Long-COVID exercise study brings it closer to ME/CFS – and suggests a wholesale shift in muscle production may have occurred.

Reportedly the top respiratory hospital in the nation, doctors at the Post COVID Center at National Jewish Health quickly began giving long-COVID patients exercise tests.

People with long COVID will appreciate this study’s attempt to get at perhaps the core problem in the condition – energy production. People with chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), on the other hand, will appreciate seeing new researchers focusing on an area of great interest to them.

This study, “Decreased Fatty Acid Oxidation and Altered Lactate Production during Exercise in Patients with Post-acute COVID-19 Syndrome“, brings in a cadre of researchers from the Pulmonary Physiology Lab at the University of Colorado Anschutz medical campus, and, get this, the Center for Post COVID Care at National Jewish Health Hospital, in Denver. National Jewish Health, by the way, calls itself “the leading respiratory hospital in the nation and the only one devoted fully to the treatment of respiratory and related illnesses”.

The Center and the eight doctors associated with it glommed onto the exercise issues in long COVID early and started sending people with long COVID to the exercise lab in June 2020.

Study Results

This was a retrospective study; i.e. the data came from chart reviews of cardiopulmonary exercise (CPET) tests done from June 2020 to April 2021 on 50 people with long COVID. During the test, the participants exercised to exhaustion (or near) on a bicycle.

It was probably an evolutionary necessity that our bodies retain an ability – even when sick – to produce substantial amounts of energy for short periods of time when needed. Some people with ME/CFS retain their ability to do that while others don’t. This study suggests the same scenario plays out in long COVID – some people can produce normal amounts of energy on a one-time basis while others can’t.

VO2 max – which measures the amount of energy one is able to produce during one’s maximum effort – was normal in 68% of the participants but reduced in almost a third of the participants (32%). Peak VO2 – the absolute peak energy produced at one point during the test – findings were similar. Given that about a third of the long-COVID patients generated unusually low amounts of energy, one wonders how many more would have had trouble doing so in a two-day exercise study.

Then it got really interesting. As we’ve seen in ME/CFS, the long-COVID patients’ levels of lactate – a byproduct of anaerobic energy production – were increased. That suggested that the people with long COVID were rapidly blowing through their stores of clean energy produced by aerobic metabolism. We use aerobic metabolism in the mitochondria to produce most of our energy. It’s particularly needed when we do things like walk, run, or bike.

A more primitive form of energy production (think lizards), anaerobic energy production is good for quick bursts of energy but quickly poops out when stressed. It’s not designed to carry the load required for even a 10-minute exercise test.

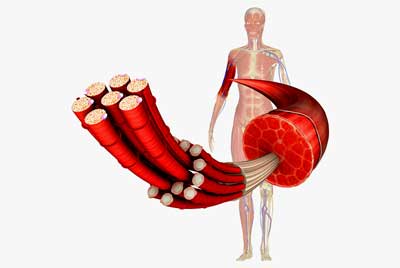

Could a mitochondrial dysfunction have changed the types of muscles found in long COVID and ME/CFS?

When the aerobic energy system is overwhelmed, the anaerobic energy production system steps in to give us a last boost of energy. That comes at a price, though. Less energy is produced, and substances like lactate build up and produce pain, fatigue, etc. That last extra pop, though, might have given our ancestors enough energy to escape from the cave bears, dire wolves, or saber-tooth tigers they were running away from.

The increased levels of lactate found indicated that the long-COVID patients relied more on anaerobic energy production than expected.

In contrast to the third or so of long-COVID patients who failed to reach normal levels of energy production, the authors reported all 50 of the long-COVID participants produced significantly lower levels of fatty acid oxidation. That meant that a key source of the electrons needed to produce energy in the mitochondria was impaired.

This suggested that, when put to the test, the people with long COVID were unable to produce normal amounts of energy from the breakdown of fatty acids. This fits well with the results of recent ME/CFS studies which suggest that something strange is going on with “fatty acid oxidation”; i.e. the breakdown of fatty acids to provide energy substrates for the mitochondria.

