With so many possibilities, it’s a confusing time. This study, though, proposes an overarching factor has been found.

So many possibilities…Is it the mitochondria? Or the blood vessels? Or the liver? Or plasmalogens? Or viral reactivation? How about viral-induced inflammation? Brainstem dysfunction… It’s both exciting and overwhelming to see so many possibilities show up for long COVID, ME/CFS, and related diseases.

We want the answer and we don’t seem to be getting it. Instead, we seem to getting more in the weeds. Maybe, though, we need to step away a bit. It’s possible that many of these theories are, in fact, correct and that we simply have to find a way to link them together. It’s probably going to take a multi-systemic problem, after all, to produce – in ME/CFS’s case – one of the most functionally disabling diseases known to man.

So maybe the best thing to do is just sit back and watch things reveal themselves. Something interesting certainly revealed itself recently in a long-COVID study which actually may be able to tie things up a bit.

The New York Times offered up its review “Scientists Offer a New Explanation for Long Covid” from Pulitzer Prize winner Pam Belluck. Check out what Belluck’s intro says about the state of long-COVID research.

“This is one of several new studies documenting distinct biological changes in the bodies of people with long Covid — offering important discoveries for a condition that takes many forms and often does not register on standard diagnostic tools like X-rays.”

Things, in other words, are happening…

The Study

The study, “Serotonin reduction in post-acute sequelae of viral infection“, which included about 50 mostly University of Pennsylvania co-authors (plus some heavyweights (Henrich, Deeks, Peluso) from the UCSF LIINC team), made up for in intensity which it lacked in size. As in the recent NIH WASF3 study, once this group uncovered a bone, they really gnawed on it.

That’s new – at least for ME/CFS. We’re seeing research groups with the resources to really chase down their findings take on long COVID and it shows. Both the Hwang group, with its WASF3 finding, and this group with its serotonin finding, for instance, immediately turned to and expanded their findings using mouse studies – something that has almost never been done in ME/CFS. You’ll see this group take a finding, validate it in several ways, and then expand on it. This will happen multiple times. In the end, you get a preliminary but satisfying and, in this case, possibly quite expansive result.

Serotonin is a “feel-good” chemical. Could low levels of it be affecting systems across the body in long COVID and ME/CFS?

While the study was not large (n=110), it was certainly not small by ME/CFS stands. It compared the metabolites (using metabolomics) in the blood of long COVID patients between three months and 22 months after their infection to recovered COVID-19 patients and people who were in the midst of a coronavirus infection.

The main pathway that popped up – the serotonin pathway – was a bit of a surprise. Serotonin was the only significant metabolite that did not recover to pre-infection levels in the long-COVID patients.

Serotonin seems like a new entrée in the “discover what’s causing ME/CFS and long-COVID sweepstakes”, but it’s not really. While serotonin itself has never been a major focus, ME/CFS researchers have been looking into a key part of the serotonin pathway – tryptophan – for quite some time. Plus, low serotonin levels have been found in ME/CFS.

One thing for people with ME/CFS and other post-infectious diseases to note is that because these researchers used a number of pathogens to test their hypotheses, this finding is not necessarily specific to the coronavirus. For instance, they found that infecting mice with the vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) also decreased their plasma serotonin levels, and that after creating a chronic infection with the lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV), the same thing happened.

When they introduced a compound (synthetic double-stranded RNA polyinosinic: polycytidylic acid (poly(I: C)), that mimics a viral infection, serotonin levels dropped as well. Once they stopped providing that compound to the mice, their serotonin levels rebounded.

The Interferon Connection

Since the problem is not necessarily the virus – but the immune response to the virus – next they assessed the levels of the main antiviral cytokine – type 1 interferons (IFN-a/IFN-b) and found that a coronavirus, or other infection, as well as a simulated infection, all “strongly upregulated” interferon-stimulated genes.

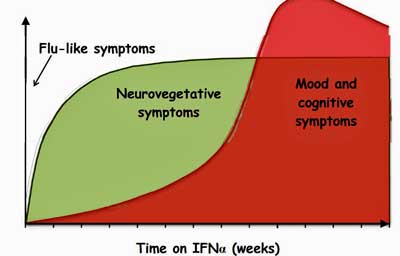

Interferon alpha (IFN-a) – an antiviral factor produced by the body – was used for many years to treat hepatitis C. Its production of severe fatigue in a significant subset of patients helped to open the door for distinguishing “sickness behavior” and the realization that most of the symptoms experienced during an infection are produced by the immune system.

The IFN-a finding also produced a nice template for understanding how sickness behavior is produced and how to manage it. Subsequent studies that examined what’s happening in IFN-a-treated patients, again and again, seemed to have relevance for ME/CFS. That made sense – from the very beginning, it’s been conjectured that people with ME/CFS are simply caught in a sickness behavior loop.

IFN-a increases serotonin turnover in the prefrontal cortex – an area of the brain impacted in ME/CFS. IFN-a administration targets the reward and movement centers of the brain in the basal ganglia – a brain region of interest in ME/CFS – and induces motor slowing – which has been found in ME/CFS. IFN-a administration has also been associated with reductions in another feel-good brain chemical – dopamine. (Serotonin production in the brain occurs in the brainstem – another area of interest in ME/CFS).

Given the carnitine issues that have shown up in ME/CFS recently, it was interesting that IFN plus L-carnitine reduced the fatigue levels. Another study found that Modafinil – a stimulant – was helpful in reducing IFN-a-induced (i.e. inflammation-induced) depression. A gene expression study noted that similar genes were activated in IFN-a-treated patients and people with ME/CFS. Three years ago, London researchers proposed that IFN-a constituted a “novel, inflammation-based, proxy model of chronic fatigue syndrome“.

A nice, robust increase in interferon-associated genes then, makes sense in both long COVID and ME/CFS.

An Interferon-Serotonin Connection

Type 1 interferons – which are implicated in the “sickness behavior” response – downregulate tryptophan absorption in the gut.

Next came the big question – could the interferon activation have had anything to do with the reduced levels of serotonin found? Again they turned to the mice and found that serotonin levels stayed at normal levels in mice that were genetically created not to respond via the interferon pathway to the viral mimic.

Since most of the circulating serotonin in the body is synthesized from tryptophan in the gut, the next question was whether the coronavirus (or another viral infection) might be limiting tryptophan production in the gut. (Tryptophan is the precursor to serotonin.)

THE GIST

- We’re starting to see some really in-depth studies; studies that are able to go beyond initial findings and expand greatly on them. That’s obviously the result of research groups with the resources and time to really track down findings. That’s something we haven’t really had with ME/CFS but do, at times, have with long COVID – and that means things can go much more quickly.

- This is a long and complicated study – so much the better! The 50+ research group used metabolomics to assess what was going on in long COVID and then a bunch of mouse studies to expand on the results.

- Finding that serotonin was the only significant metabolite to be downregulated in long-COVID patients, they infected mice with several different viruses and exposed them to a viral mimic – and found (lo and behold) reduced serotonin levels in them as well.

- That prompted them to assess the main antiviral response in cells – the interferon system – and found evidence that it was highly activated. (See the blog for evidence of interferon upregulation in ME/CFS.) Next, they asked if the activated interferon system might be interfering with the production of the precursor to serotonin – tryptophan. Turning back to the mice, they asked if an infection might be interfering with the production of tryptophan – and it was.

- So far so good…But how was tryptophan being depleted? Turning to the main source of tryptophan in the body – the gut. A gene expression analysis of the intestinal tissues revealed a strong upregulation in genes associated with inflammation and viral infections. “Remarkably”, they stated the gene functions “most significantly diminished” by the viral mimic were involved in nutrient metabolism, including amino acid (tryptophan is an amino acid) absorption; i.e. the infection appeared to have affected the ability of their cells to take up tryptophan, in particular.

- Things were really heating up now. Wondering whether tryptophan supplementation could help, they found that both a special diet (containing a glycine-tryptophan dipeptide) and/or supplementation with the serotonin precursor 5-hydroxytryptophan (5-HTP) returned serotonin levels to normal.

- The authors concluded that “collectively, these data demonstrate that viral-RNA-induced inflammation impairs intestinal tryptophan uptake, which causes systemic serotonin depletion.” Notice that they’re not just talking about the coronavirus…this finding could pertain to all infectious events – which, of course, means it could apply to ME/CFS.

- Next, the manufactured small intestinal “organoids” – miniaturized organs that are derived from stem or tissue cells to study what a simulated viral attack might be doing to the intestinal tissues. Rather remarkably, the organoids responded with a downregulation of the ACE2 receptor – which has been implicated in both long COVID and ME/CFS.

