Two New Zealanders combine neuroinflammation with the HPA axis to produce a unique explanation for ME/CFS and FM.

Neuroinflammation, the hypothalamus and a unifying hypothesis

Mackay A, Tate WP. A compromised paraventricular nucleus with a dysfunctional hypothalamus: a novel neuro-inflammatory paradigm for ME/CFS. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2018:32:1-8.

The HPA’s nexus in two important systems – the stress response and the immune system, both of which almost everyone believes are impaired in ME/CFS – make it an obvious choice for study. The Mackay-Tate hypothesis, though, is unique in that it focuses on a dysfunction in one particular part of one part of the HPA axis – the paraventricular nucleus, in the hypothalamus. It also, notably, links problems in the HPA axis with one of the hottest topics in ME/CFS – neuroinflammation.

They believe their hypothesis could account for just about everything that happens in these diseases.

The Limbic Center

The heart of the neuroinflammatory matter in ME/CFS, they believe, is the limbic system – a primordial part of the brain packed between the brainstem and upper parts of the brain. Its name refers to the fact that it’s located at the limbus (the border) of the brain.

In 2011, Mackay joined Professor Warren Tate’s laboratory in the biochemistry department of the University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand. New Zealand is a small country – less than 5 million people – but it’s used to punching above its weight. It’s got the best rugby team in the world, and appears to have actually eliminated the COVID-19 virus. On the ME/CFS side, it’s got Warren Tate, Rosamund Vallings, has been publishing exercise studies, and now here comes Angus Mackay.

Angus Mackay, the lead author of their paper, came down with ME/CFS 15 years ago during a bout with glandular fever (infectious mononucleosis) while teaching. Mackay, an ex-British army officer, rugby coach and outdoor expedition leader – provides yet another example that this disease can fell the most rugged among us. His disease has waxed and waned ever since then.

Warren Tate and Angus Mackay (From Otago Daily Times). Mackay was an ex-British army officer, rugby coach and outdoor expedition leader before becoming ill.

Mackay took his 1st Class Honors degree in Biochemistry from the University of Dundee, Scotland, and his intuitive understanding of ME/CFS, and teamed up with Tate, recipient of New Zealand’s highest award in science – the Rutherford Medal (2011) – to explore ME/CFS.

With the assistance and mentoring of Tate, Mackay molded his “de novo” ideas into a journal publication in 2018. A year later, Mackay published his neuroinflammatory model of ME/CFS in a New Zealand medical journal.

Mackay used his own symptoms to guide his inquiry. While in a PHD program examining a possible viral cause of ME/CFS, Mackay asked himself what could be causing his own voluminous array of symptoms (aching eyes, temples and spine, “brain fog” (concentration, decision-making and memory problems), lack of coordination, anxiety, depression and withdrawal, debilitating fatigue by day, insomnia at night, temperature regulation and gut problems).

The answer, he hypothesized, was inflammation in the limbic system. The limbic system affects a dizzying array of factors. More about basic drives and functions than anything else, the limbic system affects our emotions, motivation, sensory processing, circadian rhythms, memory, attention, and consciousness, as it’s maintaining the autonomic control of the basic functions of the body.

The limbic system contains the fear center of the brain (amygdala) and interacts strongly with the reward center of the brain (the nucleus accumbens) as well. If a usually innocuous chemical, odor or food bothers you, that could be the result of the limbic system matching or rather mismatching a sensory stimuli with a danger response.

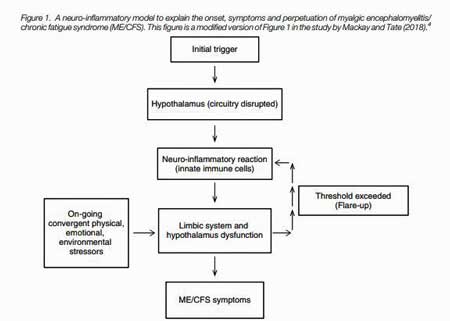

The key organ embedded within the limbic system for ME/CFS may be the hypothalamus (Fig 1). This small – about the size of an almond – but vital organ links the nervous system to the endocrine system, and regulates both the HPA-axis and the autonomic nervous system. It controls body temperature, fatigue, sleep, and circadian rhythms among others.

That means that a lack of refreshing sleep, insomnia, difficulty tolerating temperatures, low cortisol, low blood pressure and heart rate, low blood volume, and gut issues such as bloating could all conceivably be linked to an inflamed hypothalamus.

Stress Response Integrator

One may not need the entire hypothalamus, though, to cause ME/CFS. Mackay’s inquiry lead him to suspect one small part of an already small organ – the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) of the hypothalamus.

Every shock to the system – physiological or emotional – first gets funneled into the PVN, which then integrates the incoming data, decides what to do with it, and then tells the autonomic nervous system and HPA axis how to respond. That makes the PVN a prime target in a disease characterized by a low tolerance to just about any stress (Fig 2).

Talk about walking the knife’s edge. Just about any type of physical or mental exertion or emotional stressor seems to have the potential to produce an effect in ME/CFS. The fact a ludicrously small action – a short walk, mental work, a chemical odor, an emotional stress, or an unusually innocuous supplement or drug – can have a negative effect surely suggests that some part of the stress response system has gone haywire.

The Gist

- Angus Mackay, former rugby player, army officer and expedition leader, used his own diverse array of symptoms to inform his unifying hypothesis of ME/CFS (and fibromyalgia).

- Mackay and Warren Tate – two New Zealand investigators – propose that inflammation in the brain, impacting, in particular, a part of the hypothalamus called the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) could explain ME/CFS (and FM).

- The PVN is the stress integrator of the brain. Signals responding to the different kind of stressors – from physical exertion, to infections, to toxics, to emotional stressors – get funneled into the PVN, which integrates them and determines the appropriate autonomic and other responses.

- Mackay and Tate believe that neuroinflammation is making the PVN twitchy, causing it to over-react to all sorts of stressors. Once the PVN reaches a “stress tolerance level”, it returns the favor, telling the glial cells in the brain to go on the attack – resulting in more neuroinflammation, fatigue, pain, problems with temperature regulation, sleep, cognition, mood swings, etc.

- As the stressor abates, the neuroinflammation calms down, the PVN takes its foot off the stress pedal, and the “crash” or “flare” abates. The more inflammation, though, the longer the PVN takes to settle down and the longer it takes to reach “baseline”.

- Mackay and Tate believe the major neurodegenerative diseases and ME/CFS and FM share a common beginning – neuroinflammation. The kind of disease that results depends on what’s driving the neuroinflammation but the core problem is neuroinflammation. That’s a possibly heartening conclusion for our small fields given the work being done in other diseases to find ways to tamp neuroinflammation down.

- Since the small, but landmark, 2014 Watanabe neuroinflammation paper, only one study has attempted (using different techniques) to validate it, but Mackay reported that Watanabe expects that his larger, more sophisticated study (which validated his original findings) will be published later this year.

- Mackay looks to the day when the ever improving imaging techniques result in a diagnosable brain signature for ME/CFS/FM.

The Tidal Wave

“… when a certain threshold for incoming stress signals is exceeded, might that trigger a flare-up originating in the hypothalamus but spreading out like a tidal wave to specific targets within the brain and central nervous system?” Angus Mackay

Mackay and Tate propose that exceeding a stress “tolerance level” causes the PVN in the hypothalamus of ME/CFS patients to go a bit nuts in an attempt to defend itself. Alarmed (possibly by alarmins from damaged mitochondria) it calls in the big immune guns of the brain – the glial cells (both microglia and astrocyte) – which jump into action producing pro-inflammatory cytokines.

If an invader was there, that would have been one thing – it would have been vanquished – but Mackay doesn’t need a pathogen to explain a whacky PVN. He just needs a system that’s gone seriously off track. He believes that the PVN might just be the vulnerable point in the ME/CFS armory.

Every time the PVN takes a hit, an already upregulated stress response system gets a bit touchier. Symptoms wax and wane as the neuroinflammation increases and then dies down. Higher amounts of neuroinflammation, though, and the touchier PVN that comes with that – will require longer reset periods.

Mackay believes his model is truly unifying because it can account for the diverse range of triggers. There’s no need for “subsets” – there’s just a touchy PVN that’s reacting in slightly different ways. Indeed, Mackay views ME/CFS (along with fibromyalgia) as a “spectrum disorder”. He believes the wide range of symptoms and the characteristic relapses seen in ME/CFS and fibromyalgia could be accounted for by his simple neuroinflammatory model.

