The study was small and the results preliminary but it did suggest a different tilt to the immune systems of people with post-infectious onset and non post-infectious onset.

The findings are tentative and need to be validated, but if they hold up they could signal a fundamental split between people who’s chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) was triggered by an infection and those who came down with ME/CFS some other way. If your ME/CFS was triggered by an infection, your immune system may have been tilted in an autoimmune direction. If your ME/CFS was triggered in another way, it may have been tilted towards inflammation.

Time will tell.

Autoimmunity and ME/CFS

Chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) has long been thought to be a possible autoimmune disease. The infectious onset, the gender imbalance (almost 80% of people with autoimmune diseases are female), the age of onset, even the wide variety of symptoms, all suggest autoimmunity might be present.

One might ask why infectious mononucleosis, which was recently linked to no less than seven autoimmune diseases, would not – given that it’s a common trigger for ME/CFS – also have produced an autoimmune disease in ME/CFS?

Establishing that a disease is autoimmune in nature is not easy, however – and while we’re not nearly there yet – the evidence and interest appears to be growing. Dr. Scheibenbogen was the senior author of a Euromene paper, “Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome – Evidence for an autoimmune disease“, which argued that a startling array of immune findings in ME/CFS pointed toward some sort of autoimmunity.

The review paper – which was published prior to the publication of the failed Rituximab trial in ME/CFS – asserted “there is compelling evidence that autoimmune mechanisms play a role in ME/CFS”, while warning that subgroups of patients likely have different “pathomechanisms”. Recently, a hypothesis paper suggested that people with ME/CFS are caught in a kind of weird limbo state between autoimmunity and pathogen persistence.

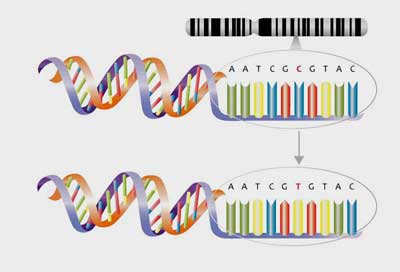

Given the heterogeneous immune findings found in ME/CFS, the authors of the review paper concluded that it was critical to “identify clinically useful diagnostic markers”; in this case very small genetic changes – a shift in just one nucleotide – called single nucleotide polymorphisms as well as immune factors.

The Polymorphism Story

Single nucleotide polymorphism – at times it can take just one small alteration of a gene to change how it functions.

Polymorphisms have been looked at before. A fascinating 2017 review paper which examined no less than 50 studies on the genetic polymorphisms found in ME/CFS, cancer-related fatigue and other fatiguing diseases. It suggested that slightly altered forms of TNFα, IL1b, IL4 and IL6 genes put people at risk for high levels of fatigue.

The connections found between ME/CFS and polymorphisms in HLA, IFN-γ, 5-HT (serotonin) and NR3C1 (glucocorticoid) genes, in particular, were cited in that paper. Several of these altered genes could be tied to autoimmunity or other immune dysfunction. The link between the HLA genes tasked with spotting an invader and autoimmunity is well known. Given the role the HPA axis plays in regulating the immune system, the glucocorticoid polymorphism documented in ME/CFS could play a role as well.

The COMT gene that appears to play a big role in fibromyalgia, and perhaps ME/CFS, breaks down catecholamines like norepinephrine. Both it and the beta 2 adrenergic receptors that are under investigation in ME/CFS modulate the immune response. All in all, it appears that ME/CFS patients’ genetic makeup provides plenty of opportunity for their immune systems to go awry.

The Study

Autoimmunity-Related Risk Variants in PTPN22 and CTLA4 Are Associated With ME/CFS With Infectious Onset. Sophie Steiner1, Sonya C. Becker1†, Jelka Hartwig1, Franziska Sotzny1, Sebastian Lorenz1, Sandra Bauer1, Madlen Löbel2, Anna B. Stittrich3,4, Patricia Grabowski1 and Carmen Scheibenbogen1,3* Front. Immunol., 09 April 2020 https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2020.00578

This present study – another Carmen Scheibenbogen and company production from Germany – assessed whether small changes in immune genes (called polymorphisms) that have been associated with autoimmunity were present in ME/CFS. These polymorphisms usually affect the activation of T or B cells or the production of immune factors called cytokines.

