This is part three in a multi-part sleep series on fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) dedicated to Darden Burns.

Health Rising’s ME/CFS and FM Sleep Series

- Sleep Pt. I: Why We Sleep (and What Happens When We Don’t)

- Why We Sleep Pt II: Walker on the Dark Side of Sleeping Pills and a CBT That Works?

- The Sleep Issues in Fibromyalgia: an Overview

________________________________________________________________________________

O sleep! O gentle sleep! Nature’s soft nurse, how have I frighted thee, William Shakespeare

Sleep. If only one could get more of it or better of it, how much of fibromyalgia (FM) or chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) would simply disappear? Good sleep is so rare in these diseases that Dr. Eleanor Stein starts off the sleep section in her online ME/CFS/FM course by reminding her patients what a good night’s sleep actually looks like.

Nobody knows the effects poor sleep has on FM in part because no ones been able to consistently get people with FM to get really good, deep sleep. There are certainly ways to improve sleep, but consistently getting really deep, healthy sleep is just beyond most of us.

That’s unfortunate, as the costs of poor sleep are many. Sleep, it turns out, is not the absence of activity. Some parts of the brain are actually more active during sleep. Memories get encoded; cognitive connections get established; in a very real sense, learning takes place; toxins and sewage get pumped out; immune enhancement occurs; hormonal changes happen.

Getting poor sleep on the other hand, actually activates the fear center of the brain (the amygdala) – leaving us edgy and emotionally reactive. Lactic acid piles up, aerobic energy production declines, blood oxygen levels drop, sympathetic nervous system activity (fight/flight) spikes, your ability to fight off pathogens decreases, inflammation soars, the rates of atherosclerosis and heart attack increase. It’s not surprising, given all that, that consistently poor sleep is associated with increased mortality.

Pain, Fibromyalgia and Sleep

It makes intuitive sense that being in pain would impact one’s ability to sleep – and that’s what the studies have found. Being in pain makes it hard to relax enough (pain increases the fight/flight response) to get to sleep and to stay asleep. Poor sleep is often found in chronic pain conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, cancer pain and headaches.

It actually goes both ways. Getting poor sleep is also a really good way to notch up your pain levels. Numerous studies have shown that depriving healthy people of sleep increases their pain sensitivity. Totally depriving a person of sleep over 24 hours results in the same kind of pain hypersensitivity found in fibromyalgia.

Temporal summation or “windup” – the process by which the nervous system gets put into a hypersensitive state – gets wound up. Controlled pain modulation – the process by which pain signals get ameliorated – gets impaired. Both these problems are found in FM.

A 2018 study that followed two cohorts of patients over five and 15 years found sleep problems (such as trouble getting to sleep, waking up in the middle of night, reduced sleep times, non-restorative sleep) approximately doubled one’s chance of coming down with chronic widespread pain. (Interestingly, fatigue also dramatically increased one’s risk of coming down with widespread pain.)

If you were getting poor sleep prior to coming down with fibromyalgia, it’s possible that poor sleep increased the risk of getting it. Adding the pain of FM to the equation probably made your sleep worse. A combination of poor sleep and pain may have increased your risk for yet another common problem in FM – depression.

How much easier it would all be if we could all just get better sleep. The list of sleep problems that studies have found in FM is not a short one.

The Sleep Disturbances in Fibromyalgia

The feeling of waking up unrefreshed (or even feeling worse than when one went to bed) is very common in both FM and ME/CFS. So is daytime sleepiness and the need to take naps. These are mostly subjective, but still telling, measures. Both indicate there’s a real problem with sleep in FM.

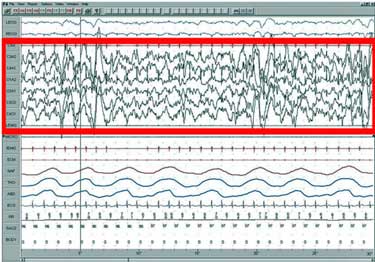

One possible cause that has been looked at concerns the spikes of high frequency alpha brain waves that pop FM patients out of slow wave sleep. This is an intriguing possibility as it could provide a finding that was more or less unique to FM and ME/CFS. Questions regarding alpha brain waves in fibromyalgia and ME/CFS date back an astounding 45 years.

Follow-up studies, however, had mixed results over time. A 2000 review cast doubt on the alpha finding and concluded that while sleep problems were present in FM, it was not a sleep disorder per se. A recent meta-analysis of 25 FM sleep studies did not – to the author’s surprise – find evidence of increased alpha brain wave activity in FM. Nor did it find the significant increase in arousals during slow wave sleep that alpha intrusions would produce.