Mitochondrial Dysfunction Pegged

The authors then plunged into an illuminating explanation. The anaerobic energy gets a bad name in ME/CFS, but it’s actually operating much of the time – at low levels. It’s only when we rely on it for things it’s not designed to do that we start experiencing pain and fatigue. Lizards, after all, don’t jog.

The Gist

- Early in the coronavirus pandemic, The Center for Post COVID Care at National Jewish Health in Denver began having its long-COVID patients do maximal exercise tests.

- This retrospective study of 50 people with long COVID did not find reduced exercise capacity (VO2 max, peak VO2) overall but did find reductions in exercise capacity in about a third of the participants. (Two-day exercise tests pick up more evidence of reduced exercise capacity in ME/CFS.)

- Increased levels of lactate early in the exercise test, however, suggested that the anaerobic energy production system kicked in early. The anaerobic energy production system produces less energy than the aerobic energy production system – and produced substances like lactate which, when they build up, produce symptoms like pain and fatigue.

- All the participants also showed evidence of impaired use of fatty acids to provide substrates for the mitochondria. That was an interesting finding, indeed, given several recent ME/CFS studies implicating fatty acid metabolism in ME/CFS.

- The authors suggested the increased lactate levels early in the exercise period might result from a switch in the production of muscle fibers from slow-twitch muscle fibers to fast-twitch muscle fibers.

- Slow-twitch muscle fibers – which we use for things like walking – use aerobic metabolism to produce energy. Fast-twitch muscle fibers – which we use for short bursts of energy like weight lifting – use anaerobic metabolism.

- A switch from slow to fast-twitch muscle fibers, then, could result in an increased emphasis on anaerobic energy production. Plus, because slow-twitch muscle fibers also use lactate to power aerobic energy production, increased levels of lactate could reflect a switch from slow-twitch to high-twitch muscle fiber production.

- Back in 2009, an Italian research group found increased levels of fast-twitch muscle fibers in ME/CFS. Nine years later, they proposed that the muscle fibers in ME/CFS were aging rapidly and that the muscle fiber switch was likely due to mitochondrial dysfunction.

- This study findings could suggest – as past findings have – that very short bursts of intense exercise might work better in ME/CFS and long COVID.

The authors noted that at these lower levels of exercise, the lactate we produce should be oxidized to provide fuel for the mitochondria found mostly in the slow-twitch muscle fibers; in other words, it should not build up. That suggested that this slow-twitch muscle fiber lactate uptake process may not be functioning well in people with long COVID.

We use slow-twitch muscle fibers for more low-intensity activities that require endurance such as walking running, and swimming. Fast-twitch fibers are made for more high-intensity activities such as lifting weights. They also jump in to provide support when slow-twitch muscles become fatigued.

Twitchy Muscle Fibers in ME/CFS

The possibility of a muscle fiber switch in ME/CFS has been raised by David Systrom and Mark Van Ness more recently, but an Italian research group has led the way.

While the authors of the long-COVID paper didn’t mention it (they didn’t mention ME/CFS at all), back in 2009, an ME/CFS study found an increased incidence of fast-twitch muscle fibers. The authors suggested an “increase in the more fatigue-prone, energetically expensive fast fibre type… might contribute to the early onset of fatigue typical of the skeletal muscles of CFS patients“.

Indeed, the slow-twitch muscle fibers found in low supply in ME/CFS patients’ muscles, largely rely on aerobic energy production, but the fast-twitch fibers that predominated rely more on glycolysis; i.e. anaerobic energy production. The groups’ gene expression results also suggested that a shift towards more anaerobic energy production had occurred.

While this shift can occur as a result of low activity, the Italian group’s findings suggested this was not so in the case of ME/CFS. They also noted that this muscle fiber shift found puts a further strain on ATP production, which the body typically resolves by increasing glycolysis (anaerobic energy production), which further increases lactate; i.e. it can produce a vicious circle.

Old Muscles in ME/CFS?

They weren’t done with ME/CFS, though. Nine years later in “Old muscle in young body: an aphorism describing the Chronic Fatigue Syndrome“, they provided evidence suggesting that the muscles in people with ME/CFS were aging more rapidly than usual. They proposed that a mitochondrial dysfunction was producing large numbers of free radicals (reactive oxygen species) that were damaging the muscles. They even suggested that high levels of calcium (shades of Wirth/Scheibenbogen) in the muscles would lead to a chronic state of contracted muscles.

