Dr. Courtney Craig used traditional and integrative therapies to recover from ME/CFS.

Dr. Courtney Craig is back! A trained dietitian and chiropractor, Dr. Craig combines lived experience (she had ME/CFS for many years) with a zest for clinical science.

Dr. Craig graduated with honors from the University of Bridgeport’s Human Nutrition Institute Master’s program, studied at the Technical University of Munich, Germany with a focus on nutrition and biomedical research, and was a visiting scientist at Cornell’s Center for Enervating NeuroImmune Disease under Maureen Hanson.

She has also contributed many blogs to Health Rising. (See list below.)

Carnivore Diets

Carnivore diets have recently exploded in popularity. Glimpse reported that search engine interest in carnivore diets grew 94% over the past year. This is, in part, due to the emergence of “meatfluencers” – high-profile advocates, such as podcasters, athletes, and actors – who’ve been extolling the diet’s positive effects on weight loss, increased energy, and mental clarity.

The diet’s simplicity is certainly a factor, and people can lose weight on it. Still, Dr. Craig warns that while some people with chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) or long COVID may experience temporary improvement, a carnivore diet may not be the best approach…

Onto the blog! (Images, links and the GIST from Cort)

Why the Carnivore Diet Could Backfire in ME/CFS and Long COVID: A Closer Look at the Risks

Ancestral-style diets have long held appeal for those with ME/CFS. Dr. Sarah Myhill’s “Stone Age diet” is one early example. But the newest trend—the all-meat carnivore diet—goes far beyond any traditional eating pattern. Despite the hype, there’s no historical precedent for a population thriving on zero plants. And for post-viral conditions, this restrictive approach may do more harm than good.

Let’s start with a critical distinction that often gets overlooked:

Carnivore diets are all the rage – but are they good for people with ME/CFS/FM and long COVID.

THE GIST

-

- Driven by “meatfluencers”, carnivore diets have soared in popularity recently. Advocates cite weight loss, increased energy, and mental clarity.

- Nutritionist and former person with ME/CFS, Dr. Courtney Craig warns, though, that they are not the answer for people with ME/CFS and long COVID and could do more harm than good.

- She points out that carnivore diets (primarily meat, organ meats, animal fats, eggs, and sometimes dairy) are an extreme form of keto that includes: 60–90% fat, 10–40% protein, 0% carbohydrates (no fiber, no plant foods, no polyphenols).

- While a well-constructed ketogenic diet should include non-starchy vegetables (e.g., leafy greens, zucchini, broccoli), fermented foods (e.g., sauerkraut, kimchi), herbs and spices rich in polyphenols and flavonoids, carnivore diets contain none of these.

- One of the most concerning effects of the carnivore diet is the complete elimination of fermentable fiber. This fiber is the primary fuel source for butyrate-producing bacteria, which are already low in ME/CFS, and which helps protect the gut lining, reduce inflammation, and even helps with sleep.

- High saturated fat intake, without the buffering effects of fiber, can increase cardiometabolic risk, including an increased risk of insulin resistance, which some studies suggest is also increased in ME/CFS and long COVID.

- Carnivore diets further reduce microbial or gut flora diversity which is consistently low in both ME/CFS and long COVID

- One often-overlooked consequence of the carnivore diet is its impact on hydration status—an especially important consideration for people with orthostatic intolerance, POTS, or low blood volume.

- Dr. Craig, those who initially improve on carnivore diets likely have an underlying gut dysfunction (multiple food intolerances, digestive sluggishness, or microbial imbalance) that makes plant foods harder to tolerate in the short term, rather than a biological need for a meat-only diet.

- Some people report symptom relief on a carnivore diet because they are avoiding lectins – a class of carbohydrate-binding proteins found in many plant foods, especially legumes, grains, and nightshades. When eating in large amounts or when improperly prepared, lectins can provoke inflammation or gastrointestinal discomfort in sensitive individuals.

- It’s important to emphasize that these effects are dose-dependent and are largely mitigated by proper cooking and food preparation. No high-quality studies have linked lectin intake to chronic illnesses. With time and targeted support for the gut barrier, many people can reintroduce cooked lectin-containing foods without issue.

- A short carnivore stint may serve as a functional elimination diet for some. But without the planned reintroduction of low-FODMAP, low net-carb, polyphenol-rich foods, the long-term risks are too great, especially for those with already fragile physiology.

- A more strategic approach to diet would include low-FODMAP, low-carb, or ketogenic diets that include resistant starches (tailored to individual tolerance) and refeeding strategies that support microbial repair rather than prolonged suppression.

- Health Rising readers can get 10% off any of Dr. Craig’s nutrition video courses by using the code Rising10, Her latest course is on the gut. :

A Carnivore Diet Is Ketogenic, But a Ketogenic Diet Is Not Carnivore

I’ve long promoted therapeutic ketogenic diets for post-viral conditions like ME/CFS and long COVID, not because they’re trendy, but because they target key mechanisms: mitochondrial dysfunction, chronic inflammation, and impaired energy metabolism.

A ketogenic diet is defined by its ability to induce nutritional ketosis, typically through a macronutrient ratio of: 70–80% fat, 10–20% protein, 5–10% carbohydrates (usually 20–50 grams of net carbs* per day). *net carbs is total carbohydrate content minus the fiber.

Carnivore diets are all the rage – but are they good for people with ME/CFS/FM and long COVID?

In contrast, a carnivore diet is an extreme form of keto that includes: 60–90% fat, 10–40% protein, 0% carbohydrates (no fiber, no plant foods, no polyphenols). The diet is primarily meat, organ meats, animal fats, eggs, and sometimes dairy. Strict carnivore diets even eliminate spices!

