Thanks again to Patrick for letting Health Rising publish his blog. In it Patrick opens up new ground on a topic that hasn’t received the attention it deserves – the unusual thirst that many people with ME/CFS experience. Please note this is a long (but very well-written) blog. You might want to take it in chunks and check out the Gist.

Water – it’s the stuff of life – but drinking too much can be dangerous.

It’s not in the guidelines. Nor is it in most symptom lists, but it’s hard to ignore the fact that many people with ME/CFS patients suffer from could be termed “excessive thirst”.

The now-retired Dr. David Bell said that his ME/CFS patients could drink up to three gallons (11.5 litres) daily. Meanwhile, Dr. Jacob Teitelbaum more colourfully states that ME/CFS patients can ‘drink like fish and pee like racehorses’.

Searches for terms like ‘thirst’ and ‘dehydration’ on ME/CFS forums such as phoenixrising.me will return hundreds of posts in which patients discuss this symptom. I’ve read through the majority of these. The nature of the thirst is described similarly across the board: it tends to be unquenchable, to involve dilute urine and to get worse during episodes of post-exertional malaise.

While these factors seem to be nearly constant, some patients can also develop hyponatremia (low blood sodium) and some suffer from the symptom more severely than others. Indeed, while some patients might ‘only’ drink four or five litres of water per day, a minority of others are so severely affected that they might drink up to 20. But why is this thirst happening and what can be done about it?

This was a question that, at one time, I had to answer urgently.

Patrick’s Story with Life-Threatening Hyponatremia (Low Blood Sodium Levels)

I have had ME/CFS for five years. For the first half of that time, I certainly experienced increased thirst, typically drinking around four litres of water per day. It was unpleasant at times but it didn’t bother me too much.

In mid-2020 however, that all changed and, for a six-month period, I entered into a personal hell. My ‘good’ days involved drinking around eight litres but when I crashed, the thirst was so extreme and all-encompassing that I could drink 20 litres (over 5 gallons) of water in a 24-hour period.

The symptoms were worse at night. There were around a dozen nights over this period when the thirst prevented any sleep at all. On one occasion, I did not sleep for three nights out of four. But it wasn’t just thirst in isolation. I felt that I was drying up inside and that blood was not reaching my skin and brain in a profound way (although I did not understand the significance of this at the time). I am not at all exaggerating to say that I felt like I was fighting for the morning light at those times and that I feared that my body could not sustain the strain that it was under for much longer.

One of the most difficult things about this nightmare was that I had no idea what to do about it. And so, in January 2021, feeling like I had no other option, I packed a bag and presented myself to my local A&E in Dublin. There, it was found that I had a profound hyponatremia of 116 (normal range: 135-145). Such a severe level of hyponatremia is strongly associated with the development of cerebral edema, something which can induce a coma and lead to death.

At the hospital, Patrick was found to have hyponatremia – dangerously low blood sodium levels.

That week in hospital was very challenging: blood tests were taken morning and night every two hours. Early on in my stay, my blood sodium levels auto-corrected too quickly. This is a known risk factor for serious forms of brain damage and I had to be put on a drip along with desmopressin injections to bring my sodium levels back down again (desmopressin is a medication that has essentially the same effect as vasopressin/antidiuretic hormone, the hormone that conserves water). As I read later in my medical records, I was being treated, for the most part, like an intensive care patient albeit in a standard ward. My case was considered ‘tenuous’ which, in medical terms, means ‘touch and go’.

Throughout that time, I tried to tell the doctors that ME/CFS patients tended to suffer from excessive thirst. I told them about a paper (by Dr. Miwa from 2016) that had found reduced levels of salt and water-retention hormones in the illness. Perhaps that was something to do with what I was experiencing? No one listened though and later my medical records stated simply (and inaccurately on every count): ‘Patient was admitted with self-diagnosed ME due to having non-specific symptoms’.

In the hospital, I was diagnosed as having a mental health condition called ‘psychogenic polydipsia’ (also known as ‘primary polydipsia’). In this condition, it is assumed that people are drinking enormous quantities of water in the absence of any physiological need and only because of mental illness.

I knew that I was being treated like a mental case throughout my stay. At various times, I was told: ‘You’re only in here because of drinking so much water’ and ‘Will we have to go with you to the toilet in case you drink behind our back?’ At one point, standing near to the hallway, I overheard the doctor and nurse talking about my case. ‘So, in this ward, we have Patrick. And he’s been diagnosed with… primary polydipsia’. And then they laughed.

I said nothing about this diagnosis at the time. My blood sodium levels eventually normalized and I just wanted to get home.

Two weeks after I had left the hospital, I experienced another episode of post-exertional malaise. At the exact same time, the thirst came raging back. As before, drinking more water only made it worse. I didn’t want the same old vicious cycle to start up again: I had to work out what was really going on. Had I been drinking so much because I was mentally ill? Or was there something about ME/CFS that caused the thirst?

At one point, Patrick was drinking over 20 litres (5 gallons) of water a day.

I had been reading a book about hyponatremia by Prof. Tim Noakes. Titled ‘Waterlogged:, it examines the common problem of overhydration in professional athletes. Early in the book, there was a diagram about thirst physiology. Most of it was dedicated to the ‘osmotic thirst’ centre. This is the most common reason for thirst. It is triggered by classical dehydration and the answer is simply to drink more water.

But something else also caught my eye: the ‘hypovolemic thirst centre’. The brain’s second, and much lesser known, thirst centre is triggered when the plasma blood volume drops by 10% (c. 280 ml). And, in order to quench it, you need to drink something appropriately salty. Blood is salty stuff, after all, and pure water alone can never sustainably boost blood volume. It is, after all, the prerogative of the kidneys to filter water out. (For articles that describe hypovolemic thirst in more detail, see this paper and the relevant sections in this paper).

My mind raced furiously. I knew that ME/CFS patients routinely didn’t have enough blood because of mechanisms within their illness. Was this the reason why I had been so thirsty? And I had just been mistakenly – but understandably – applying the wrong solution to my problem?

I then remembered a study by Prof. Medow in which it was found that drinking Oral Rehydration Solution was as effective as a Saline IV for boosting blood volume. In Ireland, these little packets of salt, glucose, and potassium are sold under the brand name ‘Dioralyte’. I immediately went out to the nearby chemist, bought a box, and drank 600ml of the stuff.

My thirst reduced profoundly. I could feel blood getting back into my skin and brain. I could walk up a staircase without having to stop every step. The lights had switched back on.

At last, I had worked out the main reason for my extreme thirst. I wasn’t a mental case, after all. I had fought through the most horrendous symptoms, symptoms that had been created because my illness had reduced the amount of blood in my body. I had tried to resolve the resulting thirst signal in the wrong way. My thirst had never been looking for more water. Instead, you could say, that I had been thirsty for blood.

I was so glad to have mitigated my thirst that I simply tried to put a lid over my hospital experience and over the severe symptoms that I had suffered in the preceding months. To this day, I am still traumatized by the life-threatening symptoms that I experienced over that time, and for a long period afterwards, I just tried to move on with my life as best as I could. But later, as we shall see, I would come to revisit the whole experience – and my diagnosis as a ‘psychogenic water drinker’ – with a very different purpose in my mind.

So much for my personal story. How can we map out, in more precise and theoretical terms, why extreme thirst might be occurring in ME/CFS? Let’s consider this question now, first reminding ourselves of the findings on low blood volume in the illness and then mapping these findings onto thirst physiology.

Low Blood Volume in ME/CFS: A Summary of the Key Findings To-Date

While this is not a problem that affects all patients, it has been known for a long time that low blood volume is a central characteristic of ME/CFS. For example, back in 2002, a Harvard study found that ME/CFS patients had a 9% reduction in plasma blood volume in comparison to healthy controls.

However, later studies found that, when you categorise ME/CFS patients according to their illness severity, the more seriously ill patients tend to have an even more profound drop in blood volume. A 2018 study by Prof. Visser and Dr. Van Campen found that housebound ME/CFS patients with orthostatic intolerance had 23% less total blood volume than the physiological norm, a finding that echoes a 2010 study by Prof. Hurwitz et al. that had found a similar blood volume reduction among severe ME/CFS patients. Given that a healthy person tends to have around five litres of blood, this means that severe ME/CFS patients can be well over one litre short.

