Mary Anne Fletcher (1937-2023) – In Memoriam

Mary Anne Fletcher (Image from NSU) Mary Anne Fletcher PhD passed away on April 27th. The longtime partner of Nancy Klimas, she was less in the public eye than Nancy but was a constant presence in the ME/CFS research arena. One of the early leaders on ME/CFS, her first ME/CFS paper was in 1990 – co-written with Nancy Klimas – she produced over 40 papers.

I only met Mary Anne a few times, but they were vivid. I remember – years ago – watching with a little awe as she boldly and vociferously called for NIH-funded treatment trials for ME/CFS.

She clearly had a very full life. She was active in civil rights during the 1950s and 60s, and during the campaign for the Equal Rights Amendment in the 1980s, during which she wrote a column for the National Organization for Women in Florida under the nom de plume Donna Quixote.

She loved animals – particularly dogs and horses and was clearly competitive – raising champion Samoyed and Norwich Terriers, competing in endurance equestrian events before turning to competitive carriage driving which she pursued into her 80s (!).

A leader to the core, she is survived by her two partners, Janet M. Canterbury, Ph.D. and Nancy Klimas, MD, her daughters, and numerous grandchildren and godchildren.

She’s the kind of person I would have loved to have known better. Thank you Mary Anne for your 40-years of dedication to people with ME/CFS, Gulf War Illness, and similar diseases.

Research Highlights from the Institute for Neuro-Immune Medicine at Nova Southeastern University Conference

Nancy Klimas, the leader of the Institute – which focuses on complex diseases like chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), Gulf War Illness, and long COVID – started the day off.

Dr. Klimas has been studying, treating and advocating for ME/CFS for decades.

Nancy Klimas noted that you can’t talk about ME/CFS or long COVID as autonomic or metabolic or immune diseases. All of them are present. These complex diseases are diseases of homeostasis; i.e. they affect multiple systems which, in turn, affect each other. That’s why they went to supercomputers to study them.

A (The?) Key Need for the ME/CFS Field

Nancy reiterated again the need to get an ME/CFS group in there with long-COVID patients in the NIH RECOVER Initiative, stating that it “can only move us if the trials allow an ME/CFS comparator group“, and asking them to at least “allow, if not require, an ME/CFS comparator group in the trials that are being planned. It is so, so very important”.

Note that right now, the RECOVER project won’t even “allow” an ME/CFS group in the RECOVER project. Advocates are pushing for RECOVER to simply “allow” an ME/CFS group in there. Could RECOVER be so uncaring and heartless to not even allow ME/CFS in there? Reportedly, some progress has been made, but time will tell.

The opposite is also true. ME/CFS researchers need to incorporate long-COVID patients into their studies, and she’s in the midst of a big one – funded by the CDC – that is. That’s “big” as in 750 people, but it’s STILL missing a big chunk of long-COVID patients (!). Nancy talked about her problems finding long-COVID participants at the IACFS/ME last year and apparently, the problem persists. The ME/CFS patients were eager – they knew her and were ready to participate but not so much the long-COVID patients. She needs at least 150 more long-COVID patients to complete was is looking like a fantastic study.

Long Awaited ME/CFS Clinical Trial – About to Begin…

Dr. Klimas’s long-awaited ME/CFS clinical trial looks like it’s about to happen.

Then it was onto the next delayed study! I’ve begun to think of the ME/CFS clinical trial as: “The study that’s always about ready to begin”. Three years ago, then COVID happened. I thought I heard last it was ready to go, but apparently now it really is ready to go. (“We’re about to launch this really cool study”).

Nobody in the ME/CFS field has brought this much data – millions of data points generated by measuring everything they could (gene expression, immune functioning, immune cells, neuropeptides, cytokines) 9 times before, during, and after a ride on the bike to exhaustion (or at least near it) – to a clinical trial.

This clinical trial is not backed by a hunch, a case report, or some doctor’s good ideas but by supercomputer findings. You only use a supercomputer when less than supercomputers won’t do (i.e. unless you have massive amounts of data) – and that’s what Nancy brought to this trial (and the similar Gulf War Illness trial).