While both diets can promote nutritional ketosis, carnivore excludes all plant-based foods, which are essential in a therapeutic keto approach. A well-constructed ketogenic diet should include: non-starchy vegetables (e.g., leafy greens, zucchini, broccoli), fermented foods (e.g., sauerkraut, kimchi), herbs and spices rich in polyphenols and flavonoids.

These food components are critical for:

- Gut microbiome diversity

- Butyrate production

- Reducing oxidative stress and systemic inflammation

- Supporting gut-brain-immune interactions.

Eliminating these foods, as the carnivore diet does, risks undermining the very systems that need the most support in post-viral recovery. Here are 5 specific reasons this isn’t a good dietary choice:

-

Butyrate Is Already Low in ME/CFS—And Carnivore Likely Makes It Worse

One of the most concerning effects of the carnivore diet is the complete elimination of fermentable fiber, the primary fuel source for butyrate-producing bacteria.

Butyrate is produced when gut microbes ferment certain dietary fibers, especially resistant starches, found in:

- Cooked and cooled potatoes or rice

- Green bananas

- Legumes (if tolerated)

- Certain whole grains (if tolerated).

These are completely absent in a carnivore diet.

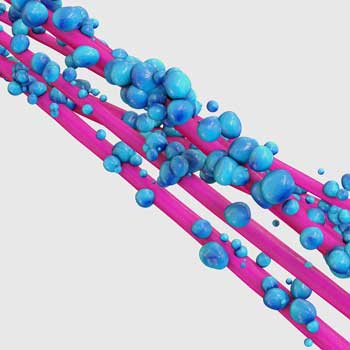

Butyrate levels have been low in several ME/CFS studies.

Butyrate isn’t just a byproduct of fiber fermentation—it’s a critical postbiotic that helps maintain gut barrier integrity, reduce neuroinflammation, and regulate immune tolerance. Butyrate helps modulate the immune system by reducing excessive inflammation and promoting tolerance, supports the integrity of the gut lining by nourishing intestinal cells, and acts as a fuel source for colonocytes. It also plays a role in energy metabolism and may help alleviate low-grade inflammation, a hallmark of post-viral illness.

A 2023 paper found that individuals with ME/CFS had a significantly diminished capacity for microbial butyrate synthesis, as well as altered bacterial network structure and correlations between low butyrate-producing capacity and fatigue severity (Guo et al, 2023). Multiple studies have shown reduced levels of butyrate-producing bacteria (Giloteaux et al, 2016; Liu et al, 2023).

Butyrate deficiency also impairs deep sleep and contributes to unrefreshing rest. Butyrate is not just a gut metabolite; it crosses into circulation and interacts with sleep-regulating centers in the brain. Studies in animals show it can deepen non-REM sleep, and emerging human data suggest it plays a role in sleep quality and recovery (Szentirmai, 2019).

In individuals already struggling with post-viral dysbiosis, this lack of fermentable substrate can result in:

- Further butyrate depletion

- Poorer sleep regulation

- Increased gut permeability

- Heightened inflammation and immune dysfunction.

Fermentation isn’t just a digestive nuisance, it’s essential to host-microbe symbiosis. While reduced fermentation may temporarily reduce bloating, the long-term consequence is microbial starvation, not healing.

-

Cardiovascular Risk Is Real—Especially Without Fiber

Saturated fat is not inherently harmful, but in the absence of fiber and plant compounds, its impact changes, particularly in people with post-viral insulin resistance.

Insulin resistance is well-documented in ME/CFS and long COVID. Studies show impaired glucose uptake, elevated insulin, and mitochondrial inflexibility—even in lean individuals (Wu et al, 2023; Cordero et al, 2010).

In this context, high saturated fat intake, without the buffering effects of fiber, can increase cardiometabolic risk. Fiber helps by:

- Binding bile acids and lowering cholesterol absorption (Brown et al, 1999)

- Feeding butyrate-producing bacteria that improve insulin sensitivity (Weickert & Pfeiffer, 2008)

- Blunting postprandial (after meal) glucose and lipid spikes (Weickert & Pfeiffer, 2008).

People with ApoE4 genotypes are particularly vulnerable. They experience greater LDL-C increases and more inflammation on high-saturated-fat, low-fiber diets (Corella & Ordovás, 2014). Up to 25% of the general population has this genotype. For post-viral patients, this presents a compounded risk.

-

Microbiome Diversity Is Already Compromised in Post-viral Illness—And Carnivore Likely Starves It Further

Loss of microbial diversity is a consistent finding in both ME/CFS and long COVID (Giloteaux et al, 2016; Su et al, 2022). Studies have shown:

- Reduced Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and other butyrate producers

- Overgrowth of proinflammatory and opportunistic Enterobacteriaceae

- Increased gut permeability.

Low levels of healthy gut bacteria such a F. prausnitzzi have been found.

Rebuilding a healthy and resilient microbiome is a foundational goal. But doing so requires specific substrates—not just general calories, but fermentable fibers and plant-derived compounds that selectively nourish beneficial species.

Polyphenols, for example, act as selective prebiotics. They feed beneficial microbes while actively suppressing pathogenic strains. This targeted support helps restore microbial balance, enhance barrier function, and reduce systemic inflammation.

Rich polyphenol sources include:

- Berries

- Green and black tea

- Extra virgin olive oil

- Herbs and spices

- Dark chocolate (in moderation).

These compounds, combined with resistant starch and low-FODMAP vegetables, help restore microbial diversity. A carnivore diet, by excluding all plant foods, removes the very tools needed to restore gut health. In this way, it may not just fail to repair dysbiosis—it may reinforce and prolong it.

