It’s always hard to lose a loved one, but the deaths in ME/CFS seem particularly hard. They tend to be quite painful, they often take place in the midst of a non-supportive medical system, and they’re a complete mystery. With no seeming way out it’s no wonder that suicide is not uncommon.

Death, when it comes, can leave a silver lining, if not for the person who died, for those whom she/he left behind – an opportunity to learn what went so wrong for their loved ones.

Autopsies have been used for hundreds to years to help to understand the cause of death. (Rembrandt)

Autopsies can sometimes provide that. Autopsies are surgical procedures designed to determine the cause of death. Most people who die are not given autopsies. They are usually done in cases of sudden death or in cases where the death was a puzzle. They often produce surprise diagnoses that were not suspected at the time of death.

While autopsies are helpful, they are not the be all and end all. It’s thought autopsies pick up only about a fifth of the missed diagnoses a person might have.

Autopsies and Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS)

The autopsies done in ME/CFS are few and far between. Complete medical histories appended to them are, at least in the public realm, usually lacking.

Because autopsies of ME/CFS patients invariably come from the sickest among us, they may not tell the story of less severely ill patients. Doctors report that most people with ME/CFS/FM get worse at first, then improve and usually plateau. A significant subset of patients, however, decline.

This is that group. Of the ME/CFS patients below whose illness duration is known, none had ME/CFS for much more than 10 years.

A look at the autopsy records (such as they are) suggests that, not surprisingly, when people with chronic fatigue syndrome die, they die in a variety of ways. One theme does, however, stand out and could suggest why some severely ill patients get so ill, why they die, quite frankly, in such horrible ways, and why suicide is not uncommon at all.

A Focus on the Brain and Spinal Cord

The history of documented brain abnormalities in ME/CFS, of course, goes way back – at least three decades – to the reports of white matter abnormalities scattered across the brain. Because the abnormalities were found in different places depending on the patient, and because they’re also sometimes found in healthy people, it wasn’t clear what they meant. Such abnormalities were, however, more common in people with ME/CFS. Something was going on.

One of the more striking and immediately understandable (to people with ME/CFS) findings indicate that people with ME/CFS use more brain resources and expend more energy than healthy people when doing cognitive work. Another not so surprising finding – at least to people with ME/CFS – was that exercise took their cognitive faculties for a tumble and altered their brains’ functioning.

Metabolically that made sense. Metabolic studies present a picture of an undercharged, aerobically challenged, free radical-pummeled brain that may be low in oxygen at the microvascular level. Findings of impaired basal ganglia and motor cortex activity suggested that the signal for the muscles to move might just not be getting through. The Japanese and the recent Younger findings of widespread neuroinflammation may be getting at the core problem in ME/CFS.

In short, there’s reason to believe that a peek at ME/CFS patients’ brains after death might very well reveal something. Autopsies of ME/CFS patients’ brains have been rare, but last year an extensive one was done.

Neurodegeneration I

A formerly active woman back in 1974 began repeating herself and having cognitive problems. Over time, she experienced malaise, headache, joint and muscle pain, swollen lymph nodes and brain fog. Resting did not help and she continued to decline until in 1987 she was admitted to a hospice with a chillingly imprecise diagnosis: “general decline”.

By then, she’d been diagnosed with ME/CFS, fibromyalgia, celiac disease and hypothyroidism – nothing her doctors felt could be causing her slide into death. Except for the fact that she was apparently dying of it, she seemed to be a typical ME/CFS patient.

In her last week she became delusional, but in one respect she was hauntingly accurate, telling her family as she drifted in and out of consciousness that, “There is something wrong in my brain. I am dying.”

After being ill for just 12 years, she died at the age of 74 in 1987. Someone at the time had the presence of mind to collect slides of her brain. Thirty years later, thanks to funding from the National Chronic Fatigue and Immune Dysfunction Syndrome Foundation, her brain was examined by researchers at Temple University.

They couldn’t explain how whatever happened to her happened, but they were able to shed some light on what happened. It was not pretty.

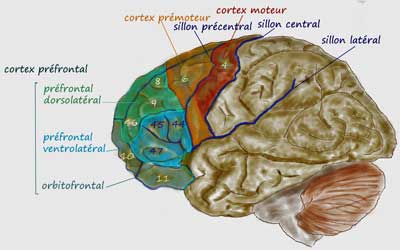

Numerous signs indicated that this woman’s frontal cortex (executive control, organization, planning), basal ganglia (reward, fatigue, movement) and thalamus (motor signals, alertness, sleep) had degenerated. Each of these regions of the brain have been associated with ME/CFS before and it’s striking, at least to me, that areas involved with motor activity (i.e. movement, alertness, consciousness and sleep) were the most affected. Neuronal damage was severe with a marked increase in astrocytes – a common finding in autoimmunity.

Microvascular blood flow was probably impaired as the walls of the small blood vessels in her prefrontal cortex had become thickened and exhibited signs of atherosclerosis. Strange fibrous tangles were found in her basal ganglia, thalamus and frontal cortex. Numerous amyloid plaques similar to those found in Alzheimer’s were found around her blood vessels.

A “tauopathy” – a buildup of tau proteins, also found in neurodegenerative diseases such as frontotemporal dementia (FTD), posttraumatic stress disorders (PTSD), dementia pugilistica, and chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), was present.

Neurodegeneration II

The ME Association found a “vast excess” of glassy looking cells called corpora amylacea in one person’s spinal cord and brain. Derived from astrocytes, these cells are common in neurodegenerative diseases and are often associated with aging. A marked dorsal root ganglionitis was found in another case. Two more cases showed mild excess of lymphocytes with nodules of nageotte in the dorsal root ganglia.

Infection

Alison Hunter

Alison was 19 when she became ill. She experienced severe, fluctuating headaches, dizziness, fever, throat ulcerations, muscle and joint pain, fatigue, seizures, neck rigidity, photophobia, abdominal pains, nausea, diarrhea, bloating and weight loss. A slow recovery from childhood infections had been noted. She died in 1996 after ten years of illness.