This large study included 305 people with ME/CFS (205 female/100 male) and 201 (103 female/98 male) healthy controls.

The goal was to determine if the immune systems of ME/CFS patients were genetically skewed towards autoimmunity. This is not the be-all and end-all of genetic studies – it examined the frequency of just five polymorphisms in immune genes that have been associated with autoimmunity. They included:

- tyrosine phosphatase non-receptor type 22 (PTPN22) SNP rs2476601,

- cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA4) SNP rs3087243,

- interferon regulatory factor 5 (IRF5) SNP rs3807306,

- gene tumor necrosis factor (TNF) SNP rs1800629,

- gene rs1799724 (TNF) SNP Rs1799724

Two of these gene polymorphisms code for production of a key gene in the pathogen response – higher tumor necrosis factor – (TNF-a); one coded for higher IFN-y production, and two affected T and/or B cell activity or signaling.

Results

Given the limited search, any positive result probably would have been greeted with celebration. The study did better than that, though, as two of the five polymorphisms assessed were upregulated in ME/CFS patients compared to healthy controls.

Infectious Subset Stands Out

There was a catch, though. The polymorphisms were only found with more frequency in the 2/3rds of patients with post-infectious onset.

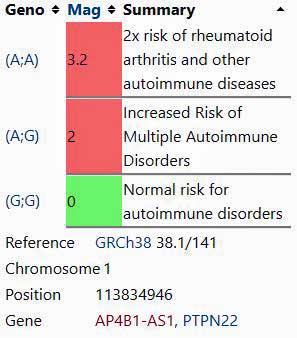

The PTPN22 rs2476601 polymorphism. The gene this SNP is found in – PTPN22 – has been called the archetypal non-HLA autoimmunity gene.

(From SNPedia)

Both of the polymorphisms (PTPN22 rs2476601, CTLA4 rs3087243) have been associated with several autoimmune diseases such as type I diabetes, lupus and rheumatoid arthritis.

The PTPN22 rs2476601 polymorphism is a major autoimmune factor. It is believed to make it more difficult to delete autoreactive T cells, to reduce the activity of the Treg cells in charge of ensuring autoimmunity does not occur, and to impair B-cell clonal regulation.

The Gist

- This study assessed the frequency of five single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that are associated with autoimmunity.

- Single nucleotide polymorphisms are small changes to the genetic code affecting just one nucleotide which, nevertheless, can sometimes dramatically affect the functioning of a gene.

- Two of the five SNPs were increased in ME/CFS patients with an infectious onset. Two other immune factors that have also been associated with autoimmunity were also found.

- In contrast, no autoimmune markers were found in the non-infectious onset group, the frequency of several of the SNPs was decreased and a marker of inflammation (CRP) was increased.

- The authors speculated that the illness in non post-infectious onset ME/CFS may be more akin to that found in post-cancer fatigue.

- Post-cancer fatigue appears to be more associated with HPA axis and sympathetic nervous system dysfunction.

- The study added a bit more evidence to the idea that at least a subset of ME/CFS patients have some sort of autoimmune process going on.

- Twenty percent of the study participants reported that their illness was triggered by an EBV infection. Infectious mononucleosis has been linked to an increased risk of autoimmune diseases.

- Larger studies are needed to determine if the immune systems of post-infectious and non post-infectious ME/CFS patients are indeed tilted in different directions.

The form of CTLA4 found enhanced in the infectious onset group, on the other hand, makes it more difficult to turn off the activated T cells that can drive some autoimmune diseases.

The EBV Autoimmune ME/CFS Group?