-

Carnivore Diets Risk Key Micronutrient Deficiencies

While some proponents argue that meat provides all essential nutrients, research suggests this isn’t the case for most real-world carnivore diets. Without plant foods, individuals may become deficient in nutrients like:

- Magnesium – required for mitochondrial function and commonly low in ME/CFS

- Vitamin C – absent in muscle meats and critical for immune resilience and collagen synthesis

- Folate and potassium – abundant in plant foods but limited in meat-only diets

- Vitamin K – important for coagulation balance and is synthesized by gut microbes. Only contained in leafy greens, animal sources of K include liver and fermented dairy, but not all carnivore adherents consume these.

A 2020 review noted that a long-term carnivore diet may require supplementation to meet micronutrient needs—something many followers don’t realize (O’Hearn, 2020). Any super restrictive diet carries the risk of micronutrient deficiency over time.

-

Carnivore Diets Can Undermine Hydration—A Problem for Orthostatic Intolerance

One often-overlooked consequence of the carnivore diet is its impact on hydration status—an especially important consideration for people with orthostatic intolerance, POTS, or low blood volume.

On average, about 20% of daily water intake comes from food, primarily fruits and vegetables. When these water-rich plant foods are eliminated, total hydration drops unless water and electrolyte intake are consciously increased.

Carnivore diets also tend to promote fluid and sodium loss, especially in the first few weeks, due to glycogen depletion (which releases stored water). For individuals with autonomic dysfunction, this can worsen symptoms. In clinical settings, people with ME/CFS and long COVID are often encouraged to increase both fluid and electrolyte intake, especially sodium and potassium.

A carnivore diet, if not carefully managed, can undermine this strategy and increase the burden on already impaired autonomic regulation systems.

Why Some People Feel Better on Carnivore

Dr. Craig believes a positive response to a carnivore diet may reflect an underlying gut dysfunction.

Despite all of this, some people report dramatic symptom relief on a carnivore diet. What’s going on here? A positive response provides a useful clinical clue: it reflects underlying gut dysfunction, not a biological need for meat-only eating. These individuals often have multiple food intolerances, digestive sluggishness, or microbial imbalance that make plant foods harder to tolerate in the short term. These digestive issues are big players in the manifestation of symptoms.

Temporary improvements often stem from:

- Reduced FODMAP load (less fermentation and bloating)

- Simplified digestion (especially helpful with SIBO or low stomach acid)

- Lower histamine/salicylate/oxalate burden (common in MCAS).

These effects offer a gut rest, not a fix. They temporarily reduce symptom burden by limiting exposure to compounds that irritate an already sensitive digestive system. A low-FODMAP ketogenic approach or carefully structured elimination diet could achieve similar benefits without sacrificing long-term gut and metabolic health. In this way, a short-term carnivore diet could act as a sort of litmus test: if someone feels dramatically better on carnivore, it may point to deeper issues with digestion, food tolerance, or microbiome balance that warrant further investigation and support.

What About Lectins?

Another reason some people report symptom relief on a carnivore diet may involve lectins—a class of carbohydrate-binding proteins found in many plant foods, especially legumes, grains, and nightshades. Lectins are part of a plant’s natural defense system and, in large amounts or when improperly prepared, may provoke inflammation or gastrointestinal discomfort in sensitive individuals (Vasconcelos & Oliveira, 2004).

Lectins (found in beans, legumes and other foods) can irritate the stomach lining in some people. No high-quality studies, though, have connected them with chronic illnesses. (Image from Bean-appreciator-CC0-via-Wikimedia-Commons)

In those with increased intestinal permeability, a feature observed in both ME/CFS and long COVID (Su et al, 2022; Giloteaux et al, 2016), lectins may have a greater opportunity to interact with the immune system. Some in vitro and animal studies suggest that certain lectins, particularly those from raw legumes or grains, can activate toll-like receptors, promote cytokine release, or disrupt tight junction proteins (Wang & Yu, 2004; Lajolo & Genovese, 2002).

However, it’s important to emphasize that these effects are dose-dependent and largely mitigated by cooking and proper food preparation (Pusztai et al, 1999).

Despite popular claims, there are currently no high-quality human clinical trials linking lectin consumption to chronic disease symptoms in the general population. In fact, many lectin-rich foods, when cooked, are associated with positive health outcomes, including improved metabolic and cardiovascular markers (Becerra-Tomás et al, 2022). The problem, therefore, may lie not in lectins themselves but in individual vulnerability, particularly in those with MCAS, dysbiosis, or an impaired gut barrier.

In these individuals, removing high-lectin foods may temporarily reduce symptom burden. But much like with FODMAPs, the goal isn’t lifelong avoidance. With time and targeted support for the gut barrier, many people can reintroduce cooked lectin-containing foods without issue. A restrictive approach like carnivore, however, offers no pathway for reintroduction—only continued avoidance.

Short-Term Carnivore Might Have a Place—But Refeeding Is Critical

A short carnivore stint may serve as a functional elimination diet for some. But without the planned reintroduction of low-FODMAP, low net-carb, polyphenol-rich foods, the long-term risks are too great, especially for those with already fragile physiology.

Bottom Line: There Are No Shortcuts in Post-viral Recovery

Carnivore might offer temporary reprieve, but it’s not a sustainable or safe solution for most with post-viral syndromes. The long-term health impacts of such a restrictive, plant-free diet have not been thoroughly studied in ancestral populations or clinical settings. In contrast, ketogenic and low-FODMAP diets have been examined in numerous trials and shown to be both safe and effective when properly implemented.

A more strategic approach supports butyrate production and microbial resilience through:

- A low-FODMAP, low-carb, or ketogenic diet that includes plant polyphenols

- Resistant starches, tailored to individual tolerance

- Refeeding strategies that support microbial repair rather than prolonged suppression.