Another study reported that a group of ME/CFS patients with a severe infectious onset had the trifecta – high levels of free radicals even at rest, and, in what sounds like very old muscles indeed, their muscles were mostly dead to the world (didn’t respond to exercise).

Time will tell if critical parts of ME/CFS have been on display for all to see for quite a while.

Conclusions

The authors believed their study was the first to suggest mitochondrial dysfunction in long COVID.

It’s encouraging to see similar findings pop up in this most crucial of areas – energy production – in long COVID and ME/CFS. This retrospective study found normal exercise capacity overall (but reduced exercise capacity in a third of the long-COVID patients), but more importantly, perhaps, increased lactate levels early in the exercise process and reduced fatty acid oxidation, indicating that mitochondrial dysfunction was present and “metabolic reprogramming” had occurred.

The study pointed back to a possible issue in ME/CFS that achieved some prominence with an Italian research group but hasn’t been discussed much elsewhere: whether a switch to more anaerobic fast-twitch muscle fibers and away from more aerobic slow-twitch muscle fibers has occurred in these diseases. If this is so, the muscles simply may not have the capacity to produce much energy aerobically and could help explain why the people with ME/CFS and/or long COVID have so much trouble with exercise. It might also suggest that the best form of exercise for these conditions is very short, possibly intense bouts of weight-bearing exercise (???)

All of this may circle back to the main driver – a mitochondrial dysfunction – a distinct possibility not only in long COVID and ME/CFS but in fibromyalgia as well.

The study had a number of limitations: it was relatively small, was retrospective and it had no control group – so the results need to be validated in larger studies. Its results do appear to jive with what we see in ME/CFS however, and the authors stated they believe theirs is the first study to provide evidence of mitochondrial dysfunction in long COVID.

Health Rising’s Quickie Summer Donation Drive is On!

Health Rising’s Quickie Summer Donation Drive is On!

Thank you for this information, as someone who suffers from ME/CFS exercise leaves me bedbound. The more long covid is studied , the more insight we have into ME/CFS.

Agreed. I’m really very thankful and still kind of pinching myself as a long term person with ME/CFS who is used to things not going our way – at the way things are turning out – that the long COVID patients are looking so much like people with ME/CFS when stressed with exercise.

I was so glad to hear that David Systrom is communicating his invasive study results to the NIH RECOVER Initiative researchers. If we don’t see a big, big effort to dig into the exercise physiology of people with long COVID – an effort that also lays bare as much as possible what’s going on in ME/CFS – I will be shocked.

Cort, we are back to fatty acid biochemistry in ME/CFS. Every day I ponder the significance of Lipkin’s lab finding a low level of butyrate and other short chain producing fatty acid bacteria in the stool of ME//CFS patients. (I was Bacteriology grad student, when this disease derailed my career in Biology.) Do these bacteria provide some of the precursors that our mito’s need to metabolize/produce fatty acids? One lab “created” a fatigued mouse line (I can not find the paper.) They were able to transfer the fatigue symptoms to healthy mice via a fecal transplant.

‘Faecalibacterium prausnitzii’ is 5% of our gut biome. Lipkin’s Columbia grad students utilizing their shotgun metagenomics sequencing technique found ‘F. Prausnitzii’ and ‘Eubacterium rectale’ low in ME/CFS patient’s stool samples. The quality of the fecal samples were very reliable as they were provided by Susan Levine, L. Bateman, N. Klimas, J. Montoya, and Dr. Peterson’s Incline Village patients. Three other ME/CFS – Fibro labs have similar lab findings.

I believe it was Dr. Myhill who postulated that the mitochondria, which are bacteria we incorporated into our cells along with their own set of DNA, can transform into “battle status”. They forgo aerobic ATP production (oxidative phosphorylation) to protect themselves against bacteria, virons, and mycotoxins.

