Check out Geoff’s narration

The GIST

The Full Blog

Effort what?

Ah, the famous (infamous?) NIH Intramural ME/CFS study. Interrupted by the pandemic and dramatically downsized, the “Deep phenotyping of post-infectious myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome” study was still one of the most expensive, and certainly the most comprehensive ME/CFS study ever done.

THE GIST

- Interrupted by the pandemic and dramatically downsized, the NIH Intramural study was still one of the most expensive, and certainly the most comprehensive ME/CFS study ever done. Nancy Klimas said the study was, “As thorough an evaluation as has ever been delivered in any clinical study that I know of in any disease”. Avindra Nath, the leader of the effort which ended up involving over 75 researchers, said it was easily the most complex project he’d ever led.

- Its findings were gobbled up by the media, and in the media the reports were, in fact, overwhelmingly positive, but many in the ME/CFS community greeted the findings with alarm. Something called “effort preference”.

- Walter Koroshetz, the Director of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), spent much of his introductory talk not on explaining what the study was about but on effort preference. He explained we tend to think of effort as something we consciously assess, but when neurologists use this term, they’re referring to microsecond-by-microsecond decisions by the brain which are below our consciousness.

- When our muscles just can’t go any further, many times it’s not that they’ve run out of energy but that in a process called “central fatigue”, the brain has told them to stop. The study findings suggest that something has gone wrong with the pathways in the brain that tell the muscles to move.

- Avindra Nath spoke of his deep commitment to solving this disease, and citing all the controversy, asked for a bit more trust. In my experience, Nath has been open and available and has supported this disease in many ways. We lucked out when we got Nath.

- Nick Madian emphasized that effort, as applied to their work, is not under conscious control. The brain evaluates whether to move forward based on the amount of energy spent and the “reward” it sees is available. If the cost-to-benefit ratio of an action is low, the brain will send messages in the form of fatigue, difficulty moving etc., to make sure the activity is not carried out.

- Most interestingly, this process is carried out in the brainstem, which is the locus of so many other things – from sensory to autonomic nervous system problems – that are at play in ME/CFS. The brainstem regulates movement, in part, by the generation of norepinephrine – which we will see is low in the cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) in ME/CFS. Norepinephrine activates pathways in the “evaluation network”; if the evaluation network says no, it will be very difficult to move. Again, these pathways are not under conscious control.

- Parkinson’s Disease, stroke, dementia, and brain damage can all affect the evaluation network in similar ways as ME/CFS, and Madian noted that dopamine-enhancing drugs help Parkinson’s patients to “engage with physical tasks more readily”.

- Since it’s the motor cortex that tells the muscles to move it, the motor cortex was checked out, but both it and the pathways in the brain that engage it were found to behave normally. Activity in the temporal parietal junction pathway, though, which assists in “motor control” and “motor control signaling” was reduced.

- In the end, reduced levels of norepinephrine, dopamine and serotonin in the cerebral spinal fluid were believed to contribute to the loss of “motor control” and the inability of ME/CFS patients to exert themselves. Norepinephrine, in particular, was signaled out because of the crucial role it plays in movement and in maintaining brain energy levels. In the end, the problems are believed to start in the brainstem and the hypothalamus – two areas that are already of high interest in ME/CFS.

- In the immune system, multiple check points that are required to activate T and B cells were found, as was T-cell exhaustion. The inability of these later or adaptive immune cells to track down and kill pathogens or pathogen infected cells could be causing the activation of the more primitive, less effective and highly inflammatory innate immune system that is seen in ME/CFS. Dr. Nath suggested drugs that could help.

- The gut flora of the ME/CFS patients was less diverse and lower levels of butyrate producing bacteria were found. Both of these have been seen before in ME/CFS and work is ongoing to further explore these findings. Interestingly, low butyrate levels were also found in ME/CFS patients’ cerebrospinal fluid.

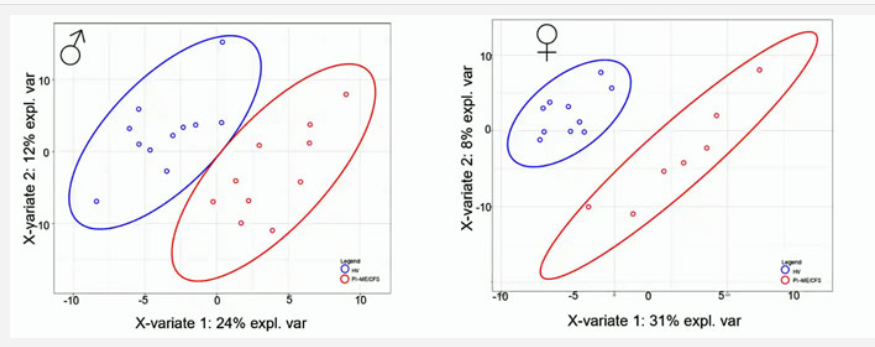

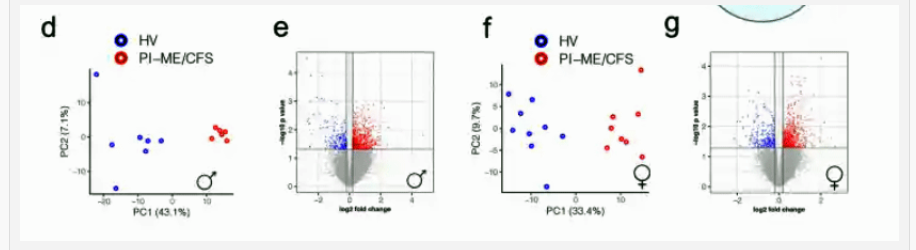

- The molecular biology or “omics” studies demonstrated how important it is, in this very important arena of research, to separate males from females. Every time this was done, dramatic differences were found between the healthy controls and the ME/CFS patients even when the sample sizes were very small.

- Once again, this study validated past findings in ME/CFS, including problems with fatty acid oxidation, mitochondrial functioning, lipids and proteins.

- The exercise physiology study found that people with ME/CFS were unable to generate normal amounts of energy to the extent that “performing activities of daily living would be difficult”. No increased incidence of postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) was found, in part because similar numbers of the healthy controls tested positive for POTS. (You can have POTS and still be healthy.)

- Post-exertional malaise is being explored in further studies.