A short-term carnivore diet may serve as a brief elimination phase for identifying intolerances, but it must be followed by a structured reintroduction of plant-based foods to support long-term gut and immune health. Without this, the risks outweigh the perceived short-term benefits.

Ten Percent Off On Dr. Craig’s Nutrition Video Courses for Health Rising Readers

Health Rising readers can get 10% off any of Dr. Craig’s nutrition video courses by using the code Rising10, Her latest course on the gut features:

• Gut healing protocols for dysbiosis, SIBO, MCAS, IBS, and more

• It focuses almost entirely on dietary changes, not supplements

• Step-by-step reintroduction strategies for low-energy learning.

*See references below

______________________________

Courtney Craig recovered from ME/CFS/FM using both conventional and integrative medicine.

Dr. Courtney Craig D.C. was first diagnosed with CFS as a teen in 1998, and recovered in 2010 utilizing both conventional and integrative medicine.

Trained as a doctor of chiropractic and nutritionist, she now provides nutrition consulting and blogs about what she’s learned at www.drCourtneyCraig.com/

Dr. Craig’s Health Rising blogs

- Overcoming Depression with Ketamine, and Her Online Diet Course for ME/CFS, FM and Long COVID

- “Clean Energy”: Can a Ketogenic Diet Help with ME/CFS and Fibromyalgia?

- Breaking the BDNF Blues: Dr. Courtney Craig D.C. on Natural Ways to Raise BDNF Levels in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome

- A Closer Look at Natural Killer Cells In Chronic Fatigue Syndrome and Three Natural Ways to Boost Them

- Dr. Craig on Fasting for Better Health in Fibromyalgia and Chronic Fatigue Syndrome

References

- Wu H, Aguilar EG, Tian L, et al. Inflammatory and metabolic signatures in post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC). Cell Metab. 2023;35(1):28-46.e5. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2022.12.001

- Cordero MD, Cano-García FJ, Alcocer-Gómez E, et al. Clinical symptoms in fibromyalgia are better associated to lipid peroxidation levels in blood mononuclear cells rather than in plasma. PLoS One. 2010;5(4):e10228. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0010228

- Brown L, Rosner B, Willett WW, Sacks FM. Cholesterol-lowering effects of dietary fiber: a meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;69(1):30-42. doi:10.1093/ajcn/69.1.30

- Giloteaux L, Goodrich JK, Walters WA, et al. Reduced diversity and altered composition of the gut microbiome in individuals with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Microbiome. 2016;4(1):30. doi:10.1186/s40168-016-0171-4

- Weickert MO, Pfeiffer AF. Metabolic effects of dietary fiber consumption and prevention of diabetes. J Nutr. 2008;138(3):439-442. doi:10.1093/jn/138.3.439

- Szentirmai É, Millican NS, Massie AR, Kapás L. Butyrate, a metabolite of intestinal bacteria, enhances sleep. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):7035. Published 2019 May 7. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-43502-1

- Corella D, Ordovás JM. Aging and cardiovascular diseases: the role of gene-diet interactions. Ageing Res Rev. 2014;18:53-73. doi:10.1016/j.arr.2014.06.006

- O’Hearn A. Can a carnivore diet provide all essential nutrients? Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2020;27(5):312–316. doi:10.1097/MED.0000000000000576.

- Vasconcelos IM, Oliveira JTA. Antinutritional properties of plant lectins. Toxicon. 2004;44(4):385-403. doi:10.1016/j.toxicon.2004.05.005

- Su Y, Yuan D, Chen DG, et al. Multiple early factors anticipate post-acute COVID-19 sequelae. Cell. 2022;185(5):881-895.e20. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2022.01.014

- Giloteaux L, Goodrich JK, Walters WA, et al. Reduced diversity and altered composition of the gut microbiome in individuals with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Microbiome. 2016;4(1):30. doi:10.1186/s40168-016-0171-4

- Wang Q, Yu LG. Interaction of dietary lectins with the gastrointestinal tract and their biological effects. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2004;8(1):123-129. doi:10.1016/j.cbpa.2003.12.006

- Lajolo FM, Genovese MI. Nutritional significance of lectins and enzyme inhibitors from legumes. J Agric Food Chem. 2002;50(22):6592-6598. doi:10.1021/jf020191k

- Pusztai A, Grant G, Spencer RJ, et al. Kidney bean lectin-induced Escherichia coli overgrowth in the small intestine is blocked by gut fermentation and reversed by simple sugars. J Appl Microbiol. 1999;86(3):408-414. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2672.1999.00671.x

- Becerra-Tomás N, Papandreou C, Salas-Salvadó J. Legume consumption and cardiovascular risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2022;62(4):1014-1023. doi:10.1080/10408398.2020.1825921

I’ve tried numerous different diets over the 9 years I’ve been ill . Fasting and the carnivore diet made me feel absolutely horrendous . Never again if I can help it !

Carnivore is a huge problem, as is keto, for some people if you transition quickly. It takes MONTHS for some people to adapt. Change should be slow. This includes intermittent fasting, same issue.

An important addition to my comment. Prolonged fasting is probably a very bad idea in ME or CFS most of the time. Our energy production is sufficiently deranged that we are more likely to run into problems. This is my opinion, and needs empirical testing.

I also don’t recommend prolonged fasts. If at all, they MUST be done under supervision!

But I thought I’d put this study out there if anyone hasn’t seen it yet:

Improvements during long-term fasting in patients with long COVID—a case series and literature review:

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10651743/

Dr. Courtney, May I ask you a personal question? Are you a vegetarian? Or do you eat meat?

And don’t forget the influence of gut bacteria. In lactose intolerance, it is known that these people have lack of a certain enzyme or have less of it that can break down lactose proteins. Many ME patients suffer from this.