But why is this happening? Research has indicated that it is seemingly primarily because ME/CFS patients suffer from a physiological abnormality which goes against standard medical orthodoxy and teaching.

The Paradox

There is a hormonal system in the body known as the Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System (RAAS). The RAAS is tasked with retaining salt according to the body’s needs. In a healthy person, any excessive loss of salt (e.g. through sweating, vomiting or minor blood loss) will lead to the ramping up of RAAS activity in order to instruct the kidneys to preserve salt.

In ME/CFS, however, this mechanism does not work normally. Termed the RAAS ‘paradox’ by researchers, not only does it lead to excessive salt loss in the urine but even when a state of low blood volume has been established, the RAAS activity remains blunted. Outside of ME/CFS specialists, most doctors are unaware that this irregularity is even physiologically possible. The basic facts of the RAAS paradox in ME/CFS were described in a paper by Dr. Miwa in 2016, building on his earlier 2014 paper.

The Wirth-Scheibenbogen Hypothesis

Why is this downregulation occurring in the first place? Prof. Scheibenbogen and Prof. Wirth, in their 2020 big picture hypothesis for ME/CFS, suggest that the RAAS downregulation is occurring because of an upregulation of a competing system known as the Kallikrein-Kinin-System (KKS).

They propose that ME/CFS patients have blood vessels that, for both autoimmune and autonomic reasons, cannot vasodilate normally. This lack of normal vasodilatory function leads to the creation of an overall state of ‘global hypoperfusion’ within the illness (i.e. the blood just doesn’t perfuse adequately throughout the body, including into the muscles and brain).

The body tries to correct this vasodilation impairment by creating its own endogenous vasodilatory substances. These are manufactured by the KKS and include bradykinin. Unfortunately, this attempt is ultimately unsuccessful and comes with side effects. As the KKS and RAAS act in opposition to each other, the upregulation of one will lead to the downregulation of the other. As a result, the RAAS becomes suppressed, leading to salt loss, lowered plasma volume, and ultimately to a state of low blood volume that the body cannot correct itself. (For a very helpful write-up of this research by Prof. Scheibenbogen and Prof. Wirth, see the article by Cort)

I should mention that the RAAS blunting is not the only possible reason for the lowered blood volume in the illness. Prof. Wirth and Prof. Scheibenbogen also propose ‘vascular microleaks’ which might result in the loss of blood from the circulation into the interstitial space.

In addition, it has been noted that, in addition to lowered plasma volume, ME/CFS patients can have less red blood cell (RBC) volume than normal as well. There are two likely reasons for this. One is that the activity of the RAAS also modulates the activity of erythropoietin (EPO), the hormone responsible for creating red blood cells (RBC). If the RAAS activity is lowered, it is possible that EPO activity will also be reduced, thereby lowering RBC volume. Secondly, it is also feasible that the body might ‘sense’ the overall reduction in plasma blood volume and reduce RBC production in order to stay in some kind of physiological balance.

Both of these ideas were suggested by Prof. Satish Raj in his 2005 paper on the renin-angiotensin ‘paradox’ in POTS, a condition in which a similar phenomenon seems to occur. In general, it seems safe to suggest that, one way or another, the RAAS downregulation is the primary driver for the lowered blood volume within ME/CFS.

Thirsty for Blood? An ME/CFS Model of ‘Hypovolemic Dehydration’

Having explored the low blood volume within ME/CFS, how can we map that onto the excessive thirst within the condition?

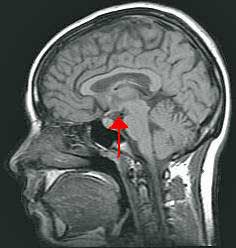

The small hypothalamus plays an important role in the hypovolemic thirst center.

First, we need to remember that the hypovolemic thirst centre is triggered when the plasma volume drops by 10%. Studies indicate that such a reduction is common in ME/CFS – suggesting that the hypovolemic thirst centre may be being triggered regularly.

Secondly, we also need to remember that the hypovolemic thirst centre is not ‘asking’ for water. Blood is salty stuff, and the ingested fluid needs to be capable of boosting blood volume. This is a crucial point. If someone is experiencing thirst, they will naturally assume that their body is ‘asking’ for them to drink water. Outside of researchers who specialize in thirst physiology, most people have no idea that the brain has two thirst centres and that each has quite different requirements in order to be ‘satisfied’.

Putting all of the above factors together, I suggest that the basic model for excessive thirst in ME/CFS looks something like this:

- Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone axis suppression >>>>

- Plasma blood volume drops by at least 10% (and ultimately likely stays at an even lower amount) >>>>

- Triggering of hypovolemic thirst centre (salt + water appetite) >>>>

- Patient understandably, but mistakenly, drinks pure water in response to their thirst >>>>

- water is urinated out shortly afterwards >>>>

- thirst is still present as low blood volume remains >>>>

- vicious cycle of unquenchable thirst and excessive urination develops.

Hypovolemic drinking of water can result in a nasty vicious circle – the thirstier you are – the more you drink – and the thirstier you become.

This model explains the key characteristics of thirst within ME/CFS. It is unquenchable as the wrong remedy is being applied. The urine is dilute because of the amount of water ingested. The thirst can worsen in a crash because, during those times, the RAAS suppression increases, resulting in additional solute loss and therefore in a worsening of hypovolemic thirst. And, finally, hyponatremia can develop for two reasons: the ingestion of a large amount of fluid dilutes the bloodstream and also because the RAAS downregulation is pulling sodium out of the body as a matter of course.

I am not suggesting that this model can explain every aspect of the thirst experienced by ME/CFS patients. Mast cell activation issues, inflammatory responses during post-exertional malaise, or neurological dysregulation (such as increased stress chemicals), among other things, likely all play a role. (There is an excellent paper by long-COVID patient and researcher Dr. Carroll on a wide range of possible general contributing factors to thirst that is well worth reading).

I would propose, though, that the ‘big reason’ why patients can end up drinking so many litres of water every day is likely because of their understandably applying the wrong solution to hypovolemic thirst. Indeed, in researching online forums for how patients have managed to ameliorate this symptom, I have observed consistently that the most profound improvement typically comes from efforts to increase blood volume.

If this model is correct, then what can be done to mitigate this symptom?

Treating Hypovolemic Thirst: Oral Rehydration Solution to the Rescue (or “The Solution That’s the Solution…”)

In speaking of treatment options, I will limit myself to discussing what has worked for me personally. The following is not medical advice and each person should determine their own treatments according to their individual needs and in consultation with their doctor.

The most helpful change I have made is to replace pure water with oral rehydration solution (ORS). Initially, I had drunk a mixture of ORS and of normal water daily. However, this approach is problematic as any normal water will work to pull out the electrolytes within the ORS, thereby somewhat negating its effect. By switching to drinking only ORS, I have made sure that all of the fluids I consume are also boosting plasma blood volume.

ORS achieves this effect because of something called the ‘sodium-glucose co-transporter’ in the gut. This mechanism allows for the gut to pull essentially all of the sodium neatly into the bloodstream, as long as that sodium is accompanied by a physiologically appropriate amount of glucose (or dextrose). In this way, ORS is akin to having a ‘Saline IV in your pocket’.

I do drink some normal water every day, usually a tiny amount to take some supplements and I might also have the occasional cup of tea or decaf coffee. But by switching to only drinking ORS for the vast majority of my fluids, I now only need to sip on around 2.5 litres of fluid per day. Given the nightmarish crash-days of drinking 15 (or more) litres some years ago, this change still feels miraculous to me.

Aside from ORS, my dietary salt consumption is otherwise moderate, at around 3-5 grams per day. I also find this helpful in quenching my hypovolemic thirst. However, I should note that when I experimented with consuming a lot of dietary salt (i.e. eating salty/salted foods rather than drinking ORS), as many ME patients do, I experienced some negative effects.

Drinking Oral Rehydration Solution vs Adding More Salt

Salt can impair vasodilation and, given that many ME patients appear to have problems with vasodilation (according, at least to the theory by Scheibenbogen and Wirth referred to above), excessive dietary salt could worsen that issue. Excessive salt can also interfere with mitochondrial function, can slow down the activity of the sodium-potassium pump (a key bodily process for energy creation within our cells and for muscle strength), and, at amounts of 12 grams daily at least, can cause muscle wasting. For an excellent overview of the potentially harmful effects of a high-salt diet, see this paper.