- Ultimately, the authors proposed that an infection leads to immune dysfunction and changes in the gut microflora, leading to impacting the brain, leading to decreased production of catecholamines (norepinephrine, dopamine, serotonin), which disrupts autonomic nervous system functioning and impacts the ability to exercise. A wonky hypothalamus results in decreased activation of the temporoparietal junction when people with ME/CFS try to move. That results in reduced engagement of the motor system, problems with movement and ultimately, exertion.

- The dataset from the study is available to anyone. I counted at least 8 ongoing studies within the NIH that have resulted from this work.

- Several severely ill people who participated in the study spoke, including one person who had to be carried on a stretcher, and another who could not sit upright for 15 minutes without severe symptoms. They all lauded Brian Wallit and his team for their attention and care.

- Despite all the angst and controversy the study findings first aroused, this study was clearly a significant success for the ME/CFS community. Despite its reduced size, it achieved its goal of providing numerous openings for future research, and it suggested that, if done right, ME/CFS is very amenable to study even when small sample sizes are present.

- Past findings were validated (B and T-cell abnormalities, T-cell exhaustion, brainstem abnormalities, mitochondrial issues, low HRV, low gut butyrate, low gut diversity, lipid abnormalities, reduced energy output, reduced dopamine, gender effects) and promising ones popped up (temporal parietal junction functioning linked with poor motor performance, reduced CSF norepinephrine and butyrate levels).

- The reduced CSF norepinephrine findings appear to present a particularly enticing finding as the low norepinephrine production in a potentially critical area in ME/CFS – the brainstem – could affect not only the effort/reward/movement issues found but also brain energy levels.

- Even the researchers seemed startled by the large separations between healthy controls and ME/CFS patients that showed up once gender was taken into account. These findings suggest that simply separating the genders in future studies (or by reassessing past study results by taking into account gender) could be very helpful indeed.

- Several panelists at the symposium, including Dr. Nath, declared that it was time for clinical trials to take place.

Its findings were gobbled up by the media, and in the media the reports were, in fact, overwhelmingly positive, but many in the ME/CFS community greeted the findings with alarm. Something called “effort preference” reared its head, and how was it possible that there was no evidence of increased postural orthostatic tachycardia (POTS). How could that be? This, some concluded, was nothing more than an attempt to push ME/CFS back into a psychological corner. Avindra Nath was all over the media stating that the effort preference finding was not a psychological one, but the damage was done.

We weren’t done with the study yet. The Symposium that followed the study gave the investigators a chance to tell the study’s story in their own words – and they told a different story, indeed.

NINDS Director Walter Koroshetz spent much of his introductory talk explaining that effort preference did not refer to a conscious process.

The Symposium on the Intramural Study

It’s not clear when the Symposium of the NIH’s Intramural Study was planned, but I wouldn’t have been surprised if it didn’t start within days of the study’s publication. The NIH – to its credit – didn’t simply shut up and go away: it took the time and trouble to produce a symposium to clarify the study’s findings.

The study presented many intriguing findings, most of which were in line with what we know about chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), but the finding of “effort preference” and the way it was (or rather wasn’t) explained overshadowed all. There may be no better example than the “effort preference” finding of how badly the meaning of a scientific term (sickness behavior is another one) can clash with a layman’s understanding of it.

How big of a problem was the effort preference issue? Walter Koroshetz, the Director of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), spent much of his introductory talk not on explaining what the study was about but on effort preference. If you were upset about the finding – and most of us were – your voice was heard.

Director Koroshetz reported that the word “effort” has connotations in the press that don’t apply to neurology. We think of effort as something we consciously assess, but when neurologists use this term, they’re referring to microsecond-by-microsecond decisions by the brain which are below our consciousness. The whole thing is happening too fast for us to be aware of any of it.

Every time we move, that brain computes – based on a number of factors including the potential reward gained and the effort required to get that reward – how it will deal with the muscles. You would think that if, say, during a handgrip test, you got to the point where you couldn’t go any further, that would indicate that your muscles had pooped out. If you electronically stimulate the nerve at the muscle, though, the muscle will start to contract again. This indicates that a significant part of the fatigue we experience is “central fatigue”; i.e. something in the brain is stopping the muscle from exercising (contracting).

It’s a computational problem that involves reward and effort than anything. We’ll be getting into how terribly important and intertwined the reward system is and how it appears to be impacted in ME/CFS and similar diseases in another blog, but suffice it to say that the whole idea of “reward” is determined by microsecond-by-microsecond calculations in the brain, below our level of consciousness.

The findings suggest something has gone wrong in the circuits of the brain that have to do with reward, effort and movement (and there’s quite a bit of evidence to suggest that).

Avindra Nath spoke of his deep commitment to solving this disease and asked for a bit more trust.

For his part, the leader of the project, Dr. Nath, bared his soul a bit in his introduction, stating that:

“we’re deeply committed and have a strong conviction to treating this illness and finding cures for this disease…(that) we’re your partners and have the same shared goals”. However, “when you doubt our intentions and pick apart every single word, you also tear us apart. It causes pain and suffering on both sides and demoralizes us and shatters our goals.”

This is the second time that Nath has alluded to the demoralizing effect that attacks can have on researchers. (The first had to do with efforts to remove Brian Walitt, even though Walitt was administering the study – not doing the research.) Researchers may be analytical in the extreme, they may love to play with numbers and concepts – but they are still humans.

Certainly Nath has earned our respect and trust. Nath, who is involved in many different efforts besides ME/CFS, has been as open and available as anyone I can remember. He has gone above and beyond by repeatedly advocating for more ME/CFS research and has made every effort to link ME/CFS with long COVID in the press. We could have gotten a wallflower who disappeared into his office. Instead, we got a good communicator and supporter. We lucked out when we got Nath.

Still, on the ME/CFS side, the words “effort preference” were bound to raise hackles – there was just no way that was not going to happen in a patient population that has been fighting against being psychologized for decades. It’s unfortunate that the NIH couldn’t somehow find a way to get the word out ahead of the paper.

The Effort and Central Nervous System Findings

A recently retired Dr. Hallet led the discussion of the central nervous system results. Hallet was a senior, highly respected researcher and just happened to be an expert in one of the main findings of the study – problems with “motor control”, as well as movement disorders. Three of the other presenters – Dr. David Goldstein, Dr. Horowitz, and Dr. Snow – were described as “senior researchers”.