The Hunt for Neuroinflammation in ME/CFS and Fibromyalgia

While signs of inflammation can be found in the blood or periphery, Mackay is more interested in inflammation in the brain. While neuroinflammation studies are much rarer than blood studies in ME/CFS, the findings have generally been more consistent.

Shungu’s consistent findings of increased lactate levels in the brain’s ventricular, Miller’s findings of basal ganglia deactivation, Hornig’s findings of altered cerebral spinal fluid cytokine, and Baraniuk’s altered CSF miRNA levels all suggested that neuroinflammation could be present but only the Nakatomi/Watanabe 2014 brain PET scan study directly found it.

Since then, the evidence for neuroinflammation in ME/CFS and its sister disorder, fibromyalgia (FM), has grown. Williams showed that a smoldering EBV infection may be precipitating a neuroinflammatory reaction in ME/FS patient’s brain. The brain metabolites and heat signatures Younger found were consistent with widespread neuroinflammation. Loggia’s PET scan studies found widespread neuroinflammation in both FM and Gulf War Illness.

Fibromyalgia, Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, Gulf War Illness – the Widespread Neuroinflammation Diseases

Yet neuroinflammation brain imaging studies in ME/CFS have been few and far between. Six years have passed since Nakatomi/ Watanabe’s PET scan study – hailed as a breakthrough – found evidence of neuroinflammation in ME/CFS patients. Tony Komaroff called the study the most important ME/CFS paper published in decades, but since then only Younger’s (combined) thermo-imaging (& magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS)) brain study has found direct evidence of neuroinflammation in ME/CFS.

This field is still too underfunded, unfortunately, to follow up even on potentially fundamentally important findings in a reasonable timespan.

Mackay and Tate called for more of a focus on understanding the “neurological pathophysiology” of ME/CFS and they’re not alone. Maes and Chaves-Filho recently postulated that microglial initiated neuroinflammation is at work in ME/CFS. Van Elzakker’s critical review asserted that the inflammation in ME/CFS is best studied in the brain, and Komaroff proposed inflammation was behind the neurologic issues in ME/CFS. Other prominent backers of a “neuroinflammatory concept” for ME/CFS include Drs. Shepherd, Bateman, and Ron Tomkins of the Harvard ME/CFS Collaborative Center. (Dr. Bateman proposed inflammation in the hypothalamus is key in ME/CFS).

Given Mackay’s interest in neuroinflammation, I asked him about the long wait to replicate the Watanabe paper. Mackay reported he’s been in regular contact with Watanabe, and that Watanabe has reported that not only will his larger cohort repeat study be published later this year, but that – working with the Karolina Institute – his earlier (2014) findings had been validated. (To Mackay’s delight, Watanabe also stated that inflammation in the hypothalamus had been detected.)

Mackay was probably not surprised. He’s been waiting for the neuroinflammatory face of ME/CFS to show itself for almost a decade. Both he and Tate believe that ME/CFS may be more akin to diseases like MS, Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimer’s than we know.

The Neuroinflammatory Disorders?

Mackay proposed that the same kind of (glial cell-activated) neuroinflammatory trigger that sets off the big nervous system diseases (Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, multiple sclerosis) may also set off ME/CFS. One hypothesis suggests while the neurodegenerative diseases have different initial triggers, all involve a common neuroinflammatory response (via hyperactive glial cells). It noted that:

“There is evidence for a remarkable convergence in the mechanisms responsible for the … amplification of inflammatory processes that result in the production of neurotoxic mediators” in these diseases: i.e. a common neuroinflammatory pathway exists.

The common link is neuroinflammation with different ‘in situ’ drivers (amyloid plaques in the case of Alzheimer’s) determining what the final disease state is. The “driver” – the neurological factor which drives the process in ME/CFS and FM – is unclear, but the potentially good news for ME/CFS is that contrary to other neurodegenerative diseases, the absence of overt nerve damage means it might be possible to reverse it completely.

There’s more good news. The authors pointed out that brain imaging techniques are improving rapidly. It was that improvement, in fact, which enabled researchers to first find evidence of neuroinflammation (in the absence of neurodegeneration) in ME/CFS.

Mackay believes better PET/MRI scanning techniques – including those used in the upcoming Watanabe paper- plus more funding, a critical need, could produce a diagnosable brain signature for ME/CFS/FM.

Mackay said he expected that the upcoming Watanabe ME/CFS study would feature more advanced PET/MRI techniques and more reliable and accurate results. The rapid growth of technology in this area and ‘the race’ to produce the best brain signatures for various diseases would, he thought, “clearly benefit ME/CFS and fibromyalgia research” as these techniques are being constantly improved, fine-tuned and refined (allowing even lower levels of neuroinflammation to be detected).

He ultimately envisions a quick diagnostic brain scan test may be available.

Meanwhile, the MERUK (ME Research UK)-funded Jarred Younger study that’s looking for immune infiltrates that could be producing inflammation in ME/CFS patients’ brains could be a game-changer.

Plus, the new OMF-funded Harvard Collaborative Center is putting a premium on brain imaging studies and Michael Van Elzakker’s ME/CFS brain imaging study is underway.

The paper didn’t refer to treatments, but the intranasals are one possibility. Jarred Younger, in particular, has been exploring treatments to turn down neuroinflammation using botanicals and drugs.

Dr. Klimas, interestingly enough, is doing clinical trials in Gulf War Illness and ME/CFS that aim to both reduce neuroinflammation (with etanercept) and reset the HPA axis (mifepristone). She will also be pairing an antioxidant with intranasal insulin in GWI.

Check out a long list of possible drugs and other substances including new drugs that are under development in Microglial Inhibiting Drugs, Supplements and Botanicals to Combat Neuroinflammation.

Does this theory explain PEM? Extreme exercise intolerance is the number one defining symptom of ME/CFS. A hundred other things may influence how bad I feel but nothing has a more profound effect than physical activity on me. When I was healthy, I would exercise for stress relief and the feeling of well-being so I’m not clear how even light activity would be stressing my system.

Thanks as always, Cort, for the updates.

I think it does. If I have it right it proposes that exercise – a stressor if there ever was one – causes the PVN to go bananas – and tell the glial cells to pump out pro-inflammatory cytokines and other compounds which then produce fatigue, pain, etc. It takes some time for the inflammation and the PVN to settle down – and then you’re back to SOSB eg. your baseline.

Yes Cort is correct – I propose that the PVN is the vulnerable “stress integrator” in the hypothalamus, in ME/CFS susceptibe people (like you, and me), which during the ongoing relapse-recovery cycles, if overloaded can result iin flare ups or relapses… and yes PEM too (a “mini flare up”), which occurs when you push it to that invisible ‘threshold/ tolerance level’ that tips the PVN into “twitchy, lost control mode” – could be most classically (like your case) by too much (intense) physical exercise (but it could also be by too much of other ‘stressors impacting your PVN – emotional, environmental e.g. too little sleep, too much chemical toxin exposure etc) – enough to cause the ‘malaise’ and ‘fatigue’ you feel with PEM (a “mini flare up”), but if you push it further, for sure you’ll induce a full flare-up/ relapse.

Omg, this has been happening to me for more than half my life. I suffer from pain, 5 herniations, terrible anxiety, depression, crying, fear. Suddenly it appears, I always say “ I have overdone it” or that is how it seems. Each time I begin to feel better, I try to start my routine again, it I step up my workouts, I eventually fall apart again. I have had all my kids here during pandemic and my son in law and 3 dogs. It has been stressful and wonderful. Now my daughter and her husband are moving away. I had been doing so well, doing harder workouts, losing weight, but working hard at keeping everything running smoothly. I had extreme pain, gut issues(always) , autoimmune thyroid disease, then suddenly full of anxiety, fear, depression. Then after a while, week, month, or more, suddenly the fear is gone. What is going on.? I’ve been on multiple meds but none of them have stopped it from happening g. So many doctors, so many diagnoses, vhigh viral tigers including EBV, Lyme.

This is amazing research Cort. I truly believe this type of research is going to explain this disease . The low hormones in ME can only be happening for one reason HP AXIS dysfunction.