- The ACE2 receptor is associated with the “renin-angiotensin-aldosterone” paradox, which makes it impossible to raise the blood volume in ME/CFS to normal levels but until recently has been mostly ignored. ACE2 dysregulation could, though, also be producing inflammation, whacking the mitochondria, causing fibrosis, inhibiting muscle repair, damaging the endothelial cells lining the blood vessels, producing vasoconstriction (narrowing) in the blood vessels, jacking up oxidative stress levels, reducing the levels of nitric oxide – an important vasodilator, and impacting the gut flora.

- Importantly, this study suggests that any infection might be able to dysregulate the ACE2 receptor – thereby potentially explaining why it’s gotten messed up in ME/CFS.

- The authors also showed how low serotonin levels might be impacting the vagus nerve. The authors turned conservative in the end, proposing that supplementation (5-HTP) and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors might help increase serotonin levels. They are starting to trial to test the effectiveness of fluoxetine (Prozac) and possibly tryptophan.

- Compare that, though, to a 2021 paper focusing on ACE2 dysfunction which proposed using escitalopram, coenzyme Q10, and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide to restore endothelial functioning, suggested trying angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), fat globule membranes (MFGM), b-glucan and metformin to restore gut health, and drugs called senotherapeutics (dasatinib, hyperoside, quercetin, fistein, Navitoclax) to impact cell death and aging.)

- (Although the authors did not mention it, the Epstein-Barr virus – which is commonly reactivated in ME/CFS – has been shown to impact serotonin levels as well.)

- Finally, the authors proposed that serotonin depletion links the four horsemen of the long-COVID apocalypse (viral persistence, chronic inflammation, hypercoagulability, and autonomic dysfunction) together.

- The study garnered a lot of media attention and was well-received by major long-COVID researchers. As many of the results were done in mouse studies, they need to be verified in humans (when possible) and larger studies need to be done. For now, though, the “serotonin surprise” is making waves.

Whence the Tryptophan Deficiency?

Now it was time to chase down the cause of the tryptophan deficiency. Noting reduced levels of tryptophan can be caused by gut problems (reduced absorption) or by having too much tryptophan being converted in kynurenine, they next examined the kynurenine levels in their long-COVID patients and found – to their evident surprise – that they were not elevated.

Once again going the extra mile, they found that even inhibiting kynurenine-producing enzyme levels did not restore serotonin levels; i.e. the tryptophan deficiency was not caused by problems in the kynurenine pathway (as has been proposed in ME/CFS).

They surmised that the origin of the tryptophan and serotonin deficiency, then, must lie in the gut. Thinking that tryptophan/serotonin was simply not being absorbed, they put the mice through a series of dietary tests. Neither putting the mice on a diet, nor feeding them extra supplies of tryptophan (while exposing them to the viral mimic) altered their tryptophan or serotonin levels, indicating that tryptophan absorption in the gut was not the problem. Nor did they find a reduction in serotonin-producing cells in the gut.

Apparently at somewhat of a loss as to what was going on, they turned to the tissues of the small intestine of the mice to try to understand what was going on. A gene expression analysis of those tissues revealed that the mice exposed to the infection mimic demonstrated strong upregulations in genes associated with inflammation and viral infections.

“Remarkably” they stated the gene functions “most significantly diminished” by the viral mimic were involved in nutrient metabolism, including amino acid (tryptophan is an amino acid) absorption; i.e. the infection appeared to have affected the ability of their cells to take up tryptophan in particular. (The gene expression pathway that converts tryptophan into serotonin was not affected: the problem appeared to entirely lie in the inability of the gut tissues to take up tryptophan.)

Next came a fascinating and possibly helpful test. Wondering whether tryptophan supplementation could compensate for the impaired tryptophan uptake, they found that both a special diet (containing a glycine-tryptophan dipeptide) and supplementation with the serotonin precursor 5-hydroxytryptophan (5-HTP) returned serotonin levels to normal.

The authors concluded that “collectively, these data demonstrate that viral-RNA-induced inflammation impairs intestinal tryptophan uptake, which causes systemic serotonin depletion.”

Note that altered tryptophan metabolism has been found recently several times in ME/CFS.

Organoids

They weren’t nearly done yet. This intrepid group’s next step was to use something we’ve never seen before in ME/CFS research – small intestinal “organoids” – to study what a simulated viral attack did to the intestinal tissues.

Organoids are miniaturized and simplified organs that are derived from stem or tissue cells. The organoids, interestingly enough, responded with a downregulation of the ACE2 receptor – which has been implicated in both long COVID and ME/CFS. The analysis implicated the NF-kB transcription factor and the TLR3 receptor it turns on in the interferon response, and found that type 1 interferons reduced the expression of genes involved in tryptophan absorption in the gut.

The ACE2 Tryptophan Link

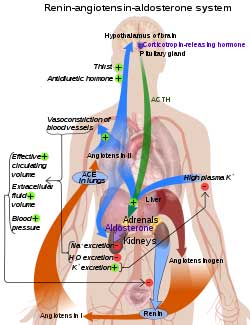

Could low serotonin levels explain the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone paradox in ME/CFS and POTS?

ACE2 is the receptor the coronavirus uses to enter cells. A downregulation of the receptor had been found when the mice were subjected to a simulated viral attack. Several small studies have implicated the ACE2 receptor and the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) in ME/CFS and POTS as well.

Next, the researchers used genetically altered mice to show that downregulation of the ACE2 receptor was associated with a reduction in tryptophan levels. That finding potentially tied together long COVID, ME/CFS and POTS in a very specific way.

From the beginning, it seemed clear the virus would impact the ACE2 receptor in long COVID – it was, after all, how it entered the cell. But what about ME/CFS? What might have caused the receptor to go bonkers in ME/CFS has been a mystery. Now we have a possible cause. It appears that an infection – perhaps any infection – can impair the activity of ACE2 genes.

They also noted that because tryptophan is the precursor for niacin, NAD, and melatonin, those compounds could be impacted as well. Note that each of these has been used in ME/CFS and associated diseases.

The Weird ACE2 Long COVID – ME/CFS Connection

It’s seemed beyond weird that the coronavirus would enter the cells using the same receptor that studies have linked to the renin-aldosterone-paradox in ME/CFS and POTS. ACE2 dysregulation could not only account for the low blood volume in ME/CFS but could also impact many other things (lowered white blood cell counts, impaired oxygen uptake by hemoglobin, increased oxidative stress, leaky gut, problems with lung perfusion, reduced vasodilation of the blood vessels, inflammation, and heart issues).

I’ve been puzzled that the ACE2 situation in ME/CFS has not been addressed more. Until Wirth and Scheibenbogen addressed the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone situation in their hypothesis, it was virtually ignored in ME/CFS circles. Things began to pick up a bit with the coronavirus pandemic, however. A 2021 study failed to find any difference in ACE2 gene expression in ME/CFS and healthy controls, while another found reduced ACE2 expression.

We knew that the coronavirus’s use of the ACE2 receptor could affect it. Except for Miwa’s proposal that the HPA axis, and Wirth and Scheibenbogen’s suggestion of activation of the kallikrein-kinin-system (KKS), we had no explanations for one of the strangest manifestations in ME/CFS – the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone paradox, where the presence of low blood volume fails to kick in the RAAS system to boost it up again.

Now we have a possible answer – any infection may be able to impair ACE2 functioning.

That could be a big deal. In 2021, researchers proposed that the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, that ACE2 is a part of, was producing inflammation, whacking the mitochondria, causing fibrosis, inhibiting muscle repair, damaging the endothelial cells lining the blood vessels, producing vasoconstriction (narrowing) in the blood vessels, jacking up oxidative stress levels, reducing the levels of nitric oxide – an important vasodilator, and causing the gut flora to be thrown off in both ME/CFS and long COVID.

Ignoring the really intriguing connection between ACE2 receptor dysregulation in long COVID, ME/CFS, and POTS, the authors did note that “none of the mechanisms described in this study are unique to SARS-CoV-2 infection“.

Finally, they used mouse studies to show that serotonin depletion could also be responsible for a reduction in vagus nerve functioning and cognitive impairment, and noted that vagus nerve functioning is impaired in chronic fatigue syndrome (yah!).

It was quite a tour de force. Given all the experiments carried out, it wasn’t surprising that this study had 50+ co-authors.

The authors acknowledged that not all long-COVID patients have low serotonin levels, and turned conservative at the end, proposing that supplementation (5-HTP) and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors might help increase serotonin levels. They are starting to trial to test the effectiveness of fluoxetine (Prozac) and possibly tryptophan. While this is going to be a rather crude trial the researchers will be able to see if Prozac increases serotonin metabolite levels and if doing so helps.