The analysis did find, however, a reduction in slow wave sleep – which has been associated with unrefreshing sleep, widespread pain, tenderness and fatigue, as well as reduced sleep efficiency, longer wake time after sleep onset, shorter sleep times, and light sleep. While a smaller recent study did not find alterations in total sleep time, time to go to sleep, time awake after going to sleep, or levels of alpha-delta sleep, a quite large 2016 study (n=132 FM patients) found decreased sleep times and slow wave sleep (SWS), more difficulty going into deep sleep and wake times during sleep. Those findings seem set.

With its long, slow, perfectly synchronized waves, Walker characterizes slow wave sleep as a “nocturnal cerebral meditation” or long, slow swells rippling across a placid ocean surface. Emanating from the middle of our frontal lobes (about the middle of our forehead), the swells transfer data from our short-term to our long-term memory stores in the neocortex. This type of sleep occurs during the early night-time and is a good reason not to stay up too late. Your ability to remember something from the past day and learn from it is a function of early night, deep slow wave or NREM sleep.

Other study results have not been validated. One study, for instance, found reduced spindle activity. Spindles help tranquilize the brain – allowing it to achieve restful but productive sleep without interference from the outside. By integrating short-term memories gathered during the day into long-term databases in the brain, they also facilitate learning.

in contrast to slow wave or NREM sleep, spindle activity occurs in the late morning. If you’re consistently waking up early you might miss some of it. With just one 16-year-old FM spindle study, though, we can’t say that spindle activity is impaired in FM.

Ironically, given its prevalence in the population, only one small 2013 study (n=40) has assessed the prevalence of sleep apnea in FM as well. (Another older study found a high occurrence of periodic breathing – which may be similar to sleep apnea.) Dr. Klimas has reported finding a high incidence of sleep apnea in her ME/CFS/FM patients. The 2013 study found that over 60% of male FM patients had a high “apnea-hypopnea index” and 32% of women did. (Males also had poorer sleep quality and slow wave sleep). While no one thinks sleep apnea is the cause of FM, a couple of studies on sleep apnea would be very helpful clinically.

It may be that sleep researchers are so focused on finding the cause of fibromyalgia they haven’t looked at comorbidities such as sleep apnea, which we know aren’t causing it, but which could be making the symptoms of fibromyalgia worse.

While studies have found numerous problems with sleep in FM, nothing yet indicates any unique problems not found in other diseases are present. Instead the sleep issues may be be part and parcel of having a disease characterized by chronic pain.

The Gist

- Poor sleep has been found to increase the risk of coming down with a widespread pain disorder such as fibromyalgia.

- Poor sleep also increases pain sensitivity, causes cognitive problems, disrupts the autonomic nervous system, dysregulates the immune system, impacts the cardiovascular system and on and on.

- Studies indicate that people with FM typically experience reduced amounts of slow wave sleep, reduced sleep overall, take longer to get into deep sleep and have reduced sleep efficiency.

- People with FM do not, however, appear to have increased intrusions of alpha brain waves. It does not appear that the sleep problems found in FM are unique to the disease. Instead people with FM appear to have an amalgam of sleep problems similar to those experienced by others in chronic pain.

- Poorer sleep is clearly associated with increased pain in FM: the worse sleep you have the more likely you are going to be in more pain.

- Only one sleep apnea FM study has been done but it suggested that high rates of sleep apnea may be present – particularly in men.

- Recent studies suggest that activation of the fight/flight (sympathetic nervous system (SNS)) in FM is implicated in the sleep problems. One paper suggested a vicious circle had occurred: chronic pain jacks up the SNS, which impairs sleep, which then causes more pain sensitization.

- From problems with the opioid system to neurotransmitters (serotonin, norepinephrine, dopamine) to orexin to nitric oxide, to immune problems, etc. many other systems may be affecting sleep in FM.

- Neuroinflammation could potentially be at the root of the sleep problems in FM. Given the amount of work focused at batting neuroinflammation down in other diseases that might be a very good outcome…

The Sleep-Pain Connection

The connection between poor sleep and pain is clearer. A systematic review of FM sleep studies that examined whether sleep problems were increasing pain in FM and assessed study quality found, as expected, some holes. Only one study, for example, objectively assessed sleep duration. All the studies found that people with FM were sleeping less than normal. One found reduced sleep times were associated with increased pain levels, while another did not.