The mention of calcium in the post, reminds me of the very controversial Marshall Protocol. Marshall has always maintained that the vitamin D Nuclear Receptor transcribes over 900 genes. Some of that activity involves expression of antimicrobial peptides and calcium metabolism. Marshall believes that chronic bacterial infections interfere with the innate immune response by disrupting the Vitamin D Nuclear Receptor.

I found this paper particularly interesting I have cfs me fybromyalgia

I also now have long covid so you can imagine how much this has affected me…….

The only way I can manage my situation is to pace myself not easy.

I also had a spinal surgery 3 years ago at the time my grandson was studying to become Personal Trainer massage therapist he asked me to help him practice his skills (with someone older) hahaha!!?

So for approximately 3 years he’s been helping me to get mobile all I can manage is one hour a week 30 minutes exercise and 30 minutes massage and we have worked hard to EVENTUALLY find an exercise program for me that I can manage without being unable to do anything for 3 days after 😩

This is what I have found interesting in your article about short bursts of energy

In muscles 💪 We have found I can actually lift weights incredibly well and easier than longer sustained exercise bursts

This has only happened in the last couple of months it’s been an incredibly interesting long process to get to this…!!??

My journey continues !!!

Interesting, Lynda – someone just emailed to say they have a similar experience.

I have had long Covid since March 2020. I’ve had all sorts of symptoms that come and go – including extreme fatigue, post-exertional malaise, twitchy muscles, neuropathy, tinnitus, burning mouth syndrome, eye problems, gut issues and brain fog. I was never hospitalized with Covid, as I had a mild case with no respiratory issues.

I was diagnosed with Small Fiber Neuropathy. I also did a MITOswab test and the results showed that my mitochondrial respiratory chain complexes – RC-I activity was significantly below the normal range and my RC II+III activity was below the normal range. My doctor said she has seen similar results in some of her CFS/ME patients. She said some of her long covid patients have been seeing positive results with using Oxaloacetate and recommended that I try it. Oxaloacetate is part of the Krebs Cycle in the mitochondria.

I’ve tried so many different things over the last two years in attempt to recover from my post viral illness. This was really the first thing that has helped with my debilitating fatigue. I actually can go on walks, work in the yard, and clean my house again. It has been so wonderful to have energy again. I’ve got a long road back after being so physically limited for so long – but thankfully I’ve turned a corner.

I have heard there are some clinical trials underway involving Oxaloacetate and Long Covid. I thought I’d share myself experience for what it’s worth. I don’t completely understand it all – I’m just grateful to be feeling better since I I started taking Oxaloacetate back in March.

Glad you’re doing better and thanks for sharing your story. 🙂

Thank you so much for keeping us updated with the latest research Cort (and for providing The Gist boxes too!) Not only is it helpful and informative, but it helps keep me positive when I’m unable to do much myself – I’m sure many, many others feel the same!

Glad to hear it. You know it helps me as well. I think the next year is going to be so interesting….It just seems like things are lining up. Time will tell!

Where can I get Oxaloacetate?

I was diagnosed with CFS/Fibromyalgia in 1991.Mel’s story really hit home for me. I have all the symptoms he mentioned. The burning mouth has never been explained to this day. It just seems like a mystery when I mention it to physicians.

Will do more research on Oxaloacetate.

Thank you Cort.

I read from Anthony William (medicalmedium.com) that this could be as a result of inflamed cranial nerves, particularly the trigeminal nerves. Covid can unfortunately inflame the cranial nerves which could account for all these crazy symptoms we’ve been experiencing. Hope this helps.

That could cause a lot!

There is an important piece of information that I didn’t see when I read the paper. Had any of the 50 people studied been hospitalized during their acute infection? There are some references to ICU patients in the paper, but I didn’t see anything specific. For Long COVID, hospitalized vs. non-hospitalized is a key variable,

I didn’t find any references to what kind of long COVID patients these were, either. This study, interestingly was submitted in the form of a letter. It didn’t have quite all the data that a normal study would have; for instance, I believe some statistics were cited which did not appear in table form. I wonder if they wanted to get it out as quickly as possible.