An autopsy, however, had revealed little. Hoping that as ME/CFS research proceeded, future investigations would reveal more about what happened to their daughter, her family preserved tissues from her brain, spleen, liver, lymph, heart, lung and other organs. In 2016, tissues from her brain were examined for changes to astrocytes and microglia. Remembering Alison’s trips to farms in Australia, tests for antigens to and DNA from coxiella burnetii – the bacterium that causes Q fever- were made with her tissues.

C.burnetii antigens were found in her brain, and antigens and “substantial” amounts of C. burnetii DNA were found in her heart, lungs, spleen and liver. The authors concluded that the likeliest explanation for Alison Hunter’s decline and eventual death was a severe Q fever attack that infected her organs, causing brain and heart dysfunction; i.e. she had a post-infective fatigue syndrome.

The authors noted that the connection between Q fever and long lasting fatigue was thought to be “psychogenic” until the late 1990’s. Studies by the Q Fever Research Group indicate that Q fever illness can, in fact, proceed atypically with no signs of bacteremia, inflammation, etc. and without eventual elimination of the bacteria. They noted Alison Hunter’s case was particularly severe.

Undiagnosed Seizure Disorder

In 2005, Alan Cocchetto, the Medical Director of the NCF, wrote that a medical examiner concluded that a person with a longtime case of ME/CFS and fibromyalgia died of an undiagnosed seizure disorder (epilepsy) which lead to a fall. The fall appeared to trigger rhabdomyolysis, which led to multisystem organ failure (shock), renal failure and death.

An autopsy indicated insufficient blood supply (ischemia) to the gut – a condition that can produce symptoms like abdominal pain, vomiting and diarrhea – symptoms that have shown up in several ME/CFS autopsy cases. Degenerated astrocytes indicated some nonspecific neurodegeneration had occurred. One defect in the right occipital lobe was found.

A Common Theme? Dorsal Root Ganglionitis

Sophia Mirza

Sophia Mirza had always recovered before. After the two car crashes, the suspected meningitis, and the two malaria infections, she recovered, but it was a flu at the age of 26 that got her. She quickly became homebound and then bedbound.

First came the chemical sensitivities, then the hypersensitivities to light and sounds and touch. After being forcibly removed to a mental health facility, her symptoms worsened. Upon returning to her apartment, she struggled to improve and seemed to get better until small amounts of food and water began causing her pain. Knowing what lay in store for her, she refused to return to the hospital and died in 2005 at the age of 32.

The inquest determined that she died of acute renal failure as a result of dehydration. A later examination of her spinal cord found “unequivocal’ inflammation in her dorsal root ganglia. The doctors reported that:

“The changes of dorsal root ganglionitis seen in 75% of Sophia‘s spinal cord were very similar to that seen during active infection by herpes viruses (such as shingles).”

Merryn Croft

In August 2011, 15-year old Merryn came down with hives after a trip to Mallorca, Spain. Tests revealed she had, at some point, contracted glandular fever (Infectious mononucleosis). Over time, her health declined in a familiar spiral: severe migraines, stomach problems, problems swallowing, slurred speech, exhaustion, and an excruciating hypersensitivity to touch, light and sound.

Unable to eat without severe pain and vomiting, she was fitted with an intravenous feeding line, but suffered from intestinal failure and was given a terminal diagnosis. After being withdrawn from supportive nutrition, she died the next year in 2017 at the age of 21. She had been ill just six years. No reasons were ever found for her intestinal failure.

A post-mortem found low-grade inflammation of nerve roots and inflammation of the dorsal root ganglia.

Three Autopsy Cases

The ME Association reported on a pilot study of four autopsy cases, two of whom committed suicide and one who died of poisoning. The forth died of renal failure caused by lack of food and water. Like Sophia, Merryn and Alison were all were relatively young (32, 43, 31) at the time of their deaths.

“Marked” dorsal root ganglionitis was found in one person and two others showed signs of dorsal root ganglia degeneration (nageotte nodules).

The Association proposed that these issue may have disrupted sensory and autonomic nervous system functioning causing hyperalgesia (pain sensitivity) and allodynia (skin painful to the touch) as well as contributing to problems with orthostatic intolerance (hypotension), light sensitivity, etc.

Dorsal Root Ganglionitis

Dorsal root ganglionitis (DRG) refers to a disease of dorsal ganglia – nodules found just outside the spinal cord which contain the cell bodies of sensory neurons. Because they rely on sensory signals to the brain and play a key role in pain perception, problems with the DRG could conceivably produce many of the sensory and pain problems in ME/CFS and fibromyalgia. One wonders if Anne Ortegren’s problems with clothes touching her skin could have derived from inflammation in her DRG?

The DRG’s role in autonomic nervous system functioning suggests they could contribute to the dysautonomia often found in ME/CFS and FM.

Dorsal root ganglionitis or sensory gangliopathy has been implicated in the sensory and peripheral neuropathies found in HIV/AIDS, cancer pain, diabetes, and most intriguingly, Sjogren’s Syndrome – a disease that is being increasingly associated with POTS, dysautonomia and probably ME/CFS. Sensory ganglionitis can also be associated with small fiber neuropathy – a condition that is also found in fibromyalgia, POTS and ME/CFS.

According to MedLink, sensory ganglionitis can be triggered by a viral or bacterial infection such as Herpes zoster (Gilden et al 2003), HIV, and Borrelia burgdorferi (Lyme disease). The sensory problems arise from inflammation of the ganglia. Interestingly, abnormal blood supply via the capillaries, leading to the entry of inflammatory cells, proteins and other toxins into the neurons, is believed to play a role. This is because the capillaries that supply blood to the DRG’s tend to be “leaky”, allowing the passage of inflammatory cells, proteins and toxins into them.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is not easy. Typical symptoms of dorsal root ganglionitis do not include fatigue, but do contain some symptoms associated with ME/CFS or FM including allodynia, orthostatic intolerance (hypotension), gut issues, erectile dysfunction, paresthesias (areas of numbness or tingling), memory and gait problems. The sensations of temperature, vibration and touch may be affected.

Nerve conduction studies, neuroimaging, and pathological analyses may aid diagnosis. MRI’s can reveal nerve fiber damage. Biopsies are rarely performed but show nageotte nodules, nerve cell damage and immune cell infiltration.