Hi, Your research makes a lot of sense to me – CFS/ME is all about the big picture of Stress. I have had CFS/ME for the past 32 years, contracted at age 22. It is very obvious to me that Stress is the main trigger for a worsening of symptoms.

In my experience of CFS/ME, I define Stress to include all the following: – (small) adrenaline-rushes from any event; concentration; (over-) stimulation of the senses; digestion (of any but the most easily digested foods); emotion; (over) work & interaction with others; weather events (sudden pressure &/or temperature changes); and of course physical exertion.

I think physical exertion/ exercise, is the most easily comparable of all these bodily stresses between patients, and I believe focusing on this has made the other stresses we experience seem less important and even overlooked.

One note re my own experience: – my doctor, after many years, finally persuaded me to take Amitriptyline. So for the past 10 years I have taken a very low dose, 5mg a night, and I get a half-decent sleep – this makes all the difference to my day, as long as I have kept “The Stresses” in check too.

Great news that potential diagnostic is signature brain scan;

two more ‘bright lights’ in the field.

Have Mackay and Tate done any qeeg work or collaborations with qeeg researchers?

If so, did it reveal anything interesting?

Another question—

Cort, in your interviewing Mackay and Tate— did they mention any physical damage to the PVN that can be seen on post mortems?

Good question – not been done. In fact not enough ‘post mortems’ have been carried out on ME/CFS patients in general. If just inflamed it may not be easily detected in a ‘post mortem’ as with inflammation the damage is minimal (not like lesions and plaques visible with MS and Alzheimer’s, for example). Also the PVN is one tiny section of the hypothalamus – and Watanabe informed me that although they were detecting inflammation in the hypothalamus, as a whole, their PET/MRI was not sensitive enough to determine if the PVN itself was inflamed as well.

Hi Sunie, unfortunately not… Prof Tate is biochemist, whose research is mainly blood-based, and I too am a biochemist by my degree and training. My literature revirew and further delving into the ‘neuroinflammatory’ aspects of the disease has led me towards a growing interest in brain-imaging (PET/MRI, MRS, BRI thermometry etc), and were I to continue research at Otago Uni it would be as a brain-imaging ME/CFS reseacher… but if not, I will do my best to ‘sell’ the need for such desperatley needed research to the ‘brain research center’ at Otago Uni, Dunedin, NZ (and Cort’s excellent ‘blog’ will help in that quest, I think).

Thank you and best thoughts and wishes on your most excellent adventure.

Thanks so much for your work in wonderful Dunedin !! It’s very exciting for us NZers that NZ researchers are helping in the search for a cure for ME. Keep up the good work. best wishes coming your way from Chch

Hi Angus my name is Joan Burge and I live in Auckland I’m sick long term – diagnosed with chronic fatigue syndrome, Fibromyalgia, Hashimotos I had two surgeries for teeth removal and have never walked again unaided most of the time I now have pseudo seizures 8 years. Doctors don’t know what’s wrong and put it down to depression but I’m not depressed my brain shuts down and so does my breathing – can you help me in any way I would be willing to be seen for any trials or further testing! Regards Joan 61 years married female!

Hi, does having brain inflammation in fibromyalgia mean I will develop Altzeimers? My mother and her two brothers, my uncles, all developed it. Is there medicine for neuro inflammation? I’d rather take it sooner than later…. I too take amytriptyline 10mg at night which helps generally and 10mg omeprazole in the morning to help regulate IBS which arrived with fibromyalgia.

Hi Sunie, again no we are (blood) biochemists (Prof Tate has some experience with MRS for analuzing molecules in the blood, but not like Younger’s work on the brain itself), but I am interested in exploring some of these brain-imaging techniques more. EEG you mention is a method used to study “brain waves” by using sensors on the surface of the scalp, and there have been a number of those tried already with ME/CFS patients with varying results (but as we would have expected results that indicate not all is right within the brain of ME/CFS or FM patients). The problem is that ME/CFS patients brain functions vary so much by the hour/ day according to where they are within their own “relapse-recovery” cycle (maybe not the case so much with the 25% severeley ill bed-bound who are in a more steady bad state consistently) and could prove a better target population for such a study. However, my gut feel is that PET/MRI – Watanabe style- and the MRS (detects molecules like lacate) plus MRI-thermometry (detects small changes in heat i.e. inflammation) – Younger style are more likely to provide a more accurate picture and eventual “brain signature”…

In answer to Joan – there is no known drug therapy or cure yet for ME/CFS. Many therapies are put out there, but if they do help then the evidence at this stage is only “anecdotal” – not proven by scientific drug trials (double-blind placebo)… so the best way to “manage” your illness is to “pace yourself” and minimize any undue, needless “stresses” (impacting your hypothalamus!) in your life (easier said than done). Tate and I are research scientists interested in understanding how the disease works, and how it can be diagnosed accurately. I would recommend that you book an appointment with NZs premier GP on ME/CFS (witth over 5000 patients on her books) Dr Ros Vallings,in Howick, Auckland… best wishes.

Angus, thank you for your explanation.

maybe someplace like the NeuroCognitive Research Institute will get involved in research with the ‘severely sick’ and explore qeeg

in tandem with researchers

using imaging techniques you spoke of.

Fascinating.

I’ve always maintained that Jay Goldstein was on the right path with his ‘Limbic Hypothesis’ from the early 90s.

What a pity few gave that serious attention, until more recent times…

Yes, Dr Jay A Goldstein’s focus was on brain dysfunction/neuroscience and this followed his use of brain SPECT scans in 1989 with Dr Mena. They found a decreased blood flow to the brain in ME patients. At the time of his retirement in 2003 he was 25 years ahead. He wrote several amazing books and presented at many conferences but was mostly ignored. I was his patient. I travelled from Australia to see him. One of his earlier books was The Limbic Hypothesis and included images of the SPECT scans

Chronic Fatigue and Immune Dysfunction Syndrome (CFIDS) from the book “The Plot Against Asthma and Allergy Patients: Asthma, Allergies, Migraine, and Chronic Fatigue Syndrome are Curable, but the Cure Is Hidden from the Patients” (Felix Ravikovich, 2003):

“The functioning of the central regulatory systems and histamine’s involvement in it:

■the total body is not a mechanical construction made up of different isolated parts but an artful indivisible design of nature;

■ the functioning of the nervous, immune and endocrine systems is reciprocal;

■ the crossroads of these systems is the hypothalamus and pituitary unit — the brain structures controlling neuro-endocrine and immune mechanisms;

■ histaminergic neurons are abundant in the hypothalamus and only relatively less in the peripheral nervous system;

■ histamine is an inherent chemical in all body tissues and a major product of immunocompetent cells;

■ all cells possessing histamine receptors form the histaminergic system that conducts and realizes its messages;

■ histamine messages are central in allergy, asthma and are very important in other chronic immune inflammatory diseases; they also carry regulatory instructions to neurotransmitters in neurological disorders;

■ histamine messages work through the CRH/mast-cell/histamine axis and thus involve the HPA axis (CRH stands for corticotropin-releasing hormone)

■ histamine regulates CRH — the pituitary hormone-messenger, which activates the work of the adrenals, our main organ in adapting to all situations stressful to the body.

■ histamine imbalance can affect the functioning of the whole body due to the spread of histamine-generating cells and histamine receptors.

Since any functional encephalopathy arises as a result of a chemical imbalance in the brain, histamine’s ability to modulate the release of other important mediators and neurotransmitters may become crucial. Histamine governs

■ serotonin, which is central to the origin of vascular headaches, depression, chronic fatigue syndrome, irritable bowel syndrome;

■ norepinephrine, whose imbalanced release leads to depression, anxiety, chronic fatigue syndrome;

■ dopamine, whose release is central in schizophrenia and Parkinsonism, and

■ endorphins that affect mood and control any pain, including headaches.

The impaired regulatory activity of histamine becomes the cause for functional encephalopathies,including CFS.

https://www.healthrising.org/forums/threads/mast-cell-histamine-immunotherapy-with-histamine.6233/

I just added to Bayard thread, he linked above, some more information on carnosine. Appears it ups histamine in the hypothalamus. I can vouch for it helping me. My having severe MCAS (among other things, including ME), and trying to reset my H2R and H3R to work properly, is making a difference. Carnosine is also helping with muscle weakness and my sleep has improved. Also my memory is better. I just ordered another supplement that may boost this even further. I will report on that thread when I have experimented enough to see its effects.