I also learned that hunter-gatherer groups, as a general rule, do not have more than 2.5 grams of salt daily (although some, as the last linked paper shows, like the Inuit, have around four grams and we, of course, cannot forget the pastoralist Maasai tribes of Tanzania who regularly drink the blood of their cattle. Although I haven’t tried it myself, perhaps this is the best natural cure for hypovolemic dehydration. 😉 )

High amounts of dietary salt will also cause classical dehydration, pulling water out of your cells via the process of osmosis. This dehydrates them and causes significant cellular stress. The body then must initiate a substantial repair job to get those cells back up and running normally. To take this phenomenon to its most extreme end, this is why drinking seawater can kill you. The resulting dehydration from such a high salt load is simply too severe for the body to recover from. In this way, a high salt diet, while mitigating hypovolemic thirst, will also increase osmotic thirst.

This difference between drinking ORS and just eating salt normally is very important. While, of course, a considerable amount of that salt will end up boosting blood volume (as was shown by this paper which measured the effect of a daily intake of 12 grams of salt on blood volume), high dietary salt can also have a negative effect on cellular function, as we have just explored.

In contrast, and to the best of my understanding, when you drink ORS, the salty solution will remain in the extracellular space, just like a saline IV. It is this ability of ORS to remain in the extracellular space (i.e. the intravascular plasma and the general extracellular fluid compartment) that makes it such a safe and medically neat option.

Drinking ORS not only helps profoundly with my thirst but has also reduced my heavy legs, improved my exercise tolerance, and helped calm down my nervous system. And the feeling of ‘internal volume expansion’, as the blood more easily reaches your brain and skin, offers significant relief.

On the other hand, I do not know if there are any long-term safety issues with drinking so much ORS. But my current thinking is that, in the grand scheme of things, drinking a solution that essentially just contains salt, glucose, and potassium probably falls into the category of more benign medical interventions.

These days, I drink a product called Normalyte, an ORS that was specifically developed for dysautonomia patients and which does not include unnecessary preservatives.

- Please note – The link to the Normalyte website is an affiliate link. 100% of the proceeds from sales through that affiliate link for the next month will be donated to Health Rising by Patrick.

However, it is important to mention that, whereas before my thirst level was at 100%, nowadays it hovers somewhere between 5% – 20%, depending on flare-ups in my illness. As mentioned earlier, I think it is likely that other issues also contribute to thirst in ME/CFS, although low blood volume is likely responsible for its most extreme – and dangerous – forms.

Ok, so we have now explored what might be causing excessive thirst in ME/CFS. Let us return to ‘psychogenic polydipsia’ and to the idea that some people are drinking so much water just because they are mentally ill.

Is ‘Psychogenic Polydipsia’ a Terrible Freudian Mistake?

Is the diagnosis of psychogenic polydipsia in ME/CFS a Freudian mistake?

After I had managed to resolve my extreme thirst through my own research, I tried to forget about the humiliating diagnosis that had been made in the hospital. Eighteen months later, however, a voice in the back of my mind was still nagging away at me: what is the history of this strange condition that suggests that patients, who are drinking enormous quantities of water and say that they are dying of thirst (and in some cases actually do pass away), are instead just stuck in some sort of strange mental compulsion to down as much fluid as possible? On what is it based and are its premises well-founded?

I spent a whole year researching this condition and, in the end, I concluded the following:

Primary polydipsia is a terrible Freudian mistake and what is termed ‘psychogenic water drinking’ has likely always been, at least in most cases, a misreading of the biomedical thirst that is experienced by ME/CFS and POTS patients.

I draw this conclusion for five key reasons.

(1) Firstly, the condition has received only the tiniest amount of research. A lifetime PubMed search for ‘psychogenic polydipsia’ will return less than 300 results. By way of contrast, a lifetime PubMed search for ‘multiple sclerosis’ will yield over 110,000 results. It has simply received very little interest, despite the fact that it is recognized that so-called primary polydipsia patients can die from severe hyponatremia.

(2) Secondly, the understanding of the condition essentially hasn’t budged since the late 1950s. Writing in 2017, Prof. Daniel Bichet of the University of Montreal noted:

‘Our understanding of the pathophysiology of this disease has made little progress since [a 1959 paper by Barlow and De Wardener]’.

At present, the condition is a kind of medical relic, still operating on assumptions that were developed well over six decades ago. Those assumptions made sense in the context of medical knowledge at the time but, as we shall see with reason no. five below, are totally inadequate in light of current medical understanding.

The Gist

- Many ME/CFS patients suffer from polydipsia – a condition that involves unquenchable thirst, dilute urine, a worsening of thirst during post-exertional malaise (PEM) and, at least in some patients, the development of hyponatraemia (low blood sodium).

- Patrick Ussher, an Irish ME/CFS patient, used to suffer from this symptom at its most extreme – to the point that he developed life-threatening hyponatraemia and was hospitalised.

- In the hospital, he was diagnosed with a mental health condition, ‘psychogenic polydipsia’, in which it is assumed that patients drink enormous quantities of water in the absence of physiological needs and because they are mentally ill.

- After his hospital stay, Patrick managed to resolve his extreme thirst through his own research and later wrote a (free) book about what might be causing thirst in ME/CFS (details to follow).

- In Patrick’s hypothesis, excessive thirst in ME/CFS is mainly caused by the low blood volume that is characteristic of the illness. Research has consistently found that ME/CFS patients do not have enough blood, with some patients short by a litre or more. The most significant reason for this reduction in blood volume appears to be the suppression of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone axis, a hormonal system which controls salt levels in the body.

- The brain actually has two distinct thirst centres: osmotic (triggered when the body’s water content is too low) and hypovolemic (triggered when the plasma blood volume drops by 10%). It is this little-known second thirst centre that is likely being triggered continuously in ME/CFS patients.

- Crucially, the hypovolemic thirst centre is not ‘looking’ for water in order to be ‘quenched’. Blood is salty stuff and, in order to boost blood volume, the ingested fluids need to be appropriately salty.

- Patrick believes that most ME/CFS patients fall into the understandable trap of just drinking pure water in response to their thirst (for who doesn’t drink water when they are thirsty?). When this water is excreted by the kidneys, though, the blood volume will remain low and, as a result, the thirst will continue – and even grow – as sodium levels and blood volume continue to drop.

- When Patrick switched from drinking pure water to drinking ORS (oral rehydration solutions), he experienced a profound decrease in his thirst along with a significant improvement in his quality of life. In previous research, ORS has been shown to increase blood volume as effectively as a saline IV in POTS patients.

- Later on, Patrick researched ‘psychogenic polydipsia’ in detail. He found that it is a condition which has received little research and which is generally regarded as a ‘medical mystery’. In fact, several leading academics have suggested that the supposed ‘psychogenic’ basis might be a mistake and that the real mechanisms simply haven’t been identified yet.

- When Patrick researched the earliest papers into the condition from the 1940s and 50s, he came across several intriguing patient case studies. Those patients had symptoms reminiscent of ME/CFS such as ‘aching everywhere’ and profound ‘weakness of the legs’. Among other reasons, this led Patrick to believe that, at least in many patients, what has always been termed ‘psychogenic polydipsia’ may have been a misreading of the biomedical thirst experienced in ME/CFS patients.

- Patrick’s book challenges the psychogenic basis of ‘psychogenic polydipsia’ (also known as ‘primary polydipsia’) and instead maps out a model of ‘hypovolemic thirst’ which can explain the symptoms in organic terms. The book is called ‘The Myth of Primary Polydipsia: Why Hypovolemic Dehydration Can Explain the Real Physiological Basis of So-Called Psychogenic Water Drinking’. It is available on Amazon and from themythofprimarypolydipsia.com as a PDF download.

- At its most extreme, this symptom can lead to hyponatraemia-induced coma and death. Despite this, the current diagnosis of ‘psychogenic water drinking’ offers only stigmatisation and no practical help. If ‘hypovolemic dehydration’ could re-explain these symptoms in organic terms, it would not only lead to much-needed medical help but also to greater awareness about the biomedical nature of ME/CFS among future medical students.