The results were more consistent with sleep quality. All 9 of the studies measuring sleep quality concluded that worsened sleep quality was associated with increased pain levels in FM. The few studies which measured “sleep efficiency” – the amount of time spent trying to sleep vs time spent actually sleeping – found that reduced sleep efficiency was associated with more pain as well.

Overall, nine of ten studies found that poorer sleep was associated with more pain in FM. Several studies also found, not surprisingly, that poorer mood was associated with poorer sleep. That brings up the question whether the depression found in some people with FM might be more a function of their not being able to get a good night’s sleep.

The Cause of the Sleep Issues in Fibromyalgia

Given that sleep issues have been identified in FM and other chronic pain conditions, the next step is identifying the biological cause. A recent review, “Sleep deficiency and chronic pain: potential underlying mechanisms and clinical implications“, provides a good, but rather disconcerting, overview of the many possibilities present.

The senior author of the paper, Janet Mullington, interestingly enough, applied for an NIH ME/CFS research center. Way back in 2001 she authored a paper suggesting that cytokines and inflammation may be disrupting sleep in ME/CFS.

Autonomic Nervous System

Mullington has been on the cutting edge of understanding the role the autonomic nervous system plays during sleep – an intriguing subject for people with ME/CFS. Darden Burn’s dramatic arousals shortly after going to sleep may have resulted from poor ANS control. Just last year, Mullington co-authored a study which showed that restricting the sleep of healthy volunteers resulted in reduced heart rate variability – a common finding in both FM and ME/CFS.

Reduced sleep results in increased blood pressure during sleep. Other autonomic nervous system factors may play a role as well.

In 2017, she showed that chronically reduced sleep durations in healthy people was associated with reduced “blood pressure dipping”. Our blood pressure usually declines by 10-20% as we enter into slow wave sleep, but when Mullington restricted sleep in healthy people, she found that their blood pressure tended to remain high – and likely impaired their sleep further. Plus, she speculated that increased sympathetic nervous system activity may have resulted in blood vessel vasoconstriction or narrowing – thereby providing a new way to possibly explain the low blood flows in ME/CFS. Interestingly, sodium excretion – a possible factor in the low blood volume found in ME/CFS – also increased – which brought up the renin-aldosterone-angiotensin which we know is impaired in ME/CFS and POTS. All told, Mullington was able to potentially link a rather remarkable array of factors in ME/CFS to poor sleep.

Several studies have linked autonomic nervous system dysfunction to poor sleep in FM. One suggested that simply being in pain was creating a vicious circle of increased flight/flight or sympathetic nervous system activity, poor sleep and more pain.

“A vicious circle is created during sleep: pain increases sympathetic cardiovascular activation and reduces sleep efficiency, thus causing lighter sleep, a higher CAP rate, more arousals, a higher PLMI, and increasing the occurrence of PB, which gives rise to abnormal cardiovascular neural control and exaggerated pain sensitivity.”

Other Possibilities

Mullington listed a rather daunting list of other factors could be whacking sleep – several of which are certainly options for FM. Since the opioid system affects both pain and sleep, problems with that system, such as decreased opioid receptor availability, have been proposed. That’s an interesting idea given a study which found just that problem in FM. Since the serotonergic system regulates both pain and sleep/wake control, a pumped up serotonergic system (see Cortene) is a possibility. Norepinephrine and dopamine are two other duo sleep/pain neurotransmitters – both of which have been possibly implicated in FM and ME/CFS.

Nitrogen oxide, the orexin system, the paraventricular nucleus in the HPA axis, the immune and endocannabinoid systems and others could play a role. Problems with each may be found in FM and ME/CFS.

While disentangling the sleep issues in FM may not be easy, it’s possible one central actor – inflammation – could be behind all of these problems. Mackay proposed that inflammation was dysregulation the paraventricular nucleus – an important sleep/wake center in the hypothalamus.

Mulligan pointed to some recent data suggesting that reducing inflammation with biologic drugs may be helpful with sleep. Plus, prominent FM researcher Daniel Clauw also recently proposed targeting the glial cells that produce inflammation in the brain to improve sleep in diseases like FM, which are characterized by central sensitization (i.e. central nervous system caused pain and sensory hypersensitivity).

If, in the end, it all came down to combating central nervous system inflammation, that could be very good news indeed – as funding into that issue has been ramping up in other diseases. One hopes for real movement in that area in upcoming years.

This is part three in a multi-part sleep series on fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) dedicated to Darden Burns.

