?

I didn’t catch the names of the genes with the polymorphisms. It looked like there were around five or six of them. Craddock, as I remember, referred to them on a slide. They all were associated with that mucin 19 protein.

The SNPs are all listed on the slide at 1:59:00 of the video.

https://youtu.be/QfrCF2atQxI?t=7140

It would be great if Cort (or someone he knows) could update this article or write a new explaining this chart and how to interpret it in regards to one’s genetic data. I can find the rs number in my data but it is not clear what the original/new amino acid columns mean for the most deleterious snp – rs10784618. Is CC normal and if even one letter is changed to any other amino acid it is abnormal? That is how I read it but it is confusing. Sometimes it is a lot worse if both letter are changed for a gene, sometimes not so much.

Thanks James for finding that and the great question! I will try and find out more. Maybe somebody else can help too.

Hey Cort…I pray your doing fine…Haven’t been on these blogs in a while…I might be one of the people who sent my 23&Me raw data to Dr.Klimas a few months ago…I have a big problem with excess mucous/phlegm on a daily basis since my ME/CFS got worse a few years ago…I’ve always had sinus issues since I was a kid…And since I was born with Bronchitis, I always had respiratory illnesses up until I reached middle age…Strange though, I haven’t had any real flu, colds, or Bronchitis since my ME/CFS got bad!…

As far as the SNP data that Mr. Craddock found, I have a Promethease Health Report doc of my 23&Me Raw data to see if I have a risk on those SNP’s….It use to cost $12 bucks to get a report if you send in your raw data…Now that MyHeritage.com owns them, I haven’t checked, but I believe they have kept it the same….It is a great informative report that SNPedia runs, giving you over 15,000 of your health related SNP’s and explaining them on the doc and also linking to the NCBI genome database…I’m not endorsing them, but letting your readers know this is one of the best ways to check for possible issues and mutations in their DNA if they have their raw data they can send…I hope this helps!…

Thanks Eric – good to see you back. For me – prominent mid-facial and head pain and seeming nasal congestion since I got ME/CFS. My head, neck, shoulders and upper chest are like a battleground. (Ouch!)

Like 5he sound of this.So very plausible for me given the mutation issue and neuropathy issues I have. Also wonder at the impact of trauma, in that I broke my nose at age nine, requiring cartlege removal, then two reconstructions in my mid teens (severe blood loss following the first saw the nose re-packed and misshapen, enquiring repeat surgery). each surgery cauterisation.

This is really interesting. Cort & readers: has anyone tried probiotic nasal sprays?

I know it can be dangerous to jump from hypothesis straight to “treatment” but this, at least on the surface, seems like a fairly harmless thing to try but I may be wrong. I have used oral probiotics for years (a good brand with multiple strains) as well as daily nasal irrigation as I have chronic sinusitis.

PS I’m a long-time reader but first-time commenter so if you’re not allowed to answer questions around meds / supplements, please disregard 🙂

The extent of this illness truly amazes me. There are just so many symptoms! For, 34 years now I’ve been describing to my doctors the constant pressure behind my eyes. They look at me incredulously, so I never bothered to complain about the burning eyes, the constantly running nose. It was hard enough to get them to understand the extent of the fatigue let alone bring up symptoms that were relatively mild. Now I’m wondering just how common these experiences must be among those with ME/CFS

Pressure behind the eyes could well be a sign of low thyroid levels that might require levothyroxine

Wow! How cool. It makes me think of Dr. Brewer’s protocol.

He was trying to figure out where in the body a fungi could set up shop and he speculated in the sinuses.

These are fascinating findings but I would disagree with one small detail that has a huge impact in our community.

“Craddock didn’t use a dataset that cost $100,000 to produce. The genetic data that produced this surprise finding came free of charge from the ME/CFS community.”

Free of charge to the researchers but paid out of the pockets of patients.

I am confident that soon our investment in our treatment will bring healing soon. Thanks for your continued reporting on our issues. I would give into despair without your work. Thank you!