Back to my core hypothesis of “Autoimmune dysfunction and Inflammation “. Pick your order.

Good to see more research in this field.

Hi Issie… glial cell overactivation is a form of autoimmune dysfunction, termed autoinflammatory (as not by WBC in blood but by more basic immune cells of the brain)… and their overactivty leads to inflammation (neuro-inflammation) is what I’m proposing i.e. both…

Hi Bayard – your reference and the role of histamine might help to fill in the “mechanistic detail” that is lacking in our “neuroinflammatory model” helping explain how an our of kilter “stress response integrator” (hypothalamic PVN) proposed in ME/CFS patients results in hyperactivated glial cells causing inflammation throughout the CNS, but particularly in the limbic system (to account for the array of ME/CFS symptoms)… or it may not?!?… Tate and myself ‘brainstormed’ some ideas – what we termed the “missing link” and suggested it might be a “virus lurking in the CNS”, or possibly linked to a “neuronal mitochondrial dysfunction – cauusing alarmins to be detected by glial cells, which become ‘alarmed’… or sommething else (I’ve read quite a lot about “neuronal-glial crosstalk” mechanisms – maybe these go awry in ME/CFS patients… all very conjectural/ theoretical at this stage – ultimately we need an “animal model” for ME/CFS to work out this detail… but until ME/CFS better understood we can’t (eg. genetically alter) an animal to replicate human ME/CFS… meanwhile persevere with brain/ CSF and blood studies to build up a holistic picture of what is going on…

Also appears to be dysfunction with glutamate and dopamine. Both of which can affect glial cells. And both closely connected together as for their function.

https://www.nature.com/articles/npp2016199

glutamate can profoundly influence the function of immune cells in the brain including microglia. Relevant to pathology, increased activation of the immune response in the periphery and CNS can lead to marked alterations in glial function and glutamate regulation, and through the activation of multiple avenues of excitotoxicity can lead to synaptic dysfunction and death,

Another possibly strong connection that can affect this too, is build up of acetaldehyde in the body. Dejurgen and I are researching this together and feel this plays a part in the dysfunction. (Not due to alcohol.) And histamine can play a part in “detoxing” it. (See links in this thread.) We have posted more information throughout Healthrising, when Dejurgen has felt it applied to the topics and he post most of our technical findings. (A search under his or my name should pull that up for you.)

https://www.healthrising.org/forums/threads/measured-high-endogenous-acetaldehyde-blood-levels-discovered-something.6126/page-2

https://jneuroinflammation.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12974-019-1652-8

These results suggest that DRD3 signalling regulates the dynamic of the acquisition of pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory features by astrocytes and microglia, finally favouring microglial activation and promoting neuroinflammation.

__________

In addition, there may be a build up of ammonia. Either due to methylation dysfunction or some other dysfunction causing an imbalanced build up. And this can cause dysfunction in balance in Glutamate and GABA……therefore, affecting function of autonomic nervous system and sympathetic vs. Parasympathetic function/balance.

http://fblt.cz/en/skripta/regulacni-mechanismy-2-nervova-regulace/5-neurotransmisni-systemy/

Some diseases such as liver failure may cause an elevation of blood ammonia levels. Ammonia as an uncharged species easily traverses the blood-brain barrier and in the presence of glutamate it can be converted into glutamine while consuming ATP. If there is too much ammonia, neuronal ATP may be depleted and at the same time two major neurotransmitter systems will be dysregulated – glutamate and GABA.

Hi Issie!

I’m a fan of yours –

I have hEDS and I have been suspecting that my type of it presents as the opposite of the hypotonia/weak aorta/mitral valve/thin corneas etc.

So that would be hypertonia, tight aorta/ thick corneas AND following, I’ve been wondering if maybe my blood vessels are also tight. I came across one of your comments, where you also suspect this is happening in you.

I think my connective tissue is not weak nor thin – it’s too strong and too thick. Both conditions are pathological, the hEDS literature recognizes only the first one (for now…)

And yet, the connective tissue in my joints is still lax. So is my skin.

Ammonia can also build up in some inherited metabolic disorders. It’s one of the screen test in newborns.

Also, low-carb high protein diet and high-exercise load can elevate ammonia levels.

For the same reasons, I think when your body switches to using energy from your muscles (proteins), that produces ammonia as well.

I often sweat ammonia. I have to make sure I eat enough carbs in a day to avoid this. I am not a high-exercise. Usually works, not always.

It did occur to me that the way my body makes its energy is wonky.

_Something_ is not getting processed right.

Which then, I wonder, does high plasma ammonia get excreted in the sweat also or…?

It seems yes:

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1396636/

@M, I’m glad you are finding benefit in what I write. I try to note when things seem opposite to the common way of thinking……as I’m always flipping a coin over to look from another side or angle. I think that is what it will take as the “common thought”, isn’t getting us very far.

You may also check to see if you have too thick blood. I do, and it is genetic too. They found too high Collagen Binding and Factor 8 with me. Also one time tested positive for APS. Thinning my blood has really helped. I do that with enzymes. And lots of my herbals help with vasodilating. I’m HyperPOTS too on top of EDS and MCAS. (And some other things…..) But that has been a big help to me to thin my blood. Helps with blood flow and oxygen carrying capacity when it gets where it needs to go.

Thanks for your comments and hope you find some “purple bandaids”!

@M, also look into methylation issues, especially CBS and BHMT issues. That can cause a build up of ammonia too.

Certain pathogens can add to it too. Things like h pylori, for example.

All of this is a huge circle that builds on itself and plays into each other.

Issie –

Yeeesssssss…

Posing the question that my muscle problem is a pathological one, as not just a ‘response of global muscles overworking to keep joints stable’ (the prevailing theory in hEDS literature) took me into a different path, one with possible treatments.

I strongly suspected a homocystinuria. Did amino acids plasma and urine tests recently. And nothing on that front. Though I think that CBS cannot be ruled out, because what I read in the guidelines is that if you only have one defective gene, methionine-loading test is the gold standard for diagnosis, (they administer methionine and take samples every so often after to see how my body processes it).

Methylfolate.. affects my muscle stiffness, spasms, nerves, and heart (!). So that’s the hyperPOTS, the extra norepinephrine, the over-active sympathetic system and the symptoms that come with that. Also, executive function is restored. can finally breathe. I don’t know about its sustained effect. I being careful, I don’t want it to be something that works at first and then stops, or causes other problems.

Have you tried it and if so, what has your experience been?

I did find something interesting: elevated B6. Tested twice, months apart, to make sure it was not a fluke. I asked around other people with hEDS and there were more than a handful. There may be more – how to know, if it is not something routinely tested? Which may mean: that particular form of B6 is not being synthesized properly. Some people were low, if I remember correctly. I can check on this.

B6 is a cofactor in many process in the body, (including glutamate at some point?). I haven’t really started to look at all the forms of B6 systematically, and cross-referencing with my test results. Most of my amino acids are borderline low, or normal-low. I wonder if that is why…

My taurine is low. Taurine is connected to heart and sodium/potassium balance. That’s my POTS right there. Though is it the cause of it or a result of it? I’d have to dig more.

AABA is on the higher side, interestingly.

I wonder if it could be the driver of muti-systemic symptoms in hEDS, wonky B6 synthesis…

What’s your B6 like?

Though I guess that something else could be going on with B6;

inhibited, or being used somewhere else where it is not supposed to

or..

CAn’t recall the details: they found a new genetic defect that replaces one amino acid from another in para-collagen chains one of the other types of EDS.

So who knows?

Need to sit down and study B6s…

are you familiar with this approach to MCAS (aspiring, potassium/sodium, quercetin. throw in some curcuma, vitamin c, etc)?

https://www.mastcelldisease.com/my-new-all-natural-rx/

@Meirav, yes I have looked into B6. The other more usable form is P5P. But I don’t want to get too far off the subject here or highjack its theme. I found P5P to actually send me into a sort of restless sleep, almost a “narcolepsy light” place. It for sure can cause vivid dreams. And that is with a tiny amount. I didn’t find it to be a good fit, in the end, for me.

I will say, some things that should have worked for me, backfired. And some things that should go into and work for dysfunctional pathways, get side tracked and don’t do as desired. I have a whole lot of issues with methylation pathways and the work around is tricky and not always successfully carried out. I’m trialing something else, right now, that may be a better work around on this. But too new on it, to comment just yet.