All that data, plus a wide variety of treatment possibilities, were fed into a supercomputer, which was then asked – using chaos theory (no preconceived notions here) – what combination of treatments could turn this mess around. (I’m sure I’m greatly simplifying things.)

THE GIST

- Please see the Memorium to Mary Anne Fletcher – longtime ME/CFS researcher and partner of Nancy Klimas in the blog.

- Mary Anne Nancy Klimas noted that you can’t talk about ME/CFS or long COVID as autonomic or metabolic or immune diseases. All of them are present. These complex diseases are diseases of homeostasis; i.e. they affect multiple systems which, in turn, affect each other. That’s why they went to supercomputers to study them.

- She emphasized the need to get an ME/CFS group into the RECOVER Initiative for long-COVID patients, stating that this massive $1.15 billion effort “can only move us if the trials allow an ME/CFS comparator group”, and asking them to at least “allow, if not require, an ME/CFS comparator group in the trials that are being planned. It is so, so very important”.

- Her long-awaited and long-delayed ME/CFS clinical trial – I’ve begun to think of it as the trial that’s always about to begin – is actually about to begin.

- Nobody in the ME/CFS field has brought this much data – millions of data points generated by measuring everything they could (gene expression, immune functioning, immune cells, neuropeptides, cytokines) 9 times before, during, and after a ride on the bike to exhaustion (or at least near it) – to a clinical trial.

- It took a supercomputer to come up with the treatment regimen – staggered doses of etanercept to tackle neuroinflammation and mifepristone to reset the HPA access.

- A Phase I trial in GWI using the same treatment regimen “moved the needle in the right direction” and “made some real headway” and a modified Phase II trial is either underway or is on the books.

- The nice thing about these trials is that they’re potentially self-correcting; you give the patients the drugs, test the heck out of them, feed the data back into the computer, and let it self-correct. The potential for understanding this and other illnesses seems immense.

- Nancy Klimas has also put in an application to become one of the 3 NIH-funded research centers. Her approach is creative and novel and I, for one, hope she wins out.

- Moving onto mast cells, Nancy said they were “chronically leaky” in ME/CFS and noted that “serious headway” can be made in ME/CFS by quieting them down.

- Reduced blood perfusion to the brain makes it difficult to concentrate and produces brain fog, but “treatable points” are available and she pointed to luteolin, a mast cell stabilizer, that helps some people with ME/CFS. Much work in being done in this area.

- Travis Craddock asked why, with all the evidence of EBV reactivation in ME/CFS, the Rituximab study, which was designed to knock EBV-infected B-cells, didn’t work.

- First, he noted that the Institute’s genetic studies suggest that problems with the mucous membranes that protect the body from viruses may leave people with ME/CFS more open to viral invasions.

- His model showed that so long as other EBV reservoirs in the body are present, knocking the virus out only in the B-cells, allows the virus to remain in the body and soon reinfect the B-cells.

- His modeling efforts showed that combining Rituximab with an antiviral was much more efficacious. While the virus did persist, it was knocked down for long periods of time.

- Better EBV drugs may be on the horizon. An old drug called spironolactone led one University of Utah researcher to uncover a target that could stop EBV very early in its reactivation cycle. Plus, University of Ohio State researchers are attempting to recruit drug manufacturers to knock out a destructive EBV enzyme that’s been found in ME/CFS.

(One would have hoped the NIH – understanding the rigor (aren’t they all about rigor?), the depth, and the possibilities that this approach might present for other diseases might have funded this trial – but no – so far as I know, the ME/CFS Special Emphasis Panel (SEP) that rewards ME/CFS grants still refuses to fund any clinical trials. (C’mon guys – loosen up!) If I remember correctly, Nancy and colleagues raised the money for the trial on their own.

Nancy calls it their “moonshot” study and stated she was “really, really excited by it”. The Department of Defense (DOD) funded the Gulf War Illness trial using the same drugs. The DOD appears to be a tad less conservative and a tad more focused on getting patients better than the NIH.