A Sjogren’s Syndrome Segue

Sjogren’s Syndrome is of interest because of its growing association with POTS in particular. A Johns Hopkins 2014 case series used a high resolution magnetic resonance neurography to diagnose abnormal dorsal root ganglia in ten Sjogren’s Syndrome (SS) patients.

The authors pointed out that the burning sensations found in SS often do not follow the typical “stocking and glove” pattern (found from the feet and hands up) that occurs with most people who have small fiber neuropathy. They called small fiber neuropathy “a surrogate marker of DRG neuronal loss” but noted that the unusual distribution of SFN in SS can complicate getting an SFN diagnosis. Plus, some SS patients with burning or “raking” pain may have dorsal root ganglia problems without having small fiber neuropathy.

Five of the ten SS patients in the study had abnormal DRG’s. The fact that none had evidence of small fiber neuropathy, and that two of the patients improved markedly on IVIG therapy, suggested that dorsal root ganglionitis by itself can cause these burning, painful sensations. It also suggested a new way to search for sensory ganglionitis.

In any case, the finding of sensory ganglionitis in Sjogren’s Syndrome suggests that it may not be long – given the proper studies – before it’s also found in POTS, FM and ME/CFS.

Fibromyalgia and ME/CFS

None of the overviews I saw mentioned sound or light sensitivity. Is it possible, though, that some people with ME/CFS/FM have a heretofore unrecognized form of sensory ganglionitis?

Dr. Martinez-Lavin believes so. He believes that infection and/or trauma trigger the aberrant production of sympathetic nerves within the DRG in fibromyalgia. This sympathetic nerve “sprouting” prompts sensory nerves to fire, causing the pain hypersensitivity in fibromyalgia. (He calls fibromyalgia a “sympathetically maintained neuropathic pain syndrome.”)

The ability of herpesviruses to infiltrate the DRG adds another interesting twist. The intersection of herpes virus infections, sensory disturbances, pain production and the autonomic nervous system in the DRG is potentially exciting.

Treatment

Treatments for DRG includes drugs that target calcium and transient receptor potential channels and glutamate receptors. Interestingly, Ivabradine, which can be very effective in POTS, is being used as a DRG inhibitor.

Sometimes the damaged nodules are ablated or removed. Neurostimulators are also used to regulate them. One report of a treatment-resistant case of migraine found that pulsed radio frequency stimulation of her C2 DRG completely removed her migraines.

Much research is underway investigating ways to affect the DRG’s. Different drugs are assessed, mostly in mouse models. (Quercetin was able to reduce glial cell activity in the DRG in a mouse model.)

Fibromyalgia Recovery

In 2015, after a 34-year old with a history of fibromyalgia, post-traumatic stress disorder and occipital neuralgia (chronic pain in the lower neck, back of the head and behind the eyes) unsuccessfully underwent occipital nerve radiofrequency ablation, two of his dorsal root ganglia were removed. His pain completely stopped, and he regained normal functioning.

An examination of the removed ganglia revealed chronic inflammation and evidence of an active, productive, herpes simplex-1 (HSV-1) infection.

Conclusions

It comes as no surprise that death due to chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) arrives in a variety of ways – unexplained neurodegeneration, undiagnosed seizure disorder, a very severe coxiella burnetii infection, and for several, dorsal root ganglionitis.

The findings of dorsal root ganglionitis in five of the nine ME/CFS patients undergoing autopsy is suggestive. With four of them either choosing not to get more medical treatment or taking their lives, this group, if it is a distinct group, appears to be at high risk. Hypersensitivity to stimuli and eating problems appear to be particularly difficult symptoms. They are not typically found in sensory ganglionitis but if sensory ganglionitis can cause allodynia, one would think it might be able to cause gut issues.

Hypersensitivity to light, sounds and smells may be another issue since the sensory signals may not go through the dorsal ganglia. Dorsal ganglia problems could contribute to or trigger what appears to be a truly horrendous case of central sensitization in many of the severely ill.

(Alison Hunter also had severe gut issues and sensitivity to light. No mention of dorsal root ganglionitis was made, but it was unclear if it had been searched for.)

One wonders if more people with ME/CFS should be assessed for dorsal root ganglionitis, and if it’s present, attempts made to treat it. IVIG is one option.

We clearly need much more data. Complete medical histories and extensive autopsies, particularly of the brain and spinal cord, are needed. Dr. Montoya is now accepting brain and tissue samples, and a brain and blood bank in the U.K. has been proposed. I’m not aware if it’s functioning yet.

- The Montoya Blood and Brain Bank at Stanford University – contact Zoe Kim Kenealy: kenealyz@stanford.edu or Tullia C. Lieb – tlieb@stanford.edu (650) 725-4992

- The ME Association Post-Mortem Tissue Bank – is apparently not up and running yet but the Association is working with a neuropathologist to assess tissues on an individual basis. They provide a Statement of Intent that can be filled out which will allow the procedure to be done.

We also need more information on those most at risk. It seems that hypersensitivity to stimuli and eating problems are common in the severely ill, but studies are needed to fully characterize this group. The Open Medicine Foundation-sponsored Severe ME/CFS Big Data study being done under Ron Davis’s direction, and the last phase of the CDC’s multi-site study, should give us a much better picture of this terribly afflicted group.

Health Rising’s Quickie Summer Donation Drive is On!

Health Rising’s Quickie Summer Donation Drive is On!

Cort, lift the mood before Christmas if u can with some good news if there is any!!

Haha, great comment. Although a very interesting article

🙂

Not exactly an uplifting article I know. I’m sure there will be some good news before XMAS. Progress is ALWAYS occurring.

Or a question. Where do the supporters of Health Rising stand on the NAD+ intravenous therapy for cfs/me?

Many thanks to anyone who replies

Nicole Martin

Re dealing with Crash cycle I have found over many yrs that Low dose Doxepin 2-4 mg can make a difference also helps sleep and digestion..First sold as an antidepressant (old Type) and has side effects such as more dry eye etc..Best to use sparingly but sometimes one shot is enough,Doxepin (partic in low doses)in an antihistamine so I am hoping that now the research is heading in the right direction, re neuroinflammation they will come up with something more targeted.