In reading this and seeing the timeline of the study at NJ, I believe I was a part of it without knowing it. I was not hospitalized, performed the described test, was told my VO2 max was abnormal (putting me in the 30% group) and that it was due to mitochondrial disfunction. Sadly, outside of collecting data on me, they did nothing to address the issue. Instead, sent me a bill for thousands of dollars several months later. When I later tried to get additional help, I was told to go back to my PCP for assistance. NJ may be a great resource for many, a “leader” even, but they were a huge disappointment for me. The only things I got from them was proof there was something wrong physically and, unfortunately, after the test, I had a huge setback, forcing me to go on FMLA and eventually, quit my job. It’s been 3 years since the onset, I am MUCH better, but still not back to my pre-Covid/vax status. What’s helped are treatments functional med docs have prescribed.

Unless you should have been hospitalised but weren’t. As was the case for some children who were very poorly in the first wave and remain unwell still. I’m sure there will be others who, for whatever reason, could not access hospital care and so for whom those categories don’t necessarily hold meaning.

This caught my attention as my son, a long term CFS sufferer has recently tried and succeeded in reversing his diabetes II by undertaking a strict Keto diet. As part of it he has been able to walk much further, lessen his restless legs problem, but has described that despite exercise he does not experience any reaction in his muscles ie he expects them to hurt but they don’t. He thinks they are starting to respond but its early days. He has always experienced lactic acid build up in his legs upon slight exercise and this also has lessened. He has been very disciplined with the Keto diet, eats only once a day and has experienced much improvement as a result. It will be interesting to see where this research takes us.

Your article led me to a finding that helps explain why when I try to contract my arm muscles, the contractions are jerky instead of fluid like they used to be.

“ If all of the motor units fired simultaneously the entire muscle would quickly contract and relax, producing a very jerky movement. ”

From:

“SKELETAL MUSCLE: WHOLE MUSCLE PHYSIOLOGY

MOTOR UNITS“

Found at website:

https://content.byui.edu/file/a236934c-3c60-4fe9-90aa-d343b3e3a640/1/module7/readings/muscle_twitches.html

It’s all got to be related, and I am encouraged the Italian Research Group researchers are continuing their close look at muscles.

I have this same jerky movement. Just went to NIH 2 weeks ago and their testing to try and define it has them baffled. Said I am n=1. I know that cannot be the case. Mine started 2-3 weeks after the 2nd Pfizer shot. ( I am a physician and have been trying to figure this like you). So glad to see this reference!!!!!!! I’d like to get a collection of videos from patients who have had this happen and send to them. Would you be interested in helping with this??

Did you get any answers?

This article rang a bell with me. Years ago I had some extensive testing done that found significantly lower levels of amino acids in my blood than average. This perplexed me as I (always) was a heavy meat eater. Now I am wondering, if my gut successfully broke down the ample protein I had ingested into amino acids, and if my cells were not utilizing/burning the amino acids for energy (as this researcher suggests), would that not increase (rather than decrease) the (unused) amino acids in my blood? I also wonder if it might be possible that if/when cells that are not using amino acids for fuel, may not use them because they are not available (if the gut does not efficiently break down proteins into amino acids)? Please forgive my pondering speculations. TY (again) Cort, for the excellent synopsis, and reconciliation with other research.

Dave, your experience with dietary protein not reflected in amino acid testing mirrors mine. It’s something I’ve always wondered about. The findings in the research this article describes resonate strongly with my experience.

This seems similar to my brain functioning. I can now process a certain level of complicated information fairly well, for a short time (20 mins or so), if I’m feeling rested. However, I often end up trying to squeeze the last bits of energy out of my brain, which means I’m much slower, it’s much more difficult and if I keep going it’s like my brain runs aground, like a boat getting stuck in sediment.

I was also reminded of Jarred Younger PhD’s work, where I think he found higher levels of lactate in the brain? So, I can experience my brain running well and efficiently at intense levels for a short while. My brain can run for longer and be fine now, if I’m more relaxed and not demanding so much processing.

Younger’s work itself is a replication of previous work by Natelson and Shungu et al. on brain lactate. He also replicated the earlier findings of excessive free choline in parts of the brain, a sign of excessive cell turnover due to inflammation/infection.