Sure thing! I don’t think that’s a personal question =)

I eat omnivore, mostly low-carb. No sweets at all. I also try to incorporate early time-restricted feeding and/or intermittent fasting on a semi-regular basis. It keeps me relatively stable.

I have tried keto, but I have never tried carnivore. No desire because what I’m doing works well for me and has similar effects (mitochondrial). I can’t tolerate vegetarian, because I’m very sensitive to FODMAPs. I believe these therapeutic diets should be short-term trials or used intermittently as needed. They’re very hard to adhere to, especially if you love food and the social aspects of food.

I’m also lactose intolerant. When I was a student, I actually tested myself for the gene. However, I have some tolerance to lactose now that my gut health has improved. As you mentioned here, better enzyme production, even if it’s limited. I’m genetically lactose intolerant but phenotypically tolerant and can handle most lactose sources.

Carnivore made a huge difference for me. The IBS and gut pain that troubled me since I was a little kid were gone. Lost 20 lbs of inflammation. I was able to do light exercise again and build some muscle. Only issue is that I kept losing weight. I had to add back some bread and it stopped the weight loss. Still can’t deal with vegetable fiber. Causes tons of gas and gut pain. Probiotics have been useless for building back the gut flora to digest fiber. The bread causes inflammation problems, but I don’t have any other alternatives. That’s just where I’m at now. I’m sure that this isn’t for everyone and it takes all the fun out of eating, but if you’re desperate, you might give it a shot. It definitely didn’t hurt me. Blood tests numbers are perfect.

If running into problems with bread, there is some evidence, including anecdotal, that sourdough bread causes less problems in some people. If you are eating bread it might be worth a try.

Thank you Alex. I’ll try that.

Will you try adding one vegetable at a time back to your diet? as most will actually be good for you, and would be really good to know which ones aren’t a problem and which that are. You are in an ideal place now to know. Start one t a time with the FODMAPS ones first. I’d be interested to hear your progress if you answer back here months in the future it will still email me. Thanks

Points I agree and disagree on, plus several side comments.

For the record, I am on a higher protein keto diet, with carb foods selected primarily for their polyphenol content. I want to especially point out quality extra virgin olive oil (but 80% globally is adulterated, so buy local or from trusted producers), unsweetened cranberry, and green tea. I also like parsley for high apigenin content. So we are in general agreement. I have a background in biochemistry, so I am interested in these things.

As an ME patient I reversed my type 2 diabetes in three months on a ketogenic diet. Type 2 diabetes is now reversible, in new patients, at 87%. However this best diet is not suitable for ME because it involves rigorous exercise.

I have also been doing resistance training for six months now, with modest results. This is due to the Perikles protocol, my name not a formal name, where we do not get out of breath and only do resistance training for a maximum of thirty seconds, with long rests and no repeats on the same muscle groups on the same day.

I want to make a special shout out to the green keto Mediterranean diet. It is especially good for most people, but again not tested on ME or CFS patients.

The big one I disagree on is butyrate. If ketogenic, or eating animal fat or butter, then you don’t need much butyrate production from gut bacteria, because these supply butyrate. The caveat here is that any dietary approach for us has to be tested on the ME and CFS populations, and at the individual level we can vary too.

I was aware of how to beat salicylate sensitivity, according to the science, for two and a half decades. I did not do it. Now I am consuming at least a teaspoon of butter a day, which is also high in butyrate, I get enough arachidonic acid to allow me to eat a high polyphenol diet, though sometimes I need more butter. Salicylates are simple phenolic compounds, and there is a tendency to be higher in high polyphenol foods.

Now the science shows that older people can benefit from as much as 2.4g of protein per kilo of body weight, and the amount of protein most can absorb and use well, in one meal, is something over 100g. We don’t have a better figure because the study never thought we could use that much and never tested it. Younger people do not show much benefit from protein at over 1.6g/kg.

I also think ME patients need more protein, because we use amino acids to replenish citric acid cycle intermediates. This needs empirical testing.

Lastly any major change in foods, especially macronutrient profiles, should be slow. Allow two months. Rapid change stresses the microbiome, and sometimes general physiology. Big changes take time.

Absolutely right! Patients do need more protein than a healthy person because we seem to use salvage pathways. Protein requirements also increase with age–a very important factor to avoid sarcopenia.

Vitamin C is abundant in many meats, especially goat meat. There are two compounding issues. Cooking destroys a lot of it, and lower carb intake decreases the need for vitamin C.

Most college classes teach that there is no vitamin C storage. This is false. There is no specific tissue that stores vitamin C, like the liver for example. EVERY cell holds onto vitamin C because it quickly dies without it. A typical person has about a years supply. I do eat the occasional raw vegetable or low carb fruit to be sure I get enough, but a lifetime on just meat does not seem to harm native tribes at all. This includes Inuits and Maasai tribes.

On CVD risk and saturated fat, two saturated fats are likely to be beneficial, stearic acid and pentadecanoic acid. More is better within moderation.

The real issue is that a high carb diet with lots of saturated fat creates problems. The absolute worst food I am aware of is the French fry if cooked in something like tallow or most vegetable oils, and even worse if not consuming protein or fiber. Air fry potato is my suggestion.

There are subgroups of patients with cardiovascular disease. Some have no problems with high LDL-C, some have moderate CVD risk. High blood glucose (and I argue fructose which we do not routinely measure) glycate LDL, so the real problem is the sugar. Oxidative stress, including inflammatory stress, cause even more damage to LDL. Genetic issues with LDL removal also mean its out there longer, taking more damage. There is no question that damaged LDL is a big issue, leading to foam cell production.

This is an excellent article. Dr. Craig’s explanations offer a number of meaningful insights.