Health Rising’s ME/CFS and FM Sleep Series

- Sleep Pt. I: Why We Sleep (and What Happens When We Don’t)

- Why We Sleep Pt II: Walker on the Dark Side of Sleeping Pills and a CBT That Works?

- The Sleep Issues in Fibromyalgia: an Overview

Coming up – projected

- The Sleep issues in ME/CFS

- Treating Sleep – What do the studies say?

- Outside the lab – Other Treatment Options

- The Future Sleep Drugs

With the information from the recent blog on the energy problems encountered in Pettersen’s studies –

“… the energy production picture in ME/CFS was akin to what is seen during starvation: glucose utilization drops, ketone bodies soar and fatty acid levels rise.” – and the ensuing discussion in the comments of that post as a backdrop:

Given that different stages of sleep require different levels of energy – with REM requiring as much or more as during waking state – we can begin to appreciate why sleep is not restorative in ME/CFS, and quite the opposite: byproducts and substances can build up to higher than normal levels during sleep – and it can take all day to ‘clean up’… that feeling that a truck run as over, as if hangover. That stiffness and pain when first getting out of bed that ameliorates after some time moving about (lactate?)

Indeed –

it takes me about 8 hours to ‘wake up’ once I am no longer sleeping, the moving through molasses in body and mind, the lethargy. This has been a defining trait since I’ve been a kid, loooong before ME/CFS and PEM entered my clinical picture or vocabulary.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

If during the day we can feed as needed to compensate and serve as alternate energy sources – bed time is basically 8 hours (more or less) of fasting.

Could it be that something about how our cells meet energy demands at night is different from how they do in the daytime? I wake up with a terrible smell permeating my room. It doesn’t happen as much during the day (only when I had more pronounced illness severity). Ammonia emanates from my skin in daylight only – a marker of catabolism as I’m gathering from the studies on NH3 from Armstrong’s team in Australia. Could it be at night metabolism switches to a catabolic state, and ammonia builds up in the course of night, to be cleaned out over the course of the day? We also don’t get to excrete toxins through urine for 8 hours more or less while we are sleeping.

Take the issues we experience during the day with orthostatic intolerance, blood viscosity and flow: at night, we are in one position, supine, for 8 hours (more or less). What mechanism do our bodies deploy to get blood to where it needs to during our sleep? A common experience is of waking up in the middle of the night, drenched in sweat, heart racing – a POTS attack? Nor-epinephrine? I used to be jolted by an asthma attack right as I was falling asleep, or woken up by fits – histamine? And then when I did finally wake up – my nose would get stuffed as if it had forgotten to do so while I was sleeping. Or waking up in the middle of the night to a mind that is teeming with thoughts as if it would have never stopped (low GABA?). And what about those experiencing vivid, lucid dreams?

How do neurotransmitters and hormones intertwine with energy production in sleep?

+ Serotonin is converted to melatonin by action of acetyl-coA and the methyl group in SAMe.

Disrupted serotonin production can theoretically drive SAMe down – acetyl-coA?

Disrupted 1-carbon cycle can affect SAMe, which leads to less methyl available to produce melatonin.

+ Serotonin is synthesized from tryptophan – may the (for now hypothetical) metabolic IDO trap be affecting serotonin production as well?

+ Melatonin also has a role in muscles:

“https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32157560/“

There are other neurotransmitters at play during sleep.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

This is an interesting paper:

“The energy allocation function of sleep: A unifying theory of sleep, torpor, and continuous wakefulness”

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0149763414001997

Here you can read of subjects Cort has been covering and we have been discussing in the comment section of blogs lately. Ion channels (potassium, calcium, magnesium), energy production, neurotransmitters, muscles, fluid balance (intra and extracellularly):

“Brain Energetics During the Sleep-Wake Cycle”

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5732842/

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

My guess is FMS has a similar metabolic problem? It will be interesting when they get around to doing metabolomics in FMS too.

Or is there another way to look at this? Something that is going on during the day affects our nights?

Really interesting Meirav. You are so right – I looked it up and our brains do appear to clean themselves using the glymphatic system during sleep.

“Nedergaard and her team found that the glymphatic system was most busy as the animals slept. They showed that the volume of interstitial space increased by 60% while the mice were sleeping.

This volume increase also boosted the exchange of CSF and interstitial fluid, speeding up the removal of amyloid. They concluded that:

“The restorative function of sleep may be a consequence of the enhanced removal of potentially neurotoxic waste products that accumulate in the awake [CNS].”

Letting toxins accumulate would be a great way to explain the getting hit with a bat feeling that sometimes comes upon awakening.