Effort!

Nick Madian covered the touchy effort topic. Echoing Koroshetz, Madian emphasized that effort, as applied to their work, is not under conscious control. Yes, during exertion we can gin up our effort, but in the final rung, it’s ultimately the brain that decides how far an effort will go. The brain makes that decision based on the amount of energy spent and the “reward” it sees is available. If the cost-to-benefit ratio of an action is low, the brain will send messages in the form of fatigue, difficulty moving etc. to make sure the activity is not carried out.

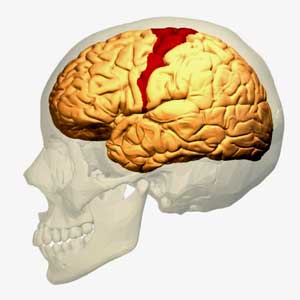

Low levels of norepinephrine in the cerebral spinal fluid may turn out to be important. Norepinephrine is produced in the locus coeruleus in the brainstem. (Image – Diego69 WIkimedia Commons)

The brainstem (once again, the brainstem) regulates movement, in part, by the generation of norepinephrine – which we will see is low in the cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) in ME/CFS. Norepinephrine then activates pathways that are involved in evaluating the cost/benefit analysis: i.e. is movement or activity called for or not? If the evaluation network says no, it will be very difficult to move. These pathways, again, do not appear to be under conscious control. Parkinson’s Disease, stroke, dementia, and brain damage can all affect the evaluation network.

Madian used a test that’s used to study effort in neurological diseases and found differences in something called “effort discounting” in ME/CFS. Effort discounting refers to the process by which rewards seem less rewarding the more effort we put into them. While the people with ME/CFS put as much effort into the tasks as the healthy controls, the rewards dimmed more quickly for them.

The most significant thing about that finding was that the increased effort discounting was strongly positively correlated with the low cerebral spinal fluid norepinephrine levels found. The lower the norepinephrine levels the more strongly the rewards dimmed for the ME/CFS patients – and the more effortful the task became. (Note that norepinephrine levels in the body; i.e. the plasma were normal.)

Madian took us even further from a psychological interpretation of the effort preference finding when he reported that the same pattern is found in Parkinson’s Disease. He noted that dopamine-enhancing drugs help Parkinson’s patients to “engage with physical tasks more readily” and reiterated that none of this is taking placed at the conscious levels. He proposed that the disrupted effort discounting may be related to post-exertional malaise.

Motor Cortex

The motor cortex directs the muscles to move. It is not the problem in ME/CFS, though. Something in the pathways leading to the motor cortex is.

Dr. Bedard explained that the motor cortex in the brain sends messages to the muscles to move. At some point, the muscles will get tired or fatigued. He used magnetic stimulation of the motor cortex to determine whether the fatigue was coming from the brain or the muscles during a hand exercise test. If the fatigue was coming from the brain, the response to the stimulation should die over time. If it was coming from the muscles, the muscles should show an increase in low-frequency electrical activity.

Both groups – ME/CFS and healthy controls – showed a similar maximum generation of force, but the ability of the people with ME/CFS to maintain that force declined over time. The declining excitability of the motor cortex in the healthy controls, combined with few changes in the electrical signals in the muscles, indicated that the central fatigue was driving the fatigue in their muscles.

The increased excitability of the motor cortex over time in the ME/CFS patients – but no changes in electrical signals coming from their muscles – presented a very different situation. The hyped-up motor cortex should have been driving more signals to the muscles, and their muscles still appeared able to generate force, but the people with ME/CFS’s ability to maintain that force dropped dramatically.

Silvina Horowitz took it from there. Seeing the increased motor excitability – but no signs that it was helping people with ME/CFS exercise their muscles – she used a functional MRI (fMRI) to check out what was going on in the pathways of the brain. The pathways in the brain that engage the motor cortex were normal – it was being normally engaged – but the temporal parietal junction pathway, which assists in “motor control” and “motor control signaling”, was reduced.

Later, we heard that more work was being done to combine the different brain modeling data points to understand what’s going on. More “connectivity analyses” to understand what’s going with the norepinephrine production involved are being done as well.

Dave Goldstein, the Director of the Autonomic Section, was up next. He did not find evidence of increased postural orthostatic tachycardia (POTS) in ME/CFS – in part because he found fairly high levels of it in the healthy controls. (It’s possible to have POTS and be completely healthy.) The neurotransmitter tests were, however, quite revealing. As noted earlier, norepinephrine levels (measured using DHGP) were “quite decreased” in the cerebral spinal fluid of the ME/CFS group.

Norepinephrine, dopamine and serotonin levels were all altered. Hallet suggested that low norepinephrine levels could be reducing brain energy levels. (Image Nippapag Wikimedia Commons)

In his summary of the session, Dr. Hallet reiterated that the central fatigue problem in ME/CFS was not coming from the motor cortex but from other “drivers”. He pointed a finger at the reduced levels of dopamine and norepinephrine, and also noted altered serotonin levels found in the cerebral spinal fluid.

Dr. Hallet then suggested that the altered CSF catecholamine levels may be affecting brain metabolism and energy production. Noting that neurons need lactate and that norepinephrine helps transport lactate to the neurons, he proposed that the low norepinephrine levels found in ME/CFS could be reducing energy production in the brain, causing problems with cognition and autonomic nervous system functioning (!). The norepinephrine/energy connection was entirely new to me.

(Interestingly, in the end, it comes down to poor mitochondrial functioning – not because the mitochondria are broken – but because they’re not getting the energy substrates (lactate) that they need to function properly. The problems with fatty acid oxidation, and the switch to using amino acids to power the mitochondria in the body, suggest that a similar process – an inability to properly feed the mitochondria – may be going on in the body.)

Hallet then proposed that it all starts in the brainstem and hypothalamus. What caused those two brain organs to fail in this manner was not clear, however.

Immune System Exhaustion

Multiple set point defects on B-cells resulted in problems with switching from IgM (the early responder) to IgG antibody (the later responder) production – a problem that can result in T-cell exhaustion – which was found. (Checkpoints of T-cell activation were disrupted as well). This isn’t the first-time immune system exhaustion has been found, and with Nath’s proposal that immune clinical trials get started, it may be that enough evidence has been found.