(Compare that to the 2021 paper which proposed using escitalopram, coenzyme Q10, and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide to restore endothelial functioning, suggested trying angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), fat globule membranes (MFGM), b-glucan and metformin to restore gut health, and drugs called senotherapeutics (dasatinib, hyperoside, quercetin, fistein, Navitoclax) to impact cell death and aging.)

Again, note that because these researchers used a variety of pathogens as well as simulating a pathogen attack, we know this model is not unique to the coronavirus and could apply to other post-infectious diseases. In fact, the authors proposed it might apply to non-viral conditions such as multiple sclerosis.

Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) Connection?

Epstein-Barr virus wasn’t mentioned, but it too is able to down-regulate serotonin and can affect ACE2 receptor functioning.

One wonders, given the recent association found between multiple sclerosis and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), how long MS will be considered “non-viral”. The authors also missed a magnificent opportunity (in my mind, anyway) to connect EBV with a similar scenario.

EBV can be found in the mucosal lining of the gut and can affect and be affected by the gut microbiome. In 2021, Ohio State University researchers found that Epstein-Barr Virus dUTPase enzyme altered the expression of tryptophan, dopamine, and serotonin metabolism in ME/CFS, and chronic EBV has been associated with increased tryptophan degradation. Interestingly, EBV interacts with the ACE2 receptor as well.

Overarching Finding?

This group got far enough to propose a mechanism that linked the four horsemen of the long-COVID apocalypse (viral persistence, chronic inflammation, hypercoagulability, and autonomic dysfunction) together in a single devastating pathway, and suggested some treatments.

The authors believe low serotonin levels could explain a lot. This study, while impressive, is a beginning, though, not an end. Time will tell…

“All these different hypotheses might be connected through the serotonin pathway,” said Christoph Thaiss, a lead author of the study and an assistant professor of microbiology at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania.

The study made quite a media splash showing up New York Times, Yahoo, Medical News Today, NPR, MSN News, ABC News, etc.

Dr. Michelle Monje, a professor of neurology at Stanford University, said “I’m impressed by the study. I think they did a beautiful job showing the causality of these changes.” Akiko Iwasaki, an immunologist at Yale University, said the story shows a “very nice linear story. Everyone who’s engaged in this research should now be thinking about this serotonin pathway,”

Since a major part of the study involved mouse studies, the results need to be verified in humans and in larger studies. It should also be noted that both Cortene’s work and the Metabolic Trap hypothesis predicted that high not low serotonin levels in the brain were the problem. For now, though, the “serotonin surprise” is making waves.

Health Rising’s Quickie Summer Donation Drive is On!

Health Rising’s Quickie Summer Donation Drive is On!

Long term CFS survivor. About 2 years ago I started using tryptophan for quality sleep. I use quite large does nightly. I have been amazed. It has made a very big difference in my quality of life. Having to do with serotonin?? Likely

+

Thanks, Linda – One thing I was wondering reading this was if enough serotonin or 5 HTP was being taken to get results.

I wasn’t able to tolerate 5 HTP. If I remember correctly, one of the ingredients was methylated, and I can’t do methyls. I buy straight tryptophan.

Hi Linda – can you tell us how large a dose of tryptophan you find works? I’d love to get off Rx sleep meds and it is worth bringing up with my doctor, who’s very open-minded. Did you phase up or start with the large dose you’re taking now. Also (sorry), do you have to take it a certain amount of time before you go to sleep, like an hour or something, or do you just take it “at bedtime”. Thanks!

I started at 1000, worked my way up to 3000. Then I found that change of seasons had an impact, and would occasionally use 5-6000. The doses are WAY more then of the recommended doses of Trudy Scott, who works with amino acids. But, it is working for me, no side effects, and I there isn’t much I wouldn’t do to sleep. I have RX sleep meds, that I use instead, if I am in extreme pain or stress. I take about an hour before bedtime.

Hi Linda , can you have a look at the ingredient you mentioned please? Was the problem the ingredient only or also 5HTP?

It was some year ago, but I remember that I was having a similar response to when I use methylated supplements, so checked the ingredients and one of them was methylated. I simply stopped using it.

I believe it was which ever ingredient was methylated. It was years ago I do not remember what they were.

Hi Linda,

Would you be willing to give more specifics about what improvements you saw?

Just sleeping was awesome after decades of not being able to go into a sound sleep!! Pain levels decreased, brain fog decreased. Ability to think and function increased. Mood improved substantially.

Cort! Now, I like this tidbit because it follows along with some thoughts I’ve had. I remember and can recite the endocrine response to shock. As a medic, shock has always been a concern, but there are a plethora of causes. Of course, one of our biggest concerns was ecxanguation, but there are numerous other causes of low blood volume other than bleeding. Obviously, fluid administration is a starting point…but, as my thoughts have gone, what if sufferers of ME/CFS and ortho intolerances are suffering with low blood volume? Well, we take an Alpha positive agent and shrink the tank…Midodrine, for example, then when we lie down we blow the top of our head off. I guess we could walk around with a liter IV bag and a macro drip. Obviously we can’t change the rennin/ angiotensen curve and mast cell production, aldosterone, and all those ductless gland secretions. And just how the hell does a gland secreet without a duct anyway? And the mention of tryptophan just makes me sleepy.

But with my decent, but limited knowledge of A&P, what they’re saying makes a bunch of sense. I’m glad they mentioned Oxidative Stress which has been on my mind since I read the little known of Spanish study.

By George, I think they’re onto something here!

May I ask how much tryptophan is needed for you to get better quality sleep? ‘quite large doses’ is a little vague – is there a study you would point me to where your dosage comes from?

I think a log of my symptoms would be improved just from getting better sleep (I currently am up 6-10 times a night, and go right back to sleep, but when I have a few longer sleep segments at night (1:30 to 3:00 hours), I am better the next day.

Since I got sick (CFS/FM/ME) in the mid 90’s, I never went into a sound sleep. My ability to think and function was affected. My IQ seriously dropped. It also contributed to an increase in my pain levels, from tossing and turning all night. My mood has definitely improved. Not sure if it is directly related to the serotonin or the quality of sleep. I have come to believe that the quality of sleep is a major player in the quality of our lives. The tryptophan dose list as 500-1000 mg. The specialist that I was following has her patients play with the dose, up or down, until they find what works for them. I worked up to 3000 mg and was sleeping. Due to life and stress, I did need to increase that dose to 5000 mg. Hoping I can decrease back to my base dose when things calm down. I sleep now, soundly and wake refreshed.

Thank you, Linda. That is a big dose to end up at – but not too huge a place to start. I think I remember taking 500mg of tryptophan somewhere back, I think BEFORE I got sick (<1989), but I can't remember why. Maybe sleep.

IIRC, it wasn't too expensive, so reasonable to try. But I don't think I got a significant response then – but I don't believe I went over the 500mg, either.

For some reason, this serotonin surprise post has hit some of the markers I expect or want for a solution (reasonable price, as available as the viruses that may cause us to need it, explains a lot of symptoms, etc.). I may try it, and will check into getting Prozac or equivalent from my primary, off label, to see if it helps. I'm skittish, so may also wait until they do human trials for any large amounts.

Start small and keep increasing until you find the dose that works for you i would NEVER start anything at a large dose. My system is just too weird!

Linda………….that is fantastic that tryptophan has helped. Which brand do you take?

Just source natural. I can get it from amazon or walmart on line

Sounds like me. CFS/ME from age 30 to current at 84. Best wishes. SM

Wow Sanmag. 54 years! Around 1969. What a long strange trip its been. Hopefully others will not have to endure this for so long.

I experimented with 5-HTP a while back and couldn’t tolerate it, so concluded (I don’t know if correctly) that my serotonin levels were high. I was wary of developing Serotonin Syndrome so stopped taking it. Incidentally, it improved some of my gastrointestinal symptoms, reinforcing the fact that serotonin is produced in the gut. It didn’t help me with sleep.

I was not able to tolerate the 5-htp either. Looking deeply into the ingredients, I found that one of them was methylated. I can not tolerate methyls. You might check into that. I have digestive issues, but the tryptophan made no difference in that area. (that I am aware of)

Cort, how is serotonin measured? You said, in the plasma? Does that reference serotonin behind the blood-brain barrier in the CNS?

I don’t believe that it refers to serotonin in the CNS. The reason I don’t believer that it does is that I read that serotonin in the CNS is produced in the brainstem – which is its own can of worms in ME/CFS.

Isn’t is true that serotonin is mostly produced in the gut? And wasn’t low serotonin not a paradox in ME/CFS? If i remember correctly. I think it is just like you said a part op the problem not the cause. But it is old school to me… 🙂

They must look at all neurotransmitters, catecholamines and hormones. Wouldn”t that be something…..