- Patrick is looking for doctors/medical researchers who may wish to work on a hypothesis paper or other similar collaborations.

‘The pathogenesis of insatiable thirst and excessive fluid intake as seen in primary polydipsia remains largely unknown’.

Most notably, Prof. Daniel Bichet says: ‘The diagnosis of compulsive water drinking must be made with care and may represent our ignorance of as yet undiscovered pathophysiological mechanisms’. (‘Compulsive Water Drinking’ is yet another term for ‘primary/psychogenic polydipsia’). As all ME/CFS patients will be aware, just because the cause of a medical issue is unknown does not mean that that medical problem is caused by mental illness.

(4) Fourthly, when you return to the early papers which researched so-called ‘psychogenic water drinking’, it seems clear that many of the patients under examination actually suffered from ME/CFS. For example, in the aforementioned 1959 paper by Barlow and De Wardener, titled ‘Compulsive Water Drinking’, patients reported symptoms such as ‘aching everywhere’ and ‘breathlessness upon exertion’ as well as developing their health problems following previous illnesses and other acute stressors, a pattern which matches the typical development of ME/CFS. One patient was even described as having ‘hysterical weakness of the legs’, which would seem to me to be a rather Freudian characterization of post-exertional malaise.

Indeed, Freudianism abounds in that paper. Patients were assumed to drink so much water simply because of being ‘emotionally disturbed’. Their troubled childhoods, adolescences and unsatisfactory sex lives were also scrutinized. An earlier paper about so-called psychogenic polydipsia even concluded that being homosexual was a likely cause as patients supposedly developed a subconscious obsession with the ‘oral libidinal zones’ as a surrogate activity for heterosexual sex. So much for the scientific method in action.

(5) Fifthly and finally, the discovery of the brain’s second thirst centre, the hypovolemic thirst centre, was not made until the 1960s, long after the idea of ‘psychogenic water drinking’ had taken hold. It is this thirst centre that can, along with the hypovolemia within ME/CFS and POTS, explain the typical symptom presentation that is seen in so-called ‘primary polydipsia’.

Indeed, that typical symptom presentation is hyponatremia and dilute urine, exactly the same features that are observed in thirsty ME/CFS patients. Most notably, I have come across several ME/CFS patients in forums who have suffered the (mis)diagnosis of primary polydipsia (see here and here), including an ME/CFS patient from whom fluids were forcibly restricted (as reported in this thread).

Faulty Test?

At the moment, primary polydipsia is diagnosed by using the ‘water deprivation test’. Patients are forbidden from drinking water for an extended period of time to see whether their bodies can produce concentrated urine. If their bodies can, this is taken as evidence that vasopressin/antidiuretic hormone function is intact. If vasopressin, the principal job of which is to conserve water, can work then, or so the thinking goes, there can be no reason for a patient to drink so much water.

But what if the thirst was never about water at all but instead about blood? What if the issue is nothing to do with vasopressin but originates in the suppression of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system? In this case, finding that vasopressin can work is the medical equivalent of examining an elbow, declaring it to be in good condition and that all is well, while that patient is actually suffering from a broken leg and screaming in agony.

In fact, my research has uncovered two papers on so-called Primary Polydipsia that found evidence of RAAS suppression. One paper from Japan found a downregulation of the RAAS in so-called psychogenic water drinkers while a paper from Belgium observed that so-called compulsive water drinkers lost large amounts of solute for some kind of endogenous reason. That paper’s author wondered if it was something to do with a problem in the RAAS.

Were these two papers unknowingly just studying thirsty and undiagnosed ME/CFS patients? The implications of both articles were never pursued however and the status quo remained: such patients are just drinking so much water because they are mentally ill.

To be clear, some people do drink excessive fluid for psychological reasons but such people never cite thirst as a motivator. They may do so for health reasons or because of some kind of misplaced advice. For example, one man developed profound hyponatremia as a result of drinking large volumes of water in order to suppress his chronic hiccups.[1] There may also exist a distinct pathophysiology within schizophrenia that creates excessive thirst and this phenomenon might represent a specific subset of so-called primary polydipsia patients (for more detail, see the section on severe mental illness in this paper).

“The Myth of Primary Polydipsia”

Patrick’s book challenges the notion that the thirst or polydipsia in ME/CFS and related diseases is “psychogenic” in nature.

I strongly believe that, in general, what has been termed ‘psychogenic water drinking’ has been a misreading of the thirst experienced by ME/CFS and POTS patients. In order to make my case, I have written a book.

Titled ‘The Myth of Primary Polydipsia: Why Hypovolemic Dehydration Can Explain the Real Physiological Basis of So-Called Psychogenic Water Drinking’, it traces the early Freudian research into primary polydipsia, explores the findings into low blood volume in ME/CFS and POTS, contains many ME/CFS patient testimonies regarding this symptom and describes possible treatment options. In my view, the ‘medical mystery’ of so-called primary polydipsia was always likely to be explained by a blind spot in medical thinking and that blind spot may well be ME/CFS.

The book is available as a free download here or as a paperback from Amazon. The book also includes research into long COVID, in which two large survey-based research papers have found that around 35-40% of patients report intense thirst as a symptom (see here and here). It seems highly likely that hypovolemia is a key factor in the thirst experienced by long-COVID patients as well.

Primary polydipsia currently amounts to unintentional medical negligence. Patients who say they are dying of thirst, and in some cases do pass away, are stigmatized by this diagnosis and receive no practical help regarding how to mitigate their symptoms. This is an appalling situation and it must change both so as to save lives and to mitigate intense suffering.

A Boon to ME/CFS?

But if ME/CFS actually holds the clue to demystifying so-called ‘psychogenic water drinking’ then could the current debacle of primary polydipsia contribute to changing the perception towards ME/CFS in the wider medical community?

This is because all current doctors are taught about primary polydipsia while in medical school. If this could one day be replaced with teachings on ‘hypovolemic thirst’, then the mechanisms that create that thirst within ME/CFS would have to be taught instead, alongside other typical causes of thirst, such as Type II diabetes, diabetes insipidus, kidney issues and so on.

Who then would leave medical school, having learned that ME patients are often over a litre short of blood due to their illness, without recognizing the seriousness of ME/CFS? Would such a change not lead to increased interest in the condition and to a much greater likelihood that future ME/CFS patients would be listened to rather than gaslighted, dismissed, and left to suffer on their own?

Such future medical students might well ask why their profession had not been taught, in the first place, about the research into such a debilitating condition. And they would be right to wonder.

Watch a talk that Patrick gave to The Irish ME Trust about thirst in ME/CFS

And a summary video about why Primary Polydipsia might be a terrible, Freudian mistake.

About The Author

Besides having and writing about ME/CFS, Patrick Ussher is a classical composer, a founder of the Modern Stoicism Project, and the author of a book on stoicism and Buddhism.

Patrick Ussher runs a YouTube channel, Understanding Myalgic Encephalomyelitis, aimed at simplifying ME/CFS and Long Covid research as well as sharing treatment strategies he has tried. His new book (published early 2025) is Understanding ME/CFS & Strategies for Healing, which explains for other patients the breakthrough ME/CFS research of Prof. Klaus Wirth and Prof. Carmen Scheibenbogen, as well as treatments which Patrick has found useful in improving his condition.

He is also a composer of music in a contemporary classical style. His music is part of the Artlist catalogue and can also be listened to on Spotify.

He is the author of Stoicism & Western Buddhism: A Reflection on Two Philosophical Ways of Life He has also recently written a pseudonymous political satire.

While a Classics PhD student, he was a founding member of the Modern Stoicism project, an interdisciplinary collaboration between academics and psychotherapists working to create modern applications of the ancient Greco-Roman philosophy of Stoicism. As part of that project, he started and ran the project’s blog from 2012 to 2016 and he also edited two books: Stoicism Today: Selected Writings, Volumes 1 & 2.

In 2018, he worked with Columba Press on a new edition of a book by his late mother, Mary Redmond-Ussher, on coping with breast cancer under the title Following the Pink Ribbon Path. Patrick has a BA and MA in Classics (Ancient Greek & Latin) from the University of Exeter, UK. His website is: www.patrickussher.com

Health Rising’s BIG (little) Donation Drive Update

Health Rising provides access to a wide range of viewpoints from the ME/CFS/FM/long-COVID communities. If that supports you, please support us.