Immune cell exhaustion was found again. Is it time for clinical trials?

With the adaptive immune system (T and B-cells) reeling, the early or innate immune system jumps in. The innate immune system, though, is designed to hold the fort for the adaptive immune system – not to get rid of pathogens. It’s highly inflammatory and non-specific; i.e. it can’t really hone in on specific pathogens or pathogen-infected cells and is destructive when over-used. An overactive innate immune system could be causing a lot of mischief in ME/CFS.

The low levels of the less abundant gut bacteria that were found in ME/CFS (reduced microbiome diversity), and the low gut butyrate levels, aligned with the results of past ME/CFS studies. The person presenting noted this is just the beginning of the gut analyses that are underway. Three more papers are underway which will link the gut findings to other findings from the study. Importantly, they will attempt to determine if the gut is influencing other parts of the body or vice versa.

The Omics Studies

Again and again, we saw huge separation in the omics studies when men and women were assessed separately.

It was in the molecular biology, or OMICS, studies that the importance of separating males from female really stood out. In some ways, this was the most impressive part of the study because even though the study numbers were generally quite low, once the researchers separated the male from the female patients, the contrasts between the ME/CFS patients and healthy controls were remarkable. This indicates that, despite its vaunted heterogeneity, ME/CFS is actually VERY amenable to study once it is studied correctly.

The presenter referred to the “enormous separation” found in an immune analysis which found, rather remarkably, the same cells – B-cells – being altered in ME/CFS but in different ways in men and women.

When it came to the proteomics analysis, the presenter stated, “when we separate by men and women, wow, that’s a lot of separation!”. The same exclamation came with the muscle analysis, “When we separate by the men and women, wow, that’s a lot of separation!”, and, “We see again wonderful separation in men and women”.

Even in very small studies, we see evidence of a large difference between the genders.

“Separation” is what researchers live for. A lot of separation in the results between people with a disease and controls suggests they’re really onto something. Many times, we see results with a lot of overlap, but not this time. The OMICs research group was surely jazzed by what they found.

With regard to metabolomics, they saw downregulation of the beta oxidation network and mitochondrial processing, and in the women, beta oxidation upregulation and down regulation of fatty acid processing in the mitochondria.

The same pattern – a dramatic difference between patients and healthy controls when gender was taken into account – showed up in the metabolomics study of the cerebral spinal fluid. (All ME/CFS patients also showed alterations in glutamate, polyammine (???), and TCA (aerobic respiration) metabolites, implicating the arginine pathway and branch chain amino acids.) Nath noted that getting more ME/CFS cerebral spinal fluid was critical, and there are many analyses that can be done on it.

The gut got more interesting when we found that butyrate was low in both the gut and in the cerebral spinal fluid (CSF). Because butyrate is only made in the gut, and because it has anti-inflammatory and anti-demyelination properties in the CSF, the low butyrate levels in the gut could be making way for increased inflammation in the central nervous system. Butyrate is now being studied in neuroinflammatory diseases like Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s.

When asked, the presenter could not say that butyrate supplementation would help. The gist was it’s probably far better to find a way to induce the gut to produce butyrate than in trying to supplement it.

These findings suggest that when get to the molecular level, it indicates that men and women are quite distinct, and makes one wonder how many problems have been hiding in plain sight that could have been uncovered by separating out the men from the women.

The presenter concluded, “everywhere we looked (the gender split appears) to be of profound importance in understanding the nature of ME/CFS”, and pointed to the cerebral spinal fluid metabolomics results which highlighted the central nervous system.

BioEnergetics

Exercise physiology – the exercise study found widely variable results, with some people with ME/CFS performing well and others not performing well. In general, people with ME/CFS were unable to generate normal amounts of energy to the extent that “performing activities of daily living would be difficult”. They did not find problems with low CO2 or oxygen saturation of the muscles but did find a lowered heart rate response (chronotropic incompetence).

The metabolic chamber did not show problems with CO2 or altered energy expenditures while resting or sleeping.

Body fat – Sam Love presented on the DEXA scan, which measures the whole body fat, lean body mass and the amount of visceral fat around the organs. This is potentially important because of the inflammatory nature of the visceral fat found around the organs, which can lead to numerous health problems. People who seem lean can still have high levels of visceral fat. It’s something you really want to avoid and, in this case, the news was good. While there was great variability – which was expected – people with ME/CFS did not differ significantly with regard to whole body fat, lean body mass or visceral fat levels.

Paul Hwang spoke about the WASF3 finding which Health Rising reported on earlier. In a complex study, Hwang found increased WASF3 production, which may be able to disable the mitochondria, and which suggests a treatment strategy.

Autonomic Nervous System

Mark Levin, a cardiologist, found a trend toward reduced sympathetic activity with increased heart rate during the day and a reduction in parasympathetic activity at night in people with ME/CFS. A decrease in baroslope and longer blood pressure recovery times after the Valsalva maneuver in PI-ME/CFS indicated decreased baroreflex-cardiovagal functioning.

Post Exertional Malaise

One of the critiques of the study was that it didn’t do much to understand post-exertional malaise, but Nath said the team is still working on its measuring of it in “multiple ways”. Indeed, one of the participants in the study reported that cognitive testing, blood tests, the Seahorse mitochondrial test, a functional MRI, and transcranial magnetic stimulation were before and after the maximal exercise test.

Expect much more on PEM to come out.

Big Picture

The grand hypothesis. (Image from the study)

At the end of the paper, the authors proposed that an infection leads to immune dysfunction and changes in the gut microflora, leading to impact the brain, leading to decreased production of catecholamines (norepinephrine, dopamine, serotonin), which disrupts autonomic nervous system functioning and impacts the ability to exercise. A wonky hypothalamus results in decreased activation of the temporoparietal junction when people with ME/CFS try to move. That results in reduced engagement of the motor system, problems with movement and ultimately, exertion.

Data Sharing

Nath’s team reported that they “bent over backwards” to make sure that the study data is available in a new database developed by NINDS. Because it’s CCBY4.0 available through Creative Commons, anyone can use it. It can be shared, copied, made use of by companies, built upon, etc. They didn’t do much with sleep microarchitecture or circadian rhythms, but that data is all there waiting to be mined. Nancy Klimas has expressed great interest at merging all that data with her present data into the supercomputer. (The more data, the better the computer likes it.)