First, the drug combo was tested in mice (yes, GWI has mouse models – thanks to DOD), and the mice responded as the model suggested. A Phase I trial in GWI “moved the needle in the right direction” and “made some real headway” (but apparently did not return the patients to “homeostasis”) and a modified Phase II trial is either underway or is on the books.

I wasn’t surprised to hear the first effort wasn’t a total success. I would have been surprised if it was, actually. So long as the models are good – and they should be getting better all the time – and Nancy can continue to get funded, this approach should be self-correcting. You give the patients the drugs, test the heck out of them, feed the data back into the computer, and let it self-correct. The potential for understanding this and other illnesses seems immense.

Note that Nancy’s using repurposed drugs that are readily available. If this thing works, there should be no problem getting them.

An NIH-Funded ME/CFS Research Center at INIM?

Dr. Klimas’s ME/CFS moonshot – it’s daring, creative, and novel – and deserves a chance. Will the NIH give it one?

It was GWI funding that allowed her to create the infrastructure she was then able to bring to bear on ME/CFS and produce this clinical trial. Now she’s applying to be one of the NIH-funded ME/CFS research centers, and I hope she gets it.

So far as research center grants go – these do not appear to be not great grants. One research effort I spoke is not going to apply because they felt the administrative requirements were just too much. David Systrom apparently backed off during the last round for the same reason.

Maureen Hanson’s group, in particular, though, has really made hay with these grants – putting out interesting finding after finding, and Ian Lipkin has produced some major papers. Nancy’s group – 16 faculty members and 60 members in all – is now huge (by ME/CFS standards). If any group can productively handle the administrative load, one would think hers could.

She’s doing “moonshot” work that’s creative and novel, though – too novel for the NIH? We shall see. I would hope that the NIH would look at what she’s doing – see that she’s zeroed in on finding data-driven treatments – something they know this disease needs – and gives it to her.

The NIH’s refusal to fund clinical trials through the ME/CFS SEP, after all, is because they don’t feel the field is “ready”. They’re being careful – they’ve seen fields that moved too quickly set back for considerable periods, but Nancy comes loaded with data. That seems different.

Nasty, Nasty Mast Cells

“Chronically leaking” mast cells appear to be playing a big role in these diseases.

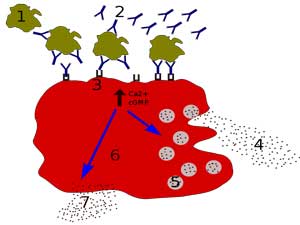

Referencing Theoharides, who did a sabbatical at their lab and came to stay, Nancy was onto mast cells, which she said were “chronically leaking a lot of nasty toxic mediators into the bloodstream” (now there’s a vivid image) in ME/CFS. These mast cells are apparently everywhere in the body. An activation here, and activation there and pretty soon you could have something like ME/CFS. Every day in the clinic, she said, they “can make serious headway” when they quiet down mast cells in ME/CFS and long COVID. (A mast cell blog is coming up).

Next, she was onto the problems with blood perfusion to the brain. The brain is a finely-tuned machine that quickly delivers oxygen and glucose to areas in need. If you’re doing math, for instance, it will shunt blood to the part of the brain that does calculations. Except not so much in ME/CFS, where studies have shown that stressing one part of the brain does not necessarily lead to increased blood flows to it. No wonder brain fog is prevalent.

She stated, though, that treatable points in the brain that calm down the mast cells exist. Glutathione – the major antioxidant in the body – has trouble getting through to the brain, but luteolin, a mast cell stabilizer, can. A lot of work outside of ME/CFS is being done to find ways to deliver antioxidants and other anti-inflammatories to the brain.

The Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) Conundrum or How to REALLY Knock EBV Down

EBV is like a prizefighter that just will not go down. New approaches, though, have the potential to keep it contained for good.