Here’s some Christmas cheer… I’ve got some good news, I found when I take anti inflammatories before and after exertion plus an antihistamine, and curcumin (taken together and reapeated every 4 hours for a day or two). Also a tea spoon of baking soda in a glass of water morning and night. The above regime drastically reduces the chances of getting PEM. I only take this combo within that 48 hours window of exertion.

Note: always take the anti inflammatory with food or Losec

I also found PQQ Energy and B1, B2 and a B vitimin complex. Improve energy (slightly) I take that regularly.

It’s no cure but anything to prevent the fever like suffering of PEM.

Also the 16/8 diet is helping wake up the lazy mitochondria as they start craving carbs. I still start with a protein shake and healthy fats in the morning, then only long chain carbs from whole foods like vegetables, nuts, legumes i.e. nothing processed. Heaps of fibre in those foods. It stopped my IBS too!

That’s good news Brendan particularly since it makes sense :). Nancy Klimas has found that inflammation starts the whole PEM process going I just put your suggestion in the PEM Busters page on Health Rising

https://www.healthrising.org/forums/resources/crash-flare-busters-for-chronic-fatigue-syndrome-and-fibromyalgia.391/

If there are special anti-inflammatories, anti-histamines or brand of curcurmin you suggest please let us know

Yep I have found curcumin really good too. The only thing that has allowed me to do light exercise without repercussions.

What does one do when you are severely sensitive to so many foods and supplements? I’m in Alberta and trying to find a new Dr as mine is actually mistreating me and he’s not listening to me at all! I cannot eat even rice without severe pain and other gross digestive problems. I’m in constant severe pain all over, cognitive decline, daily seizures and other symptoms that confine me to bed or wheelchair. How do I find a new Dr who’ll actually believe me,?

NAET stands for Nabutripads Allergy Elimination Technique was very helpful for me. It is a technique that can be learned by chiropractors, Natural Medicine Drs, Acupuncturists, etc. just do a web search to find a provider in your area.

A little late… but I had the same issue.

After some reading and experiments, I realized it might be histamine toxicity from all the immune system over-function.

There’s an enzyme that breaks down histamines in the gut called diamine oxidase, or DAO enzyme. You can buy it at a Vitamin Shop, though not in Canada. I have to order mine from the U.S.

Most supplements make me sick, but this one worked like a miracle! I thought I might starve to death at one point, so I hope you are doing alright.

Best of all, the DAO enzyme allows me to tolerate probiotics again, which I hadn’t been able to have for years. Now I realize that microorganisms, both beneficial and not, contain histamines, which is why I need the DAO enzyme to take probiotics.

Best of luck!

Brendan Rob – that *is* *really good* news!

It is so very encouraging about finding some ways to pre-empt and fight back against PEM. I find that PEM is so rough, but not exercising (which I almost decided to give up on, taking walks even) really gives me the creeps. There’s hope!!

I had a similiar experience. Twenty years ago I was on 1800mg of Ibruprofen a day for 18 months due to servere back pain from three prolapsed discs in my lower back, plus the following operation to correct the situation. While I was on them my ME symptoms went down by I estimate 2/3rd, though I was not as badly affected by the ME then as now. The only thing I have come up with why is that Ibruprofen inhibits blood clotting. When blood platelets clot they release serotonin which induces further clotting and vasoconstriction. Is vasoconstriction a cause of the fatigue and muscle pain in ME? Also 90% of serotonin in the body is in the gut and is involved in the nausea and diarhea reactions, a feature of ME. Most of the rest is stored in blood platelets, and it is one of the main neurotransmitters possibly accounting for the neurological problems in ME. However that may just be me, I was diagnosed with a genetic blood clotting disorder ten years ago (my blood clots at a rate seven times normal) after pulmonary embolisms, twice. The ME was much worse after these events though it did recover somewhat. It may be that my underlying genetic condition was flooding my body with serotonin because of the heightened rate of clotting and mimicking ME. I used to keep a few of the really strong ibruprofen (600mg) aside for the really bad ME days, but now I am on warfarin so its contra-indicated. Pity as warfarin does nothing for the ME!

Please do not self medicate on high doses of Ibruprofen!

It’s very dangerous!

My thinking on vasoconstriction is that it prevents oxygen, energy and nutrients getting into the muscles and brain, and conversely stops waste and fatigue products getting out, like getting suffocated, starved and poisoned at the same time, not good.

I find that if I do things slowly its not too bad, but if I have to rush the wall hits very quick, then I have to have a long ly down for the crap in my system to work its way out. I find this also after social events. It feels great when the serotonin is up, even a bit of a rush, but it is a b*stard afterwards.

My current GP persuaded me to try prozac for eight weeks for the ME. My brain felt for the time I was on Prozac that I had not slept for three days constantly. Well if my serotonin was highish to start with, and you add to it, and serotonin is a vasoconstrictor its like having a permanent hangover. It did nothing for the ME, and the GP has not tried anything similiar since. However serotonin is at best a part of the jigsaw of ME, as people who have suffered severely from ME for many years can also have genuine depression which features low serotonin levels.

Best to you all

Can anyone direct me to a researcher who would accept a body donation? I had spoken to someone at Stanford a while back, but can’t – of course – remember how I found that contact. I feel like I need to get a post-mortem donation figured out now. Any info out these would be greatly appreciated.

Hi Nancy. Here is the link to the page with the Stanford blood and brain bank – http://med.stanford.edu/chronicfatiguesyndrome/research.html. I’ve believe there’s been more movement recently.

I’m hoping that others are available and someone will provide information on them. I know it’s been talked about for years in the U.K.

It seems like Solve ME/CFS should be coordinating something like this? They are starting their new BioBank next year but it appears to be “on demand” so they won’t be storing samples. Still maybe you could ask them their thoughts on the issue.

Hang in there the best you can Nancy, there’s hope and therapies coming. It would be a tragedy to lose you especially if in 6 months or a year later a breakthrough came. The IVIG therapy followed by mifepristone trial looks really promising!!!

Brendan, can you share who’s doing this study? I know Nancy Klimas is studying Enbrel and Mifepristone, but I haven’t heard of the IVIG/Mifepristone study yet. Thank you.

Brendon, I’m also interested in who is doing the IVIG trial. Thanks so much.