Almost 20% of those with a post-infectious onset of ME/CFS reported that their illness was triggered in adolescence by an Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection (infectious mononucleosis, glandular fever). EBV, as was noted above, is a known for autoimmunity. A 2018 paper provided a reason why EBV may be so adept at turning an infection into an autoimmune disease.

Virtually everyone carries EBV in its latent state in their cells. It turns out that even in its latent state, when EBV isn’t replicating, a transcription factor in EBV is still busy turning on and off genes that just happen to increase the risk of developing a host of autoimmune diseases (lupus, multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease , celiac disease, type 1 diabetes.) Fully 50% of the gene regions associated with an increased risk for lupus, for example, appear to have been turned on by EBV.

EBV or any other virus isn’t the end of the story with autoimmunity. Most people who come down with infectious mononucleosis or another infection don’t come down with an autoimmune disease but these stressors, perhaps like other significant stressors in childhood, adolescence or adulthood, can tilt the immune system in a direction which makes it susceptible to producing autoimmunity for some people.

A Non-Infectious Onset Inflammatory Subset?

Interesting, two findings suggested that the immune systems of the non-infectious ME/CFS cohort may be tilted in the opposite direction of the post-infectious cohort. Instead of having higher frequencies of the of IRF5 and TNF risk variants, they had significantly lower frequencies compared to the infectious group.

Finding some genetic alterations in immune genes, the researchers took the next step to see if the unusual gene forms resulted in immune alterations as well.

They did. Several autoimmune-like factors jumped out. Reduced C4 levels in the infectious onset group were reminiscent of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), while reduced CD19+ B cells (B cell lymphocytopenia) are found in both SLE and rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

(“Lymphocytopenia” refers to a count of less than 1,000 lymphocytes per microliter of blood in adults). CD19+ cells are the major immunoglobulin-secreting B-cell found in the blood, bone marrow, spleen and tonsils. Reduced CD19+ cells have been associated with an increased susceptibility to infection in animal studies.

Compare those findings to the increased c-reactive protein (CRP) levels in the non-infectious group of patients, suggesting a more pro-inflammatory profile. The authors suggested the disease in the non-infectious group may be more akin to that found in cancer-related fatigue.

No federal agencies funded this study – it was solely the result of your donation dollars. It was supported by a 2016 Ramsay Grant Program award, the Solve ME/CFS Initiative, as well as by several German foundations.

Cancer-Related Fatigue and the Non-infectious ME/CFS Group

HPA axis problems are present in ME/CFS and recent cancer-related fatigue studies have found a link between HPA axis problems and inflammation in post-cancer survivors with fatigue. A 2020 study found that reduced sensitivity of the immune system to glucocorticoids (cortisol) resulted in increased levels of pro-inflammatory markers and cytokines (C-reactive protein, interleukin 6, and tumor necrosis factor α.) in the fatigued patients. Apparently, the HPA axis was having trouble tamping down inflammation in the fatigued cancer patients.

A head and neck cancer study uncovered a possibly revealing distinction between pathogen (papillomavirus) triggered and non-pathogen triggered cancer. The gene expression results suggested that the two types of cancers triggered different immune responses.

The non-pathogen triggered cancer triggered something called a “Conserved Transcriptional Response to Adversity (CTRA)” immune response. In this response, those beta adrenergic signaling pathways that we’ve been looking at lately in ME/CFS jacked up inflammation via the sympathetic nervous system. The CTRA response was diminished, on the other hand, in the infectious cancer cohort – and so was the fatigue.

While it’s a bit of a stretch to compare infectious onset cancer and infectious onset ME/CFS, it’s intriguing that in both cases the infectious onset was associated with less inflammation.

It brings up the question whether the fatigue in post-infectious onset and non-post-infectious onset ME/CFS patients could be coming from different places. Could the HPA axis/sympathetic nervous system-triggered inflammation be playing more of a role in ME/CFS patients with non-infectious onset?