Thanks to the approximately 200 people who have supported Health Rising thus far. Patrick’s blog demonstrates another feature of Health Rising – the access it provides to the creativity found in our communities. People with ME/CFS, FM, long COVID, etc., are constantly breaking new ground in how we understand and treat these diseases.

During 2023, Health Rising has featured blogs by Patrick (polydipsia, apheresis), Bronc (Armin Alaedini), Efthymios (artificial intelligence), Patrick Allard (recovery), Melissa Wright (cerebral spinal fluid leaks, recovery), Brian Vastag (Intramural research study), Alice Kennedy (languaging long COVID), Adam (BCG vaccination story) and others that are casting new light on ME/CFS and related diseases. If you find this access to the community helpful, please support Health Rising in a way that works for you.

I drank a fair bit too though never enough to cause an issue but in my case it was undiagnosed Hypercalcemia/Primary-hyperparathyroidism it was always coffee I drank & never water though either. Others noticed it more than me I think.

Thank you for sharing this. This is why it is so important to check everything out (although, of course, if nothing else is found, then the diagnosis will likely be ‘psychogenic water drinking’). Is there a treatment for hypercalcemia and how is your thirst doing now?

I have low blood volume ( tested years ago). I almost always have labs that show low sodium no matter how much salt I eat. I crave salt and eat popcorn often. Water runs right thru me.

I receive IV Saline 2x/week. pee most of the night when I do. My skin, eyes and mucus membranes tend towards dryness.

After 30 years of this it is obvious my body is trying to flush out fluids. I drink pedialyte occasionally. And an electrolyte drink called Roar. Don’t notice much.

May be worth trying normalyte inbetween infusions.

Thanks for the info!

Thank you Corinne for sharing your experience.

In chapter three of my book, I have a collection of ME/CFS patient testimonies regarding thirst. One of them was already drinking electrolytes, adding salt to all his food but was still drinking seven litres a day. His doctor then suggested that he cut out ALL plain water (or 90% anyway) and only drink oral rehydration solutions. That did the trick for that patient who then suddenly only needed to drink two litres of ORS per day.

When you drink a lot of plain water and then drink ORS, the former cancels out the effect of the latter, at least to a degree. The plain water will pull the sodium out.

I thought this might perhaps be of interest to you.

I didn’t read most of the Article as it was beyond my mental capacity. So this may have been addressed. But what about those of us with

Pretty bad orthostatic Hypotension who not only do not have excessive thirst but have almost no thirst And feel worse when we drink water. Thanks! And thanks for your work!

Hi Wendy, Indeed, this also seems to happen for some people. It’s not addressed in the article and I’m sorry that I don’t have any ideas on this but maybe some else will.

The treatment for Primary-Hyperparathyroidism(pHPT) is surgery to remove the hyper active gland/glands some cases pHPT are believed to be sporadic but others are genetic in origin caused by DNA SNP’s on the MEN or RET gene. Mine seems to have been caused by a SNP on the RET proto-oncogene which is associated with MEN2. It’s hard to find specific info on the different SNP’s with some seemingly contradictory info depending on which site one is on. see https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/variation/13952/?oq=rs2435357&m=NM_020975.6(RET):c.73%209277T%3EC see also https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng132 see also https://www.thyroid.org/multiple-endocrine-neoplasia-men-type-2/ see also https://www.facebook.com/photo?fbid=286594257701245&set=a.100543726306300 see also https://www.parathyroid.com/parathyroid-symptoms.htm

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4316409/

@flora, interesting. are you sure it was hypercalcemia instead of hypocalcemia?

Yes I’m certain it was Primary-Hyperparathyroidism as I had an Adenoma removed & my serum Ca was 2.7 & PTH was 200.

I experienced the danger and horror of a rather intense polydipsia event – at least for me – a couple of times when I was camping in very hot weather. Interestingly, it was worse at night.

Drinking only made my thirst more intense, my mouth drier than ever. Thankfully, it just happened a couple of times but it was peculiarly horrifying…I really didn’t see a way other stopping to drink – which my body was telling me to do.

I feel for what Patrick went through….

Other than that I notice that when I drink much water and I’m eating I do pee like a horse – lots of clean, clear urine. One person who watched me get up again and again thought I had diabetes insipidus.

Thank you Cort for your kind words. Honestly, I’ve no idea to this day how I survived that period.

Seems likely that the hot weather might have caused a lot of sweating, leading to a lower than usual blood volume (on top of hypovolemic ME mechanisms) and then your thirst.

Your intuition at that time *not* to drink is interesting. Guzzling more and more plain water only makes this issue worse but, when the thirst is raging, it is near impossible for most people not to just want to reach for more water.

Interestingly, when I was forced to undergo the water deprivation test in hospital, in which I didn’t drink for 18 hours, my thirst actually lessened at around the 14 hour mark. At the exact same time, my sodium levels normalised.

So my thirst lessened at the moment my blood reached a normal concentration again. How strange it was that drinking nothing at all actually lessened my thirst but I believe this ties in with my hypothesis – this thirst really is nothing to do with water. Normally concentrated blood is important from a blood volume point of view – there is then a ‘platform’ on which to build and then the hypovolemic thirst centre is probably a bit happier also.

I’m sort of baffled. In what way is this — (problem being described by many here) — NOT diabetes insipidus?

The Mayo Clinic’s very basic list of symptoms in adults:

* Being very thirsty, often with a preference for cold water.

* Making large amounts of pale urine.

* Getting up to urinate and drink water often during the night.

The condition can be caused by a lot of drugs. Lithium is especially notable. Also (my personal opinion) in smokers and certain occupations or exposures.

Sometimes it is reversible, here is an article (cite & brief other info):

Camelia G. Garofeanu, et al. Causes of reversible nephrogenic diabetes insipidus: A systematic review, American Journal of Kidney Diseases, Vol 45, Issue 4, 2005, Pages 626-637,

Background: In nephrogenic diabetes insipidus (NDI), the kidney is unable to produce concentrated urine because of the insensitivity of the distal nephron to antidiuretic hormone (arginine vasopressin). In settings in which fluid intake cannot be maintained, this may result in severe dehydration and electrolyte imbalances.

Conclusion: Most risk factors for reversible NDI were medications, and their identification and removal resulted in resolution of the condition. Long-term treatment with lithium seemed to result in irreversible NDI.

Thank you for raising this very important point.

DI can indeed look similar to the kind of extreme thirst I’m describing, at least from the outside, but it is actually completely unrelated.

DI is caused by the brain’s inability to produce any (or almost any) the antidiuretic hormone. Crucially, this lack of ADH means that DI patients tend to end up suffering from hyper- and not hypo-natraemia. This is because the lack of ADH causes a loss of internal free water, causing in turn increased sodium concentration and internal dehydration. In contrast, ME patients tend to end up with hyponatraemia.

Put very simply, the extreme thirst in DI is entirely related to the inability of the body to hold onto water, nothing else. In ME/CFS, the likely principal reason is the reduction of blood volume from RAA axis suppression. So in DI, the thirst is about water whereas in ME/CFS, I believe the thirst is about blood.

Diabetes insipidus has been linked or connected to Aquaporin 2, a water channel. Abbreviated as AQP. It is possible to find really technical information at the government website known as OMIM. Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man.

* 107777 AQUAPORIN 2; AQP2

Alternative titles; symbols: AQUAPORIN-CD

HGNC Approved Gene Symbol: AQP2

Cytogenetic location: 12q13.12 Genomic coordinates (GRCh38): 12:49,950,737-49,958,878 (from NCBI)

At the University of Groningen, there is a Prof Knoers who (along with others) has studied diabetes insipidus for perhaps as much as 30 years.

It might be looking into her research.

Also, Alan Verkman at UCSF has been studying, especially, AQP4 — here is brief information from abstract of one article: “Drugs targeting aquaporins have broad potential clinical applications, including cancer, obesity, edema, glaucoma, skin diseases and others. The astrocyte water channel aquaporin-4 is a particularly compelling target because of its role of brain water movement, neuroexcitation and glia scarring, and because it is the target of pathogenic autoantibodies in the neuroinflammatory demyelinating disease neuromyelitis optica.”