For readers looking for a wider perspective, TLC for Mitochondria is a post where I go a little deeper on supplements and lifestyle. It’s freely available here:

https://longcovidjourney2wellness.substack.com/p/long-covid-tlc-for-mitochondria

I prefer to boost with plant proteins instead to avoid endotoxins entering my blood that trigger IL-6 and TNF-a (and not just from the bacteria that live off animal fat and protein in the gut) but also the endotoxins that are already in meat. Which causes inflammatory spikes within hours of consumption. Plenty of studies now show that. Links within the links below.

Note: don’t shot the messenger, these are good citations to good studies that have since been repeated

‘How Does Meat Cause Inflammation? – NutritionFacts. org’

https://nutritionfacts.org/blog/why-meat-causes-inflammation/#:~:text=We've%20known%20for%2014,Why%20Animal%20Products%20Cause%20Inflammation).

Also explained here in short video format with citations to studies

“The Leaky Gut Theory of Why Animal Products Cause Inflammation”

https://nutritionfacts.org/video/the-leaky-gut-theory-of-why-animal-products-cause-inflammation/

‘The Exogenous Endotoxin Theory’

https://nutritionfacts.org/video/the-exogenous-endotoxin-theory/

From my understanding, a carnivore diet is low in butyrate but it doesn’t matter as you will instead produce a lot of ‘iso-butyrate’ (butyrate equivalent) from the meat protein you eat. So the body has a work around.

I have experimented with carnivore in the past for extended periods and I feel significantly better with improved stamina and reduced PEM.

After about six months on it, I tested my vitamin C and it was very good. There is actually some vitamin C in muscle meat (it is often listed as zero but this is because they never bothered to test it back in the day, it was just assumed and became dogma). I also read some research but can’t remember the details that the body has another process by which to avoid scurvy when in a high fat ketogenic state.

The transition can be rough and does need to be managed carefully.

My main mistake with carnivore initially was not eating enough fat. I later decided to ask a butcher to prepare ground beef at 30% fat and that gave me enough energy.

Thanks for the comment. It’s a very important point; I should have added it to the original post. =)

You’re right that isobutyrate can be produced on a carnivore diet via fermentation of branched-chain amino acids like valine. But from a gut health perspective, what matters isn’t just the SCFAs themselves—it’s the microbial communities responsible for producing them.

Butyrate is usually made by fiber-fermenting species like Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and Roseburia, which support gut barrier integrity, regulate immune responses, and have anti-inflammatory effects (Louis & Flint, 2017). These beneficial microbes are often reduced in ME/CFS (Frémont, 2013), and they rely on fermentable fibers, not animal protein, for fuel.

In contrast, isobutyrate is primarily produced by proteolytic bacteria breaking down amino acids. While it’s not inherently harmful, these bacteria also tend to produce other metabolites like ammonia and p-cresol that can be proinflammatory and disruptive to the gut barrier over time (Windey, 2012). Diets high in protein and fat (and low in fiber) tend to favor bacteria that thrive in harsher, more acidic gut conditions created by bile. These species are often linked to inflammation and reduced microbial diversity. (David, 2014).

It’s also true that grass-fed butter and ghee provide dietary butyrate (primarily in the form of tributyrin), but most of it is absorbed in the small intestine and may not reach the colon, where butyrate has its strongest impact on gut health. So while helpful, this isn’t a replacement for colonic fermentation by a diverse fiber-fed microbiota.

So even if SCFA levels go up on carnivore, the loss of microbial diversity and shift in community structure could matter more, especially for a patient population that already tends to show signs of dysbiosis.

That said, individual symptom relief is always important, and your experience with better energy and reduced PEM deserves attention. I just think we should also be mindful of how different diets shape the microbiome in the long term, beyond what metabolite levels alone can tell us.

Louis, P., & Flint, H.J. (2017). Formation of propionate and butyrate by the human colonic microbiota. Environmental Microbiology, 19(1), 29–41.

Windey, K., De Preter, V., & Verbeke, K. (2012). Relevance of protein fermentation to gut health. Molecular Nutrition & Food Research, 56(1), 184–196.

David, L.A., et al. (2014). Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature, 505, 559–563.

Frémont, M., et al. (2013). High-throughput 16S rRNA gene sequencing reveals alterations of intestinal microbiota in ME/CFS patients. Anaerobe, 22, 50–56.

Thank you Courtney for your thoughtful and interesting response.

I’ve listened to a lot of carnivore doctors and they would suggest that the gut microbiome simply adapts to reflect what we eat. So if we eat a more omnivorous diet, then our microbiome will reflect that. If carnivore, we will develop the kind of microbiome that reflects that. It will be, therefore, just as it needs to be for the dietary context.

Ideally, we would have studies on a carnivore microbiome specifically, considered in the context of that diet, but we don’t. So these things remain speculative.

However, some people do thrive on carnivorous diets for decades. As have – and do – some tribal peoples. This suggests that the ways the microbiome shifts on a carnivore diet might be supportive of health.

There are also well respected studies that relate your blood type, to your diet. Depending where our ancestors came from and what diet they were exposed to!

There are so many potential factors affecting the best diet, that in reality, we should trial them individually and go with what works best for our health.

Diet is very personal. There are so many factors involved. Many ME patients feel better when they eat meat, and I’m not talking about excessive consumption. Plant-based diets contain a lot of pesticides, which is also bad. In addition, meat can also be processed with preservatives. Although I am convinced that an individual diet is an important factor in our disease, you cannot say that a carnivore diet is bad. All these references to studies mean nothing until there is an RCT in which one group of ME patients follows a carnivore diet and the other group follows a plant-based diet. As far as I know, this has not been done yet. Then food intolerances and the intestines also play a role. But there is certainly an important problem in the gut. So it remains speculative! Like so many blogs I have read here lately.