A 2019 study suggested, though, that an infectious onset may not be so clear a trigger as one might think. Almost 40% of the participants reported that it took 7 months or more from whatever happened for ME/CFS to manifest itself. Twenty percent reported that it took more than two years. Eighty-eight percent, though, felt they could identify a specific triggering event.

While infectious onset seems like it would trigger a quicker decline into ME/CFS, people with infectious onset were no more likely to quickly come down with ME/CFS than people with other triggers. Only 14% of those citing an infectious onset said their ME/CFS developed within a month of the infection.

Conclusion

The study found that two gene variants – including one in “the archetypal non-HLA autoimmunity gene”. found in autoimmune diseases were also increased in people with post-infectious ME/CFS. Plus, several immune factors associated with autoimmunity were increased as well. While autoimmunity hasn’t been proven in ME/CFS, the study provided more evidence that autoimmune processes may be at play in a large subset of ME/CFS patients.

The story appeared quite different in people with ME/CFS who didn’t have an infectious onset. Two of the polymorphisms associated with autoimmunity were significantly decreased in the non-infectious onset ME/CFS patients. Plus high levels of an inflammatory marker were found as well. That suggested that the pathology in the non-infectious group might be more akin to that which occurs in post-cancer fatigue.

Studies suggest that the post-cancer fatigue and non-infectious onset ME/CFS patients may have a balky HPA axis that has difficulty reigning in inflammation. Interestingly, given the focus on the sympathetic nervous system in ME/CFS, non-pathogen triggered cancer was associated with more sympathetic nervous system-induced inflammation than pathogen-triggered cancer.

While larger studies need to be done, these preliminary findings suggest that the kind of triggering event (or the absence of a triggering event) could have tilted the immune system in different directions in different sets of patients.

With the Nath intramural study focusing on documented post-infectious ME/CFS cases underway, and his new study on post COVID-19 patients beginning, plus all the media attention being given to problems recovering from COVID-19, some real insights may be in store for the post-infectious group.

Excellent progress! This is exactly what we want and builds upon earlier findings by researchers in the past of activated immune cells in people with CFS. I want to go to Germany and get tested LOL. I wish.

Thanks Again Cort. Another interesting post. I’m a post EBV and share very similar stories and symptoms with Other followers.

Anyone else have a constant severe thirst or am I unique ?♂️

I must say I’m a little jealous (no known infectious onset). EBV could hold the key to so much. It’s possible that other infections simply trip off EBV or other herpesviruses. A tendency towards EBV reactivation in the face of another infections could come into play.

Have you checked out diabetes insipidus?

Is diabetes insipidus a separate diagnosis or is chronic thirst a part of ME diagnosis, if you see what I mean?

I am not very scientifically-minded so please can you tell me if a non-infectious on-set ME person is likely to have the inflammation related symptoms of extreme thirst, dry and inflamed skin, cystitis, thrush, PCOS, stress and adrenal issues, etc?

Many thanks

Cort,I think it would be better to be in the ‘non-post infectious’ group, because if they don’t have any autoimmunity affecting their disease, then in the future if the ‘Metabolic Trap’ hypotheses was correct and they are able to be permanently reverse the trap, those people will remain healthy.

But in the ‘post infectious’ group I have a feeling if the ‘metabolic trap’ was reversed, then it could well be pushed straight back into the trap again by an autoimmune response.

Because I suspect in the ‘post infectious group’ there maybe a specific molecule/metabolite being released from cells during exertion which is mistakenly targeted by the immune system because this ‘specific metabolite’ would appear to have an antigen or epitope on it that has been incorrectly identified as foreign, then attacked by the immune system causing the ‘Cell Defence Response’ to push the patient back into the metabolic trap again, so the patient being treated would feel ill then healthy then I’ll over and over. In other words when it is eventually possible to reverse the ‘metabolic trap’, the new found energy production will start producing many more metabolites including an increase in that ‘specific’ metabolite with a recognisable antigen on it, which would trigger a massive autoimmune attack. So the ‘Metabolic Trap’ cure for the ‘post infectious’ group could well be a depressing repetitive seesaw effect of good health flipped back to bad health. Like extremes of feeling good to really bad PEM. So not a cure for that group

So I’m thinking the ‘non-post infectious’ group will have better hope.