The Methylation subject is very complex and both dejurgen and I are exploring it.

Supplementing taurine, didn’t work for me, but supplementing something high in taurine did. I don’t use it all the time. That is Ox Bile. I hoped that the amino would work for me, but I must need assistors for it to be tolerated.

Dejurgen and I will eventually talk about what we are finding to be helpful. Still in discovery.

I can tell you are enthusiastic and jazzed”, keep that passion and keep searching……answers are out there……and we are getting closer.

@Meirav, forgot to comment on your link. Had not seen that. But I’m off my MCAS too. Trying to reset histamine receptors. Look on Healthrising forum under several threads, there is information on it. Bayard has a really good one dedicated to MCAS and histamine and Dejurgen and I have one with information on there too.

Wasn’t it Stephen Straus who said that HPA-axis was the main problem in ME/CFS?

20 years ago.

Treatment trials, please, for neuroinflammation…

Yes, there certainly is a lot of interest in this and treatment trials – with animal models and sometimes in humans are underway. One – Dr. Klimas’s etanercept – a neuroinflammation inhibitor + mifepristone trial is underway in GWI and ME/CFS and she will be testing other potential neuroinflammation reducers (an antioxidant plus intranasal insulin) in ME/CFS. Jarred Younger has a few studies in the works as well.

You can find a bunch of drug and other possibilities on this page – https://www.healthrising.org/treating-chronic-fatigue-syndrome/drugs/microglial-inhibiting-drugs-combat-neuroinflammation/. I also added a link to the blog.

Thanks for sharing this as always Cort.

Any inclination or hypothesis as to what treatment for neuroinflammation would look like? I know there’s been a few ideas thrown around but I truthfully forget.

Check out some ideas here – https://www.healthrising.org/treating-chronic-fatigue-syndrome/drugs/microglial-inhibiting-drugs-combat-neuroinflammation/. Hopefully, this is a growth field and more and more options will pop up over time.

There has been some success with low dose naltrexone (LDN) for fibromyalgia patients. Younger has postponed his LDN study on ME/CFS patients due to a lack of funding I believe. LDN is supposed to have potential glial cell activity supression qualities. I’ve tried it and had mixed results. The first time at very low does (1mg) it made significantly positive impact – I felt virtually better for about 3 months – but then the effect wore off and when I tried it again at the same or higher dose – nothing. CBD oils (the marijuana without the THC “high”) have also been touted as potential glial cell inhibitors, but when I tried them (3-4x) each time it did the opposite to what I wanted i.e. made my brain hyperactive and led to insomnia… and most recently a nasty flare up (Jan wiped out)… so just have to wait until there are some proper scientific trials and testing…

LDN for both myself and my sister, resulted in severe depression issues. It helped pain, but wasn’t worth what it did to us mentally.

And tweaking cannabidiol receptors wasn’t it for us either. I also found that increased brain fog considerably. PEA was the closest thing in that receptor family that I could use and it helps pain and gradually builds up to help more. But it too increases brain fog. The other good thing it does however is help with mast cell issues.

Tweaking opioid receptors has/had been my best help with both POTS and FMS and ME. (Though I’m no longer on that medicine either. And it too, increased brain fog.) But about a quarter to a half pill (lowest dose) of Tramadol was and had been the best result. I had to cycle on and off it to get that benefit. And had to stay really, really low on it for it to work.

There are some supplements that Dejurgen and I are trialing, based off of our experiences and what we are finding. And that has helped me more than anything else I’ve done. We are still in discovery and not ready to talk about what we are trying, just yet. We are finding that we are working on same things, but with different supplements. What he can use, I could not. But I found other supplements that worked on same thing, but a little before the step that his supplements do, in the pathways. So we are all different.

So are they any forms of treatment to help block the inflammation?

no not yet… as Cort says drugs being investigated and trialled by the like of Younger who is a “neuroinflammation proponent”… but nothing proven yet… The neuroinflammation is clearly of a differentkind to say a normal headache or migraine for which there are drugs available… but they don’t work with ME/CFS, and like any unnecessary additional “stress” on the bainn/ hypothalamus (PVN!) – I propose – they can even make you worse (PEM/ flare-up or relapse…)

When I have a nasty fibromyalgia (Neuro) flare up I take acyclovir 200mg 3x day for just a day, two if it’s very bad (headache, exhaustion etc) and it helps.

Cause or effect? Is the touchy PVN the result of something else? i.e. is it an effect rather than a cause?

If I understand this correctly, Mackay and Tate believe there is an as yet unidentified neuroinflammatory “driver” in ME/CFS – something that is activating the glial cells.

It must be difficult for a researcher. Do we work on the PVN, or do we continue to hunt for that unknown ‘driver’?

Correct Cort – I am proposing that a dysfunctional (suscpetible in ME/CFS people) is at the heart of causing the disease (various triggers target the PVN), and then perpetuating the disease via characteristic PEM, flare-ups and relapses… symtomps explained by inflammmation of limbic system and its hypothalamus – suggest you re-review our papers and look at the simple “neuroinflammatory model”…

Over thirty years ago Dr. James Jones, MD (a CFS researcher/clinician) told our ME/CFS support group here in Denver Colorado, that he believed that the body had a “stress thermostat.” His theory was that when the body’s stress level was exceeded, from any type of stress – physical, mental, emotional, environmental, etc. – that our symptoms were triggered and that we went into a shut down mode to protect us so we could rest and recover. It seems as if we are going full circle here with this based on information from Tate and Mackay.

I remember that – allostatic stress or load. Thanks for bringing that up. It does seem similar with Mackay/Tate focusing more on the brain and, in particular, one part of the brain. If Jones is still around it would be interesting to interview him and see what he thinks now after all this time.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23850395/?from_term=allostatic+stress+chronic+fatigue&from_sort=date&from_size=200&from_pos=2

Cort, A few years ago Dr. Jones left the CDC and came back to Denver to practice for a while. He was at the Children’s Hospital, immunology dept. Unfortunately he has retired. I have tried to locate him to speak to him, but cannot find any way to contact him.

But we rest and rest and rest for years, and don’t recover? Why doesn’t rest let us recover?

Following Mackay and Tate’s hypothesis – my guess is that the driver – whatever initiated the neuroinflammation in the first place – is still there – churning up trouble even when we’re resting. I’ll bet it’s inhibiting us from truly resting….

Correct Cort – I am proposing that once the hypothalamic PVN is “shocked” into dysfunction it is not “reset” by rest and so always vulenerable to any ongoing “stressors”… yes rest helps things to calm down, but the PVN is so sensitized that it sist their like a simmering volcano as ongoing “stressors” continue to converge on it. Sure “resting” removes “physical exercise stress” to some extent, but what about all the other “stressors” targetinng the hypothalamic PVN: emotional, financial, sleep deprivation/ lack of quality sleep, environmental e.g. chemicals/ toxins, noise, pollution etc/ infections/ vaccinations etc… they don’t go away with “rest” do they?

I love the volcano metaphor 🙂

Tanya, I’m responding to this comment because I can’t respond to your later one. To Contact Dr. Jones, I would suggest sending a letter to Children’s Hospital, immunology dept. with a request to forward, and add a note that the letter is regarding his research.

Good stuff Tanja, and my ideas build on the work of the likes of Jones and more laterly Drs Shepherd and Bateman as Cort has alluded to. But this is the first time an actual model has been produced to actually explain triggers, symptoms and relapses with a particular focus on the “stress response integrator” i.e. the hypothalamic PVN…

Does the hypothesis explain the study by Ron Davis’s team of removing ME/CFS cells from their blood serum and placing them in a heathy control’s serum to find that the ME/CFS cells ‘woke up’. Plus the finding of putting a healthy control’s cells in ME/CFS serum and finding they start to hibernate and behave like exhausted ME/CFS cells?

Also does the hypothesis explain the finding that nearly all ME/CFS patients tested for IDO1 or IDO2 has a mutation in the one of those genes?

Last I heard 76 out of 77 ME/CFS patients had that gene mutation

A gene that if not functioning properly can fail to regulate tryptophan properly

We’ll see how the Metabolic Hypothesis works out – the OMF has begun a kynurenine trial to check that out. I have no idea about that or what effect, if any, the IDOI and IDO2 mutations might have on brain functioning, but since the brain is such a master controller I imagine that a brain dysfunction could show up downstream with something off in the blood.