Yes, better put – no cost to the researchers and thanks to the generosity of the ME/CFS patient community.

It doesn’t matter to me how much we all paid for our “Genetic Testing” because more than likely we all got it for free through our insurance (My insurance deemed it as medically necessary due to medicines not working and being so sick) or we paid 100 to have it done through another company, I’ve had mine done by 3 different companies because they all have a little something different about them and also 1 of my doctors I took results to a year later didn’t believe mine was true, he said there was no way possible someone could have as many genetic mutations as I have! Once the test came back and had the EXACT SAME RESULTS it was time to tell him goodbye for being a jerk and not believing me, like who the heck would make this crap up!!! Having genetic testing is so very important when you are so sick and it’s EXTREMELY HELPFUL knowing what mutations you have with certain medications (explains why some don’t work etc) and also tells you what diseases you have or could develop which is very helpful in EVERY ASPECT! Just as mentioned above promethius and a few other websites can be extremely helpful and dig way way deeper into your genes and tell you soooooo much more so it’s definitely worth it! So even though it was “free of charge” to the scientists for all of our information we should all be EXTREMELY happy that a scientist FINALLY did a gene study, which should have been done a decade ago! So I am extremely thankful to the scientists that spent all of their time and energy looking into this and doing their research which we would be screwed without them. So technically the study was not free at all because people need to be paid for their work gathering everything, inputting it into the computer, going through thousands of patients genetic tests and comparing everything then writing a paper about it and researching into the whole phlegm thing which I am sure was very time consuming considering our genetic testing was given to INIM over a year ago.

The results are VERY INTERESTING because I do have issues every morning when I wake up with a HUGE NASTY GLOB of it in my throat and have to hack it out like a man LOL it sounds absolutely disgusting!!! I PRAY TO GOD that this will bring answers to MECFS and be able to help us in some way come up with either treatment or a CURE. Thank you so much Cort for doing everything you do for all of us and thank you to the scientists who work so hard for this disease and never give up hope because without them most of us would have probably given up already!!!

Every new finding always makes total sense to people who have had this illness for years. This one fits perfectly into all the symptoms and diagnosis that have partnered with my ME through the years.

You mention the nose being a quick pathway to the brain. I wonder how all of this works for those of us who are very sensitive to perfumes, cleaning chemicals, etc. I wonder if it is the problem protein that allows these chemicals to reach our brains. In my case I can have mild anaphylactic shock from perfume (i.e. blood pressure drops so low that it doesn’t even register on the machine).

A prominent hypothesis in MCS or environmental illness is that the nerves in the nose have become hypersensitive to chemical signals. Problems with the protective mucous layers in the nose could cause that hypersensitivity to occur. Perhaps it could even contribute to small nerve fiber damage – another possible contributing factor.

Your blood pressure drop in indicative of a problem with autonomic nervous system functioning. Baraniuk found that his ME/CFS/FM patients had a kind of autonomic rhinitis I think it was – a distinct kind of nasal issue which was associated with autonomic nervous system issues. You appear to fit that profile very well. The small nerve fibers, by the way, transit both sensory and autonomic nervous system signals.

It’s kind of amazing how many different pieces of what we know about ME/cFS might be showing up in the nose: possibly small nerve fiber problems, autonomic nervous system problems, chemical sensitivities, neuroinflammation, central sensitization (???). Time will tell.

Thank you so much Cort!

I was very excited to hear about this research. I’m so sensitive to scents and chemicals in the air. A lack of mucus explains a lot.

I have indeed had very dry eyes for a long time, probably because of the thin fiber neuropathy. but also very often in the rear part of the nose mucus buildup which gets stuck. and sometimes just runny noses I think of hay fever.

Hi Cort, do you know if Nancy wants more 23 and me reports for the future?

I believe she does. Certainly they want to do more genetic analyses. I believe the community gene project is still open for business. I will try to find out.

Thank you! I’m happy to share my report.

Makes me wonder if burning tongue (mouth) syndrome could be related to this. They have not been able to figure out why that goes on for years in some people.