Travis Craddock – the head of the modeling department – noted that despite the fact that EBV and herpesvirus reactivation appears to be present, antiviral drugs have limited effects. Craddock questioned if that’s due to the antiviral’s inability to completely wipe out the viral population, and then noted that EBV infects and hangs out in B-cells. The Rituximab trial tried to wipe out the B-cells in hopes of removing the virus. The first, small trial showed efficacy, but the larger study failed (miserably).

The question that nagged at them was: why? We have EBV reactivation and we know that EBV loves to hang out in B-cells – so why would a trial that removed those B-cells fail? Craddock proposed it just didn’t go far enough. Recent studies have found EBV in T and NK cells and epithelial cells. HHV-6 can get into NK, dendritic, epithelial cells, and the salivary glands. Given that – why would we expect a drug aimed at just one of those cells to work?

Mucous-Deficient ME/CFS Patients Give Viruses a Leg Up?

The other big question is why people with ME/CFS don’t recover from a virus that’s found in 95% of the population. Asking what is different about them, Craddock pointed to an INIM genetic study (unpublished) which found alterations in the genes that produce salivary and nasal mucous; i.e. the protective layer that pathogens and chemicals must surmount to get into the body, and which harbor pathogens as well. Craddock suggested that inadequate mucous layers might result in low-grade inflammation in these herpesvirus-laden epithelial cells that causes them to release herpesviruses into the body – jumpstarting the reactivation process.

The Model Builder at Work

Travis Craddock builds models – the kinds of models that need supercomputers to run.

The obvious next thing for Craddock to do – because that’s what he does – was build a model. Together with a Boston researcher, he built a mathematical model that took into account the saliva, the damaged mucous layer, the herpesviruses, B- and T-cells, and simulated the systems involved. Then they altered the parameters of the model many times.

The difference in their model was that they started out with an EBV infection in both the epithelial and the B-cells. The model showed the infection spiking and spreading and then settling down – with a reservoir established in both the epithelial and B-cells.

Next, they added several Rituximab doses a year. Sure enough, the virus dropped to nothing in the B-cells but then bounced back as the EBV emerged from the epithelial cells and reinfected the B-cells. It didn’t take too much time for the virus to return to its full strength.

Then, they changed the effectiveness of the antiviral from 100% to 99% down to 85% in the model. Only when the antiviral was nearly completely effective (99%-100%) did EBV get knocked down for long. The dose of antiviral needed to achieve that degree of effectiveness, however, would leave it toxic to humans. With the antivirals we have, knocking down EBV for good looked like an impossible task.

But then, they asked, what if you add a B-cell suppressor like Rituximab to the mix? Adding a timed B-cell treatment to an antiviral basically flatlined the virus – it was no longer able to reactivate. Craddock stated the model – which they are continuing to improve – suggested the approach could theoretically produce a long-term reduction – not a forever reduction, but a long-term reduction of viral load.

These are the kinds of novel approaches we will need. Prusty said it well – we are going to need a set of targeted treatments that match the complexity of the disease. No one silver bullet will do – but a couple might.

Better EBV Drugs on the Horizon?

The remarkable spironolactone saga demonstrates that better EBV drugs might not be that far in the future. In an attempt to knock out EBV in its earliest stages of reactivation, Sankar Swaminathan MD, an infectious disease researcher at the University of Utah, uncovered an old mineralocorticoid drug called spironolactone that was able to do that – but was too toxic to be used regularly. That drug, however, lead him to uncover a key aspect of early EBV reactivation, which he is now trying to target with drugs. Success could lead to a new, more effective generation of EBV-specific drugs.

Plus the Ariza-Williams team at Ohio State University published a paper alerting drug-makers to the potential that tamping down the EBV dUTPase enzyme may hold in treating herpesvirus infections.

Lastly, I was told that a potentially better EBV drug, that was developed but failed to get much interest, was looking more hopeful with the emergence of herpesvirus reactivation in long COVID. Time will tell, but suddenly the potential for a better herpesvirus drug seems greater than ever.

Conference Video

Watch a video of the conference – which also included some talks on healthy homes, getting better sleep, and nutrition here.

Health Rising’s Donation Drive Update

Our summer donation drive is blasting off!