Here are the contacts for Montoya’s post-mortem brain study if you want to sign up:

Zoe Kim Kenealy:

kenealyz@stanford.edu

Tullia C. Lieb

tlieb@stanford.edu

(650) 725-4992

Thanks Julie. Good for Dr. Montoya to get that going. Not an easy thing I’m sure.

Thank you for these addresses. I’ve emailed them for information and to see if they are interested in me. I’m 79, and have been very sick with everything mentioned in the article, and much more, for almost 32 years. If my body can help someone else I will be so happy. I have nothing else to offer. These diseases have destroyed my life and my family. It would be nice to leave something positive behind!

I attempted to volunteer my brain for this study (I am in the severe group described in this article/currently receiving IVIg). A phone meeting was scheduled, but no one called. This did not feel good at all.

Deirdre in Mass.

Laura in the IVIG group posted 2 yrs ago. Can you comment on your results? And the study results? Peace

Fascinating Article! You do such good work!

Thanks!

I want to donate my body to science. Wondering if When I apply I should include my medical history. I do not have a severe case but have had “chronic fatigue” symptoms for over 30 yrs, chronic depression since childhood, and some symptoms of “fibromyalgia” for over 20 yrs…I live in SD and the medical school in Vermillion accepts bodies. They don’t do atopsies,per se, but dissect the bodies over a period of about 2 yrs.

Yes, a medical history would be very important. I would contact Dr. Montoya at Stanford as well as he’s specifically looking at ME/CFS.

When the time comes I would gladly donate my body to science as well.

Me too Cort. I have said that I want my body donated to science and wondered how to make sure that happens. This article has a lot of good information to get things in order. That said, I’m still going to be around for quite some time ? I wanna know how our story continues to unfold and be here when there’s a cure!

Thank you Cory for another informative article.

Could we get suggestions on Anti-inflammatories, anti-histamine and curcurmin. So many out there, would be great to get information from another CFS/ME person.

Very informative Cort. As you say, I do believe dorsal root ganglia pathology plays a key role in fibromyalgia. Let me add additional evidence to your provoking piece. Dorsal root ganglia contain the small nerve fibers nuclei. Dorsal root ganglia inflammation may induce small nerve fiber neuropathy. Small fiber neuropathy is frequently found in fibromyalgia patients. Specific sodium channels (named Nav1.7) are dorsal root ganglia pain gatekeepers. We found severe fibromyalgia associated to particular Nav1.7 dorsal root ganglia sodium channels genetic variation. Nav1.7 sodium channel structure is well defined. New analgesics targeting Nav1.7 sodium channels are being developed. It is hoped that for fibromyalgia patients these new medications will be better analgesics with less side effects.

I was not aware of the post-mortem ME/CFS cases showing dorsal root ganglionitis. I hope these dramatic and enlightening cases are finally published in the medical literature. They may represent different and important pieces of evidence favoring the notion that dorsal root ganglia play a key role in fibromyalgia and ME/CFS.

I find your posts more informative than many articles published in the “scientific” literature.

Congratulations!!

Thanks Dr. Martinez-Lavin I think I first came across the dorsal root ganglia issue in your work. How not surprising it is that the same problems are showing up in ME/CFS and FM.

Thanks for the information on the Nav1.7 sodium channels. We did a blog on them called “The Surge Protectors” – one of my favorite titles 🙂 Of course, I had mostly forgot about them but looking back at the blog they are fascinating indeed. I urge everyone in pain to read that blog. It may give them hope. Interestingly it mentions that cannabidiol can stop those channels from firing. From the blog

https://www.healthrising.org/blog/2015/12/01/the-surge-protectors-the-next-big-thing-in-pain-drugs/

Augusto Odone(LORENZO’S OIL)demonstrated that lay people can indeed solve medical puzzles and sometimes benefit the scientific research community. Similarly, in the case of CFS, we may be able to, as individuals, compile common anecdotal evidence from the victims of CFS to find a single common denominator. More important would be to begin cataloging the SPECIFIC successful treatment(s) modalities of the victims that are improving.

Notwithstanding; the enormous amounts of diagnostic testing and laboratory analysis that my son has undergone—I wonder if something simple and common to all our victims has been overlooked.

It sounds like those few autopsies have been very revealing. It’s just a shame and a disgrace that many more of them have not been done. Everyone with CFS/ME and/or Fibro should sign a will to donate their body to science and autopsies should be routine.

It is surprising that more have not been done. Certainly everyone that dies of ME/cFS should have an autopsy done simply because no one knows what’s going on. As mentioned above, autopsies often reveal missed diagnoses!

That said, I think there are autopsies and there are autopsies. Some seem to be more complete than the others.

I know what you mean about autopsies. I used to work as a night man in a funeral home; I slept next to the morgue and handled the new arrivals. The embalmers were jolly pranksters.

Heartfelt Thank you Cort for posting this as it clears up all the confusion I was having ?Great article and information to know..

Wishing you and all a blessed ? Christmas

Amazing work…it confirms what i was always trying to say to my gp and family and i was disregarded more or less which left me feeling demoralised..Now i feel restored somehow…thank you…after twenty years of flair ups and only one brain scan in the early years and told it was fine. Brandon Rob i can confirm these work as i swear by them i can vouch the significant reduction in my pain.. I never thought about taking them before and after exertion though…I usually take turmeric latte when I’m in pain..sounds like prevention is the way forward…thank you so much for that. I use east end turmeric which I buy a packet of in most supermarkets in the uk so much cheaper than health store

..it is great stuff..i also use wellwoman max..these include vitamins, omega oils,and lots of other good stuff like co q10 and l lysine which really help me. I also swear by dr oetkrs bicarbonate soda..and I make organic lemon ice cubes for vitamin C if I fancy an alternative. I also use biona apple cidre vinegar with the mother in it at the first sign of any bacterial infection and havent needed to visit gp for that in over a year which shows how affective it is given previously i was up there continuously… i use westlab epsom salts to bathe in to sooth muscles Last one that i use is organic 100+ Raw honey which helps with the throat infection and other viral infections..using all these and doing fruit and veg smoothies with Chia and raw coconut oil and plain bio yogurt has kept me from the gp in over a year

A cure would be great ,I hope people are not considering suicide no matter how bad things get I’m having a really tough time at the moment and fighting flu if there’s trails or cures it would be a miracle

I hope everyone in distress – which I suppose is just about everyone – can have some hope. Two trials are underway (Cortene and Dr. Klimas trial.) and every week it seems we see progress in the research field.