With regard to the brain, Ron Davis, the OMF and Ron Tompkins clearly believe the brain is or may be involved and should be studied as they are eager to get more brain imaging done at the Harvard Collaborative Center.

Hopefully, at some point we’ll see how all this ties together or doesn’t tie together.

Yes that’s right Cort – I think the “metabolic” changes (Davis et al…) we are seeing in the blood (which are too variable for a unique ME/CFS “blood test/ signature”) could be as a result of variable levels of inflammation in the brain/ CNS of ME/CFS patients – and if the hypothalamus is inflamed then it will likely affect the autonomic nervous system, which in turn could affect blood molecule such as immune cytokines and metabolites. It’s actually given a term and is in the literature for “stress related immune disorders/ changes” and is termed “psycho-neuro-immunological”…

I tried querying “kynurenine + paraventricular nucleus” on PubMed & GoogleScholar. I don’t see any *mind-blowingly revelatory* tie-ins but there are plenty of dots that are tantalizingly connectable (e.g. stress-induced epigenetic upregulation of TLR4 in the PVN).

If this first kynurenine trial goes well, hopefully it can be followed up with a similar study that includes brain scans before & after treatment. A concomitant decrease in PVN (or hypothalamus as a whole) inflammation would be nice to see.

A huge thank you, Cort, for your quality coverage, and to all the researchers.

Following up on my post from a few minutes ago:

The query “kynurenine + epigenetics” returned an intriguing result:

“Kynurenine, 3-OH-kynurenine, and anthranilate are nutrient metabolites that alter H3K4 trimethylation and H2AS40 O-GlcNAcylation at hypothalamus-related loci”

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-019-56341-x

I’m almost out of cognitive spoons and can only manage a clumsy skim, but it seems like supplementation with kynurenine led to changes in gene expression:

“Next, the results of RT-qPCR assays for 17 hypothalamic neuropeptide-coding genes revealed a significant, dose-dependent increase in gene expression (except of KISS1) in neurons supplemented with the three metabolites”

@Sean, here is a blog Cort did on Kyrenine pathways and there is a lot of comments and links tying that into inflammation and issues with glutamate. Which probably leads to a lot of the issues we deal with. It has been something I have been researching and thinking for about 8 years now. Before connections were even talked about with glutamate. Now more research is being done and tying it to a lot of other illnesses. Whether it’s a cause or just part of the puzzle, remains to be sorted.

https://www.healthrising.org/blog/2015/06/28/neuroinflammation-ii-the-kynurenine-pathway-in-fibromalgia-and-mecfs/

Back in 2013 on a POTS forum, we were discussing this as some were finding antibodies to GAD and having to use autoimmune treatments. I don’t process things in the channel correctly either. Had a serious ICU visit, because of it. Here is us talking about it there. It has been an ongoing interest of mine. And of recent, we have been getting more of the WHYs sorted.

https://www.dinet.org/forums/topic/22972-desperately-seeking-brainy-ones/#comment-214112

Thanks for this terrific piece.

I’ve always, always thought the heart of the issue, for me anyway, is neuroinflammation regardless of etiology.

In addition to cognitive dementia-like issues/mental fatigue, I have pretty significant POTS. I wonder if a similar mechanism could be at play in dysautonomias. Makes sense to me.

I’d say Yes. I have POTS too and it seems to all be interconnected.

Makes sense to me, Issie!

“In POTS, your autonomic nervous system (ANS- the nervous system in charge of automatic body functions) doesn’t work efficiently when you sit or stand up.” And I’m proposing that the ANS is dysfuncional due to an inflammation of its controlling gland – the master gland i.e. the hypothalamus… so yes, I woud say POTS is under the ME/CFS and FM “umbrella”…

… Symptoms wax and wane as the neuroinflammation increases and then dies down…

Speaking for myself, it never wanes, if not getting worse. I’ve just read the summary in the email. A research on a single case could hardly mean anything, even too stretch to be a meaningful hypothesis.

The idea that symptoms wax and wane doesn’t mean they disappear – it means they get worse when you crash and then get better as you get out of the crash.

You don’t experience crashes if you overdo it? You’re just getting worse and worse? Mackay proposes that the PVN can get more and more whacked out – taking longer and longer to return to “baseline”. (Baseline does not mean being healthy – it means your general state of health which is obviously different in ME/CFS than for healthy people.). If you’re getting worse it might never get back to where you were. I imagine that’s not uncommon if you’re on a downward spiral.

If you read the hypothesis you’ll see that it’s not built on a single study or a single case but on past research findings – as hypotheses often are. They seek to explain disparate data in new ways.

Correct again Cort.

In one of your recent blogs, Dr. Klaus Wirth hypothesized that dis-regulation of the RAAS system could explain a lot about ME/CFS. After reading this piece, I couldn’t help but think that both RAAS and HPA could be an entwined cause.

I found, although not totally applicable, a research paper linking aldosterone levels to HPA axis activity and wondered if there is a connection. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S014976340900102X

I was wondering if Mackay/Tate are considering RAAS/HPA relationship as well?

Hi Nancy, I see the HPA axis (and more so the ANS) being dysfunctional as a result of inflammation of the limbic system and specifically its hypothalamus. A dysfunctional HPA axis can possibly account for the often (but not consistently) hormonally regulated things e.g. low levels of blood cortisol found in ME/CFS patient (and higher rates of urination – kidney). A dysfunctional ANS – autonomic nervous system – the nervous system that regulates things like your gut motions (peristalsis), heart rate/ blood pressure, without you conciously thinking about it (i.e. subconsconsciously) can therefore account for common symptoms in ME/CFS like low blood pressure (which in turn might account for ‘orthostatic intolerance’ – feeling dizzy when standing up), heart rate changes, gut problems e.g. bloating, pains etc… Things like distorted temp reg, change in appetite, taste, etc. can all be accounted for by inflammmation of the hypothalamus (master gland) and other symptoms like fatigue, poor conc/ memory, low mood/ anxiety/ depression (I get in full blown relapse i.e. severe inflammation) etc. can all be accounted for by inflammation of the ‘limbic system’ of which the hypothalamus is an integral member of…

… So RAAS and a lot of other things mentioned in this blog like aldosterone and kyruneine pathways I perceive as also being “downstream” of the core inflammation in the brain/ CNS (glial cells are everywheere in the CNS)… what I am interestd in is what might be causing an inflamed PVN (hypothalamus) to induce glial cell over activation… what we term the “missing link”…

I am so grateful for their work. And I love unifying theories!

A quick diagnostic brain scan test — what we would give for this…

me too! But a simple low cost easily accessible diagnostic “brain scan” has to be fesaible as the technology continues to be refined and improved – the scanner would be a simple dome shaped helmet (bit like one of those “hair dryers” seen in at a hairdressers), and the scan could appear on attached IT screen instantly… why not?

So very interesting and encouraging.

I don’t actually have a diagnosis of ME/CFS because the medical profession, on the whole, don’t seem to really deal with it here in Ireland, as far as I know.

So, as they’re not much help to me I’ve had to try and figure things out myself. I mainly have brain and immune issues now. I used to be wired and tired (and had a bewildering myriad of issues) but I’ve managed to calm that vicious circle and now sleep really well.

Sleeping better and being less wired has also improved my tolerance of food and other issues.

My current focus is on maintaining energy to my brain, without setting my immune system off, including what I believe is brain inflammation. I’m determined to figure it out!

What I felt when I read this blog on the work of Mackay and Tate and the mention of all the other research in this area was – aren’t there some great people out there trying to work out this complex condition and I’m so glad they’re on our team!

Apart from having been very unwell, one of the worst things about this type of illness, is that few people understand it, or even believe it exists. I used to feel the need to try and explain myself to others, which really doesn’t work.

I think, for me, there’s a loss of dignity and self esteem involved. Now I’m reasonably well again and seem normal but I know that isn’t the whole truth about me and doesn’t reflect the effort it’s taken to get here.

However, all these intelligent, capable people from all over the world are focusing their attention in this area and are trying their best to help and that feels good to me.

http://www.irishmecfs.org/

Thanks Angus,

Yes, I’m aware of them and ME Advocates Ireland and I am a member of the Irish ME Trust, (imet.ie).

I am patiently and assertively trying to communicate to my polite but somewhat sceptical doctor, that my myriad of symptoms are real.