Maybe this is unrelated to the contents of this article, but one of my symptoms (particularly when nervous system is in a state of overstimulation) are very fast (and big) muscle twitches that involve movement of many muscles at ones.

It may be just a release of tension though.

JR I also have this…it’s always at rest. There are times when upon laying down and letting the muscles relax, I literally jerk like I’m having a sudden convulsion. It’s a horrible feeling. Cannot control it. It has something to do with the release/relaxing of the muscles and then bang it suddenly comes and for one awful moment the entire body jerks.

Another thing that caught my attention was the mention of the build up of calcium. When I first became ill years ago, I went to every doctor and had every test done I could afford and get to. There were only a few that came up with anything…one was that I had calcium ‘inside’ my cells. Where it should not be.

The other test that came back repeatedly positive was the test for Myasthenia Gravis (acetylcholine antibody receptor blood test) although I do not exhibit the features of Myasthenia Gravis. But it’s interesting that Myasthenia Gravis is a degeneration muscle disease.

Karin, among other muscle symptoms, I too experience that whole body jerk at times when lying down. I’m curious now about how many more of us would test positive on the acetylcholine antibody receptor test.

Karin and Pamela, thanks for your replies! My “convulsions” happen either at rest, or at times of high nervous tension e.g. sensory overload.

I’ll take note of your mention of acetylcholine antibody receptor test!

May I ask you how to test calcium in cells, e.g. what is the name of that lab parameter? (In case you’re Germany based, I am too.)

About your cells building up calcium, this is interesting because I think it may correspond to the Wirth & Scheibenbogen 2021 hypothesis on cell calcium overload as a consequence of adrenergic receptor autoimmunity, which I believe may in turn connect to Ron Davis’ nanoneedle experiments….

P.S. I do appreciate the “Gist” summary, as I am often to unwell to digest the full article!

When I’m tired I have trouble digesting the blogs (lol).

Thanks Cort – FYI I’m off to a clinic this afternoon with my 16 year old son for treatment to prevent ME ! As it plagues others in our family and I want to ensure we do everything we can to stop him getting it. Like many the details above ring true with me – can lift heavy weights for 20 minutes but struggle with walking for 20 minutes. I know there are many worse than I and some similar in that I can exercise but my body doesn’t recover and 48 hours later the herpes/glandular fever kicks in for 14 days. I’m not sure how this aspect fits into the scientific study but know someone on here will. Thanks again

Researchers have come to some conclusions about Gulf War Syndrome. The conclusion was that SARIN gas was the cause of the illness, but some people were genetically predisposed and more sensitive to the impact of the gas. It still does not explain the details of what is happening in the body to set off the process. https://www.dailymail.co.uk/health/article-10805419/Solved-Gulf-War-syndrome-mystery-Gov-funded-scientists-blame-SARIN-released-air.html

Hi Matt, I’m interested that your son is getting treatment to prevent ME. Certainly something that would interest others who have a family history of ME!

Can you give us an idea of what sort of treatment this is? Thanks very much.

You’re repeating a common misconception/error; lactate does not cause pain or fatigue in muscles.

Mitochondria rely on iron to function and many long COVID sufferers have been found to be low in iron. Could iron play a part?

So many studies pointing to mitochondria, it must be a key factor???

Hi,

In a different realm of ‘twitchy muscles’, I wonder if anyone regularly experiences them? This has been a longstanding symptom for me— most apparent in my legs. Would appreciate learning if others likewise have these, and any pearls is wisdom about their cause (or mitigation) gratefully accepted!

My symptoms are worst in my legs, and I’ve tried to research why muscles may be chronically contracted as my lower legs are. This research seems to indicate a possible reason. My nerve pain is always in my lower legs, rarely in my arms. I don’t know if its just because legs are used a lot more in every day life tasks than other body parts.

I am also curious if others with CFS have the worst pain, fatigue etc.. in the legs.

Hi Jessica! I hope you come back and read this:

You mention tight lower legs specifically… did you know the achilles tendon reflex was used to diagnose hypothyroidism?

Broda Barnes has a good book on the subject

I assume you’ve already looked into “restlegs legs syndrome” (RLS)? It seems it can involve twitches and spasms. Don’t know much about it, but there might be treatment options to research. I do have some tension in hands/wrists and legs and find leg massages and specific stretches before sleep beneficial. Some try magnesia I think. For me, worst pain is not in my legs.