I think pain is probably a huge driver of suicide and the NIH is pouring money into the pain field with the goal of 15 new pain drugs in five years…(!). We’re going to learn a lot about pain over the next five years or so.

it is for so long, that you promised to write about dr klimas trial. I am still waiting.

about the article you wrote, I know it is important to know why people die, but I am so ill, so like dying, that it slapped me in the face. That is not giving courage to severelly ill people who have no hope left to make it untill treatment.

I wish the DEA would stop scaring pain management doctors out of prescribing much needed opioid medication.

Try using a Butrans Patch / Buprenorphine, start at 5 mmg and increase until you receive pain relief. 5, 10, 16 & 20 mmg. Each Patch lasts 7 days. Medication bind’s tight to a neurotransmitter.

The UK tissues bank is up and running. I think the ME Association has the info?

Here’s what I found. The ME Association will do autopsies on an individual basis so long as a statement of intent – which they provide – is filled out.

https://www.meassociation.org.uk/research/research-projects/post-mortem-tissue-bank/

Has anyone used chakra cleansing by chance? I have noticed a complete turn around in symptoms since doing this. Although i do still suffer from some episodes of fatigue, i have found a more holistic approach with healing of hands. I am still new to the discovery of my diagnosis, so i have not worked all the kinks out. I am sharing this with hopes of helping others in my journey to recovery.

Thank you Cort for all that you do. I also have been wondering how I can donate my body to science for the purpose of discovering what the hell is causing fibromyalgia and hopefully lead to a cure . I am in Canada. Does anyone know if Stanford has Canadian connections?

Good work, as always, Cort! I’m sure this article was a hard one to research and write. It was hard to read, and sobering, but it brought a lot of loose ends together for me. It makes my heart break for the level of suffering some patients experience. But it also encourages me that we are getting much, much closer to treatments that relieve specific symptoms. I’m only moderately affected, but I can see myself in everything that was discussed, which encourages me to pursue healing more diligently, to support the work my doctor is doing for me and the plan he’s creating. In other words, this article scared me sh____ss! At 40 years of this, I think I’m a “plateau-er”, but I sure don’t want to be careless and decline! Thank you for your courage in writing this article. You got it done, now you can take a deep breath of fresh air! Thanks, again, for all you do!

Music to my ears, Jennie. I am also taking more diligent care of myself.

Thanks!

Thanks for this, Cort. I just learned about the Sjogren’s connection myself.

I noticed that you used the phrase “committed suicide” twice in this piece. I want to ask you to reconsider that language and use “died by suicide” or another variant like “took their own life” instead.

“Committed” is a term that implies criminality and has led to a lot of stigma for folks who are struggling. This seems extra important in a community where we know suicide is a concern. There are a number of resources available about language and suicide. I’m posting to links below.

https://www.cnn.com/2018/06/09/health/suicide-language-words-matter/index.html

https://www.maine.gov/suicide/about/language.htm

Will do. I was not comfortable with that terminology either.

This is really interesting. My 90-year-old mother, who just died this past July 17th, was diagnosed with frontal-temperal degenerative disorder. She had ME/CFS for 38 years. Her brain was studied by the local university hospital’s geriatric neurologists, and they plan to write a paper about her because most people come down with that particular illness much younger. She only started showing signs of dementia two years before her death.

sorry for your loss, could it possibly be that the ME prevénted dementia from showing up much earlier…

Cannabanoids in medical marijuana have been found to suppress glial cell activation. It is a life saver for me, especially with night time, shooting nerve pain. Cannabis literally dampens my pain response down within minutes.

The link below is to this article, which states:

“selective compounds targeting cannabinoid-like receptors constitute promising therapeutics to manage neuroinflammation”

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2919281/

PS: I really enjoyed this article Cort, I found it uplifting. Uplifting that I’m still alive way more than ten years after infection in 1989.

What does one do when severely allergic to cannabis in any form? Plus I’ve so many chemical and food sensitivities that many home treatments don’t work for me?

Eryn,

You have my sympathies, I understand where you are coming from.

My allergy symptoms and food sensitivities have been improving since I’ve been treating my MTHFR mutations. I did 23 & me, then uploaded data to livewello. This provided an extensive genetic mutation profile. Half of my methylation genes are mutated, along with a homozygous (inherited from both parents, so more likely to cause problems) CBS mutation. I take 1/4 Core Med Science active b12 + active (methyl) folate and 1/2 dropper Pure encapsulations adenosyl/hydroxy B12 morning. Pure O.N.E. multivitamin (formulated for MTHFR) with dinner. Seeking Health ProBiota Histamine X at bedtime. It was key that I stopped taking B3. It blocks methyl folate. I learned this from watching Dr. Ben Lynch webinars on MTHFR. Turmeric/curcummin is contraindicated with homozygous CBS mutation. Pycnogenol works great for me for inflammation.

It might be an avenue worth exploring if you have not already. Best wishes for improved health (:

One thing I forgot. A daily cup of Pacific brand organic bone broth. I make mine with carrot, celery, onion in it. It has helped improve my gut health.

Try Butrans 5mmg patch, it lasts 1 week. If not strong enough go up slowly to 10mmg. It’s also called buprenorphine.

Cort, Ihaven’t been able to keep up with your articles lately, but I read most of this one.

My problem is my doctor has no understanding of ME/CFS. I’ve given up looking for a doctor here. I’m on SSDI with Medicare and secondary Medicaid. Is it worth it yet for me to fly or find someone to drive me to see an ME/CFS specialist???

I’m getting treatment for POTS, OI, Idiopathic Adrenal Insufficiency, depression, insomnia, Restless Leg Syndrome & IBS.

OK – does ANYONE here know where I can get answers to my questions?

Pamj – no I don’t know who is actually treating people with these illnesses but I’ve found helpful protocols on-line in the U.K. If it’s ok with Cort I can post some links or google ME/CFS in UK

Of course.