N=1 with the usual caveats from that. i was lacto vegetarian for a year or so in about 1993 to try to treat my ME, and tried a plant based high omega 3 diet to boot. My health declined and declined. One day I was out, busy, in PEM, and needed to eat. I ate a meat pie, which is a highly processed food. Within hours I felt fantastic! That was the last day I was lacto vegetarian.

Generally speaking humans can eat anything from full vegan to full carnivore, and many variations in between. Vegan does however require very close attention to nutrient deficiencies particularly after 4 years. The biggest carnivore shortfall I can see, and its often the case with vegan though there are alternatives there, is lack of iodine. Simply eating seafood from time to time will help there. With vegan the alternative is seaweed.

Just because people can eat almost anything does not mean its optimal for specific medical conditions like ME or CFS, though we have much more to learn about what we often need.

I am a perfect candidate for carnivore, being salicylate sensitive. Yet I am ketovore, protein centric keto, because arachidonic acid in animal fat sources bypass the long chain omega 6 fatty acid deficiency induced by most plants containing salicylates. I should be on krill oil, to replace long chain omega 3, but I have not started that yet. Krill oil more readily crosses the blood brain barrier compared to regular oil, which fails to be absorbed by the brain unless its properly processed, by phosphorylation if I recall correctly.

Finding the right diet for an individual is a journey. We are very fortunate if we find any standard diet to be optimal for ME, I am not sure that is common. We need more research (my mantra).

I tried carnivore diet almost 10 years ago now, my dr suggested a trial of ketogenic diet for mitochondria boost and I don’t tolerate dairy or eggs. Within 5 days of eating only beef, I was in the ER with metabolic acidosis. Apparently this isn’t supposed to be possible but it happened to me. 3 days in the ICU and a varied diet with carbs and I was on the mend.

Really interesting article, thanks Dr Craig.

Here’s my own experience…

I switched from the standard western diet to keto in April 2014 (meat, fish, eggs, non-starchy veg; I excluded: grains, dairy, processed foods, alcohol) and saw immediate and significant improvement. Within 48 hours, my chronic headaches and migraines had gone and my long-standing (presumed) duodenitis also completely resolved. I presumed, due to the rapid elimination of these symptoms, that they were most likely the result of a gluten (lectin) elimination, but can’t be sure as I’ve never done a re-introduction test.

Although I saw some weight loss on keto (my BMI dropped from 24 to 21) it didn’t improve my overall ME symptoms, and I also continued with some mild IBS-type symptoms (e.g. bloating).

Therefore, as I thought there was still room for improvement, I started carnivore in September 2022. I have to admit, the transition to zero-carb was pretty brutal (2 days of significant withdrawal symptoms incuding agitation etc., and 3 weeks of visual migraines) but that then resolved. And all my residual gut symptoms resolved too! What I also noticed was that my skin (mainly rosacea) also resolved on carnivore. After later re-introducing some dairy (butter only) and whole eggs, which led to my skin flaring up again, I concluded I was intolerant of both dairy and egg whites.

So I can honestly say that the best I’ve felt is on carnivore. I eat mainly beef, and also some pork, duck, lamb’s liver and ox heart (the organ meats are supposedly very nutrient-dense, esp B vits), fish (wild salmon and some cod/haddock), seafood (mainly prawns, some scallops, oysters) and egg yolks, with extra organic pork or beef fat. I very occasionally add back small amounts of non-starchy veg (cabbage, broccoli, cauliflower), but only every 6-8 weeks or so, and thankfully my gut bloating has not returned when I do so. I also supplement with minerals (Dr Myhill’s multi-mineral mix).

The only potential downside to carnivore is that my ketone levels are not as high as they were on standard keto (although are still in the therapeutic range) due to the higher protein levels when eating mainly meat. However, I also do 4x 24-hour fasts per week which boosts my ketone levels and, on carnivore, I find these fasts easy to do (and the reduced amount of exertion spent on cooking is also a definite bonus!).

The main issues, as you raise, are the possible long-term negative consequences of carnivore, and the lack of robust research into this area is certainly frustrating. However, I found Dr Saladino’s book “The Carnivore Code” to be particularly helpful, including the references he cites, with regard to understanding cardiovascular risk, human’s need for fibre etc. and I’d recommend this to anyone whose interested in carnivore. (Of note, Dr Saladino himself is actually no longer fully carnivore, but adds in raw milk and some fruits and honey as he says this works best for him!). Ultimately, however, I’ll carefully monitor my medical test parameters over the coming years, including at some point doing a lipid subfractionation assay and CTA, to formally assess my cardiovascular health. Saying that, I’m convinced that the main risk to CVS health is excessive carb intake and junk food, not saturated fat.

Overall, changing my diet (keto or carnivore) has not directly affected my ME symptoms, unfortunately. But it has had a dramatic effect on my co-morbidities and so made life just a little bit easier and so, from my perspective, has definitely been worth doing and I’ll certainly stick with it. 11 years into keto / carnivore, it’s now just a way of life to me. And, of note, family and friends who have also tried keto / carnivore have all seen significant, and sometimes life-changing, health improvements with a variety of illnesses and ailments.

Thanks so much, Dr Craig, for your blog on this important topic.

The CDC monitors hundreds of toxic chemicals and heavy metals in the body. Don’t take my word for it, read about this tracking program.

https://www.cdc.gov/environmental-health-tracking/php/data-research/biomonitoring-population-exposures.html

What does that mean for you? If you go on “any” extreme diet and start releasing these chemicals from fat stores in the body into the blood stream, you may get much sicker.

We don’t have a good way to remove toxic chemicals from our bodies without having them recirculate to important places like the brain, kidneys, heart, etc.