It could be Primary-Hyperparathyroidism as I struggled a lot in the heat too. There is even a type of normal calcemic Hyperparathyroidism where high normal Ca & high normal PTH or High PTH. I don’t believe I was ever checked for this before 2022 when I was literally so weak I could barely stand up it seems they only ever check ones PTH levels if they find high Ca.

Dr. Cheney advised us to drink 1/8 – 1/4 tsp of salt with every other glass of water and then 1/8 – 1/4 tsp of “no salt” (basically potassium) with every other glass of water. He said it was to increase blood volume. I have not done this in quite a while, but I have experienced the feeling that when I drink water it just “goes right through me.” When that happens now I add an electrolyte to water called “Hydrate” by “Goodonya” that is composed of lemon juice power, magnesium sea minerals, organic coconut water powder, organic stevia leaf extract, himalayan pink salt and vitamin C. It does the trick for me. And when I crave salty foods, I try to drink more water with Hydrate in it.

Thank you for sharing. The plain water ‘passing right through’ people is a phenomenon I’ve seen repeated across accounts of this symptom in the forums. Glad you’ve found something that works for you.

I am a long time sufferer of ME/CFS. Despite this I have spent a lifetime doing hard physical work, with periods of collapse. I, too, have suffered periods of extreme thirst, accompanied by drinking liters of water. This culminated with two hospitalisations after blacking out and collapsing. I was diagnosed with hypovolemia (low blood volume), hyponatremia (low sodium), both due to psychogenic polydipsia. I was diagnosed as a nut case! I tried to explain that I felt like I was going to black out if I did not drink water, my thirst was so overpowering I never went anywhere without at least one, and often three or four liters of water with me for longer trips. All in my head I was told. I had to learn to control my intake, it was mind over matter. Except that as my blood volume diminished through urination, I would experience severe hypotension, feeling very shaky with internal trembling, and a general weakness. Finally I learned, through much experimentation, I needed a lot of salt. I start out the day with a quarter to half teaspoon of salt dissolved in my tea, and apply liberally salt to anything during the day. I experimented with a potassium salt additionally, for me it had extremely deleterious effects, I felt I would black out, at times within minutes of taking it. I do eat a lot of fruit, but high potassium fruits such as melon or watermelon must be accompanied by salt. I have assumed that in addition to ME/CFS that I must have an adrenal problem related to aldosterone, and did have myself checked for cortisol and DHEA, both of which were low, but not dreadfully or dramatically so. The hormonal pathways are extremely complex in this regard, rather than turn myself over to doctors after my horrible past experiences I have instead continued to fine tune what works for me, and continue to experiment with many, many different vitamins, minerals, amino acids, and other natural substances. I did try both cortisol and DHEA, both made me feel awful, so I am certain the answer does not lie there, at least for me and despite my low test results. I would be very interested in hearing what works for others, what they have tried that has worked, and what has not. Interestingly, I think many people are walking around with hypovolemia, and are either unaware or are misdiagnosed. For me, the first symptom is a feeling of shakiness or internal trembling. It is often confused with low blood sugar, but it is also a symptom of hypovolemia, I believe most doctors are unaware of the possibility. I have been diagnosed with low blood sugar many times, starting first at age 16, which came after a bout of mono. I have had several glucose tolerance tests, none of which explained the severe feeling of shakiness, or internal trembling, I experienced. The theory I had low blood sugar did not correlate with the test, and sugar did not help. I want to thank you for this article, I have had this condition for decades, it is the first coherent explanation I have read or heard of. Almost brought tears to my eyes. I would like to see discussion of what has helped others.

James, I am very moved by your comment. It sounds like you have been through the real ringer with this symptom as I once did and, yes, it is a completely hellish experience at the most extreme end. And on top of that, you suffered the same ‘psychogenic’ diagnosis. I’m glad that you find my explanation helpful. One of my main motivations in writing the book is that people can have a guide out of these awful symptoms, in a situation where the medical system is happy to turn their back.

Also, James – I just want to echo the point you made about ‘shakiness’ being a sign of low blood volume. I 100% agree. This was one of the symptoms I used to have a lot back when I didn’t understand what I was facing.

Shakiness, trembling, weakness –

As blood glucose drops, adrenaline kicks in to rescue it.

Your blood glucose is restored to normal levels, but now you have that surge of adrenaline.

So the shaking can be from that surge. And you won’t ‘see’ the hypoglycemia in the tests, although that is what kicks off the stress reaction.

If you go to the… there is hypoglycemia association in the US. And they have studies of brain imaging, and they found that while blood tests are not registering a change in glucose levels, the brain experiences them first. That is, imaging does reveal the lowering. So, your body is experiencing the drops in sugar, is just the way they measure it that doesn’t.

This is harmful, this practice of gaslighting patients. You know what you are feeling.

I tested this many times with a glucometer, noting symptoms with what the readings were.

It’s a little bit scary how a high adrenaline state felt so… normal for me. Once I started taking thyroid, adrenaline normalized. Every once in a bit, I get a surge again and I’m baffled at how familiar that state feels… some are not even aware they are being run by adrenaline.

Thanks very much for sharing. Shakiness can be caused by hypoglycaemia but also can be caused by hypovolemia.

Hi – they are not indistinct phenomena.

“Hypovolaemia is a consequence of hypoglycaemia”

“However, the hypoglycaemia is not the only issue, since low blood glucose is usually accompanied by hypovolaemia. This relationship has been investigated in healthy volunteers [3–5] and in diabetics [6,7]”

Read the references mentioned [3-7].

https://doi.org/10.1080/00365510701541036

Wow – thank you for opening my mind to that connection. I’ll look into it further!

Enjoy 😉

https://raypeat.com/articles/articles/water.shtml

https://raypeat.com/articles/articles/leakiness.shtml

I have had thirst as a symptom for a decade now. It started when I moved to high altitude and was continuously an issue there. It’s improved a lot since I moved to sea level tho I’m still a thirsty person who likes to have a water bottle but no where near as bad as it used to be. This is very interesting article and I knew I wasn’t crazy or imagining this symptom

Thank you for the kind words, Rachel. That is very interesting about the change in thirst between altitude and sea level – I wonder why they might be

@rachel @patrick, i would hypothesize that the stronger effect at higher altitude may be because a lower [oxygen] is a stressor. @rachel, was it mainly when moving to higher altitude or also when you had already acclimatized (e.g. after 1 week staying there)?

@PeterMTDeen I was abnormally thirsty the entire ten years I lived at high altitude. I also blame the high altitude for triggering all of my symptoms and severe pain issues. While there all of my symptoms also became connected to the weather changes. It was like I could feel every change in the weather in my body. Now that I’m back at sea level and not dramatically thirsty regularly, the thing that will bring on my thirst and dry mouth is weather change, when it rains or snows I feel that old familiar thirst and need more water. Very weird and I’ll probably never know exactly why the high altitude hurt me but yes it does change ur bodies relationship with oxygen

A caution: I thought more NormaLyte would help with POTS, overdid it, ended up in the ER with blood pressure of 220 and a severe headache. The cure was to stop the NormaLyte for a few days. Now I use NormaLyte again, but need to be careful not to overdo, as my blood pressure is normally low, and I do not usually have headaches.

I use reverse osmosis water, thus it is even more important to pay attention to salt and electrolytes.

Many thanks, Patrick, for sharing your research and your story. Especially your work to reveal Primary Polydipsia for what it really is!

Thank you Helen for your supportive words. I will do my best to fight the PP situation, as energy allows 🙂

And thank you too for sharing your important note of caution. Can I ask how much Normalyte you were drinking daily to create the high BP and how much you drink now?

Patrick, I think it was a matter of increasing my dose of NormaLyte over time, to too much for me, which led to the high blood pressure. Now, I really am experimenting with doses of NormaLyte, and also Ionic Lytes (minerals but no dextrose). I imagine we all have to figure out the correct dose for our individual systems. I am grateful that I know to use these products, especially with RO water. I just have not gotten to the point of knowing what my correct dose is. Or maybe it changes depending on the day.