..https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/325493#The-importance-of-sleep

Thanks for the links!

A system in the brain analogous to the lymphatic one – how interesting!

And blood flow influences it’s functioning, hence blood pressure/heart rate too. And it modulates cerebrospinal fluid movement.

Makes you wonder about the relationship to cranial hyper/hypotension that we often talk about in POTS and orthostatic intolerance.

The bit about how it “connects with the lymphatic system of the rest of the body at the dura, a thick membrane of connective tissue that covers the CNS.”

The closest lymph nodes are cervical ones, as you can see in this image:

https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Drainage-of-CSF-via-the-meningeal-lymphatic-system-A-Part-of-the-CSF-drains-from-the_fig1_337726815

– makes me wonder how wonky connective tissue, craniocervical instability and positional cord compression (seen in FMS) influence this system too.

http://www.positionalcordcompression.com/images/PacificRheumAssoc_PC3_2012.pdf

And then how it connects to the rest of the body.

https://www.jimmunol.org/content/204/2/286/tab-figures-data

Cytokines are involved as well.

How cool all this new information is – maybe a different perspective on our problems.

Neuroinflammation may be a result of a built-up pf byproducts and substances. Same in the other conditions mentioned in the article – Alzhemeir, Parkinson’s. Maybe in autism. Who knows what else?

Perhaps it originates with a metabolic disorder. From there, the rest follows.

More and more, I am reminded of Naviaux model of dysfunction.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

Ah, glial cells – which the glymphatic system is named after – I recall from the research literature on PEA (palmitoylethanolamide). It is used for neuropathic pain in FMS and hEDS successfully by some – I being one of them. One does need to let it build up overtime – they say two months. And then you can titrate down, may not need it again, or leave it at the same dose, as needed, etc.

Ah, by the way – my histamine surges correlate with changes in ATP production when transitioning from waking to sleeping, and vice-versa, per the paper on the second link I posted before.

– – – – – – – – –

Here is a newer paper from Markus Schmidt:

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/320318602_State-dependent_metabolic_partitioning_and_energy_conservation_A_theoretical_framework_for_understanding_the_function_of_sleep

I like how the model he proposes does not place sleep/wakefulness in a binary relationship.

We can frame the sleep problem in ME/CFS and FMS (and hEDS?)

as a continuum of the energy production/utilization problem.

Now it’s time for bed! Good night I say.

When you can’t sleep, you can at least read about it! (It’s well after midnight here, and after a migraine-day with a soothing cranio-sacral session, my body and brain have clearly decided that’s more than enough rest and I shouldn’t be so greedy!)

Thanks for this, and all the links.

Walker’s book was fascinating and great for information, (and falling asleep to — the audiobook narrator was well chosen), but rather low on effective solutions – for our crowd at least I can’t speak for those fortunate unfortunates who merely have regular sleep difficulties.

Maybe I’m not reading the right research, but the common trend seems to be loads of studies into what’s going on and very few answers into what we can do to alleviate it. (That really work for us and don’t just make us feel that we’re “dirty” sleepers because our sleep hygiene is poor.)

Maybe I’m just too impatient to get a life back… while at the same time I’ve never sensed that this is going to be a long term thing for me. (It’s only just shy of a decade so far, that’s short-hauler isn’t it? ?)

I’m curious to know what the biologic drugs may be, when “Mulligan pointed to some recent data suggesting that reducing inflammation with biologic drugs may be helpful with sleep.”

There are a few studies that can provide some hope – but no magic bullets that I can tell yet. I believe one biologic drug was a TNF-a blocker – which Klimas is trying in GWI and ME/CFS. 🙂

I’ve been watching the Parasympathetic Summit – Stephen Porges, Titus Chiu, Niki Gratrix, Alex Howard and also Dr Datis Kharrazian on the Bio-Optimise Summit and for me they’re circling around areas that are totally relevant to me – a chronically elevated sympathetic nervous system, brain inflammation, emotional trauma – they’re all something I live with. I am becoming more familiar with their effect on me and I’m getting better at handling them.

Even though I juggle these issues on a daily basis I’m really doing well. This week I actually felt normal. However I was searching in my memory for something to compare my current experience with. My life has changed so much it’s difficult to gauge but I feel so many of the pieces of my jigsaw are finding their place. Now I’m thinking – for years no one believed I was so unwell and now they’re ‘proved’ correct, as I’m now so much better!

I was just thinking to myself – yeah it’s understanding the nervous system and somehow tapping into the parasympathetic nervous system and getting better sleep that can make such a massive difference – as I picked up my phone to go to bed. I saw there were 2 messages and decided I’d have a quick look and had to laugh when I saw the Health Rising topic 🙂 Now it’s really late!!