In the central nervous system its produced in the brainstem; otherwise, I think its all in the gut.

I’m late to this party, but I wanted to offer my experience after reading the “Serotonin Surprise” article. I’ve had fibromyalgia for 19 years and ME/CFS for 17 years.

I got COVID in September 2022, and I recovered in every way I’m aware of except my cognitive function. My already compromised brain wasn’t the same after COVID, and in recent months it seemed to me to have gotten much, much worse.

After reading the article, I sent it to my doctor and asked for a script for Prozac. He wanted me to try 5-HTP first, and said to take 100 mg. I got some Natrol 100 mg, time released 5-HTP, and I took one the afternoon they arrived and another when I went to sleep. I was amazed that the clamp on my brain seemed to have let go. And perhaps even more amazing to me was that I woke up without my usual morning aches and pains. I’ve tried taking only 100 mg, and that doesn’t seem to give me as noticeable results.

Yes, we’re all different, and we each have to find our own way. I’m just profoundly grateful that this article came along when it did. I was starting to panic that I would have to be put into a nursing home at age 71.

Also connected to fibromyalgia? https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8068842/

And here – with estrogen (!)

An Association of Serotonin with Pain Disorders and Its Modulation by Estrogens

One of the most studied neurotransmitters related to pain disorders is serotonin. Estrogen can modify serotonin synthesis and metabolism, promoting a general increase in its tonic effects. Studies evaluating the relationship between serotonin and disorders such as irritable bowel syndrome, fibromyalgia, migraine, and other types of headache suggest a clear impact of this neurotransmitter, thereby increasing the interest in serotonin as a possible future therapeutic target.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31731606/

Thanks for the estrogen connection Cort!

Doxepin also increases serotonin in the brain. My brain fog has gone away since I started it. But I still get monthly relapses, so I’m hoping to try estrogen supplementation next month. It’s good to see the connection.

How about that – the mast cell inhibitor also increases serotonin levels in the brain. Good luck.

I was waiting for this to be revisited in MECFS-FMS post-infection research. I am a 52 yo female in post menopause. While increasing estrogen (HRT) and becoming estrogen dominant like in perimenopause, I found my symptoms (similar) to ‘serotonin toxicity” come back. I have a mild MAOA mutation, which affects the breakdown of serotonin. Too high? too low? This research is getting somewhere!

Depression Question:

Are there reports or anecdotes that show people with ME/CFS being prescribed Prozac for their depression, and then reporting considerable improvement in their ME/CFS? (Beyond the measure of improvement a person without ME/CFS would expect as a result of going on Prozac.)

Good question, Brian. I’ll be interested in the responses….

I have had CFS since 1976. My CFS symptoms disappeared in 1994 after being prescribed an SSRI antidepressant (Paxil.) The symptoms stayed gone as long as I continued taking Paxil, until 2018, when the CFS symptoms returned. In 2018, I tried several different antidepressants until I got relief again with Effexor. That remission lasted until 2022 when I contracted Covid. My CFS symptoms are no longer responding to antidepressants, but I am certain there is a relationship between serotonin and ME/CFS. Taking antidepressants gave me 28 years of remission from CFS symptoms.

Me too. I took lexapro. 16 years remission. When i stopped due to other issues the cfs came back in full force. I will try lexapro again soon. But i developed severe tinnitus. So afraid to take it again, but i will try

Agree. Fluoxetine has been a major part of me being able to live a semi-normal life with CFS over the last 25 years. And I have always thought it was much more than its antidepressant effect.

It should also be noted that fluoxetine has some anti-inflammatory effects, and reduces certain inflammatory cytokines.

Tryptophan supplementation: be careful with the potentially lethal Eosinophilia–myalgia syndrome:

a rare, sometimes fatal neurological condition linked to the ingestion of the dietary supplement L-tryptophan. The risk of developing EMS increases with larger doses of tryptophan and increasing age. Some research suggests that certain genetic polymorphisms may be related to the development of EMS. The presence of eosinophilia is a core feature of EMS, along with unusually severe myalgia (muscle pain).

Wikipedia

Inflammation caused depression is not uncommon at all. If memory serves it might be around 40% or something like that. In a disease in which just about everyone believes has an inflammation component – inflammation caused depression might be expected I would think.

I used it too. It didn’t help me. I am a severe ME patiënt. I know that people with a burnout or are stressed respond good on SSRI’s. But anyway good to see it helps people.

I think a big question is whether people like yourself with severe CFS have the same illness as someone like me who had moderate CFS, which has been mild now for a long time. Is it different severity on a spectrum of the same illness, or are they potentially different illnesses?

Many years ago Prozac was all the rage for CFS but it eventually proved disappointing.

This is where the approach falls down for me at least on the treatment end. I think we would know by now if Prozac was really helpful in ME/CFS. If low serotonin is a problem there must be more to it than that.

Agreed

I agree Cort. Considering that so many doctors think that M.E. is a depressive disorder, you’d think there would have been loads of patients recovering after being prescribed Prozac.

Maybe there have been but we don’t hear about them much? As I say above, it has really really helped me over the past 25 years, especially with fatigue, and I definitely have CFS ( I get moderately bad PEM). I imagine many or most people who get much better don’t tend to hang out so much on these sorts of websites.

Matthias, does it interfere with your sleep? I tried one of the SSRIs early in my CFS and had more trouble sleeping. I think it was Paxil I tried.

Not really, maybe a little when I first went on it.

thanks

Most Antidepressants are metabolized in the liver by one specific liver enzyme (I forget offhand which one). Some people can be a fast or slow metabolizer based on mutations of this enzyme. This can mean they get more side effects, a paradoxical response, a non therapeutic response etc. There is genetic testing from Genesight for this.

No antidepressant ever helped me with pain or fatigue or sleep. But I am a rapid metabolizer based on gene testing.

That is fascinating! I hope everyone sees your response to my question, not just me.

Thank you so much for sending all that information!

Exactly! Pretty sure every single ME/CFS

Patient suffering mild, moderate to severe symptoms has tried at least one SSRI at some point in their desperate search to feel any relief.

Of course serotonin is out of whack. What isn’t?? More info to compile into a massive mound of shrugs. I always say info and data are useful, so appreciate their work.

Qu’en est-il des personnes SFC qui ont un excès de sérotonine ? En 2021, j’ai fait un test qui a révélé que mon taux de sérotonine était élevé.

D’après le docteur Mercola, un excès de sérotonine peut causer des problèmes importants. Je ne peux pas retrouver l’article exact, mais si je me souviens bien, il mentionne un lien entre la sérotonine et la progestérone. Trop de sérotonine peut être la cause d’un excès d’œstrogène (ou l’inverse?) et un faible taux de progestérone.

Dans le même article, il dit que pour lutter contre la dépression, l’anxiété et les problèmes de sommeil, prendre 100 mg de GABA suffirait à réduire les symptômes et faire baisser le taux d’oestrogène…

What about CFS people who have excess serotonin? In 2021, I took a test which revealed that my serotonin levels were high.

According to Dr. Mercola, excess serotonin can cause significant problems. I can’t find the exact article, but if I remember correctly it mentions a connection between serotonin and progesterone. Too much serotonin can be the cause of excess estrogen (or the opposite?) and low progesterone levels.

In the same article, he says that to combat depression, anxiety and sleep problems, taking 100 mg of GABA would be enough to reduce symptoms and lower estrogen levels…

Interesting! Many articles state that estrogen dominance (low estradiol/progesterone ratio) is linked to elevated serotonin. Progesterone increases GABA and balances (lowers) estrogen. I could be wrong, but I think there is an hormonal and genetic (MAOA) link, which would affect men at a lesser degree as well. Our food is full of xenoestrogens.

Yes – both Cortene’s and the Metabolic Trap hypothesis predict high serotonin levels in the brain and Cortene has a positive small study to back up their claims. (They don’t measure serotonin, though)

I’ve had ME/CFS and fibromyalgia for nearly 40 years. I tried Prozac years ago but it made me very drowsy. I’ve had bad side effects with most antidepressants but I’ve been on 50 mg doxepin for many years. It helps me get a good night’s sleep and has fewer side effects. It also helps with my mild depression. But it hasn’t done a thing for my chronic pain and fatigue. So, there is probably a connection with serotonin and some improvement in symptoms but it’s unlikely to be the answer to solving ME/CFS and long COVID.

How is you diet? Did you try anti inflamatory? Lower oxalates in diet help us immensely.