I also crave cold water, and am interested to learn more about whether that is harmful or potentially beneficial.

Thank you, Helen. I think I crave cold water too.

Hi. Try calcium.

I had very little calcium in my diet, started consuming lots of it, and then salt was finally having the effect of lowering heart rate and BP, not raising it through the roof like before.

You can look up D A McCarron’s studies and papers on calcium and tension.

Wow, M, I’d not given any thought to calcium, but it makes good sense, as I am unable to eat dairy. I’m going to give it a try. Thank you very much for taking the time to give me such a good suggestion!

I learned from here

https://raypeat.com/articles/articles/calcium.shtml

You can try a small amount of milk, like 10 ml, and slowly increase over weeks.

From a lifetime devoid of dairy to 1.5 ltrs a day.

Goodluck!

Thank you Patrick! I found this particularly interesting as even before my ME started I drank a lot of water and was constantly thirsty. I mentioned it to doctors and told them how I could leave the house for 10mins without a bottle of water, but it was never explored or even if any interest.

Does anyone know if/how this fits with Wirth & Scheibenbogen as they mention sodium overload but I don’t understand enough to figure out links? It’s mentioned towards the end of the abstract: https://translational-medicine.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12967-021-02833-2

Thank you for the kind words. Yes, ME patients can often be spotted because of all the water bottles they carry with them 😉

I have tried to think about the link to W&S’s hypothesis and high intracellular sodium. Now, I’m no biochemist so please – as it were – take the following with a pinch of salt (ahem)…but my understanding is that if you drink ORS, this will not have any negative effect on intracellular sodium function. The salt in the ORS should mainly stay extracellular. However, if you just add a lot of salt to your food, that salt might stress out the cellular sodium-potassium pump, lowering its activity (see link in my article in section on high dietary salt). That might theoretically lead to greater intracellular sodium concentrations because of the slowing down of the normal cellular mechanisms (though admittedly the paper in my article didn’t show that).

So the distinction I make (based on my current understanding) is between just eating tons of salt normally (this might not be a great idea) and drinking ORS (which I think is safer option).

But I can’t state anything with 100% certainty. Like a lot of ME patients, I’m doing my best to understand the illness but I don’t have a background in medical matters.

All that said, if you are craving salt, you probably need to eat in the normal way, as it were, until you are not craving it.

Thanks Patrick that’s really interesting. I do add a lot of salt to my meals for my POTS but I’ll experiment with drinking it too. I struggled with ORS when I tried it but I’m inspired to try again now.

Increased thirst can be associated with adrenal fatigue. Could this be connected?

Rachel, I had the same experience as you mentioned: since I moved to sea level, I don’t need to drink as much water. (Though I still drink way more than the average person when I am at home)

When I used to live at a higher altitude, I used to go jogging, exercising and swimming at a dam, drinking 2 liters of water in the 2 hours I usually used to spend there. (I used to be still thirsty after finishing the 2 liters of water)

These days, I go jogging and exercising at the beach and swimming in the (SALTY an mineral rich) sea, drinking NO WATER AT ALL during the 2 hours I usually spend there. And I don’t get thirsty at the beach. I suppose I get enough salt through the proses of osmoses while swimming in the ocean?

Furthermore: As part of multiple food sensitivities I developed through the years, I also got sensitive to salt: I can have NO salt in my diet at all – but can still swim in salt water. Yet, around the time I got sensitive to salt and had to completely stop my salt intake, I regained my ability to exercise, after years of being unable to exercise. I can however not draw any conclusions from my experience, because I don’t understand much of it.

Though I can not take salt, I do take a lot of magnesium and phosphate of potassium throughout the day.

Thank you Nicholas, very interesting. When I go on a low (dietary as opposed to ORS) salt regime, my muscles do ache less. I haven’t had such a profound stamina improvement as a result though – great that you had such an improvement. In my view, this speaks to the different effects on the body of ORS versus high dietary salt.

Yes, absolutely. Lowered adrenal output leads to less salt retention which leads to lowered blood volume. But I would suspect that the RAA axis reduction is the main culprit for this symptom.

Hi. Also the other way – salt lowers adrenal output

Good to see this blog from Patrick showing that our water thirst isn’t psychological.

For me, I can’t tolerate WHO ORS (world health organisation oral rehydration solution,) beyond when I’m eating.

When I was drinking WHO ORS all through the day I would upset my stomach quite a bit.

I had a family member telling me my breath smelt quite bad for for months, but my gentle hygiene was fine. I came to the conclusion that the WHO ORS was upsetting my stomach so much I had bad breath. How that worked. I’m not sure.

Sipping untreated water between meals still isn’t ideal, as I found myself drinking lots of water still. So I add a non-sugar electrolyte to my drinking water in my water bottle.

I drink this concentrate from New Zealand BioTrace Elite Electrolyte Liquid, and I find it significantly reduces my thirst, and water consumption to something much more reasonable like 2 to 3 litres per day. Rather than 4 to 5 litres per day.

Per Litre of water it has

Sodium 127mg

Potassium 132mg

Magnesium 45mg

Chloride 397mg

https://www.healthpost.co.nz/biotrace-elite-electrolyte-liquid-bteel1-p

Courts blog from 2020 here on Health, rising, has details on how to make the WHO ORS.

https://www.healthrising.org/blog/2020/09/15/saline-ors-oral-rehydration-pots-chronic-fatigue-syndrome/

Thank you Josh for this helpful tip. Some people indeed can’t tolerate ORS – particularly in the stomach. In some cases, this might be because of strange additives. There are purer versions available which may help some people with this issue.

Oh interesting. That happens even with the full WHO grams/litre?

Sodium Chloride 2.6g

Glucose 13.5g

Potassium Chloride 1.5g

Trisodium Citrate 2.9g

I’d be interested to know more detail about that, so I could consume more ORS. Is that in your book?

I only touch on it in the book but yes, even ‘proper’ ORS solutions can have very weird stuff added to them like flavourings, even ethanol in some cases. The ‘Pure’ version of Normalyte doesn’t have any of those things – see link in the article to that website where you can read about their formulation which was made with dysautonomia patients in mind.

@josh @patrick, I can imagine that the commercial ORS stuff contains conservatives, as the glucose concentration is such that, when not sterile or opened, it will allow bacteria to feed on it. is it possibly written on the package how it has been sterilized (filtration would be best, although one never knows whether some filter substances come along)

The Normalyte product is not a ORS. It doesn’t have any glucose. Isn’t the sodium-glucose co-transporter the key? Without glucose the electrolytes don’t stay in only the extracellular space, right?

Great question. The dextrose in Normalyte does the same work as glucose without the sweet test. They have the same chemical composition.

After clicking around Normalyte’s website, I did find products that contain the dextose, but it is only in their “hydration stick” mixes. However, the links in the article takes you to their main product “PURE Electrolyte Salt Capsules” and that does NOT have any sugar. See here: https://normalyte.com/cdn/shop/files/3sidesNormaLytePUREElectrolyteCapsules_1800x1800.png?v=1712782673

The capsules are okay for keeping electrolyte levels up (but they totally could have fit it into 1 capsule instead of 2).

Yes but their capsules are not ORS and will not be as effective at boosting blood volume

So this a thing? I didn’t read the article, but I get the gist.I crave ice water. I do have a RO filter, and put some drops of minerals in the water.. It is a little heaven to me.. I was always told cold water is no good. Recently I read that cold water stimulates the Vagas nerve somehow.. I will go by my instincts on this..I need ice water regularly..

@elaine, good point. putting something cold in your mouth, like frozen water in a plastic ball, reduces thirst (as it indicates to your body that water will come). may be another good way to reduce water intake (and therewith reduce hyponatremia).

Sorry, I just skimmed through your article. I will read it with more thoughtfulness later. But for now, the ice water is kind of doing it for me..A pleasure in the misery of my day..