I don’t have FM and I’m not in pain and so that makes things easier for me. I’ve spent most of my adult life engaged in therapy/personal development because I needed it. I spent years training as a therapist, so I understand the concepts. However none of that was much help when I was barely able to think and couldn’t remember anything.

We all come from different backgrounds and have different issues and everyone needs to start from where they are. I believe my sympathetic nervous system was revved up before I was born and then the rest of my life occurred! Having said that I think I’ve learned a lot and I honestly believe I’m finding my way out – I have more energy, I can think and I’m starting to live a bit, instead of just trying to survive 🙂

I have been thinking how fortunate I am that I’ve found things that have helped me regain so much functional ability – I’m not free of potential issues – I’m just better at possibly circumnavigating them and keeping them at bay. And in particular I have been thinking of Darden Burns and others like her.

We desperately need to understand what is going on for people because being ‘lucky’ (like me) isn’t good enough. These issues are very complex because we, as humans, are very complex.

I think that the misinformation and skewed thinking surrounding ME/CFS has done a great disservice to individual suffering. I see from #MEAction that NICE are about to release their revised guidelines on ME/CFS in the UK. It’ll be interesting to see what they’ve come up with…

I’ve just seen now that, according to #MEAction, NICE (UK) have dropped Graded Exercise Therapy (GET) from their draft guidelines for ME/CFS. So that’s a start.

Yes, Darden was so interesting. She did meditative work for years and it did calm her SNS down – but ultimately it was not enough for her. Her SNS appeared to be on full time….

Coming from the EDS camp, where fatigue and fibromyalgia-like symptoms are prominent, one of our EDS gurus, Dr. Pocinki, has done a lot of looking at sleep. One thing he has noticed is that most sleep doctors don’t know how to interpret ‘micro’ awakenings and instead mostly focus on things like apnea. He speculates that those micro awakenings are caused by autonomic dysfunction–especially POTS and hyper-POTS.

Speaking of apnea, for those of us with EDS, UAR (Upper Airway Resistance caused by ‘floppy tissue’) is a common yet under diagnosed cause of sleep deficiency. It requires a special, somewhat uncomfortable test, to diagnose.

For myself, my problems are mostly from joint and especially spinal pain, choking on saliva from achalasia, menopausal hot flashes–and the need to pee after taking a lot of meds in the late evening. When describing these issues to explain my hypersomnia (fatigue and falling asleep during the day), I was partially dismissed as the doctor said it was ‘common’ for older people not to have extended deep sleep.

Common doesn’t mean healthy. I’m still in search of additional ways to improve sleep. I manipulate my a.m. energy with modafinil and find that attempting to go to bed earlier (if I can avoid that late night surge) helpful. As Cort mentioned in one of his threads, if good hygiene doesn’t work, sometimes cannabis does…

As a ‘patient’ being categorised in some sort of statistical fashion isn’t very useful Nancy, is it? When, after possibly years of suffering near constant undiagnosed asthma attacks, my doctor said to me that it was very rare, (1%) or so of people, to have asthma without wheezing (ie it affected my lower airways) I just looked at him dumb founded. For me individually it was a huge problem, whether I was statistically rare or not. Just because it may be ‘common’ for a section of the population to have sleep issues doesn’t make it okay!

@Tracey, I couldn’t agree more–especially since EDS is still considered ‘rare’ as well–never mind other categories of people–like ‘older’ or with ‘asthma.’ I think that medical saying, ‘When you hear hoofbeats, think horses, not zebras’ may need some revision–especially in more challenging/resistant medical conditions. Too often it can cause diagnostic blindness.

I don’t know about you, but a new doctor ‘taking a detailed history’ has just about disappeared in my experience. This last time, before my appointment, I sent over a ‘patient summary’ describing the history of my complaint, pertinent facts, and current concerns.

The doctor was so surprised to get it and said over and over again how helpful it was. You would think that a doctor could read past notes and ‘know’ a patient–but often that isn’t so. Unfortunately, with some of our complaints, even though you can send all your history, it doesn’t necessarily mean there is much treatment available.

Sorry about my prattling on, but it triggered the frustration in dealing with these issues.

The ‘diagnostic blindness’ is so true. My current GP is a nice person but what I see in his eyes and demeanor if I start talking about the weirder symptoms – and I’ve had a stack of them over the years – is a disbelief and confirmation that I’m overly anxious and too invested in being unwell. I find that immensely unhelpful and insulting. It’s been very dangerous too – as I really did have an inflamed brain but he didn’t believe me.