I have fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome and neuropathic pain. I have been badly suffering for years and I am on disability. I need help. Where can I find a chronic fatigue expert on the west coast? Standford? I am willing to fly somewhere even though my fatigue is awful. Who is up to date on this kind of research? Please help me. Also, did we ever get contact information on the study for alive people or is there only the dead body thing going on?

Hello Christie,

Fibromyalgia is a terrible disease. But there is hope!

Have you read the website from Prof. dr, Bauer in Switzerland? Listen to his lecture on video at youtube. google fibromyalgia and bauer.

Hi Cort,

I’m in Massachusettes. Any ideas of any local tissue donations. I can’t imagine California would take mine. I’m too far away, but would definitely donate my organs, brain etc…for an autopsy study when the time comes.

What do you think of this organization? Before the Stanford biobank, it’s the only one I heard of interested instudying the post mortem brains of people with ME/CFS

https://braindonorproject.org/

I’ve decided to treat myself for brain inflammation if this is possible — inspired by studies in three countries that show brain inflammation in ME/CFS/FM patients, and also a couple of studies that treated brain inflammation in mice by spraying a curcumin nasal spray remedy. The nasal spray is apparently not yet tested for safety in humans, yet there is a history of its use in some countries. I’m using a mist diffuser, with standardized curcumin in the water, in hopes of getting past the blood-brain-barrier, will be taking in a trace amount of piperene. Also taking about .5 gram of curcumin by mouth twice daily (with a trace of black pepper). Also taking boswellia twice daily for pain, and CBD with broad spectrum cannabinoids.

Btw, herbal remedies in the mint family have a history of treating herpes type viruses, so I’m going to add some type of mint and manuka honey to the list as well. It may not be a fast, dramatic or complete treatment but the evidence is growing about the herpes involvement. Since there is growing evidence that herpes-type viruses are involved in ME/FM, and mint and manuka seem to cause no side effects for me, I’m going to cover (such as this is) the herpes issue this way for now. Anybody else trying some of these approaches?

yes, I am trying everything natural I can find research on to quell inflammation and the herpes virus. I just ordered some oil of oregano and I use fresh tumeric root in my green smoothies. I haven’t made a nasal “sniffer” as of yet. Interestingly I know I have the herpes virus as I got cold sores quite frequently as a, child and then here or there as an adult. Then in my early 40s I injured my lower back sledding and got herniated disc. severe chronic pain started then. Few years later I went to the hospital for a kidney stone and they put a Stent in and did surgery to remove it. I then acquired a esbl superbug sepsis. Did IV Meropenem and Ertapenem for 2 months. Then got “pots” and a whole host more in symptoms. I wonder did the infection trigger this or possibly the herpes virus which was controlled by my system grew out of control with all the antibiotics and a perfect place of entrance was my herniated disc. who knows? but definitely interesting. However this would not explain why my teen son has pots after a stomach bug. hmmmm.

I believe my symptoms are also caused by some type of herpes virus. I have a pain in my middle back on the side for 6 months now (not explained by abdomen ultrasound) and episodes of extreme fatigue lasting couple of weeks to a month then getting better. Just a week ago I was admitted to hospital with meningitis symptoms (headaches and eye pain and peripheral neuropathy). I was discharged without explanation of what could have caused it. MRI did not show brain inflammation. Blood tests showed mild infection. GP refuse to refer to any specialist. As I also had 3 cold sores in the last 2 months caused by herpes I decided to get a long treatment of Aciclovir (antiviral for herpes). In UK you can get it without prescription in Superdrug pharmacy if you have reaccuting cold sores or genital herpes. I am planning to take it for 3 months and will let you know if it is helping me.

The first case is most probably Alzheimer disease. I showed the scientific article describing details of the autopsy to a foremost Czech-Canadian pathologist and he replied to me that he would diagnose Alzheimer disease.

I have had fabromyalgia for 45 yrs and suffered from terrible pain. The last 3 years I’ve been suffering from me/cfs/fm. It has come to a point where I can’t get out of bed and just sleep. Today is my birthday and What a way to celebrate–in bed!! My friends are planning a big celebration and I’m going to try to go. It gets worse and more days in bed I pray someone can help. I’ve been to a million doctors and they just don’t understand or get it or care!! Please, please, please can someone help me!!!

Hey Cort,

you mentioned sth. about diagnosing DRG , have you ever heard of someone doing this in ME/CFS can we really see DRG in an MRI,or in any other instrument…. I mean can I as a patient figure this out bevor I die xD

Have a good time !!!

I haven’t but I think Michael Van Elzakker may be looking into this.

Thanks so much for this post Cort. The woman who died after a seizure followed by Rhabdomyolysis hit home for me. Intense muscle spasms during my 37 year old son’s tonic-clonic seizures have each caused life-threatening ‘Rhabdo’ a couple of days later. I’m told, each time I take him back to the hospital for a CK check 2 days after they’ve sent him home the day of a seizure (after I insist they drip an extra bag of saline into him before we leave), that this degree of muscle spasm is ‘uncommon’ in Epilepsy, despite my telling them that Rhabdo happens EVERY time.

And yes, it’s in his chart, but they ignore that in the Emergency Department and still ‘assure’ me that it’s unlikely. His CK counts of 45,000 instead of around or below 300 on that 2nd day mean the enzymes squeezed so intensely out of his muscles are too big for his kidneys to filter so he needs 3-5 days of constant IV saline before they’ll let him back out of the hospital.

They do always admit him two days after, once they see his CK count. Though he hasn’t been dx’d with M.E. because I haven’t wanted him put through the serial humiliation I’ve experienced (and still do with every new doctor I see when a new symptom needs to be dealt with) in my 53 years with this illness. I’m certain this is because he has M.E. too.

His brain gets too scrambled for weeks, sometimes months afterwards to even realize he’s had a seizure. I worry that when I’m ‘gone’ he won’t recognize that he needs to find some way get to the hospital for IV fluids. His Neurologist has always rolled her eyes when I’ve mentioned the possibility of M.E. or, in the first years ‘Fibromyalgia’,’MPS’ (Myofascial Pain Syndrome) ‘CFIDS’ then ‘CFS’ – all of which are in my own chart along with a bunch of other commonly co-morbid conditions – but I’m hoping she’ll be better educated before I leave the planet. I also hope there’s an easily accessible non-invasive biomarker (nanoneedle anyone? please!) well before I’m no longer around to care for him and to get him help when he needs it.