I think he’s beginning to realise, that the middle aged woman-itis, that he thought I suffered from, isn’t really ringing so true anymore.

However being in Ireland, the Health Service Executive (HSE), look at times, to the National Health Service (NHS) in the UK for research and so they were informed by the PACE study and the general psychological approach before that.

So I have carefully and calmly mentioned the apparent shortcomings of the trial and I could see he was listening…

I am aware that the PACE recommendations are under review and they were going to report in the autumn, this year. I don’t know whether this will be delayed.

I hope when the new protocols are revealed, that it may prompt a review of how patients are viewed and may give an opportunity to reveal the lack of consistent support, that researchers experience.

Ha ha! I love unifying theories too, Waiting.

This is brilliant. Thank you so much, Mackay and Tate.

I am so proud of the stickability of these New Zealand researchers. Results in this field happen when clinical plus research experience come together, but it takes a lot for senior scientists to really stick with the clinical reality and importance of the illness when they get so very little financial encouragement or academic Reward. The key ingredient seems to be a sustained willingness to align with patients.All the researchers noted here by Court have shared that commitment to Patients. Many have developed that commitment through their own or their families devastation. One of the problems in this field is that those who have the experience are too incapacitated to help, so more power to Tate and Mackay for teaming up and staying the distance.

To Dr. Mackay’s point in the comments above: “In fact not enough ‘post mortems’ have been carried out on ME/CFS patients in general” I would like to encourage all of my fellow pwME to enroll to donate their brains for ME research (when they are done with them, of course). Dr. Ron Davis notes, as have others, that having ME brains to study would greatly advance scientific understanding of the disease. An easy way to sign up is to start at http://www.braindonorproject.org. That organization will connect you with the most appropriate research lab. It is essential to register In advance of death. The process does not disfigure the body. Please join me in this effort to reduce the suffering for future generations.

I just signed up to their newsletter Ann – slightly nervous but it’s definitely something to consider.

Interesting hypothesis and thanks for answering questions about it here, Angus.

I can easily see how your hypothesis could explain a stressor such as exercise leading to a flare up of symptoms. What I don’t quite understand is how it explains the *delayed* flare up so typical of PEM?

Certain inflammation after excercise is delayed. IL6 for instance spikes up several hundred times (?) the day after a maximal exercise. It could be that this post-exercise inflammation is acting as the stressor signal to PVN. Hypothalamus is the nexus between acute inflammation and sickness behavior after all, and it could be over-reacting to low grade post-exercise inflammation as well in CFS patients.

Same thing could be happening with mental stress. A mental exercise stresses neurons and maybe there is a similar delay in inflammation for repairing the damage.

Excellent Q Salka – don’t know – you’re right there is a delay, we all experience between excess “stressor” e.g. too much (intense) physical exercise followed by a delay of a few hours + for PEM, and maybe longer 24 hours plus sometimes for a “flare-up” or worse a fully blown “relapse” – the bigger the “stressor” the worse the reaction from PEM to flare up to relapse… And so what could be causing the delays – well I can only suggest that there is maybe just some kind of “chain reaction” set off when a certain (PVN) “tolerance level/ threshold” is exceeded… which eventually eventuates in an auto- (neuro)inflammatory glial cell response throughout the CNS/ brain, but especially in the limbic system and its hypothalamus to explain the array of symptoms experienced by ME/CFS sufferers.

you can check this latest study wrt CFS/ME-

https://medicalxpress.com/news/2020-04-mecfs-patients-viral-immunities-devastating.html?fbclid=IwAR2u8yRvXg8WSrWJ-qzt53fYRP878hvXK0VcdfANO0B850t5muz-25bRGoc

In text from this article: “This provides an explanation for the common observation that ME/CFS patients often report a sharp DECREASE in the number of colds and other viral infections they experience after they developed the disease. Our work also helps us understand the long-known, but poorly understood link of ME/CFS to past infections with Human Herpes Virus-6 (HHV-6) or HHV-7″… Naviaux.

… a DECREASE is contrary to what i have read about ME/CFS nor what I have experienced, which is an INCREASE in susceptibility to colds and viral infections…

… This also connects ME/CFS to only one group of viruses HHV6/7, when there are mutiple “triggers” for ME/CFS – glanduar fever (EBV virus) being the most common, but also other triggers e.g. severe trauma, chemical toxin shock etc… so maybbe they are implying (as often the case) “subsets” for ME/CFS, but I thinkk it is more likely a “spectrum disorder”…

This is interesting Cort but it does not seem to deserve the hype that you are giving it. You have been reporting on nearly identical HPA models for a very long time now.

First, what makes this one any different to the others?

Second, without addressing the cause of the inflammation this belongs more in the realms of the scientific literature then here as it is only a partial picture that tweaks a set of partial pictures that came before it. I find this very frustrating and unenlightening.

I find your overindulgence of every little theory that comes along very frustrating at times. Where is the meat of it? The exciting new evidence? The extra value in this model over previous HPA models? The integration with the body of evidence?

You don’t always have to be excessively positive. Sometimes it is more benificial to point out the flaws in a model then its strengths. Leaving them out is, at the very least, unbalanced reporting.

The heart of the matter is that this model is yet another partial model that does not try to integrate all the available evidence nor does it create a novel testable hypothesis for new research. The one thing that you have pointed out more than any other is that it says that we should have more PET studies. That is so 2014.

If you had a reason for reporting this “new” theory other than the fact that it was “new” then I missed it completely. This is definitely one of your worst articles ever (hence my frustration and disappointment). I hope that I have been clear and constructive with my criticism. I am not trying to insult you, cause offence, or devalue the brilliant work that you do. I wish that I could do it!

I agree that there has been a focus on the hypothalamus. Dr. Bateman focused on the hypothalamus and inflammation at one time.

I could be wrong but this is the first published hypothesis, though, that I can remember which focuses on neuroinflammation and the hypothalamus, and in particular on the PVN. I had never heard of the PVN before, let alone in connection with ME/CFS.

The paper – which was published in 2018 – also provided a good opportunity to dig into and an update on the neuroinflammation findings in ME/CFS and FM – and to learn about the new Watanabe findings. It also provided me the opportunity to update the neuroinflammation drugs and supplements page. All in all that was a pretty good result for me.

I will get back to you on the rest.

Even if the idea that inflammation in the hypothalamus (and limbic system) has been proposed before the idea that a central stress integrator tucked into it presents real potential to me. I didn’t know before this that there was a central stress integrator in the brain. That was exciting at least to me.

Agreed – that there was no new evidence but this was a hypothesis paper -it wasn’t really designed to provide new evidence. It was designed to put the evidence there is together in a new way – and prompt others to explore it. Now we have the PVN – I get that didn’t float your boat!

Unfortunately, we are still at the beginning of exploring neuroinflammation in these diseases. An animal study in FM that recently came out actually proposes an interesting driver. Hopefully we’ll get more of that over time – enough to get both of us excited.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4688585/

This is a link to the article from Sleep Science, entitled Interactions between Sleep, Stress and Metabolism: From Physiological to Pathological Conditions.

In the Abstract they say ‘Sleep deprivation and sleep disorders are associated with maladaptive changes in the HPA axis, leading to neuroendocrine dysregulation’.

From their Introduction they state: ‘Sleep and stress interact in a bidirectional fashion, sharing multiple pathways that affect the central nervous system (CNS) and metabolism…’

They talk about the PVN (paraventricular nucleus) being connected to the central pacemaker of the circadian rhythm, the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN).

It’s a complex article but what I understood from it is that stressors can disrupt sleep and then sleep deprivation activates stress, including the HPA axis and the sympathetic nervous system.

I was definitely caught up in this vicious circle and it was having a very serious affect on my health. For me, dismantling the vice like grip between my chronically hyped up stress response and lack of restorative sleep was a fundamental part of my success in halting and reversing my downward spiral.

What I decided I had to do was prove to my ancient brain, (situated deep inside) that actually things were okay. (In reality they weren’t great – lone parent, not much money, chronically unwell with a weird illness no one believed in and with a family who thought I had mental health issues and an eating disorder). But I thought I’d just lie a bit because I had no other option.

I had been watching Dan Neuffer Videos online and decided I’d take a leap of faith and really focus on attempting calm my nervous system down and getting better sleep – using everything that I thought might work. Despite my doubts, I was successful. That was over a year ago now and I continue to make improvements.