I sometimes feel I’d love to become a hermit and live somewhere out in the wild and not have to talk to anyone anymore!

Anyway that’s not going to happen but now that I’m feeling so much better and can pass off as a normal person, I’m not sure what I can usefully do with the bottled up feelings of frustration from years of being dismissed and misunderstood… I’ll have to have a think with my reclaimed brain. Wishing you the best Nancy 🙂

An interesting sleep-related observation re positive effects of LND for my teen son. His usual response to over-exertion is unable to sleep all night and most of next day (not a wink, Hyper-awake, hyper vigilant). He doesn’t take naps as I read some ppl do. The less sleep, the more wired he gets. (Although sometimes will bank up massive sleeps, like 16hrs). So, LDN actually made him more sleepy/exhausted for the first few weeks (or did his body just respond more normally to it?). He was taking himself off to bed before midnight each night, unable to keep his eyes open (Very rare). At first, we thought this was a bad thing. But it gradually became clear the quality of his sleep was improving. That sense of worse exhaustion (Ie. more overwhelming than his baseline) receded after first few weeks. Four months on, episodes of PEM less common, & less severe. He wakes up more fully/quickly, is less brain fogged and is hungry immediately (MIA for years). No other changes to his meds or long-established routine (5 yrs mostly housebound). Hope it lasts.

That’s so interesting Shelley. What I’ve found over years is that I often don’t actually know exactly why something is helpful or unhelpful, I just know that’s what’s happening!

Thanks for sharing this Shelly. I’ve been nervous to try LDN because of hectic paradoxical reactions and side effects from just about all pharmaceuticals (and cannabis).

I was very interested/relieved/intrigued to read about your son’s symptoms. I have the same contradictory experience of being more wired and less able to sleep the more exhausted I am. (Minus the long “banking” sleeps, sadly my body’s max is 7 hours, if I’m lucky.) I’ve described it as being like an overtired child who is clearly exhausted and still insists on playing and has a temper tantrum about going to bed. (Fortunately my sense of humor is somehow immune to sleep deprivation!)

Also interested to note his MIA hunger in the mornings, which I haven’t heard from anyone else before — Miss Absolutely Loves Food here has been wondering whether there’s some starvation-type response going on in me because I’ll usually only want to eat 4-6 hours after waking, making it a good 14-16 hours since last eating. My consolation is that “intermittent fasting” is supposed to be healthy. (I’ll just cling to that idea so I can avoid worrying about yet another thing I “shouldn’t” be doing. Had enough of shoulds!)

I think you may be correct in thinking that the LDN, rather than *cause* him to feel more exhausted, it probably just allowed him to actually feel the state he’s been in all along.

I’ve had a similar experience recently with cranio-sacral therapy: after each session I feel just as exhausted as usual, but I’m calm and un-wired enough to fall into deep sleep rather than jitter around for a few hours before bouncing in and out of something that only the sleep-deprived would call sleep. The effects have lasted a couple of days before my usual nervous energy takes over again. Something similar happened while I was having gentle fascia release, initially twice a week and then just once a week as the effects became longer lasting. (Pain levels also dropped so dramatically that they become almost non-existent.) When I paused treatment for a while (thanks to lockdown), pain gradually came back after a few weeks and intensified, and my sleep went bats.

Restarting therapy at once a week only took a few weeks instead of a couple of months to get to a much improved state of pain-free- and slepp-full-ness.

However, I believe the effects are not only cumulative, but it seems each time I’ve taken a break from the therapy and started up again, it takes less time to regain the state of health I was at at the time of stopping, and it’s my sense my body/ANS/fasia/whatever it is, is learning a new, healthy, way of functioning, and like riding a bicycle, just needs a reminder and it quickly gets back into the flow.

My fascia release treatment stopped because my therapist has taken time off work, which is why I’m trying cranio, and finding it’s helping, in a somewhat similar yet also different way.

Does your son have any gentle body work treatments, particularly ones related to the fascia? (Emphasis on the “gentle”.) I wonder how it might compliment the LDN?

Andrea, I can relate to what Shelley writes about her son and your own comment. I’m getting a lot out of watching the parasympatheticsummit.com It’s one of those summits that’s free to view for 24 hours after each episode is broadcast and though it’s coming to an end, these summits usually do an encore weekend a week or two after the event is finished.

I watched an episode with Marco Ruggiero, which was so packed with information, I’ll have to watch that one again and take notes!