I never tried a low-oxalate diet but it seems to restrict a lot of foods. My diet is fairly healthy. I don’t eat any fast food but I do eat quite a bit of processed food. That’s because I’m older and single and cooking is just too exhausting. I also live in an apartment and have no dishwasher, so the less dishes I have to wash, the better! So, diet and also exercise are two areas that I could improve on (in a perfect world), but I’ve been sick for so long and I’d consider my ME/CFS and fibromyalgia moderately severe, so I do the best I can. I know it’s a bit lazy but I’m just hoping for that miracle cure, which is highly unlikely given that I’m 70 years old now!

@NancyA. Did the doxepin help with brain fog? Thank you.

Unfortunately, no….and as I’ve gotten older, the brain fog just seems to get worse. I no longer drive and am mostly homebound these days. The doxepin helps a lot with being able to stay asleep for most of the night, except for one trip to the bathroom in the middle of the night. I’m on a low dose but it still helps with depression and anxiety.

Yes I was prescribed it in my first year (early 90s) on basis of psychosocial model, it just made me worse. I haven’t been able to tolerate any SSRI’s only tricyclics, but no antidepressant has improved my ME only helped with sleep and anxiety. I also tried tryptophan early on, no help.

My family member with ME/CFS had depression and was being treated with Fluoxetine when she developed ME/CFS. She has continued to take Fluoxetine, and her ME/CFS has continued to get worse, now severe.

Cort,

I’m too severe now to do my own research. Could you kindly comment on how these findings might relate to Phair’s metabolic trap tryptophan hypothesis?

I have been taking Prozac and amitryptiline for depression and to sleep better (amitryptiline) and it never, ever influenced my ME.

I do remember that Nijmegen put out a Prozac study in the 90’s, saying it was so helpful in ME/CFS.

It lifted my depression and enhanced the quality of my sleep, but my ME did not improve one ounce.

The clearer it got that the low serotonin hypotheis in depression was without support the more important seems its role in any other disease.

Perhaps that can pry explain the october slide

This is strange. Earlier hypothesis has been that serotonin levels are too high are dopamine low in CFS. I have low dopamine levels but supplements that boost serotonin make me feel worse.

That is correct! For me the same.

My memory is hazy but I thought Ron Davis warned against taking Tryptophan as a supplement when explaining his Metabolic Trap hypothesis. Does anyone else remember that?

As I understood his “warning” was that you should not really rely on hypothesises for treatment before it is proven. Because it is not safe to do so. Some things are not dangerous, some are. And most people really do not know. He says that about almost everything at every symposium I’ve listened to. It’s only research at the moment.

yes, in a 2019 patient symposium he earnestly advised attendees not to self-medicate based on the (other new, unrelated) information he was about to share. He described how, as a result of earlier research about tryptophan he’d discussed publicly, several patients rushed out to supplement with it, only to report significant worsening of their condition as a result.

However, it’s not clear that those who responded well to tryptophan would necessarily report back, so it might be the same sort of thing we so often see in ME/CFS where a potential treatment works great for some people and does nothing or worsens condition for others…

Well that is a big dose! Myself and friend have tried tryptophan if we get over 1000 mg, we feel like we can’t breathe like we’re going to forget to breathe it’s kind of a scary feeling.

I´d be quite careful here. This clearly is one of those apple-and-oranges PASC studies that we usually are quite critical of, for a reason. Their analysis covers a broad range of PASC phenotypes with a preponderance of previously hospitalized patients. Fact is: from this study we do not have any information how serotonin levels may look like in the PASC phenotype of our interest – namely ME/CFS. They do refer to the longitudinal UNCOVR cohort, in which *no* serotonin reduction was observed in the PASC patients. Makes you wonder if all is indeed about patient selection, doesn´t it?

So really, what we still do not know is if serotonin levels are indeed correlated with, predictive of or clinically relevant in the ME/CFS subtype of Long Covid.

The same holds true for persistently high levels of type I interferons in the blood. Cort, you may have a better overview of the data but I do not think that elevated interferon levels are a consistent hallmark of ME/CFS (or we should urgently find out, especially comparing levels during good and bad days, which I think has never been done but should if one postulates that type 1 interferons may mediate sickness behavior…).

Really I think with this study the gap of unknowing just widened.

What we also know is that any hypothesis of ME/CFS should be able to explain its central hallmark, PEM, right? Could their explanations shed any light here? A sudden drop in serotonin levels after exercise? Mediated by exercise-induced reduced tryptophan uptake? Hmmm – doesn´t sound super plausible to me – but could easily be measured.

So before we have more specific data we should not overinterpret this study but hope for more specific analyses.

Agreed it is a study of one pathway that explains low serotonin levels during an acute infection. To see if this pathway bares any relevance to LC or ME/CFS you have to analyse whether the type I IFN response is really happening in these patients (most studies don’t see this happening) or whether there is a persistent virus (there was no intricate stool analysis).

In an earlier blog post, Cort had discussed the kynurenine pathway in some detail, which might or might not link this to Phair’s metabolic trap hypothesis. But I think the logic that links them would require HIGH serotonin, not low serotonin. There are very clearly some processes at play here that are highly relevant, but I agree with Cort the main point of interest here is that we are starting to have enough information for kinda straightforward explanations that implicate complex multisystem failures.

https://www.healthrising.org/blog/2023/01/07/kynurenine-chronic-fatigue-fibromyalgia-long-covid/

It’s also worth noting that the serotonin study did some very nice analysis of LC patients and a latent class analysis revealed eight LC subtypes of which three have the kind of persistent fatigue we patients tend to associate with our conditions / PEM. If you have the time and brain, it’s worth a read, I thought their design was very nice.

(I should add the only part that I think isn’t great is that they are using a pair of models of general post-viral infection, one of which I think is kind of weird and maybe not as generalizable as they say it is, but overall they’re very limited in comparing their results directly to ME/CFS – only one mention in the whole paper, I think.)

I wonder if the UK genetic study [DecodeME – genome-wide association study (GWAS)] may help with this type of claim – serotonin levels? Basically if there is a large proportion of people with ME/CFS, who have a particular disease pathology (serotonin), then there should be a related genetic (GWAS) signal?

DecodeME – genetic results should be published next year?

Lessons from Dementia were that a number of large GWAS studies were required to identify relevant genes – that’s 3X DecodeME(?). So perhaps NIH could also run a ME GWAS? Chris Ponting is talking at the NIH genetic (roadmap) webinar on 1st November.

DecodeME recruitment phase closes on 15th of November 2023.

It will be good to get nice ME/cFS cohorts identified in these studies. One of the cohorts used was the LIINC cohort which I believe is mostly non-hospitalized patients but will obviously contain some non ME/CFS patients. (On the other hand the results of the LIINC studies seem pretty ME/cFS-ey).

I think the data with regard to IFN in ME/CFS is mixed. Montoya’s exercise study found that it was one of the most discriminatory cytokines post-exercise.

I don’t believe that type I IFN’s are measured all that much. (Usually its IFN-y and associations have been made with it several times). Hanson’s recent study, though, did not find any associations with type I IFN’s.

I don’t think there’s that much on it.

I did miss one interesting study. It was a rodent study from 2006 which used the same viral mimic and it produced the same results but got into the serotonin receptors.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17192569/

In this article, using the immunologically induced fatigue model, which was achieved by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of synthetic double-stranded RNAs, polyriboinosinic: polyribocytidylic acid (poly I:C) in rats, we show an involvement of brain interferon-alpha (IFN-alpha) and serotonin (5-HT) transporter (5-HTT) in the central mechanisms of fatigue.

In the poly I:C-induced fatigue rats, expression of IFN-alpha and 5-HTT increased, while extracellular concentration of 5-HT in the medial prefrontal cortex decreased, probably on account of the enhanced expression of 5-HTT.

Since the poly I:C-induced reduction of the running wheel activity was attenuated by a 5-HT(1A) receptor agonist, but not by 5-HT(2), 5-HT(3), or dopamine D(3) receptor agonists, it is suggested that the decrease in 5-HT actions on 5-HT(1A) receptors may at least partly contribute to the poly I:C-induced fatigue.

A small 1994 exercise study did not find any alterations.

Highly agree – bulk of this is done in mouse models, NOT people, we have some samples to agree but long COVID in a much earlier timeframe post initial infection which we don’t have in ME/CFS. I would suspect any disturbances in serotonin that we see in post-infectious illnesses or FM are all byproducts of other issues from messed up inflammatory responses like they are suggesting here, but just trying to treat with SSRIs has never worked for ME/CFS or FM so I doubt it will do much in long COVID either, on its own, without trying to fix the other disturbances. And without knowing the actual cause you are once again playing whack-a-mole to the various symptomatic manifestations — oh serotonin is messed up, let’s just try to fix that but what about the 20 other things now out of balance, too? In my view a reason this is making such a big splash in long COVID is because no one is trying to imply these people are all just experiencing a psychosomatic illness or are depressed like they did for ME/CFS and FM for so long, so I think the medical community views the disruptions in neurotransmitters as concrete biomarkers to try to treat here more than in other illnesses, where SSRIs/SNRIs aren’t given as much because of deficient levels but because people are “depressed” and coincidentally maybe those would help with fatigue and pain levels, too.