Ongoing Studies

The intramural study findings have prompted a bevy of further studies. A Veterans Administration / intramural NIH study on ME/CFS has begun. The team doing the modelling work on immune signaling is using a “drug targets selection process” to look for potential drugs that could return the immune system to normal. The exciting low brain norepinephrine finding is being explored further. Further gut studies that aim to understand the cause of the gut issues are underway. Hwang is following up on his WASF3 finding. Comparisons between the ME/CFS study findings and Nath’s long-COVID study will be made.

The Participants

Many people have proposed that the fact that no increased incidence of postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) was found in the people with ME/CFS meant that the group was healthier and not representative of the ME/CFS patient population, or perhaps didn’t even have ME/CFS. The study requirements – two weeklong stays at the NIH hospital – did indeed seem to call for a healthier study, but reports from the study participants indicated that many severely ill people did participate.

It should be noted that all the patients in the study went through extensive screening which included being assessed by a group of ME/CFS experts, and the ME/CFS experts had to unanimously agree that the participant had ME/CFS. In short, they were easily the most well-defined and heavily scrutinized patients to engage in any ME/CFS study.

Increased heart rates upon standing were commonly found in the ME/CFS group, but they were also found in similar levels in the healthy participant group. This may seem strange, but just as people can be hypermobile and be perfectly healthy, people can meet the biological criteria for POTS (increased heart rates) without being ill. (Increased heart rates, by themselves, are clearly not the core problem in POTS).

Participant Stories

Sanna said it was difficult to process the criticism the study received.

The courage and the determination that participants showed to move the science forward for their illness was nothing short of incredible.

In a video, Sanna related that she’d become ill in 2014 and by 2018 was essentially bedbound. She used her wheelchair and cane to get around during the study but was so crashed after one test that she had to be carried on a stretcher, needed a bedpan, and at one point was too weak to raise her hand and was unable to participate in the CPET exercise test or metabolic chamber. Stating that the study was “very tough”, she still said it was absolutely worth it and lauded Brian Walitt, in particular, and the team for care and attention they gave her.

Another person called participating in the study one of the most difficult she had ever had to make, but she was determined to contribute. Despite being an active person who regularly worked 60-80 hours a week, after coming down with ME/CFS, at one point she was unable to walk, shower or speak above a low whisper.

This participant was unable to be upright for more than 15 minutes without suffering severe symptoms. She praised the staff for their support.

At the time of the study she was unable to be upright for more than 15 minutes without suffering severe symptoms. Referencing Brian Walitt several times she said she’d never experienced “such devoted care” as she did in the study. Everyone, she said, “was so very careful”. It took her 8 months to return to her prior level of functioning but she said “ME/CFS patients need answers” and that she was “grateful to have participated”.

David Remer, a former doctor, enjoyed challenging himself with outdoor activities, wilderness canoeing and running before he came down with a virus. On a functional scale, David dipped to a low of 15 out of 100 in the year after the study.

His healthy sister, Susan, also participated in the study but then came down with long COVID herself after catching the virus (!). She participated in the Nath long-COVID study that’s underway – giving them a great before and after picture. She called the opportunity the study gave her to contribute a “blessing” and thanked Nath, Walitt and the staff for their “compassion and sound guidance”. (By the time this is all done, she’ll have spent about a month in the intramural hospital getting tested!)

Health Rising reported on the experiences of two ME/CFS participants in the study: Robert and Brian Vastag. Another former doctor, Robert reported that on a functional scale of 1-10 he was a 2, and that the occupational therapist on the study registered shock at how few activities he was able to still do. She had apparently never seen that before.

Brian Vastag’s severe ME/CFS problems are well known but he also referred to other patients in the study who were sicker than he was, and who said they “were absolutely annihilated by it” and took months to recover.

Panel Impressions

Next, it was over to a panel who gave their impressions of the findings.

Dr. Komaroff – noted that the most intensive study of ME/CFS ever done had confirmed many past abnormalities and uncovered some new ones. It suggested that “ME/CFS is a brain disease” induced by exhaustion which may result from deficiency of norepinephrine in one part of the brain. The immune exhaustion found, he predicted, will provide targets for potential treatments.

Ian Lipkin emphasized how critical it is to subset patients (gender/duration) and believed it was time for clinical trials.

Ian Lipkin – seemed quite taken by the B-cell immune exhaustion findings and spent some time asking, if an infection is driving them, how to find it. (Previous efforts have failed). He also noted that the turned-on innate immune defense system could be whacking the mitochondria, and asserted that the time has come for clinical trials of drugs to inhibit the innate immune system as well as trials to improve gut butyrate levels.

At the end, though – noting the need for effective advocacy when it comes to the NIH – Lipkin said, “if I learned anything at 40 years of doing this work, we need better advocates”. (I would say we need more advocates (I was the only one in the 5 staff meetings in the recent advocacy week), and we especially need more money for advocacy.)

Vicky Whittemore (NINDS) – highlighted the need to subset patients according to gender and duration and to stop throwing everyone into the same basket, citing the Roadmap report in the need to move as quickly as possible to clinical trials.

Joe Breen (NAIAD) – citing one study participant’s desire that her grandkids wouldn’t have to experience what she has – said, “I hope we don’t have to wait that long”, and noted the suffering that many have and continue to undergo. He highlighted the immune exhaustion and brain imaging findings.

Dr. Klimas said studies like this help get ME/CFS to clinical trials and called for them to start as well.

Dr. Klimas – was not disturbed by the small numbers. She called the study “very special” and talked of how excited she is to get all that data into her computer modelling work to help understand and find treatments for ME/CFS. Her computers, she said, are “never cowed by more data”. Dr. Klimas has been chomping at the bit for clinical trials for years and she said, “Let’s get to clinical trials”, and those clinical trials should be quite long.

She said her group is modeling ME/CFS patients as a whole, breaking them into gender subsets, and modeling each person as well and this “highly granular data” will help them to do that.

Avindra Nath (NINDS) – Then it was back to Dr. Nath to give his final thoughts. It was Avindra Nath who most explicitly laid out the case for clinical trials. You can study the physiology forever, he said, but if you keep waiting for “the answer”, you’ll never get to clinical trials.