I once talked with the medical officer at Redstone Arsenal, a government installation. Somehow, they had lost 100 pounds of mercury into the surrounding environment and people working at the arsenal were exposed.

He told me you had to be very, very careful with any mercury detox program, because once it was released from fat stores, it could settle in your brain (the Mad Hatter in Alice in Wonderland), your kidneys or even your heart (I know of one famous doctor this happened to).

The sickest I have ever been in 40 years of ME/CFS was when I went on an extreme allergy diet. I lost a lot of weight very rapidly and got very ill.

On to the Keto Diet. This diet was developed by John Hopkins to treat children with extreme seizure disorders that could not be controlled by medication.

The diet has to be started in a hospital setting and carefully monitored.

It is not a diet recommended for the general public to lose weight.

How this became a popular diet in the mainstream is beyond me?

For 20 years, I served as the co-chair of the Public Interest Partners of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. Partners represent national patient health organizations where toxins are believed to play a part in the conditions represented by the groups (cancer, lung disease, birth defects, learning disabilities, autism, autoimmune disorders, endometriosis, etc.)

We won’t get closer to answers for ME/CFS and even Long Covid until scientists study the environment these patients have been exposed to since birth.

Thank you for reminding/ educating people about this! Detoxing is possible but needs to be done slowly and correctly (hopefully under a Dr-Naturopath) BEFORE starting any extreme diet or weight loss program. This has been mentioned above as well by people who have experienced detoxing gone wrong.. I like to tell people, as an example, that part of the reason they feel so bad after a case of the flu or a stomach “bug”, where they can’t eat without vomiting for a few days, isn’t just the “bug” which was killed off by the body pretty quickly but the dumping of toxins from the liver, etc. because of the unintentional fasting. Once again the motto, “Go Low and Slow” pertains! Thanks.

1. All things in moderation.

2. The fact that “meatfluencers” is a thing is such a huge red flag.

I try to stay away from processed foods as much as I can – but low energy does impact how much cooking I can manage. Whole foods, lots of variety. Personally extremes don’t work for me.

https://nutrigardens.com/blogs/blog/is-nitric-oxide-good-for-you-doctors-share-the-truth-on-how-nitric-oxide-works?srsltid=AfmBOoqZSfU5rNtsXmv68G5DdRktBeAD6YsFz-1fxInWR4pPw5ZvonDZ&fbclid=IwZXh0bgNhZW0CMTEAAR7A2m_Gz9-JTkUin-wD1i1cYTb6xti3KmaFZUruvzwY0yUe6ApJR79xStnxlA_aem_RAlmzhuQJiM5YlnKcwJ-_g

Courtney

What do you think of a Nitric Oxide diet?

I’m not familiar with that one, Wallace.

Anti-inflammatory diet works best for me. See Dr. Goldner’s work online. Used together with fasting to kickstart improved autophagy. I’ve relaxed a bit after almost two years of strict adherence, as I’m slowly getting better.

I tried keto diet in the beginning (Dr. Myhill), but it didn’t make much difference even after 6 months.

Right on! This is exactly what I do and advocate for, too. It’s the most sustainable way. My Basics course walks you through exactly how to do an anti-inflammatory diet for those who might not know.

Dr Craig,

Excellent and well informative article! 🙏

“Ervaringsdeskundige”- lived experience. 🔑

As someone who suffers from CFS (Holmes criteria) + Fibromyalgia (Wolfe criteria), I have focused on nutrition for many years in an attempt to solve my own chronic disease puzzle. 🧩

Every patient is different and there exists hundreds of different variables that can help or worsen symptoms. 🧬

For me, personally, I have found that a carnivore diet coupled with intermittent fasting (18/6) and amino acid therapy (Gersten protocol), has been very beneficial in treating my inflammation, gut dysfunction, and fatigue (mitochondrial energy deficiency).

My doctors can see huge changes in C-Reactive Protein and Sed Rate levels and also changes in WBC levels during my quarterly biomarker checkups.

Protein intake improves my QOL immensely- physically and mentally.

L-Carnitine improves energy for me and lessens pain.

GABA relaxes me.

B12 improves my energy.

Vit C helps with chronic pain and immunity.

L-Tryptophan helps my mood.

L-Tyrosine and DLPA- in moderation- improves my energy too. 👍

NAC improves my breathing. 🫁

Processed foods and carbohydrates (even the good ones) augment my lethargy and increase my pain levels so I minimize their intake.

Fermented products such as kimchi and Greek yogurt help with regulating my gut microbiome.

Some vegetables help with L-Arginine intake and asparagus + beets seem to help regulate my circulatory system.

Dark chocolate 🍫 improves my low dopamine- in moderation.

The problem is that I crave sugar (soda + cookies 🍪 and pasta 🍝) at times and it is difficult for me to stick to a disciplined nutritional regimen. 😞

Thanks again for all the information ℹ️ you provide! 🦾

All the best to my Brothers + Sisters out there trying to improve their quality of life. ❤️

And thank you Cort for providing this forum for all of us to help find knowledge, strength, and courage to get through all the days and nights. 🙏

Wow! I think that’s one of the best diet related posts I’ve ever read online! Totally non-judgemental, no scare tactics, no bias, just facts. No drugs, no supplements, just real food. I had to go back and look at her training and, no surprise, much of it wasn’t in the US. My mother was a registered dietician and I have a background in animal nutrition. My dog lived for 4 years after a cancer diagnosis on a homemade ketogenic plus having Lyme, CFS and MCAS myself, I’ve been heavily into diets and nutrition the last 10 years.

I must admit I saw the headline and thought, oh no. I didn’t want to spend hours debunking info and explaining the facts to people with questions. This really made my day! I may have to check out her info on MCAS as it’s always a struggle. 🙂 Thank you!

And thank you for the nice comment. This made my day =)