Unless someone finds a cure for autoimmunity. That day we will see probably all autoimmune diseases cured and the ‘post infectious’ ME/CFS group healed too. But then will the ‘post infectious’ ME/CFS group still need pulled out of the ‘metabolic trap’?

nah. my ebv has always been negative for reactivation although it is in my serology. same for q fever. that was negative serology too. Chronic fatigue syndrome has nothing to do with the infectious agent which triggered it. It has gone. Hit and run.

Thank you for posting this! I have post-infectious ME/CFS (I almost died of a coronavirus in 2014 and have been sick ever since. I want to participate in any future studies.

I may be wrong here and misrepresenting his idea, or I may be completely off target with merging the ideas above(which I need to read with more clarity than I have) with his. If so, I apologize if I am; however, a researcher named Dr. Bhupesh Prusty has been gaining traction in his research that shows HHV6 can reactivate in certain people and he suspects other viruses (possibly EBV) can too. The interesting concept is that he believes and has found that it can do so outside of the blood and in other tissues of the body Depending upon what area of the body that it infects. The important point I am making is that this can happen without any positive blood tests To the virus. So you could conceivably be part of a certain infectious group with negative blood tests.

Post EBV as well along with several other herpes viruses and experience severe thirst too, though it can come and go… also dry eye/mouth/skin. Just some of the many unfortunate symptoms that come with ME.

Thanks Leslie – identical that ! Dry mouth and cold sores …. plenty worse though …

I’m post-EBV and extreme thirst is an issue, especially if I am recovering from a crash where I’ll commonly down several liters per day. I don’t technically “thirst” for water until I start drinking, but then I can’t stop. Drinking water also marginally reduces the severity of my symptoms.

Winston, I’ve noticed over the years that I don’t ever feel thirsty, even though I believe that at times, I’ve been dehydrated.

Thanks Cort, super interesting and always appreciate your breaking down the science to be more easily understood. Feel like I could fit into both the post infectious and non post infections categories if that’s even possible.

I would be shocked if there’s not some overlap. We still don’t know what’s core in ME/CFS. I imagine different pathways may lead to the same place.

Thanks Cort, but the big question, even if you fall into the auto-immune group or the other group, is there something to do about it?I live in belgium, maybe in verry small steps laying down in a car I could go to scheibenbogen. But can she do something about it? Do you know that? I have thought about my illnes onset, I am ill over more then 3 decades allways declining. and there where certainly different triggers (infectious, non infectious, not known, etc) for every decline. Even one stupid one of a verry hot summer. I am afraid it is an and, and, and storry with me/CFS when I see where I started in my illness with symptoms and all the way down and feel my boddy now. Why can they not work all together these researchers just like with covid 19? We would be so much further. but at least it is one of the bigger studys. On the 17th the european parlement will vote to get money from horizon 2000 for (they call it here) cfs research. Many scientist have signed for it. I hope if money is going to be used for me/cfs that the world will work together. I had big trouble to read the blog because I am so severe. Would it help to go (laying down) to scheibenbogen or is it just to early and can she also not do anything with the findings? Do you know?

Fatigue is highly prevalent in autoimmune diseases. We may not cure the autoimmune condition but there may be ways to address the symptom of fatigue through treatment. This is a good article: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2019.01827/full#:~:text=Profound%20and%20debilitating%20fatigue%20is,fatigue%20syndrome%2C%20and%20rheumatoid%20arthritis.