Nath said the study identified “multiple targets for intervention” (i.e. multiple possibilities for clinical trials), and asserted that “combination therapies” will be required. He highlighted immune exhaustion and check point inhibitors, B-cell and T-cell activators, and non-specific immune modulators.

These should be done using platform studies, where a number of drugs are tested against one placebo-controlled group. Crossover studies where patients are put on one drug, then another, then placebo, etc. can help as well.

He said there’s light at the end of the tunnel and that if we all work together, we’ll find cures for this disease.

Conclusion

The study – which involved 75 researchers – validated past pieces of the puzzle and added new ones. It was a success.

Despite all the angst and controversy the study findings first aroused, this study was clearly a significant success for the ME/CFS community. Despite its reduced size, it achieved its goal of providing numerous openings for future research, and the small size may have produced a silver lining: it suggested that when done correctly, ME/CFS is very amenable to study even when small sample sizes are present.

Past findings were validated (B and T-cell abnormalities, T-cell exhaustion, brainstem abnormalities, mitochondrial issues, low HRV, low gut butyrate, low gut diversity, lipid abnormalities, reduced energy output, reduced dopamine, gender effects) and promising ones popped up (temporal parietal junction functioning linked with poor motor performance, reduced CSF norepinephrine and butyrate levels). The reduced CSF norepinephrine findings appear to present a particularly enticing finding as the low norepinephrine production in a potentially critical area in ME/CFS – the brainstem – could affect not only the effort/reward/movement issues found but also brain energy levels.

The effects that assessing gender on the results of the molecular biology or “omics” were nothing short of remarkable. Increasing study size is often a key to achieving statistical significance, but in this case, decreasing the sample size by dividing the study by gender dramatically improved the omics studies results. Even the researchers seemed startled by the large separations between healthy controls and ME/CFS patients that showed up once gender was taken into account. These findings suggest that simply separating the genders in future studies (or by reassessing past study results by taking into account gender) could be very helpful indeed.

The study has already spawned at least 8 follow-on efforts, and Nath – a senior NIH official – has proposed that a variety of clinical trials take place.

- Watch the Symposium here.

Thank you for the article Cort.

I just want to note that while, yes, this paper has received a much larger amount of criticisms than the authors anticipated, that does not mean that we should stay away from pointing out major flaws.

The fact is that the disease mechanism hypothesis was extrapolated from the data on shaky foundations. Now this doesn’t undermine said data, which will be very useful. However, the mechanism hypothesis completely discounts PEM, and it is very easy for clinicians to read the abstract and think that patients brains are fooled into PEM and no real damage is being done.

Professor Tod Davenport went as far as to call for a retraction due to these issues, especially the fact “effort preference” was based on a test contraindicated for physical illness (meant for anhedonia in depression). Professor Wurst, who has studied biomedical findings in PEM, stated in reaction to the study that “The pathology of reduced exercise capacity is different from PEM”.

Now I can still point this out while being thankful to dr Nath for his work. But I think it is important that researchers hear this criticism and are open to it, not dismissive.

Thanks. For me, I can see how hypothesis might be able to explain PEM. (The study did little on PEM but that work is apparently continuing) The brain says no to further effort – but then we all have to live and survive so we engage in further effort – so what does the brain when it thinks we’re going too far? It punishes us to stop us from doing that.

Just as the brain whacks us with the symptoms of “sickness behavior” when we get a cold – so that we don’t exert ourselves, it whacks us with PEM to stop us from moving and exerting ourselves when, from its vantage point, the cost is too great. (That’s my laymen’s take on it!)

I hadn’t seen Todd’s request for a retraction but the fact that he asked for such a severe action suggests to me that he’s not aligned with the hypothesis presented. The hypothesis presented seems pretty mild at least to me (a brain-based lockdown of exertion) something that might elicit more a difference of opinion than a retraction – so I assume he thinks the study has more dire implications than that or that I’m missing some of the implications of the hypothesis presented – which, of course, is entirely possible 🙂

Thanks for the answer! Yes, I am quite hopeful for the studies yet to be done, and thank you for bringing my attention to it as I wasn’t aware, before reading your very comprehensive (as always) article.

While I do note that there is a possibility of explained PEM, through that sickness behaviour, I don’t understand how this would explaining the permanent worsening of baseline and the fact someone (like me) can be so severe they haven’t been able to speak a word in months. Or the fact that Wurst and others studies have shown clear biological damage in the PEM state.

Anyways, I’m very much looking forward to seeing what the PEM findings are. 🙂

I hope that they really focus their funding and efforts on PEM, as it intuitively feels as if it is what is underlying the disease.

It is indeed a mystery how people get soooo ill. This kind of debility is REALLY unusual. Remember the part in the blog where the occupational therapist was shocked at how few activities the former doctor could do? I was told that kind of functional loss is not usually seen until we get very old.

I have to think the brain must be very heavily involved to get to that state. I’ll bet that at some point something is going to show up that is so off the charts abnormal that everyone gasps. We just haven’t found it yet.

Still, simply separating the genders made a huge difference. Maybe that’s one thing that will help us get there.

First of all TY both so grateful to you as always Cort for your diligence and Yann I def echo you too that… PEM is the pathognomonic symptom of the disease so … its weird to have it be any kind of afterthought? And patients’ bodies still spoke volumes!!?

Background: I’ve had ME for 20 years now and have been “mildly severe” (bedbound 21-23 hours a day but h generally able to sit up…) since Dec 2021. Esp as this violently reduced activity has actually freed me from PEM? I think I may have a more physical preload failure+muscle (cerebral venous/spinal?) subtype even tho I’m cognitively disabled AF I don’t think cognitive exertion is a PEM *trigger* for me the way it is for many/most PwME? My brain never shuts off lol and that seems to have 0 bearing on PEM. I can now witjout midodrine/mestinon even move my arm reslly without violent blowback/a “cardiac pulling” sensation that is alarming.

Firstly the metabolomic data—t including some you documented beautifully above from this study!—seem strangely missing from the Grand Hypothesis diagram. isn’t that (what my friends affectionately call The Poison Theory) the most obvious missing link that explains both temporary bouts of PEM AND permanent/longer term relapses / progressive disease (be it gradual or sudden)? I see “reduced CNS metabolites” in that disgrsm which also seems nasty lol and like it could be a feedback loop?! but if every exertion —every signaling between say your muscsrinic or acetylcholinergic receptors or every time your brain tries to Do a Thing / move a limb / write an email it triggers a nastier “dosing of poison?!”