Pain in feet also rings a bell with neuropathies such as small fiber neuropathies. But pls take my comment with a pinch of salt because I don’t know much about both and suppose there might a be many explanations.

I can relate to the disclosures regarding “convulsions”, spasms or myoclonic jerks. In fact, I began having epileptic seizures at age 15 (always preceded by myoclonic jerks). This was much later diagnosed as “atypical” Juvenile Myoclonic Epilepsy (JME). (?). However, my case of JME was extremely unusual in that I only had seizures within minutes after awakening after insufficient sleep, and that my seizures were (thereby) sometimes years apart (without medication). I recall reading years ago that seizures can be caused by abnormal calcium channels (I presume in the brain). I also have osteoporosis (first diagnosed at approx age 32) – for no apparent reason, which also suggests deregulated calcium management (with insufficient calcium deposition into the bones). I cannot tolerate much dairy, and I have still never found a calcium supplement that I can tolerate. P.S. Fortunately, (after 35 years with occasional brutal seizures) I found an anti-convulsant that stopped all seizures (Levetiracetam). No other anti-convulsants (of many tried) were effective. My experience seems to support others’ reports of convulsive spasms/jerks, and calcium management/utilization abnormalities.

Hi Dave – just to let you know, anti epilepsy medications are a known risk factor for osteoporosis, because they can cause vitamin D levels to be very low. Please make sure your vitamin D levels are adequate.

Thanks Dave W for adding to the discussion and I am glad you found the right medication!

I can confirm epilepsy has been ruled out in my case both because of the nature of “jerks” and based on an EEG (had it checked because of one case of epilepsy in the family).

cort’s point about short strength exercises being possibly (??) the way to work with our broken systems got me researching… the workwell foundation have said similar things… here’s an article from way back in 2004, https://workwellfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/When-Working-Out-Doesnt-Work-Out.pdf

and a more recent talk on youtube saying the same

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q_cnva7zyKM&t=1236s

i’d love to hear any other experiences or knowledge people have around this…

Glad to see that – thanks Tom.

The best form of “exercise” in my personal ME/CFS experience is not anything related to strength building, but everything gentle related to keeping the fascial system fluid (if that’s possible within energy envelope). Like a few specific stretches in the evening to release some tension before bed, self-massaging calves/feet, and mental muscle relaxation exercises. If still possible within energy envelope and without cramping muscles or pain, going for a simple walk, or a few basic yoga exercises. (Right now, I can only do the stretches ;-). American chiropractics treatment helped get the body more flexible, too.

I feel a short lifting of a grocery delivery box last week contributed to current crash; as did some other lifting some time ago. In the state I’m in now lifting an electric kettle overexerts. When energy was better, yeah I think I enjoyed short fun activity bouts for a few minutes until energy ran out, such as dancing to a single song, or bouncing/catching a rubber ball around the flat 🙂

So I think in no way could “short strength exercise” be a safe general recommendation!

Interestingly, I just found I had a slightly too high LDH (Lactate Dehydrogenase) in a recent exam – wonder if that could relate to anaerobic metabolism.

Cort, if you ever have more information on how adrenaline or positive excitement mobilises energy in ME/CFS patients (and if that is aerobic or some kind of fallback anaerobic metabolic pathway?), I would be really interested in reading about that. I’ve observed that adrenaline/positive excitement mobilises what feels like an unsustainable kind of energy that masks perception of true exertion limits, and only makes me crash the harder once adrenaline wanes. Have been wondering what happens there on the metabolic level.

I had no symptoms of the sort described in this paper after having COVID, however one year later I took the first and second vaccine. In the year since I took the vaccine I have experienced a marked decrease in exercise tolerance and stamina. I bike a lot, and know my home trails intimately; I now have to push up hills that I have always ridden in the past, before taking the vaccine. I feel I have sabotaged my health by taking that stupid vaccine, which I did not need at all. It depresses me so much to know that I voluntarily took it, and that there was so much pressure to do so from so many directions.