I don’t know but nerve damage can cause burning sensations.

Thanks for this info Cort.

I don’t get pain in my face but had bronchitis regularly as a child. Then asthma developed in my 20’s and it worsened in line with the ME /CFS symptoms.

I have to take antihistamines every day throughout the year as well as strong steroid-based inhalers to keep asthma in check.

Before I developed ME/CFS my doctor said I had virus-related asthma – ie I got asthma when I had a cold or flu (rather than through an allergy) . Though I also get breathing problems if cold air gets in my lungs.

Now I’m beginning to wonder if all this is actually connected with ME/CFS and that wonky gene.

There isn’t any disease called ME/CFS/PVFS. It is a misdiagnosis. Many people with ME/CFS/PVFS have had to take supra doses of T4 or T3 to become well. ME/CFS/PVFS is just a hormone deficiency and even if you take the hormones, you may not be getting enough into your cells so you just think to yourself, “Well I can’t be hypothyroid then.”

Just keep trying to put more into your cells and get well. As an example, I had symptoms come back recently and so I have recently been taking B12 supplements and now all my symptoms have vanished. LOL. Another example is Jen Brea. She had a thyroid problem and after taking thyroid medication for a while she has recovered from severe ME. it was nothing to do with EDS or CCI like she likes to claim. If it was, everyone would be able to get well with CCI surgery but the thyroid was her problem just like most people’s with ME/CFS/PVFS. Thanks

https://www.tpauk.com/main/article/transcripts-of-the-gmc-hearings-relating-to-the-late-dr-gordon-skinner/

The above transcripts are all the help anyone with ME/CFS/PVFS needs.

That is Amazing News! I can totally relate to their finding as well as my family history!

Hope to see some treatments coming soon..

Thanks Cort for bringing this Ray of Hope and thankx to ME/CFS Community, Dr. Kilma, Craddock and all others in involved!

Thanks for a very interesting blog!

Always a stuffy nose, and nothing helps.

But what about the lungs?

Shotness of breath, a feeling of not getting enough air etc. are common ME symptoms. Has anyone ever looked at phlegm in the lungs in the mornings?

This is very interesting! I sent my data to the scientists a year ago.

If I can’t find a certain rs number in my raw data. what does that mean Cort?

Best, Lieke

I’m afraid I have no idea! 🙁

I was in that study, so I just checked my 23andMe data, and sure enough, I’m homozygous for the most damaging SNP mentioned in the presentation. Maybe finally an explanation for The chronic middle ear problems. This is fascinating, thanks for bringing to our attention Cort.

I am amazed at all the comments concerning nasal issues and ME/CFS. I suffer from drainage issues along with dry mouth constantly. Thank you for all the information posted! God bless your research!!

Following blood tests that showed an immune response to strep, my doctor concluded that strep was passing from my nose to my gut.

After reading this, perhaps the strep is entering the bloodstream via a compromised mucosal layer within the nose? Interesting stuff. An ENT recently examined my nose/sinuses to find chronic inflammation inside the nose.

What an amazing discovery! Hope returns, and all that.

And it has me wondering about a possible connection with fine particulate matter, from air pollution, entering the brain. Presumably, if the mucus does form part of what barrier there is, in the nasal route into the brain, it being deficient would allow more particulate matter in. And FPM would be a particularly-persistent source of toxins and inflammation.

From a recent review of the science regarding FPM as a cause of Alzheimer’s, particularly regarding this hole in the blood-brain barrier (SciAm: “The New Alzheimer’s–Air Pollution Link”, by Ellen Ruppel Shell) :

“Unfortunately, there is now compelling evidence that PM 2.5 can and does enter the brain via two pathways. First, the particles can alter the blood-brain barrier itself to make it more permeable to pollutants. Second, the particles can bypass the barrier altogether by slipping from the nose into the olfactory nerves and then traveling to a part of the brain called the olfactory bulb. The brain, it turns out, is no more protected from the relentless assault of air pollution than is any other organ.”