I also think there is some additive factors involved at onset of the disease process. My CFS started as a combination of a post-EBV infection along with an extremely high-stress period in my life. Maybe the heightened stress levels could be the common factor, which would explain the female dominance noted, as women (and more sensitive men?) tend to internalize their stress while men tend to let their’s out.

The excessive flooding of the excitatory neurotransmitters (Serotonin/Glutamate, etc) would become neurotoxic at that level (explaining all the inflammatory effects seen); while the viral effects, etc could intensify the response. This would also explain why SSRIs/ SNRIs like Cymbalta along with GABA mimics like Benzodiazepines/ Neurontin/Lyrica seem to help (at least officially for FM)

I have had a severe thirst problem from the start of my M/E 27 years ago. Only just recently I was told I now have diabetes, it may be type2 but am being tested for LADA type 1.5 at the moment caused by autoimmune disease. I had been tested in the past but nothing had ever showed up. So possibly may have been diabetes insipidus as Cort mentioned. I also have very high B/P and POTS (autoimmune also) which started early on with M/E.

It’s interesting my TCM doctor from China has always said from the start (20 years plus) that M/E is an autoimmune disease.

I have recently tested positive to APS, another autoimmune disorder, and am now in the process of being tested for possible Polycythemia.

I just want to say a big thankyou to all of the M/E doctors and researchers out there who are trying their best to help all of us afflicted with this terrible disease, and also to you Cort for all your hard work in keeping us all informed of their endeavors. It is much appreciated!

Regards, Josie (from Australia).

My onset was post viral, though not immediate, was within 3 months after having one of three viruses – CMV, EBV and RRV. I thought it was only the flu I had in June’93 and so wasn’t tested straightaway. Then it was in September’93 that I got M/E. (I then tested positive to all 3 viruses).

I have had a severe thirst problem from the start of my M/E 27 years ago. Only just recently I was told I now have diabetes, it may be type2 but am being tested for LADA type 1.5 at the moment caused by autoimmune disease. I had been tested in the past but nothing had ever showed up. So possibly may have been diabetes insipidus as Cort mentioned. I also have very high B/P and POTS (autoimmune also) which started early on with M/E.

It’s interesting my TCM doctor from China has always said from the start (20 years plus) that M/E is an autoimmune disease.

I have recently tested positive to APS, another autoimmune disorder, and am now in the process of being tested for possible Polycythemia.

I just want to say a big thankyou to all of the M/E doctors and researchers out there who are trying their best to help all of us afflicted with this terrible disease, and also to you Cort for all your hard work in keeping us all informed of their endeavors. It is much appreciated!

Regards, Josie (from Australia).

I’m going to have to read this a bit more carefully and then go look up my SNPs to see if I have the mutations mentioned!

Being an EDS girl, and also having a number of past nasty viral infections, I’m not sure which are the cause of my ME/CFS. I seem to have had fatigue before those infections, and yet with each additional illness, the fatigue got worse. It was very clear that the illness caused the fatigue because it manifested shortly afterward. I wonder if it is possible to have both viral and non viral onset?

EDSers are prone to additional autoimmune disorders. But now researchers think infections like EBV can trigger autoimmune disorders. Most EDSers have high levels of fatigue, they all couldn’t have had these viruses. I just don’t know…

Pretty compelling piece of work. Very strong differentiation between post-infectious and non post- infectious.

There are some interesting advances occurring in autoimmunity so fingers crossed.

I’d be delighted if the German group’s study and the wider current spotlight on post-Covid fatigue helps boost knowledge of infectious onset ME. That said, I’m concerned that those of us with non-infectious onset ME will be left out in the cold while researchers head where the research dollars are.

Yes, you are right. all eyes are now on post infectious me/CFS. That consernce me to and like you wrote, the other onset groups will be left in the cold. It is just not fair but what can we do?

Fiona and konijn, same here. I just wrote a comment about feeling validated that non-infectious onset is discussed in this paper!