Thanks to the 100-plus people who have provided over $7,000 in support, Health Rising’s summer donation drive is blasting off.

This blog provides a nice example of our ability to weave different findings together to provide a more complete and compelling picture that’s paving the way for possible new treatment futures. If that’s the kind of work you want to see, please support us.

Appreciate this reporting, Cort!

Do you have any insight or further information from the ME cohort that was approved in RECOVER after the feature centering Prof. Leonard Jason shared the news back in March?

(https://www.newswise.com/coronavirus/researcher-leonard-a-jason-pushes-discovery-on-long-covid-mecfs)

Any information you can share to the community that we may not be privy to?

All I know is that one hurdle was passed and another remains! The first hurdle was a biggie though. I’m waiting to hear from Solve ME on this. They’ve been moving this along.

Do long Covid patients need to live in Florida to be included in Nancy’s study? I have children with ME/CFS and I have had long Covid for 18 months, so I’m really invested in her work and would love to be a participant. Any leads for how to contact her would be great. Thanks!

https://www.nova.edu/nim/index.html

This should get you to the Institute for Neuro-Immune Medicine at Nova Southeastern University

Looks like they do televisits

They only do televisits after the first appointment, which must be in person. No idea if that has anything to do with the study though.

That’s a great question. This is a great study- it’s big, its comprehensive and it includes both ME/CFS and long COVID patients. It’s a real opportunity for both patient groups! Good luck!

INIM Research Studies

Tel: 305-275-5450

Email: INIMresearch@nova.edu

I’m curious how the mouse are induced into an MECFS-like state

Super interesting, thank you.

Luteolin is so great for some. But, for those of us with slow COMT it can slow it down more and create agitation or anxiety. SUCH a bummer, as I’ve seen so many good studies about it.

I’m currently in an EBV activation flare. I’ve seen good studies on andrographis to help treat it. Trying that.

Interesting. I tried Luteolin with great hope (as I have some clear mast cell involvement) and had an opposite reaction–intense, overwhelming sleepiness. I kept at it for a month in case it was a die-off reaction of some kind, but there’s no doubt it was the cause. Took a while to get back to base line. For brain fog, I have found high-dose liposomal C and EPA only (without DHA) to be helpful but of course we are all so different and in different phases. Really curious what it is about luteolin that made me feel like I’d taken a double-dose of sedative.

Hi Cort.

I just wanted to tell you what I have used to knock my EBV load down; not out, but down and improve my ME/CFS symptoms. I was diagnosed by a regular medical doctor with ME/CFS many years ago. My downward spiral with this disease and finally getting a diagnosis of ME/CFS took many years and is too long a story to tell. But, after researching a lot about ME/CFS, I came across Dr. Lerner’s research and protocol; using Valtrex. I tried it with doctor supervision but it led to brain toxicity for me. I then tried high dose Monolaurin and after many months of ramping up to 8000mg daily and staying on high dose Monolaurin for 1 year, I found it effective for temporarily eliminating my reactivated EBV with absolutely no toxicity or side effects. Now it’s important to note that I am currently on a daily dose of 2000mg of Monolaurin because when I try to stop taking Monolaurin, after a few weeks my cold sores always come back. When

I continue taking 2000mg of Monolaurin daily, I don’t get cold sores. Monolaurin

is effective for me at knocking down the virus but not permanently eliminating it. After getting the EBV load down and changing to a Vegan Diet, I have had many improvements with my energy, body aches, and mental focus and instead of being house-bound, I can be a little more active and don’t get out of breath so easily. Monolaurin is not a ME/CFS cure but it did help me.

Hi Cort, I just visited Phoenix Rising and noticed that you were going to become the forum leader and owner of PR and that the current board had all resigned. Are you merging Phoenix Rising with Health Rising? I thought PR was a nonprofit. I was puzzled about the term owner.