Also, FPM enters into the bloodstream via the lungs, which this mutation might also make more permeable. Still, I am cheered by this remarkable find. Who would have thought that humble mucus might be part of the story?

P.S. to Cort. Unusually, the American-speaking world appears to agree with the English-speaking world, for a change, in agreeing that “mucus” is the noun and “mucous” is the adjective (“mucosal” being an alternative, adjectival form).

Correction: “mucosal” pertains to the mucous membrane; and “mucous” pertains to mucus itself.

Thanks. I was totally guessing on mucus. I knew there were variations but had no idea the right one. Thanks for clearing that up. 🙂

wonder if the nose route to brain explains loss of smell for some covid and alzeimer disease patients. perhaps the route of entry explains the range of symptoms seen—nose versus gut versus thru eyes versus ears or skin.

route might inform cfs/me one day

Bless you Cort, I do not remember a time that my face has not constantly hurt with a headache. I have POTS also, I’ve not heard of autonomic rhinitis, what type Dr would dx that? I have my raw DNA data. I’ had CFS, Fibro for 30 years. I am not living, just barely existing. I’ve had extensive blood testing and it was a toxic soup. I’ve had chelation, vitamin infusions…thru the years, on and off, limited resources to continue. Mast Cell and POTs on DNA reading from Genetic Life Hacks. MCS, I can’t process smells,or Lectins; which also crosses the blood/brain area. Keep up the good work everyone. We can surely figure this out, if not for us, our children.

Would this explain MCAS when exposed to chemical odors?

Interesting and wholly unexpected finding. This sounds like making sense. Thanks for the good write up Cort!

Thanks!

Hmm, when one reaches the stage of ME one has a high chance to have combined low blood volumes, inflexible RBC and a fight-or-flight reaction.

All three should reduce blood flow in near all epithelial layers like skin and gut, and they should reduce blood flow there more then in the rest of the body.

So, once the stage of ME is reached, these epithelial layers likely has considerably less access to decent blood flow while needing more energy to repair and defend against invading pathogens. That very likely should leave fewer energy and materials to build mucus from. If that isn’t a “nice” vicious circle we have at hand here.

Now with both a strong infection or long term exhaustion one should have enough oxidative stress to make RBC less flexible, triggering at least one part of this nefarious vicious circle.

Also, strong inflammation is known to increase viscosity, hampering blood flow through the many fine capillaries of the epithelial layers. That could also contribute to the vicious circle.

Strong infection able to provoke a sepsis can also cause the well known septic shock giving a severe and dangerous drop in blood pressure. That again would decrease the blood flow in epithelial layers more then in the rest of the body. Even if it only happened in part, it again could contribute to the vicious circle.

dejurgen, would that thickening of bloodflow be why some used hepatin to treat me/cfs in past

“Dr. Holtorf is still putting Berg’s findings into practice. At the recent LDN conference, he called heparin one of his favorite treatments for ME/CFS/FM.”

https://www.healthrising.org/blog/2015/04/01/big-studies-big-possibilities-montoya-and-unger-on-their-chronic-fatigue-syndrome-programs/

It now seems as if

whatever was ‘old’

in cfs/me

is coming up ’new’

………for covid:

“COVID-19 Drugs: New Research Indicates That Heparin May Effectively Neutralize SARS-CoV-2 Coronavirus That Causes COVID-19”

https://www.thailandmedical.news/articles/news

Some of us have found issues with too thick blood. Either with APS or with me Factor 8 and Collagen Binding. There are other ways to thin the blood other than heparin. I’m using enzymes and herbs. It does seem to make a difference.

Blood volume issues also a problem with POTS. So that too plays a huge part with me.

I have no experience with heparin.

I however strongly believe that improving blood flow, as in blood flow being better able to adapt to needs rather then plain increasing it, is an important element in ME.

The difficult part is that blood gets more viscous or thicker the slower it flows. So part of this thickening comes from reduced blood volumes, inflexible RBC and constricted blood vessels.