I am feeling validated by this article because some people doubt that I have ME/CFS because it doesn’t seem to have been triggered by a severe illness. I developed ME/CFS after a series of stressful, unrelatd events that culminated with my sister’s suicide. I had a “nervous breakdown” and eight years later still have the classic ME/CFS symptoms (post exertional malaise, etc.). I wish researchers would mention non-infectious onset routinely in their papers and articles. Again, happy to see it discussed here!

Mary, I didn’t see your comment before I posted mine below, as it took me so long to think about what I was attempting to say and try and make it sound coherent.

I believe I’m building up a picture of what happened with me and I’ve just started to understand Robert Naviaux’s Dauer idea.

I didn’t know what everyone was referring to – but for me, the penny’s dropped now and his theory and the metabolic trap idea appear very relevant to my situation.

No one but me understands my situation…

People on here are talking about being post EBV. According to Dr Byron Hyde, EBV can not cause an ME epidemic as the incubation period is too long. ME incubation periods are I believe 4-7 days and EBV incubation periods are a lot longer I think. I am angry because when I had the virus which I suspect of causing my ME, I flew to the UK to see my GP and I demanded a virus study during the viral illness. She said “We don’t do that.” So I never did know which virus caused my ME. Apparently it should be an Enterovirus according to Dr Byron Hyde who has studied ME and CFS for more than 30 years and has seen over 1000 patients during that time.

I think the onset is not an acute infection with EBV, but a reactivation of the EBV virus that most of us have from childhood. Thus, the onset can be in a couple of days rather than weeks…similar to getting Shingles from your old Chicken Pox infection.

It wasn’t EBV at Incline Village though. Half had EBV infection and half were negative for EBV. My EBV and CMV titres have always been negative old infections.

Teenagers do get ME/CFS after glandular fever though which is EBV acute infection.

Thanks, Cort.Really interesting. Is there a qualitative difference in the infectious- and non-infectious-onset fatigue types and where does post-exertional malaise fit into that?

I second your question, Sue!

It appears that the study used the International Consensus Criteria as their case definition, so that would mean that all participants experienced an ME-specific version of PEM.

But this begs further questions. How can immune systems tilted in opposite directions produce the same core symptom? And not only that, but a symptom that often distinguishes each subset from its corresponding similar conditions? In other words, PEM in non-infectious ME seems unique or at least more intense than versions of fatigue in many other inflammatory conditions. Likewise with post-infectious ME vs. most known autoimmune diseases, though I realize that autoimmune patients do get “crash”-like flares. Why the outstanding difference?

From my non-medical pov, it seems like there’s still be some missing pathomechanism that unites the two subsets.

For me, I think there are a number of distinct symptoms that I have had over the years, which became tangled up. I have spent a long time trying to track them and work out what belongs to what.

I was relatively healthy as a child, apart from repeated bronchitis + antibiotics. At seventeen, I developed glandular fever/mono.

I rested at the time and seemed to get over it. However, I believe it kept reactivating throughout my 20’s and early 30’s if I became tired/rundown – I would then consistently have a sore throat, swollen glands in my neck and become very tired.

I seemed to improve in my later 30’s and early 40’s, the reactivations seemed to stop and I had loads of energy.

However a different phase was about to start. I think I was already starting to have an issue with fructose and alcohol. I wasn’t a big drinker but even a small amount of red wine was having a greater effect then it previously would.

I then had an extremely psychologically stressful and traumatic experience, which had long term consequences. No one understood what had happened and I believe this triggered a chronic sympathetic nervous system response, which resulted in a cascade of issues over the years.

Like Amy Proal PhD’s snowball concept, I just started gathering health problems – like gut issues, immune system activations, intolerance to fructose, dairy, grains, rice etc. My stress levels were rising, my sleep deteriorated and I was utterly exhausted.

Over the years I went to various specialists but nothing showed up. I had some very frightening symptoms. As I became intolerant to so much food I could hardly eat anything. For a while I found that I could get energy from nuts, so I did well on them, until I lost them too…

I became thin, pale, felt cold and my blood pressure was a bit lower than normal. There were times that I lay on my bed and I felt I barely existed – I was just about ticking over.