Well that better explains both 1) cognitive impairment (esp the more peculiarly profound kind msnh pts get which should not be overlooked here) 2) progression.

And what if the brain problems at least in part are ~actual brain DAMAGe~ as we see on 7T/dynamic/fancier newer MRI? And as Jarred Younger seems to be seeing (with eg the leukocyte infiltrations he thinks might show up in his latest edgiest imaging project)?

What if the poisons (let alone w accompanying structural vascular spinal problems!) damage our brainstems? our cortices (including that motor cortex)? muscle tissue? our autonomic nerves? And/or our receptor function?

And the damage can often/usually be cumulative? /reach different stages for diff patients based on which brain regions, brainSTEm regions, and/or neurologic “channels” /circuits get ravaged by which poisons ? (ME has been described as a “chsnnelopathy” I recently discovered! Which really resonated w me for how it can be sooo debilitsting w no apparent tissue damage although IdT we’ve studied muscles or brain well enough at all!).

Also interesting to omit is that incredible “brainstem thermostat”—a new brain organ!!—just discovered a few weeks ago! (Caudate nucleus …?) Which to me should be on this diagram on the left most side or as another “bridge” in the entire feedback loop. To me this strikingly explains Ron Davis’ hypotheses re innate immunity getting SO tweaked (most often but not exclusively by) infection (and childbirth/vaccines/surgery/injury etc) and also ties together some of these observations.

ROSs… peroxides… ammonia … glutamate … lipases I reckon… Al kinds of shit that shouldn’t be in our bodies or shouldn’t be in it in high amounts is just basically poisoning us. I liken movement for myself now as being akin to a receiving a slow but also sporadically bursting push of atropine or cyanide … thst messed w my autonomic function and turns my muscles to acid and my brain to a horridly alarmed/asphyxiated state. (Oh we left out blood gas issues!)

Basically there’s something in this Grand Hypothesis that forms a heinous ~positive feedback loop~ and I think they should’ve made the visual of that far more obvious. And that they omitted a bunch of well supported putative mechanism of this.

Like you I was surprised that it was not a central focus but we’ll see what comes out of it. You’re right the metabolomic stuff didn’t figure in the grand hypothesis much although the mitochondrial problems could have been tucked in there. It was not given as much emphasis as the other parts of the study.

Intuitively, it seems to me that a lot of junk is present -certainly in the brain but probably elsewhere that should be washed out. Then there are the possible autophagy problems as well – another instance of that.

I could have written this, I’ve got the exact same thoughts re: ron davis’ hypothesis and ammonia. It makes perfect sense to me the brain would try and limit effort if effort literally poisons you.

What was found to be the differences between genders? It’s mentioned that they are significant or even “wonderfully significant “. But never explained what the major differences are?

I’ve been wondering since forever how the “dominos” of this illness are set up. The order of things is still foggy to me. (Infection THEN immune system/gut THEN brain.) So it suggests BOTH the immune system domino AND the gut domino get pushed over by the same infection, and then BOTH of those push over the brain domino?

And what falls under the term “infection”? Bacteria, virus, mold, toxins? Is the study leaving any of them out?

Once again some heavy lifting, Cort. Thanks.

I like your analogy of dominos! Tho I think the disease can “cycle” or “idol” for a while when we’re in plateau mode where no new domino is knocked it’s just a shitty / less than healthy cycling at status quo w usual (for that person) PEM/ thresholds + consequences ? And then progress when certain new dominos are knocked down (whether a day later or 18 years later)?

It’s completely understandable that ME patients are, in general, cautious about lending our trust to research and its researchers. We have learned the hard way that it’s necessary.

However, I have a heartfelt response to Nath’s comments on the more extreme or knee-jerk criticism – especially when researchers are genuinely working so hard on our behalf (and *not* with the disdain or ulterior motives that we’ve seen from some). I sure don’t want them to stop their research and I hope they will continue – and have an understanding as well of what we’ve been subjected to as good reason for our caution.

That said, I truly feel the omission of a 2-day CPET – the gold standard test for assessing functionality – was a major missed opportunity. Perhaps the cohort makeup (and a big thank you to those who took part – it must have been incredibly hard!) and the pandemic cutting the numbers down was the reason…? I really hope they rectify this by including it in future studies – in my view, it’s crucial they do so.

It was hard to hear Nath say that! He has been so forthcoming and helpful. I sincerely hope he does not take anything negative said to heart but understands it comes from a patient population that has undergone a kind of gaslighting that virtually no others have.

I think we, as a community, need to really hear what Nath said. We have legitimate and long standing reason to be cautious, defensive, resentful, frustrated and more. While it is understandable, it is NOT helpful and it is not serving us well. The research tides have turned and it is incumbent upon us to turn with them if we want intelligent, skilled, compassionate and interested researchers to work with us.

If we continue to treat them as enemies, we will not get where we want to go. It is time to take a partnership approach with researchers to bring more of them into the fold, not repel them away. Of course Nath would take the negativity to heart. Why wouldn’t he given the way we, as a community, handled the report.

Yes, the researchers could have done a better job explaining that effort preference refers to a biological process, not a psychological one. We could also have done a better job of asking first rather than attacking first. If we want better, we need to do better.

Time to look in the mirror and ask ourselves what we need to do to work with those who are trying to help us instead of working against them. If you were the researcher, would you want to work with us when the best we can offer is criticism instead of reasoned support? I wouldn’t. Of course we need to let researchers know when they have it wrong. It is equally important we do that in a way that is encouraging, not discouraging. It is time for us to come to the table prepared to cooperate not alienate. And we need to hold ourselves and each other to account when we don’t.

Nicely said. It behooves us not to slip into this us vs them mindset. I emailed Nath to thank him for all his work and he emailed back, I hope he doesn’t mind my making this public: “Our job has just begun. We will not rest until we find treatments and cures for this illness…and that “I remain strongly committed to help alleviate their pain and suffering.”

🙂

This gives me a lot of hope. Much respect to Dr Nash for the way he responded to the misunderstanding.