I agree – and I think that a lot of people agree – that this is a multisystemic disease that is going to require several inputs. It will be interesting to see if Prozac or 5-Htp increases serotonin levels or not and if it does – if it does anything and in which people.

The thing that caught my eye with this study, though, is how they just kept digging away and kept getting results.

I would be interested to see how these results can be linked with the study identifying 4 subgroups of ME/CFS (as determined by Dr Alain Moreau, based on the miRNA abnormalities). Those 4 groups also partly explain why treatments / supplements aren’t producing constant results in different persons.

I have a similar story: cfs in remission for 16 years on the SSRI Lexapro. Developed tinnitis. Stopped Lexapro to see if there was a correlation. Still have tinnitus after stopping. When i stoppped the SSRI, all the cfs problems came back in full force. To me it seems like there is a relation between SSRI and remission. Next week i will go to my GP and start lexapro again. Cfs is much worse than tinnitus to me.

So if IFN a is trending high as an overreaction to virus, how about a jak stat inhibitor to bring IFN a down? That should correct the serotonin. Also, magic mushrooms raise serotonin via same mechanism as ssris. Possibly micro or macro dosing might help? Where it’s legal etc

Ssri’s dont always touch on the same 5htp receptors. For me: prozac didnt work, lexapro works great. Seems much more nuanced than we would like it to be. Btw i have no depression or anxiety that could explain Ssri meds to work. So there is -for me- something else going on.

Thanks Cort! Nice clear write up. Cross reference also Van Elzakker’s 2013 hypothesis paper proposing that ME/CFS is an EBV infection of the afferent sensory vagus nerve:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0306987713002752?via%3Dihub&fbclid=IwAR1y_t05BBWuFDlQBD7F1X6RRB8QfTspPI_2qhre8JxBgt69x4EZDZLeb9I

apparently lyme spirochetes can give some false positive EBV in a test

link to article

https://danielcameronmd.com/lyme-disease-causes-positive-test-mononucleosis/

interesting, thanks 🙂 apparently EBV reactivation is a regular thing in COVID19, MS and even pregnancy – https://www.ajog.org/article/S0002-9378(09)01608-1/fulltext – that could be causing the false positives.

When I take any substance that raises serotonin the Restless Leg gets terrible. For me anyway, I suspect low dopamine, not low serotonin. But perhaps it’s more about the balance of the two? A clue might be for those of us that have RLS, raising dopamine might be a better choice. And for those that can tolerate compounds that raise serotonin and do not suffer from RLS, it may indicate that five HTP might be worth a try?

There is the Cortene and Metabolic Trap hypothesis that serotonin is increased not lowered. As always, though, we see lots of differing responses…

Really great journalism here Cort. I’m blown away by the quality of your summaries these days, especially with something this complicated. The Ace2 finding is super interesting and provides an interesting potential ‘starting point’ to explain the vasoconstriction feedback loop of me/cfs. Basically the body compensates for low blood volume by starving the tissues for blood pressure and oxygen. Thanks for all your hard work.

Thanks! I loved seeing ACE2 unexpectedly pop up like that. That really got me going 🙂

So many divergent experiences with serotonin! I couldn’t sleep, felt constantly nervous and lost lots of weight when I tried small doses of Prozac. Paxil made me suicidal. Tramadol, for pain, (which amends serotonin levels) has been ineffective and has caused extreme disassociation. Microdosing Abilify resulted in super brain fog. Other antidepressants have not been helpful and have only made me feel ‘weird’ rather than better. Dozens of supplement trials have only had subtle to no noticeable effect. (TUDCA, as per a previous blog, has just been ordered and I’ll see how that goes…)

The only medication mentioned that has helped is Modafinil. I get about 5 hours of ‘reasonable’ energy after I take it but hesitate to take an additional daily dose as it disrupts sleep.

I don’t always fit the research characteristics of ME/CFS (blood volume, cortisol etc.) either, but do have distinct PEM. The more I delve into the research, the more I think that each individual has to find their own way and there probably won’t be a silver bullet.

Of all my other efforts to ameliorate my disease, small moments of pleasure and happiness, where ever I can find them, are one of my most effective treatments–even if they are fleeting.

ABILIFY CREATED TARDIFF DYSC. WHICH HAS NO CURE AND WILL REAR ITS UGLY HEAD INSTANTLY AND UNEXPECTEDLY WHEN I GET STRESSED OR EXTREMELY DEPRESSED (DEATH IN A FAMILY). THIS RESULTS IN SEVERE MOVEMENTS OF MY HEAD, LEGS AND I FALL DOWN. MY EXTERIOR AND INTERIOR BODY TREMORS’. I BELIEVE AFTER MANY LAWSUITS IT HAS BEEN REMOVED FROM THE MARKET. I SIGNED UP FOR RESEARCH AT SIMMON RESEARCH AND MAYO CLINIC FOR TRIAL EXPERIMENTS’. YOU CAN REGISTER ONLINE ON THEIR WEBSITES. THEY INCLUDE LONG COVID, CHRONIC FATIGUE, MECFS, WHICH ARE ALL CONNECTED. I AM BED RIDDEN 70% OF THE DAY WITH SEVERE PAIN THROUGHOUT MY ENTIRE BODY. GOOD LUCK ACHIEVING HEALTH.

Sorry to hear about your troubles, Laura! I had not heard about Tarkive but I see that is a possible side-effect – https://www.abilify.com/ – very sorry to hear that it affected you. Abilify is still on the market, though, and some people with ME/CFS have found that it helped.

@Laura,

Gee, I’m also very sorry you developed this nasty side effect from Abilify. Always and never are words of the Gods. I pray that ‘always’ won’t be forever for you.

When I get a bad reaction from a medication, I stop taking it. This idea of ‘you’ll get used to it’ almost always isn’t true for me. Dr. Bonilla wanted me to continue with Abilify, and suggested I take it for a year! I refused. Sometimes I think my stubbornness has saved me from consequences like yours. You have my prayers for some sort of reprieve.

I tried SSRIs when I had ME/CFS and it made no difference to my fatigue.

I am really not sure if relevant (but tied to) – according to this functional medicine doctor…..In brief, if the Lipopolysaccharides (LPS) in your gut are out of wack then this prevents the anti depressant meds getting to it’s intended place – much easier explained by the doctor himself in this easy to understand short video (he draws great pictures) video https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d4Q8M6rtfT0serotonin . The actual study he is referencing is this https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34083254/ . Hence I too am disappointed that the study while fascinating and hits a nerve with what I think my son’s issues are, doesn’t get to the root cause. But maybe will. (he has been on sertraline 100mg for over a year and has not made any difference to his physical or cognitive ME/CFS LC symptoms.

At least for me me/cfs and long covid are the same thing. I completely believe the idea that it is post viral(or different types including covid) causing the chaos we all know. I got very severe me/cfs in 2015 for 3 years completely bed bound and unable to talk for 18 months at one stage and never knew why except for doctors saying they though early bloods tests indicated I might have just had a virus. In 2018 I started improving and over 12 months I completely recovered Jane was able to do light exercise again. I had open heart surgery in 2021 and recovered well. Then a week after I had recovered from a mild bout of covid I became bed bound again and am still house bound. At least for me they are one illness used by specific post viral body responses.

Would Niacin, in high dosages, be a potential treatment? This would stimulate negative feeback in the Kynurenine pathway and redirect Tryptophan to more Serotonin?

I find this very interesting especially regarding the ACE2 receptor. I have just checked my 23andme results and I find that I am heterozygous for all 3 quoted so definitely my ACE2 enzyme would be under functioning.

My illness started in 1979 after 2 weeks of what I thought was flu and the main symptoms hit me about 2 weeks after I was trying to recover but had zero energy. I did improve my energy over time but persistent symptoms would appear of severe vertigo and migraines and when the menopause hit that was it and I was into full blown ME. I am lucky in that an oxygen concentrator helps me to put back some energy as I use it 3 times daily and I also benefit from a low dose steroid and thyroid medication so I am not as severely affected as some but still my life is hugely diminished compared with the average person.

I forgot to add that my migraines do respond very well to sumatriptan which acts partly on a serotonin receptor I believe but the only problem is that I get rebound migraines from it so cannot use if more than twice a week.

I am waiting to try a Gepant once my local health authority agree here in the UK to see if a CGRP medication will give me more help.