It was during this time (2016) that I think some hormonal changes were occurring and then I started to bleed. Like warm, bright red blood. It turned out I had a fibroid but this wasn’t recognised by the young doctor I saw in the hospital.

However, I was given progesterone tablets to stem the bleeding and a few months (!) later, during an investigative procedure, the surgeon found the fibroid and removed it. I had also developed an infection and was given IV antibiotics and then had to take two more doses to clear it. I had also become anemic.

Unfortunately a month after that, I developed the worst flu I’ve ever had. I was very unwell for a solid three weeks and my temperature reached 105/41. It took me about three months to get over the worst of it. This illness and high temperature is what caused, what I believe was brain inflammation, as in Dr Jarred Younger’s version.

I was still fairly thin, for me, and was desperate to find things to eat. I remembered that chocolate had given me some energy before and though I had a problem with fructose, I thought I’d give it a try.

I think it was because I was somehow reacting to it – the chocolate then raised my blood pressure, put colour in my cheeks, warmed me up and I put on weight.

This all then became completely out of control because the chocolate set off my sympathetic nervous system too much. I was then ‘spending’ too much energy, not sleeping and was still intolerant to most food. I couldn’t think properly, I had zero memory, so I was truly desperate to find something to help me.

I’d come across Dr Nancy Klimas and then found Dan Neuffer and just thought to myself – you have to calm down and get better sleep. I wasn’t even convinced this would work but I didn’t actually have any other options.

So, I attempted to calm my sympathetic nervous system and sleep better. Thankfully it worked…

Since then (last year), I’ve continued to work on all aspects of my health. I’ve settled my brain down – it’s not so reactive anymore. Calming my SNS and sleeping better, has enabled me to eat more food.

Addressing my inappropriately triggered early childhood adverse experiences, and being able to put that experience into words and to have those concerns heard, undoubtedly helped too.

So, I think the glandular fever/mono resulted in me having reactivations in my earlier adult years. But for over a decade now, I believe my chronically fired up HPA axis and sympathetic nervous system have been major controllers of many systems in my body, completely wearing it down. Thankfully, I’ve been lucky enough to figure quite a lot out myself but I wouldn’t have managed it without all the researchers and contributors who share information online.

My symptoms began right after getting vaccinations. Does that put me in the post infectious subgroup I wonder?

Great question. Since the vaccine is probably a muted or part of a killed pathogen that’s an interpretation that could be made.

It is such good news that these things are being researched . Twenty five years ago I had a coxsakkie virus and was so ill I could hardly even hold a book up to read in bed . It took 3 months of bed rest before I was able to work again . I was fine for 2 years then wham !! It hit me again . Back to bed for 2 weeks . This has gone on for 25 years on and off and rest always helped in the past but I now have polymyalgia as well and nothing is helping – it was dreadful in the hot summer . Believe me I have tried EVERYTHING and spent a fortune on all sorts of potential “ cures” Nothing has helped . I am currently eating sugar-free, gluten-free and only very little dairy . Please find something that helps with the lack of energy ! Even washing the dishes is exhausting !

Does any of those SNPs show up in mono patients who did not develop autoimmune disease?

The study only says that ITO group has certain markers. The rest is speculation based on the fact that some of those markers also shows up in autoimmune diseases. The group could also could have other markers like antibodies that does not exist in non-ITO group. Conversely, non-ITO group could have stress/injury markers that ITO group doesn’t have. All these doesn’t necessarily mean there are different subsets of CFS. Rather, it could only mean that different groups that took different paths to get to CFS have different scars.

Fascinating! Though no viral testing was done, viral hepatitis was suspected at onset. I had a positive ANA initially although no specific autoimmune disease was identified.

ME/CFS is not a disease but the reaction of the body to biological stress overload.