So IMO thinning, by using heparin or other drugs, might help but will be largely unable to help blood flow optimally adapt to varying needs.

I would like to see studies on the effect of blood thinning on the blood flow in the finest capillaries first to better know if and how this would work for them as I believe there lies the biggest trouble for ME blood flow.

Has the study been published in a journal? Looking for a link have yet to find one.

No studies published yet.

Wow this is me! Thank you so much for this information. It totally explains and validates the midfacial pain behind my nose. My doctor here in Los Angeles had told me that viruses enter the nose and can travel via the olfactory nerve to the brain. I’ve had several CT brain scans, CT sinus scans, and they even inserted a probe up my nose to look at my sinuses. They always tell me everything looks normal. But I’ve had this pain and problems for 5 years. Now I don’t have to feel like the neurologist who told me it was nerves and would go away is right. So thank you so much again. It all makes perfect sense to me!!! I hope this is a stepping stone for some answers.

Has anyone ever looked at a history of nose bleeds in ME/CFS? When I was in my teens I ended up having to have my nose cauterized to stope excessive nose bleeds (frequency, primarily). I can’t remember the exact timing but this was around when I was wiped out for six months with EBV/mono. It is quite an experience to smell you own burning flesh at such close proximity! I haven’t had any nose bleeds issues since though.

Not sure how I feel about this one but it’s interesting. I’ve had bad allergies throughout my life and am also a cystic fibrosis carrier. (I have ME/CFS).

Article published on SinusitisWellness.com as a tribute to Dr. Jack Thrasher and his most recent paper with Dr. Dennis, “Surgical and Medical Management of Sinus Mucosal and Systemic Mycotoxicosis.” The synopsis and explanation is excellent on SinusitisWellness.com

This led Dr. Thrasher to his extensive work investigating, “Water-Damaged Building Syndrome.” He and his partner, Sandra Crawley, actually published a well-known and highly-regarded paper, entitled, The biocontaminants and complexity of damp indoor spaces: more than what meets the eyes. Very basically, the paper presents their findings of indicator molds; Gram negative and positive bacteria; microbial particulates; mycotoxins; volatile organic compounds, both microbial (MVOCs) and non-microbial (VOCs); proteins; galactomannans; 1-3-β-D-glucans (glucans); and ipopolysaccharides (LPS — endotoxins) in high concentrations throughout water-damaged indoor environments. The paper discusses the dire health implications of all of these particulates in a building or indoor environment, where humans are working or reside. He shows how the bacteria and molds are equally infectious and work together to cause significant and sometimes deadly (cancer) health problems. Thrasher would go on to point out the existence of protozoa also present in these wet indoor spaces, capable of causing infestation and infection—which was never indicated or tested before this paper.

Dr. Thrasher wholeheartedly believed that excessive mold was more dangerous to the human body than heavy metals or pesticides, simply because his work and testing had shown him that mold could adapt and mutate. Mycotoxic molds would affect human biology from a person’s head to their toes, interfering with protein synthesis, and suppressing the immune system, so that humans can never become resistant to them. His paper with Dr. Dennis highlighted the impact that mycotoxins can have in the sinuses and the complex diagnosis and treatment required for patients to get well.

https://moldfreeliving.com/2017/06/03/dr-jack-thrasher-a-toxicology-pioneer-and-mold-warrior/

PLAY ALL

Toxicology Expert Dr. Jack Thrasher on Mold Exposure

6 videos7,014 viewsLast updated on Aug 22, 2013

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PL08AA426681517CFC

Toxins (Basel)

. 2013 Apr 11;5(4):605-17. doi: 10.3390/toxins5040605.