Anyway might be worth a look 🙂

Tracey

It’s amasing what doing a deep sinus wash before bed and making sure there are no smells in your room like purfume, blanket washed in scented soaps, ect. can do to help you sleep, if your sick from toxic mold anyways. a update on whats happening with me, I have bone cancer, most of my spine, make your doctors do the scans people, and if you lost everything and were forced to have medicad and medicare, you got to fight for it. Dr. Nancy Klimas is on the right tract but I dont know if they are really getting just how bad that leaky sinuses can affect the dura/myelin sleath and I know that is the path to my spinal cancer. my doctor have never seen anything like it before, pretty sure thats what happens when you spend 20 years getting direct hits to the brain .

correction, my spine and my skull, liver, bladder, lungs. trying to get them to actually look at my brain, stomach and bowels too.

Metabolism

. 2019 Nov;100S:153951. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2019.153951.

Neuroinflammation disorders exacerbated by environmental stressors

Abstract

Neuroinflammation is a condition characterized by the elaboration of proinflammatory mediators within the central nervous system. Neuroinflammation has emerged as a dominant theme in contemporary neuroscience due to its association with neurodegenerative disease states such as Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease and Huntington’s disease. While neuroinflammation often is associated with damage to the CNS, it also can occur in the absence of neurodegeneration, e.g., in association with systemic infection. The “acute phase” inflammatory response to tissue injury or infections instigates neuroinflammation-driven “sickness behavior,” i.e. a constellation of symptoms characterized by loss of appetite, fever, muscle pain, fatigue and cognitive problems. Typically, sickness behavior accompanies an inflammatory response that resolves quickly and serves to restore the body to homeostasis. However, recurring and sometimes chronic sickness behavior disorders can occur in the absence of an underlying cause or attendant neuropathology. Here, we review myalgic enchepalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), Gulf War Illness (GWI), and chemobrain as examples of such disorders and propose that they can be exacerbated and perhaps initiated by a variety of environmental stressors. Diverse environmental stressors may disrupt the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis and contribute to the degree and duration of a variety of neuroinflammation-driven diseases.

Keywords: Chemobrain “sickness behavior” stressors; GWI; ME/CFS; Neuroimmune; Neuroinflammation.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31610852/

Pituitary Tumors

These growths occur on the pituitary, a small gland located at the base of the brain that produces many hormones and controls other glands that produce hormones. There are many types of pituitary tumors. Some are small and may not cause any symptoms; others are large and can affect the eyesight in one or both eyes. These tumors can also create hormone disturbances that may affect growth, weight, sperm production, and ovarian function.

https://nyulangone.org/conditions/skull-base-tumors/types

Mol Neurobiol

. 2017 Nov;54(9):6806-6819. doi: 10.1007/s12035-016-0170-2. Epub 2016 Oct 20.

Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Hypofunction in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (ME)/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS) as a Consequence of Activated Immune-Inflammatory and Oxidative and Nitrosative Pathways

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27766535/

2020 Apr 29;7:162. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2020.00162. eCollection 2020.

Intravenous Cyclophosphamide in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. An Open-Label Phase II Study

Introduction: Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) is a disease with high symptom burden, of unknown etiology, with no established treatment. We observed patients with long-standing ME/CFS who got cancer….

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32411717/

Two experienced physicians state very explicitly that “solving poor sleep solves CFS/Fibro”.

One of these is Paul Swingle (in Canada, I believe). He uses neurofeedback. He has found a consistent pattern in CFS/Fibro patients – an excess of fast waves at the back of the head. He states that for most patients, correcting this improves their sleep, and makes their symptoms go away.

Another is Dr Smith (a retired NHS doctor in England who has I believe been mentioned on this blog before, a long time ago). He uses a combination of a sedating anti-depressant, and a sort of ‘Victorian’ regime of mild physical activity and an absence of ‘brain-work’, to improve sleep. Again, he states firmly that improving sleep is the key to improving the condition.

It should be said that these guys’ beliefs are based on treating thousands of cases, so it is not some thin, speculative study.

Recently, in addition, some Israeli neurofeedback researchers have developed a new neurofeedback protocol, for Fibro. They target the amygdala. Interestingly, they found that by training down amygdala activity, Fibro patients improved their condition….but that this improvement seemed to be mediated by improved sleep!

Thanks, Alex for the interesting info. 🙂 If anyone is interested the study ”

Volitional limbic neuromodulation exerts a beneficial clinical effect on Fibromyalgia” – is here https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30408596/