Wow, I haven’t read the full article yet I’m reading it in parts, but I wanted to comment and say I’ve had problems with being thirsty since getting ME and have mentioned it to my doctor, but haven’t heard anyone with ME mention it till now. I drink a decent amount of water everyday and still find myself before bed feeling dehydrated with a dry mouth and throat as if I haven’t drank anything for a long time.The feeling stays even after drinking a full bottle of water, and at times seems to just make it worse. I also have problems with not retaining the water. Right after I drink the water to try to ease the dehydrated feeling, I have to use the bathroom over and over for a few hours. As soon as I use the bathroom my bladder is full again. This becomes problematic when I can’t sleep because I constantly need to use the restroom. I do think part of my problem is with salt intake issues from my PoTS, but I find it interesting that others with ME also have issues. Another weird symptom to add to my long ME problems list.🫠😵💫🥴

Thanks for sharing, Ruby. You are describing the way this is symptom is perfectly and I hope my article might help you get it under control.

Interesting! (and Thank-you Patrick and Cort). If it relates, I always feel “dry” (dry skin, little to no mucous production in the nose or lungs, dry eyes sometimes, and chronic constipation that water and fiber only makes worse). I also typically get up to urinate three times per night (or approx every 90 to 120 mins) which is (paradoxically) much more frequently than during the day. So, I can buy that our hydration is deranged!

Thank you Patrick! Since I got ME/CFS Ive been very thirsty and peeing frequently. I remember during one of my PEM episodes I felt really bad (as usual). I felt I needed desperately relief and just laid there w my eyes closed trying to listen to my body’s needs and suddenly salt popped up in my mind. I drank a glass of saline water and almost immediately I felt better. Since that episode I researched ME/CFS and salt and came upon ORS. I started only drinking electrolytes and really felt better. I still need to pee frequently and especially at night and I have dry mouth and eyes, but I don’t feel so thirsty. My electrolytes are back to normal values. Unfortunately, I also crave for dietary salt and understand this may worsen the condition. When I don’t get salt, though, my veins along my trough start throbbing and I feel bad until I get that salt. Should I worry when my levels are fine?

You are welcome, Gertrud. Despite the fact that high dietary salt intake might cause issues, as laid out in the article, I believe that the body’s response is also important. If you are craving salt, and feel better with it, you probably need it. Most of the papers examining high salt effects are not conducted in people with a condition that causes salt loss so everything needs to be understood in context.

Thank you Dave. Yes, I get the dryness too and I’ve read many accounts of this among thirsty ME patients. This has improved somewhat since I switched to ORS but it is still a troublesome symptom.

for many years i felt like i was dying of thirst. the more water i drank, the worse the feeling of thirst and the urge to drink became. a terrible cycle!

for the last 2 years i could only drink water with magnesium citrate. recently i’ve returned to a normal state and i feel it’s a really big step in all this dysfunctional cycle

I am the opposite, while I drink a lot normally, when in crash I have a complete absence of thirst.

Thank you Victoria. Yes, I’ve also seen some people say that they have very little or no thirst. Perhaps low blood volume is not such an issue for these people or something else is going on.

Yes – I very rarely experience thirst. My mother was the same way. Dad and I used to call her ‘the camel’ because she could go so long without.

I shared earlier in a comment that i feel much beter when i drank >6 ltr per day. Below 5, my bowel is dried out, muscle cramps etc, more brainfog. And no, i dont have diabetis.

Such a simple concept with great benefits. Best article of 2023.

I ONLY consume ors or a clean electrolyte powder in water now (and a cup of coffee for pleasure). I do not get thirsty anymore. This blood hydration/circulation has given me a good 60% improvement in QOL. I no longer crash after every activities. I can stand without PoTS symptoms. Miraculous.

I’m touched by your kind words, thank you.

And very interesting that you also had such significant improvements from switching to ORS/electrolytes only. Of all supplements, this approach has easily helped my quality of life the most. I fall apart without ORS.

Ha, ha, drink like fishes and pee like racehorses..I didn’t know this was a thing, maybe for some of us. I crave ice water a lot. I put mineral drops in my RO water, and am in heaven. Must be ice cold. I read recently that cold water stimulates the vagas nerve..something instinctual here?

Thank you, Patrick, for sharing your story with us – it explains so much for me personally. I’ve had ME/CFS for 2 decades and Fibromyalgia for 3 & was diagnosed with adrenal insufficiency over a decade ago. But for most of my life living in the hot, suffocating humidity of the south I assumed my extreme heat intolerance & unquenchable thirst was due to where I lived. Going outside my freshly washed & dried hair would within minutes look like I had just stepped out of the shower, wet hair dripping down the back of my shirt. I never leave the house without several bottles of water & I always have something to drink by my side. When I have to be somewhere that doesn’t allow drinks, I use sugar-free gum to help keep my mouth from getting too dry. And no amount of eye drops helps my extremely dry eyes – I was beginning to think that I may have Sjögren’s! My doctor tests my blood 3 times a year & my sodium levels are always below normal. I tell her its probably because I drink too many liquids & that almost all food prepared by others is way too salty for my taste. But your explanation for low blood volume makes sense to me. It could also explain why I drive 2 hours round-trip just to have my blood tests drawn. The phlebotomist there is the only one who can draw all of my blood tests in one or at most 2 sticks. Anywhere else, they have to stick me 5 or 6 times because my blood stops flowing into the vials. Could low blood volume explain this?

Hi Martha. Thanks so much for the kind words about the article.

I’ve seen seen in the online forums that it is common (in ME patients with thirst) to have slightly low sodium levels (and sometimes profoundly low ones, in extreme cases). This might be for two reasons. One is, yes, the amount people drink. But the other is that the very same RAA suppression that is creating the low blood volume is also, of course, pulling salt out of the body. So there are likely at least two reasons for the lower sodium levels.

Regarding the difficulty to get blood draws, I don’t know for sure if low blood volume makes this harder. It might well as peripheral circulation would be impaired. Another possibility are the microclots that have also been found in ME/CFS (search ‘help apheresis ussher’ on this site for my article on this). These thicken the blood and can make getting a blood draw harder in some people.

Thank you kindly for your reply, Patrick. I’d read the HR article on apheresis when it came out & wished I could try it – didn’t realize that was you! I’m fortunate that my doc offers EBOO & also IV infusions of glutathione and vitamins. I can only afford to see her 3 times a year as it involves travel out of state and an overnight hotel stay. It takes about 2 hours for the EBOO & the 2 IV treatments, in addition to the 45-minute doctor appt. My insurance only covers the doctor appt. I’m afraid you’re spot on about micro-clots with ME/CFS. My doc has me on Lumbrokinase for elevated Fibrinogen & monitors my D-Dimer, TAT Complex, etc. Thanks for the link to Normalyte. I just ordered some sticks, capsules & compression socks. Cheers!

Martha, just ran accross this today:

“Post-COVID exercise intolerance is associated with capillary alterations and immune dysregulations in skeletal muscles”

From the Abstract: “We present an in-depth analysis of skeletal muscle biopsies obtained from eleven patients suffering from enduring fatigue and post-exertional malaise after an infection with SARS-CoV-2. Compared to two independent historical control cohorts, patients with post-COVID exertion intolerance had fewer capillaries, thicker capillary basement membranes and increased numbers of CD169+ macrophages. … We hypothesize that the initial viral infection may have caused immune-mediated structural changes of the microvasculature, potentially explaining the exercise-dependent fatigue and muscle pain.”

https://actaneurocomms.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40478-023-01662-2

Maybe all post-infectious conditions do this!

Thanks for the info, Ann! I was surprised at the statement, “Viral infections are well-known triggers for a multitude of autoimmune processes.” I didn’t know that viral infections could trigger autoimmunity. But I’m glad to hear of any research being done on post-viral infection issues. It’s certainly much needed research!

Cort, what a super blog this is! it is helping me a lot in trying to figure out what is going on in MECFS. Thanks.

I have a question: although blue indicated, the reference to Dr Miwa 2016 in the following text does not connect to anything. can you write me the reference to the proper paper?

your text: Outside of ME/CFS specialists, most doctors are unaware that this irregularity is even physiologically possible. The basic facts of the RAAS paradox in ME/CFS were described in a paper by Dr. Miwa in 2016, building on his earlier 2014 paper.

Hi Peter, thanks for the kind words about the article. Glad you found it helpful. Here is the Miwa paper: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27401397/

Dear Patrick, thanks for the fast reply. I have two burning question:

(1) you describe/present that the symptoms worsen when having a PEM. are there scientific data on the worsening with PEM (e.g. hyponatremia)?