His issues started with a bi-lateral, intra-ventricular cerebral hemorrhage when he was 10 – pediatric intensive care unit for 11 days, then a week on the Neuro floor, followed by intense muscle spasms when he got home; the Epilepsy didn’t begin ’til he was 26 and under enormous emotional stress. Mine started with Mono when I was 18.

His M.E. is mild enough for him to work part time several days a week, collapsing when he gets home and throughout the weekend. Several doctors’ eye rollings have made him resist even the gentlest suggestion that this might be why he is so easily overwhelmed, so I don’t push it at all. Wouldn’t do him any good to know at this point.

I’m hoping I hang around long enough for a diagnosis to help instead of harm him. Am 71 now and my own kidneys aren’t doing so well lately.

I’ve had CFS for 2ours, devastating my life. I’ve just found out about Anthony Williams the Medical Medium. He says most of not all chronic illness is due to viruses, like Epstein Bar (Glandular Fever) and Shingles etc. He provided ps ways to kill them and heal. I’ve been follow a portion of his advice for 1 year and have had marked improvement. Funny that one of the autopsies above points to Glandular Fever. My first blood test 20yrs ago said I had had it, it never leaves your body unless you kill it and science doesn’t know how to but Anthony does. Check him out and begin your healing journey.

Had CFS for 20yrs I meant……

I have had CFS for over 25 years now. I am housebound now and it is getting worse.

I also wanted to share with you my research on the CFS.

I entered all research on CFS from 2018 to present into the one of the most sophisticated artificial intelligence software and its conclusion was that CFS is basically and most likely brain damage, and in some cases also spinal cord damage due to viral infection, TBI/concussions, or degradation.

So it seems to be the brains matter that is damaged (gray matter, etc).

A very pragmatic article. After half a century of being fit and active, and now retired Police Officer, I was diagnosed with ME/CFS and Fibromyalgia. Far from being depressing, this article says it as it is. I for one, appreciate straight talking, and evidence. Anything that leads to a greater understanding of this insidious disorder/disease is most welcome. My heart goes out to the families, but more to those who lived their last moments in a form of hell. Always kiss, and smile at those closest.

Thanks Shane!

I feel exactly as Shane does Cort! Thank you!

I’m not sure if I have ME/CFS, as I’ve never been diagnosed, but some of the symptoms I have been experiencing since I was 10 years old. I feel like there’s no harm in studying up on this just in case. Does it also include bouts of insomnia?

Insomnia is very common but the key sleep symptoms is waking up with unrefreshing sleep. Good luck!

I had a sudden relapse of ME and Fibromyalgia 5 years ago after having severe ME for 2 years, moderate for 12 years and mild for the rest of 27 years. I suspect 3 causes:

1) Polypharmacy resulting in severe side effects and dreadful withdrawals

2) A Herpes virus reactivation

3) A mold exposure

I am now severely ill. Have inflammation and neuropathy all over. A diagnosis of Dystonia (which was probably induced by a drug I was on (known to cause Dystonia) but diagnosed as Functional….. I was investigated for connective tissue disorders and personally think I may have Sjogrens. Nothing showed on tests but Sjogrens is difficult to detect with tests. Same doctor thinks I may have EDS. He has also referred me to a cardiologist who specialises in Orthostatic Intolerance/Dysautonomia. My BP and heart raise significantly when I stand up and sometimes drops. I am now allergic/intolerant to all meds, many supplements and foods, chemicals and perfumes. I suspect MCAS but it is very hard to get a diagnosis for any of these conditions on the NHS in the UK. NICE btw is still prevaricating over changing the guidelines recommending GET and and CBT (even though the study it was based on has been discredited). I’m really sick now but still face disbelief from many doctors….. I know I have some kind of brain inflammation now. I feel it every day, particularly after sleeping. I have also been diagnosed with cervical and spinal stenosis. I will be contacting the ME Association re donating tissue samples. I can’t seem to reverse these new symptoms, largely because of apathy and decline in the NHS services. I have had to go private to get anything at all diagnosed I read your articles with great interest..

Good luck Jennifer! Let’s hope the NHS turns itself around. Maybe the presence of the COVID-19 long haulers will do the trick.

MY HEAD, MY HEAD, MY HEAD is what i used to walk around saying as i hit my head when this first came on over 22yrs. ago and now i have PARKINSONS! Degeneration in my brain from so many yrs. ago started.

Dr. A. Martin Lerner was into EBSTEIN BARR virus and 2 Human Herpes viruses and wanted to do intravenous ANTI-VIRALS in me.

My wife suffers from all 3 (FM/CFS/SS) plus has PTSD from early child abuse. She is 67 years old and is now in bed about 22 hours per day and suffers from most all the symptoms in this article. Is there any hope? All the doctors want to do is push pain meds or muscle relaxers which would all potentially complicate her heart arrhythmia.

Tom check out https://www.drmyhill.co.uk/

Dr. Sarah Myhill has 35 years experience and about 6000 patients treated with CFS/ME. There is no one way to “cure” all patients but Myhill has some of the most experience in this area in the world and has lead a lot of people to a better place.

Cort and everyone : I have some information regarding “leaving your body with ME/CFS/FM to science”. I called Open Medicine Foundation at Stanford Univ. Hospital and they told me how to make arrangements to donate my brain specifically to the Harvard group who is studying that inflammatory aspect. They were quite excited about the prospect of getting it and said they can do a multiplicity of tissue experiments with it. It’s a creepy thought at first, but I always wanted to “use my brain” to do medical research and cure a disease, so this would definitely fulfill that dream, although not quite how I pictured doing it 🙂 Please advise if you want me to forward the contact information. I’ll follow up to ask about the rest of me as well. I’m a model case with all the symptoms and am only on one pill per week, so maybe that’ll help. Over the years I’ve experienced just about everything but POTS mentioned in this interesting article. Thank you so much for it !

I am 78 and live alone, so my first concern is getting any or all of me to them fast enough.

It amazes me that even with information like this, people in the ME/CFS community can doubt that this disease can kill. You can’t even get validation on an ME/CFS message board if you’re this sick.