Cort, it is simply not true that you had never heard of the PVN before reading this paper.

Here is an example written by you 5 years ago:

https://www.healthrising.org/forums/resources/adrenal-fatigue-the-real-story.108/

You kind of make my case. If it’s been five years – and over 500 blogs – since I’ve written about PVN I hope you can forgive me for not remembering it.

Some time ago I came across a blog on the internet. I started reading it, thought it was pretty good, looked up to see who had written it – and it was me.

I am really grateful for any focus on neuroinflammation. This is the scariest part of attacks for me. Fatigue, and not always present pain, I learn to deal with. Will consider brain donation.

Hi Kelly, before you make scathing comments perhaps you shoud read my (two) papers first and then make a more measured response. For example, you have said “nor does it create a novel testable hypothesis for new research”… but that is exactly what I have done – a neuroinflammatory model – “the model” in Cort’s piece which received excellent reviews (both papers), and in my papers (conclusions) you will see that my hope is that it will be used as a “framework” for discussion and research by ME/CFS (&FM) science researchers and as the reviewers remarked it is “de novo” as it centers for the first time on the hypothalamic PVN (stress reponse integrator) as being a potentially vulnerable point in the ME/CFS disease pathomechanisms and as far as I know it is the onlly “unifying hypothesis/ model” that can help to explain ALL the triggers, the full range of symptoms and characterisitic relapses for ME/CFS in such a “coherent and simple” way (reviewers comments)… Cort is correct – it is a “hypothesis” paper and it does select and integrate the relevant data (brain-focused work) from the (regrettably scant, yet mch needed) imaging studies available… Watson too also used other people’s results to produce a model (with Crick) for DNA, and his genius was beinng able to filter out the relevant from the irrelevant in his own modelling.

Why do we need a unified theory of ME/CFS? I had a little orthostatic intolerance when I first got ill 25 years ago and it cleared up 16 years later. Same for cognition problems. I had a lot at first and then 16 years later it all went away. Now, some 13 years later again, I just started to get some variable fatigue for some reason but no OI or cognition problems. Also the HPA axis dysfunction has been known about for years. This is nothing new. Although I used to get the shivers now and then my thyroid and adrenals were always completely normal and I tried taking thyroxine anyway once or twice for fatigue and symptoms but it never did any good. I therefore dismiss the theory. Sorry.

I would not say that the HPA axis dysfunction is really known. There have been a good number of studies, yes but they are all over the place – some address one part of the HPA axis and others address parts. It’s like the research in ME/CFS in general – stabs here and there but not nearly a complete picture. It keeps showing up in the literature. Nancy Klimas’s modeling efforts suggest it plays a key role. It’s not the only factor in ME/CFS – but it must be accounted for.

I think it’s more complex than we know – more than about thyroxine or adrenals. Klimas, for instance, is trying to use mifepristone – not thyroxine – to reset the HPA axis. Who do you know that’s taken mifepristone?

I wouldn’t count the HPA axis out just yet.

Could this be what’s going on with me for the last 30 years? I broke the windshield of my car with my head. I have never been the same. If I do too much when I am feeling more normal, I go into some kind of flare, depression, anxiety, pain, fatigue, etc. to much stress of any kind caused it. I have searched for answers. Many drs. Chronic fatigue, fibromyalgia, Lyme and I do have Hashimotos. Exercise seems to be one thing that is difficult to keep tolerating. If I step it up, I will be ok for awhile but then break down again. Help

Ron Davis is only interested in making money himself. I asked him about his uptodate RBC deformability research and whether this has been proven to happen in CFS or not because an Australian study found no difference apparently I read somewhere. So who is right? ROn or Aussie? Yes or no? So I said I know a measurement company in rhe UK who could measure RBCS possibly and see if they could find out the answer. He did not even bother to reply to me and I even sent his research fund $20/ So my impression from over here to over there is that Stanford uni don’t want to share anything with anyone. I also can’t see what the point of the impedance test is going to solve.

I’m not really impressed with the output/results from OMF relative to the amount of funds going to them either. I have little faith they will be the ones to make a significant breakthrough.

I feel the same way about OMF seems like Davis is running in circles . From my personal experience of ME I know its my brain causing my disease . HP axis has been identified as the leading cause of low cortisol for decades this is nothing new . It seems pretty obvious to me that the master controller /brain is no longer telling the endocerine system to function properly leaving us extremely ill mainly due to adrenal insufficiency . What I find interesting is that you can see that people with adrenal diseases are suffering from the exact same symptoms as people with ME. They even wear the same things like headphones and sun glasses in there houses etc. The diseases are so similar except people with ME don’t get treatment for there low adrenal function and are left for dead which seems insane to me .

Martin I would like to challenge your conclusion that because Ron didn’t answer you that he “only interested in making money” or that if he didn’t answer you that that means he doesn’t want to share. He gets lots of requests and is very busy – that makes more sense to me.

I imagine Ron could very easily have gone into industry and made tons of money. Instead he’s chosen to maintain his academic position and do what he loves to do – which is to do science.

Could someone comment on how this theory relates to the limbic theory underlying the Cortene trials?

Hi David, good question and I have been in touch with the Cortene team and asked them your question in effect too, but yet to hear back from them… There are some differences – they beilieve (I think) that the key stress response system affected in ME/CFS is not within the hypothalamus it self, but another part fo the limbic system… if they are correct, it could be, therefore, that what I perceive as a potential “bottleneck/ vulnerable point” i.e. the PVN (hypothalamus) because that is what all the “stressors” that impact on ME/CFS appear to target (converge upon) initially – it might be that the PVN simply “shunts” the stress signals onto the Cortene proposed site in the limbic system… The other difference (i think) is that the Cortene explanation for brain dysfunction is different to and does not involve glial cells which is at the core of my proposal (as it was when my ayes lit up at the results of Watanabe’s 2014 MRI/PET study)….

Very helpful. Thank you!

@Angus Mackay and Warren Tate:

Thanks so much for diving in deep. I much appreciate that. I also am a strong believer that modeling this disease is a major part to breaking it.

I am a bit late replying as I crashed myself in trying out some ideas lately so I hope you still get this. I still have to read the paper itself but I wish to reply before this blog has died out.

Issie and I are working hard lately at trying to figure out some detailed biochemical and physical pathways helping explain our disease(s) better and are moving forward beyond our own expectations.

Our efforts so far link large parts of this disease as well and help us explain plenty of events we experienced due to this disease in unexpected ways. We also do find strong links with diseases like Parkinson, MS, AD… with the difference that our “inhibition / Dauer down” might actually be a major part of a mechanism largely protecting us from these pathways turning into permanent damage.

There is far more to it, but derailed blood flow, inflexible RBC, intermittent local (near the finest capillaries) hypoxia and reperfusion damage, inhibition of oxygen delivery from RBC and oxygen uptake by mitochondria in a protective effort and buildup of plenty of ROS and a variety of toxic aldehydes strongly interfering with the dopamine and histamine system seem to be major players at work.

This IMO does not compete with your work, but might provide a fysio-chemical link or set of pathways that help both set up this

PVN to go haywire and create much of the vicious circle in keeping it haywire.

Our main goal is not fame and career but fighting back at this disease. If interested in any of these ideas, feel free to contact me at the message part of the forum under user dejurgen or follow up what will come out of this effort. In due time we hope we can wrap things up in a more clear way better supported by science.

It does give new insights in some of the quotes below.

“Does this theory explain PEM?”

“What I don’t quite understand is how it explains the *delayed* flare up so typical of PEM?”

“Tate and myself ‘brainstormed’ some ideas – what we termed the “missing link” and suggested it might be… …maybe these go awry in ME/CFS patients… all very conjectural/ theoretical at this stage”

“Does the hypothesis explain the study by Ron Davis’s team of removing ME/CFS cells from their blood serum and placing them in a heathy control’s serum to find that the ME/CFS cells ‘woke up’. Plus the finding of putting a healthy control’s cells in ME/CFS serum and finding they start to hibernate and behave like exhausted ME/CFS cells?”

Kind regards,

dejurgen

Let me share beneath (the to this blog relevant part) of our (Issie’s and my) current line of thoughts. Note this is a quick write up out of memory without the usual extensive cross checking we do so it could contain some inaccuracies.

However, as far as memory serves all of the following beneath this comment has backing by scientific papers.