I am not sure if this adds anything regarding how Sumatriptan works but I copied this from the NHS website?

Sumatriptan works on the serotonin (or 5-HT) receptors located on blood vessels in your brain. This causes them to narrow. This helps take away the headache and eases other symptoms such as feeling or being sick and sensitivity to light and sound.

There are some important cautionary notes on tryptophan supplements in the ME-Pedia. “Dr. Ron Davis, speaking about tryptophan being available on the market, has made it clear that self experimentation can be very dangerous.”

It links to this video where Ron outlines the concerns: https://youtu.be/pFzOrknOylA?list=PLl4AfLZNZEQPxjqF4ojAO3wdCFMeriNBK&t=663

I’m seeing some success stories with SSRI’s with CFS here and other places. I personally think CFS is not its not serotonin issue but an inflammation issue. I think SSRI’s work because they are anti inflammatory. Post viral or gut issues are inflammatory.

That would be my opinion too

Where the hell are Dejuergen and Issie when ya need someone with epic biology knowledge to put their spin on things?

I feel like the most insteresting part of this research is the ACE2 and small instestine stuff. If we can compensate for the shortage there, wouldn’t it go some way to relieving many symptoms? IE, they should be looking at how to treat this locally, rather than just messing around randomly with drugs that affect serotonin. Can we get details of the diet they gave to the mice in the experiments?

I have taken 5htp for about 11 of the 12 years I had ME/CFS. For the first 8 years it was only 15mg at night but the last 3 or 4 I went up to 100mg. It was a game changer for me in many ways. Improved sleep, gut motility, pain, blood pressure and just a better sense of wellbeing.

However, the brand I used stopped working. It had an expiry date in 2021. I thought at the time it was because they changed to slow release it didn’t work. Felt like a missed dose. So I switched to a new brand which worked but when I bought a new bottle with a new expiry date it stopped working. I have since tried around 30 brands. Any brand aside from 1 works great as long as its expiry date is 2021 or before. Product that expired 6 years ago still works great. Most brands stopped working somewhere with an expiry in 2022. There are a couple brands that work with a 2023 expiry date and nothing works with 2024 date or later I have found.

The 5htp raw material is extracted from the griffonia seed only grown wild in Africa and I suspect all manufacturers buy from the same source and there is either a change/problem with the extraction process or seed.

I have reached out to every manufacturer but none will be forthcoming or helpful in identifying what has changed. They all say their product is the best. They suggest something must have changed in me and its not their product. I ask them to explain then how I can still take and expired bottle of theirs and its fine but the new one is like a missed dose. This is when they stop emailing.

Its very frustrating but worse when I say it feels like I missed a dose it feels like withdrawals from hard drugs which gets worse each day. I shake, break out in sweats, unable to eat, pain etc. Its unlivable and thats only day one of withdrawals. I have been lucky enough to locate expired bottle so I don’t have to find out what day 2 feels like. But its becoming harder and harder to find. I had patients from all over Canada send me their unused bottle to keep me going for the last 2 years.

As I write this I only have 6 days of known good 5htp and after that I don’t know what I will do or if I will survive the withdrawals.

Have you measured your serotonin and 5-HIAA levels while taking the newer supplement to see if the 5-HTP is actually working?

I’ve taken 5-HTP for over a decade, and recently measured my urinary neurotransmitters. My serotonin and 5-HIAA were through the roof, five times higher than top of the normal range. As a result, I dropped my nightly dose from 100mg to 50mg and will measure again.

I haven’t noticed any difference in my symptoms, which makes me wonder if I should be taking the supplement at all. It helped me when I slowly weaned off temazepam 14 years ago. But with the test results as high as they are, maybe low serotonin isn’t an issue now.

No I have not had 5-HIAA tested recently and never serotonin levels tested. I remember testing years ago and at only 15mg at night the 5-HIAA levels were quite high but corresponded to the 15mg taken so was not a concern.

For me even dropping 50mg at night I will have major withdrawals the next day and if I repeat that, the second morning will be worse and equal to the feeling as if I missed the entire 100mg dose all together.

Have you tried or considered doxepin? I took it for about a year. But over time, I had to slowly dial back the nightly dose bit by bit because of side effects like excessive daytime sleepiness. Modafinal helped with that, but now it gives me severe headaches resembling migraines.

Anyway, I dialed back the doxepin to where I was taking only one drop of it in a small glass of water each night so I could wake up in the morning without feeling drugged. By that point, it wasn’t really helping and it was easier to just stop taking it and switch to supplements like 5-HTP. But when I did take it in higher doses, I had better sleep and less fibro pain. Too bad it made me too dopey to do things safely like cook and drive.

5-HTP helped me for awhile. Then I watched the “Living From Inspiration” summit online, the one Cort posted about here. One of the speakers said to try methylene blue, so I did.

It works better than 5-HTP. It’s an MAOI, monoamine oxidase inhibitor, like 5-HTP, but stronger. In fact, you CANNOT take them both at the same time or you risk a serotonin crisis, which is life threatening. You need a washout period when you quit 5-HTP of two weeks, then you can begin MB. You also cannot take any other MAOI’s. This stuff is strong.

Read about it here:

https://nootropicsexpert.com/methylene-blue/

Buy lozenges here:

https://troscriptions.com/products/bluecannatine?selling_plan=10867671260

Have you tried methylene blue? It works like 5-HTP but better. See my post below.

I mean, above.

Have you tried pure encapsulations brand? They state to be the top of quality control.

Pureencapsulations.com

Yup….I tried it and it is one with an earlier date when it stopped working. Jan 2022.

I’ve gone as far as having it compounded at the pharmacy at a cost of $150 for only a month supply. It had a 2024 date on the raw extract. It did not work. But an old cheap natural factors from 2017 works great.

This change has affected all brands high and low end alike.

𝐂𝐚𝐮𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐟𝐨𝐫 𝐩𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐬 𝐰𝐢𝐭𝐡 𝐌𝐄/𝐂𝐅𝐒 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐋𝐨𝐧𝐠 𝐂𝐎𝐕𝐈𝐃 𝐚𝐟𝐭𝐞𝐫 𝐫𝐞𝐬𝐮𝐥𝐭𝐬 𝐨𝐟 𝐚 𝐧𝐞𝐰 𝐬𝐭𝐮𝐝𝐲 🚨

The following is a comparative analysis of two models that explain serotonergic alterations.

𝐂𝐨𝐦𝐩𝐚𝐫𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐯𝐞 𝐀𝐧𝐚𝐥𝐲𝐬𝐢𝐬: Intestinal Serotonin Models in the Context of Viral Infections 📊

Serotonin (5-HT), known for its functions in the central nervous system, also plays a critical role in gut function. Different models attempt to explain the implications of serotonin in the context of viral infections. I analyze here two models: the model presented by Wong AC, et al and our model.

𝐖𝐨𝐧𝐠 𝐀𝐂, 𝐞𝐭 𝐚𝐥. 𝐦𝐨𝐝𝐞𝐥 (https://www.cell.com/cell/fulltext/S0092-8674(23)01034-6?_returnURL=https%3A%2F%2Flinkinghub.elsevier.com%2Fretrieve%2Fpii%2FS0092867423010346%3Fshowall%3Dtrue ):

1️⃣ 𝐏𝐫𝐨𝐩𝐨𝐬𝐢𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧: It suggests that viral infection inhibits the uptake of tryptophan, the precursor of serotonin. This would lead to a decrease in serotonin production at the intestinal level.

2️⃣ 𝐈𝐦𝐩𝐥𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧𝐬:

– With less serotonin, 5-HT3 receptors in the vagus nerve would not be activated, being responsible for the decrease in serotonin at the central nervous system level.

– This model does not adequately address how an increase in intestinal motility would be generated if there is a decrease in serotonin, given that elevated serotonin stimulates motility generating diarrhea and gastrointestinal symptoms that occur in many patients with ME/CFS and Long COVID.

– It is also not explained how the vagus nerve could be overactivated, causing symptoms of dysautonomia.

– This model suggests platelet hyperactivation primarily due to viral inflammation and interferon production. While it recognizes a procoagulant state, it does not detail the specific role of serotonin or intracellular mechanisms in platelets in relation to hypercoagulability

𝐎𝐮𝐫 𝐦𝐨𝐝𝐞𝐥 (https://translational-medicine.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12967-023-04515-7 ) :

1️⃣ 𝐏𝐫𝐨𝐩𝐨𝐬𝐢𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧: Activation of TLR3 by EBER (or TLR2 by EBV dUTPases) or other viral RNA would inhibit and reduce SERT (serotonin transporter) expression, leading to serotonin accumulation at the extracellular level in inflamed tissues such as the intestinal mucosa.