Yes, Health Rising is now in charge of Phoenix Rising. The board – which was on its last legs – requested that HR take over PR. I agreed and after PR’s financial assets were disbursed to other non-profits, HR became responsible for PR.

congrats, hope the meld goes well

Thank you for another great article, Cort! Don’t know what we would do without you. Using your own personal battle to help millions of sufferers is a testament to your character. Your long history of dedicating yourself to raising awareness has erupted with long Covid. Your site is now appearing and being shared on so many platforms and engines. I hope you realize how much this means.

Thanks! I, of course, am very glad to hear the site and the blogs are showing up in many places :). Thanks for letting me know!

Nancy Klimas has also put in an application to become one of the 3 NIH-funded research centers. Her approach is creative and novel and I, for one, hope she wins out.

Is it the case then, that no matter how many, what quality of the groups that apply, the NIH still wants to keep it just at 3 ? It sounds like deliberately containing rather than building up. I thought that, in my humble opinion, the 10 who applied at the first go were all perfectly decent.

Yes – we’re still at three! We have this wonky funding mechanism where we are dependent up on bunch of Institutes – none of which are responsible for us – to join together to provide funding.

With several Institutes that did provide some funding actually declining to provide any funding for ME/CFS this time around we’re dependent on fewer institutes. Thankfully, NIAID and NINDS stepped up their funding so that we can, at least, continue with the 3 centers we have.

I had, in my naivete, thought that the emergence of long COVID as a major issue would help with funding but it has not. It’s rough over there there’s no doubt about it but I know of NIH officials who are very sympathetic to our cause.

Still, we are still stuck. Solve ME has begun a campaign to create a new NIH Institute to house ME/CFS and other diseases. That’s a long-term goal but I applaud them for that effort and will report on it. It would help this field GREATLY, as well, to get into the RECOVER Initiative and Solve ME is also working on that and one hurdle has been passed.

Plus, a Research Roadmap and Strategic plan for ME/CFS that’s designed to increase our support within the NIH is underway. So, quite a few things are going on over there.

hi Cort, is nancy klimas now really going to start finally with her combo treatment on ME/cfs? you wrote she could not fing enough long covid patients. and over the many many years, i have read so often that she would start with the trial… I have now something like first see and then believe….

do you know on how many ME/cfs patients, Long covid patients, ?healthy controls? this study will be?

thanks!!!

I really admire Nancy’s advocacy for our illness but I think it’s fair to say I have been pretty disappointed in her research outputs over the past 20 years which always seemed to promise much, but deliver very little.

Maybe I am being unfair.

I feel the same…. so often study would get started and nothing, also a long term sufferer and i decline further and further…. can in my country not survive alone and it is still cfs with get and cbt as if i did not had that allready in 1994…declined rapidly with it…

over all the time, when i got internet, in general, how many broken promisses, it is crazy….every time hope to just fall back.

Hi Konjin! It’s been a while. I’m sure it will be a small trial – if I’m not wrong it was privately funded – and it only involves ME/CFS patients. It sounds like it’s going to actually begin and who knows, maybe Nancy’s results with the Gulf War trial will help our trial – maybe the delay will end up being a good thing…

I imagine that Nancy and her team have also been working hard on the NIH Research Center’s grant application – which is apparently now in. Good luck to them 🙂

thanks Cort! sadly again a small trial…but at least something…

that her studus on GWI will help us, I am totally not shure. Also GWI research gets there deserved money (I do not know how much but at least more then ME/cfs- when i looked at her page.

the strange thing is longer time afo i mailed to donate for her ME/cfs research but even never got an answer 🙂 so private funding…

sorry, verry ill…many typ mistakes…

Why mefipristone to target HPA axis? Isn’t it an abortion pill?

It also effects the HPA axis! Drugs do that – effect different things – all the time actually –

I’m part of this Long Covid trial! I heard they were having a really hard time finding people willing to participate since it’s tied to the government. Honestly, it was only through my intense research that I found it. I called about it in February and it took 2 months before I got a call back about it. I think they should advertise for it more- go on the news and make headlines about it so people can find out! It’s been 6 months since my testing and I still haven’t gotten some of the results, because it’s expensive and they are waiting for more participants to add. It’d be sad if the CDC gets the impression there aren’t many with LC and lose interest in figuring it out.