Detection of mycotoxins in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome

Joseph H Brewer 1, Jack D Thrasher, David C Straus, Roberta A Madison, Dennis Hooper

Affiliations expand

PMID: 23580077 PMCID: PMC3705282 DOI: 10.3390/toxins5040605

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23580077/

Thank you Cort Johnson for your faithfulness over all these years. I just had my DNA done through dna consultants and found out that there is a good chance I may have genes that carry familial Mediterranean fever. Having looked up what that is I find it significantly close to all of my fibromyalgia symptoms that I have had since I was a child and watched my parents with similar symptoms to a degree and 6 brothers and 1 sister with varying degrees of different symptoms. I am 65 now and have prayed for years for the people with this disease. I thank you and if this information helps you at all thank the Lord.

Very interesting. I am homozygous (2 copies ) for the MTHFR C677T. Most doctors say it is nothing. I too have the chronic mucus. It became so thick, I could not release it. I also have long term mold exposure. When I vacated apartment for two plus years to have repairs done my health returned. Since my return I have become ill again with all the ME?CFS symptoms. Immunologist wants me to start IVIG therapy of 7 grams per week.

Time for a new abode! Not easy I know. I camped for years half the week.

This might be a part of the puzzle as to why corticosteroids can make us worse: they can thin the skin and they can banish much of the mucous layer.

Hi I just wanted to share that I get these very painful sinus type of problems. My sinuses and behind my sinuses in my head get in a state that are so painful I must lay down and not move for days at a time. I do not get an infection with any mucous built up. Instead, the pain is so unbearable it feels as if someone is taking a surgical knife and scrapping my sinuses raw without any anesthesia with these strange type of migraine head pain. This happens often and comes in a cycle a last for 2 days and the third day the pain starts to subside. Then my sinuses feel tight, and they are crusty inside with blood. I have no mucus discharge. I have been to a sinus specialist, and they said everything looked good and had no explanation. They did want to preform and MRI of my sinuses which I have not done yet due to the cost.

I also forgot to add that I have tested positive for the MTHFR gene.

I keep adding to my initial remarks I believe today it is from my cognitive disfunction. I have also been diagnosed with Sjogren’s Syndrome and get the dry eyes, mouth and all the other symptoms from Sjogren’s Syndrome. I also have been diagnosed with gastrointestinal problems. I have been too sick to go to the specialist to see if it is IBS or Chron’s disease or what the problem is, but it is bad I have lost about 10-15 lbs. and so much muscle tone. I lost my appetite and can only eat certain foods, or I get extremely nauseated I defiantly have chemical sensitivities. We remolded our house and backyard and moved a lot of dirt plus all the floors and drywall and things from remodeling put me in a verry bad place. I live in California, and we also were having horrible wildfires that affected the air quality. After that I became extremely ill and have been mostly bedbound or homebound since and that was about 8 years ago. for almost 5 years i could barely lift my head and was in bed all the time in terrible pain. I was also involved in an automobile accident in 2015 where a drunk driver hit my husband and I and we both had Traumatic Brain Injuries with post concussive syndrome. After all of that I am now very ill. Before I had been diagnosed with ME/CFS 33 years ago and at one point after being on years of 3 different antibiotics and getting off all medication I had gone into a type of remission for about 8 years and was working full time. I still had many symptoms but was able to do life. Now I am very sick everyday with so many symptoms. I am slowly getting better and can get out of bed and do short walks. I can sit up in bed. I still have a very hard time with showering and just the basic self-care. My cognitive function and brain fog are very bad. I do spend most of my day in bed. I am hoping to get back into life where I can work and feeling better again. I have tremendous sleep problems and the exhaustion feels like I could die at any moment. It is painful exhaustion. I describe it as if you were living in a concentration camp and not being feed properly, tortured, not getting enough sleep and made to work yourself to the point of near death. I do not feel human. I feel as if I am just trying to survive moment by moment. I feel we need to take this ME/CFS very seriously and find the cause and treatments. I thank all of you who work so hard to help anyone suffering with these diseases. Gulf War Syndrome, Mast Cell Activation, ME/CFS, Fibromyalgia all the diseases you are trying to help find the cause and cure. Thank you so very much it means so much to me that you care and are trying so hard to help so many sick people. Thank you from my heart.