2️⃣ 𝐈𝐦𝐩𝐥𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧𝐬:

– Elevated intestinal serotonin would activate 5-HT3 receptors, increasing intestinal motility and causing symptoms such as diarrhea.

– Increased serotonin could also overactivate the vagus nerve, explaining symptoms of dysautonomia.

– The decrease of serotonin in the central nervous system would be produced by the passage of viral RNAs that activate TLR3 receptors of microglia, causing the release of proinflammatory cytokines IL-1β and TNF-α, which increase the expression and activity of the serotonin transporter SERT in astrocytes, causing an increase in serotonin (5-HT) reuptake and a decrease in its extracellular levels.

– Both the increase in proinflammatory cytokines and the increase in oxidative and nitrosative stress (ROS/RNS) by activation of microglia through TLR3 could lead to increased IDO activity in microglia, resulting in reduced tryptophan (TRP) levels, increased quinurenine catabolites and decreased 5-HT synthesis.

– In our model, TLR3 activation, in addition to its effect on serotonin transporters (SERT) in the intestine, would also influence platelets. Inhibition of SERT in platelets by the action of TLR3 would reduce the ability of platelets to reuptake serotonin at the intestinal level. This leads to additional accumulation of serotonin in the intestinal tissue, further aggravating symptoms. Extracellular serotonin also activates 5-HT receptors on platelets. This activation, together with viral RNAs acting on platelet TLR3, leads to platelet hyperactivation. This state of platelet hyperactivation would contribute to hypercoagulability.

𝐂𝐨𝐢𝐧𝐜𝐢𝐝𝐞𝐧𝐜𝐞𝐬 𝐛𝐞𝐭𝐰𝐞𝐞𝐧 𝐛𝐨𝐭𝐡 𝐦𝐨𝐝𝐞𝐥𝐬:

1️⃣ 𝐒𝐞𝐫𝐨𝐭𝐨𝐧𝐢𝐧 𝐜𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐫𝐚𝐥𝐢𝐳𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧: Both models agree that, at the central nervous system level, there is a decrease in serotonin. This central reduction could contribute to neurological and psychological symptoms, such as fatigue, anhedonia and other symptoms.

2️⃣ 𝐐𝐮𝐢𝐧𝐮𝐫𝐞𝐧𝐢𝐧𝐞 𝐥𝐞𝐯𝐞𝐥𝐬: Both models recognize an increase in the quinurenine pathway during viral infections. However, they differ in their implications. In our model it is suggested that increased proinflammatory cytokines and oxidative/nitrosative stress leads to increased IDO activity, which reduces tryptophan levels and increases quinurenine catabolites in the central nervous system. This results in a decrease in serotonin synthesis in the CNS.The model of Wong AC, et al. while acknowledging the increase in quinurenine levels, suggests that this increase is not the main reason behind serotonin depletion during viral inflammation, but rather decreased tryptophan uptake. But it is not specifically commented that it would occur at the CNS level.

3️⃣ 𝐈𝐧𝐟𝐥𝐮𝐞𝐧𝐜𝐞 𝐨𝐟 𝐓𝐋𝐑𝟑: In both models, the role of TLR3 in the context of viral infection is recognized, although its influence on serotonin varies between models.

4️⃣ 𝐒𝐲𝐬𝐭𝐞𝐦𝐢𝐜 𝐈𝐦𝐩𝐥𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧𝐬: In both the model in the article and the one proposed by the user, alterations in serotonin levels, either by depletion or accumulation, have implications beyond the gastrointestinal tract, affecting systems such as the vagus nerve and, potentially, the autonomic system in general.

5️⃣ 𝐏𝐥𝐚𝐭𝐞𝐥𝐞𝐭 𝐚𝐜𝐭𝐢𝐯𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧: While the model of Wong AC, et al. focuses on general inflammation and interferon production as drivers of hypercoagulability, our model provides a specific mechanism involving both viral RNAs and serotonin and their interaction with platelets. In this respect, both models may be complementary in describing different disease processes.

6️⃣ 𝐈𝐧𝐭𝐞𝐫𝐚𝐜𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐰𝐢𝐭𝐡 𝐒𝐒𝐑𝐈 𝐃𝐫𝐮𝐠𝐬: Both models recognize that administration of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) in the context of these disorders may have unpredictable effects and potentially exacerbate or moderate symptoms, depending on the individual patient’s situation and which model is considered more accurate.

𝐂𝐨𝐧𝐬𝐢𝐝𝐞𝐫𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧𝐬 𝐟𝐨𝐫 𝐏𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐬 𝐨𝐧 𝐒𝐒𝐑𝐈 𝐓𝐫𝐞𝐚𝐭𝐦𝐞𝐧𝐭:

Because SSRIs inhibit serotonin reuptake, they may have complex effects in this setting:

1️⃣ According to the model of Wong AC, et al SSRIs could compensate for the decrease in serotonin by increasing its availability.

2️⃣ In our model, SSRIs could improve the availability of 5-HT in the central nervous system. However, it could exacerbate gut symptoms and inflammation due to an increase in 5-HT availability at the gut level, possibly exacerbating symptoms.

𝐂𝐨𝐧𝐜𝐥𝐮𝐬𝐢𝐨𝐧:

1️⃣ Serotonin homeostasis in the context of viral infections is an area that requires further investigation.

2️⃣ Given that many patients with ME/CFS have had worsening symptoms with SSRIs and the possible consequence of serotonin accumulation at the gut level in one of the two models, it would be prudent not to recommend these treatments in both diseases until both processes are verified.

3️⃣ It is also possible that both models describe different stages of the same disease, for example, in acute or chronic phases or in flare processes.

Great counterpoint thanks Pablo. This illness often appears to be made up of seemingly opposite subsets and I am almost certainly in the high gut serotonin group that you describe.

Escitalopram made me more sick than I have ever been. Never again.

About twenty five years ago, I was treated by several NIH Neurologists for POTS and chronic migraine issues. These gentlemen had a protocol where they could very rapidly determine a patient’s blood serotonin level while sitting, and then upon standing. Basically, they concluded that my blood serotonin was, indeed, low while sitting. As expected, my sympathetic nervous system would increase my blood serotonin when I stood. I do not remember the exact data, but these NIH Neurologists informed me that my blood serotonin QUADRUPLED upon standing. A normal control would only DOUBLE their blood serotonin level during the process of standing. My standing serotonin was still BELOW normal. But, I needed a four fold increase in serotonin from sympathetic nerves to remain upright. They speculated that my receptors for serotonin post-synaptically were probably also up-regulated to help compensate. Shooting from the hip, they guessed that my condition was “autoimmune in nature”. They told me that I would most likely need to take a mineral corticoid like Florinef to expand my blood volume going forward. As expected, a study protocol was never approved by the NIH.

I have tried Serotin medicines all I wanted to do was sleep, I was on them for over one year.

Has anyone tested to see if they have the Latent form of TB maybe this is activated you are born with this, it can also be seen in Nutcracker Syndrome.

I have an enlarged left kidney on ultrasound. I need a better ultrasound a Doppler done & Veno scans. It would explain my left flank stomach & left kidney pain plus lying on my stomach the pain is 100% higher the compression can be also across the spinal column.

I have had this my entire life. You are Born with Nutcracker Syndrome & Latent form of TB passed on in the womb. There are Gold standard tests for all these conditions.

Read her published paper from a UK GP/patient/author Tamara Keith called ‘I can assure you, there is nothing wrong with your kidney’ They even told her she had FND.

She was negative to the TB infection type she had & was treated for Latent TB & had autotransplantation surgery for Nutcracker Syndrome.

She developed Stenosis in the vein 3 months later she had more surgeries. A stent did not help. She is well today & is a partner GP in Cambridgeshire, UK

Thanks for this Cort. Just sharing this WHYY radio interview with Dr. Abramoff from U Penn Medicine this week, and one of the co-authors from this paper/study [interview starts around 27 min mark]

https://whyy.org/episodes/the-latest-on-long-covid-a-pennridge-dads-book-ban-challenge/?fbclid=IwAR3sl-D9zLlWSpsShJVOx_MCYmnM9X6XProh9bFagS_y_mjHP7qQkv-_dzI

Dr. Abramoff: “Frankly, this wasn’t new to COVID infections. Going back years and years, people who had viral infections and not get over them. That had persistent symptoms. Often conditions, called post-viral conditions, like Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome, or POTS, were triggered by other infections. Other viruses, like other coronavirus infections, the SARS pandemic led to persistent symptoms. And so, we decided as a clinic, we were going to build-in that research question.”

“Through this interferon-related mechanism, we found that is what drove the decrease in serotonin levels…”