Agreed! I am so glad he’s sticking with us! 🙂

I disagree that the patient community incorrectly/over-responded to use of the term “effort preference”. I would be ok for that language to be used deep within the report where only experts might see it, but it’s in the one page summary (which is the only thing we can expect health practitioners and individuals might read). Since the public, employers, and disability insurance don’t have a test for mecfs to point to, anything that could make this disease appear in part a choice is devastating to us. I ask Nath to please not get frustrated and I thank him with my whole heart for helping us get to the bottom of this illness.

I agree it would have been better for everyone if some other words had been used but I didn’t really say that the ME/CFS community had over-responded. To be sure I felt and do feel that some people reacted without trying to understand what the term meant but I also wrote that the backlash was inevitable “Still, on the ME/CFS side, the words “effort preference” were bound to raise hackles – there was just no way that was not going to happen in a patient population that has been fighting against being psychologized for decades. It’s unfortunate that the NIH couldn’t somehow find a way to get the word out ahead of the paper.”

Nath seems to be fine thankfully 🙂

Cort, Is it you or is it the NIH that is using the acronym “POTS” incorrectly. Healthy controls with no complaints do not have POTS. They may have postural orthostatic tachycardia on a stand test or tilt table test and have a change of greater than 30 beats in 10 minutes. But that is not POTS or Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Sndrome. To be POTS there also has to be 6 months of symptoms and an intollerance in the standing or upright position. In other words there has to be a complaint of symptoms that are intolerable in uproght position that are relieved by change of position back to supine. That is why they ask the patients about their symptoms during stannding in everyday life and during any test and the duration of those symptoms.

I think the term, “effort preference of the brain” more accurately depics this as a brain function, rather than a problem with motivation.

The inability or lack of effort to incorporate a working understanding of PEM is a major failure IMO. As it is the central element of this illness.

I’m afraid this statement is incorrect: “It’s possible to have POTS and be completely healthy”.

In order to be diagnosed with POTS:

“All of the following criteria must be met:

* Sustained heart rate increase of ≥ 30 beats/min (or ≥ 40 beats/min if patient is aged 12–19 yr) within 10 minutes of upright posture.

*Absence of significant orthostatic hypotension (magnitude of blood pressure drop ≥ 20/10 mm Hg).

* Very frequent symptoms of orthostatic intolerance that are worse while upright, with rapid improvement upon return to a supine position. Symptoms … often include lightheadedness, palpitations, tremulousness, generalized weakness, blurred vision and fatigue.

*Symptom duration ≥ 3 months.

* Absence of other conditions that could explain sinus tachycardia

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8920526/

The researcher should have said: “It’s possible to have postural tachycardia that meets the diagnostic criterion for POTS but not have POTS itself because you don’t meet the other diagnostic criteria”.

I am afraid that many medical people are still not clear on the terminology of orthostatic intolerance. Yikes.

So you can have postural tachycardia and suffer no ill effects from it, but you can’t have POTS and be healthy, because POTS by definition involves feeling unwell and being unable to carry out normal daily activities.

Postural tachycardia is not a disease; POTS is.

Fine – yes, I think most people understood what I was trying to say but you are correct. Perhaps the researcher said exactly that and I phrased it incorrectly.

Your comment does bring up one other thing, though. No more ME/CFS patients in the trial had increased symptoms upon standing and increased heart rates than the healthy controls. It was the lack of symptom exacerbation that was really surprising. The study said there was no difference in “tilt-related symptoms requiring test cessation” – which suggests that they didn’t assess more minor symptoms.

I hope it was your interpretation Cort about POTS. It is not surprising that they do not find POTS in ME/CFS patients in their study. The number of patients n=17? are too small for that. For that reason alone, researchers cannot make any meaningful statements about this.

In larger groups you do see POTS in ME/CFS patients. Most studies find between 5 and 30% ME/CFS patients with POTS. And as far as the brain concerned, almost all ME/CFS patients have severely reduced blood flow. That was not measured in this study.

A double exercise test is a requirement to create the best possible select group. The healthy group with an increased heart rate can be explained, among other things, by a reduced fitness level. They also have to do an exercise test to make a good comparison.

Certain statements by scientists are embarrassing.

That said, I think the brainstem disruption and stress hormones are positive findings to explain this condition.

Cort, I’m sorry I sounded a bit harsh, I didn’t mean to.

Wasn’t there a study a while ago in which a lot of people with ME/CFS turned out to have low blood flow to the brain even though they didn’t report orthostatic intolerance symptoms? I think it was one of the Visser, Rowe, et al studies.

(Forgive me, but I can’t recall whether the study under discussion here measured cerebral blood flow. Is this the one where they did a special MRI to measure it? I thought they did find differences in that one.)

Here is the study I was thinking of:

“[W]e would caution that clinical symptoms alone may be insufficient to diagnose orthostatic intolerance, as some individuals who did not endorse orthostatic symptoms before the study nonetheless had substantial reductions in cerebral blood flow. This is evident from Fig. 3 in which patients, denying orthostatic intolerance symptoms in daily life, still had a mean cerebral blood flow reduction of 12% (reduction range between 1 and 46%).”

Basically, some people with ME/CFS did not think that they had orthostatic intolerance symptoms when questioned, but when they were tested their cerebral blood flow fell abnormally.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7044650/

This is a little bit surprising, but then remember that some people with orthostatic hypotension do not feel symptoms and fall or faint without warning. (I believe that is the situation that inspired Daniel Lee to create his Stat Health cerebral blood flow monitor.)

No worries. They did not unfortunately. The test Visser used – some sort of doppler device if I remember correctly – is not very common. I think his findings are fundamentally important.

https://www.healthrising.org/blog/2021/12/26/brain-blood-flows-long-covid-me-cfs-pots/

How should we view programs like DNRS, ANS Rewire and Gupta in light of these findings. It seems far more complex than just neuroplasticity exercises and meditation. I can see how those can help us feel better within our CFS envelope but I don’t see how a true recovery from true CFS could come if our bodies are this deeply dysfunctional

:). Some people do get better and some people get well and a lot of us have tried those programs and either not recovered or have not improved much – so there’s that. I wonder, though, if this “reward” thing might be connected. We’re going to get into “reward” more.

I’ll take this moment to comment that ‘reward’ seems overplayed per your summary. Reward is associated with dopamine. But we’re learning dopamine does more than reward[1]. And, of course, the study found strongest effects for norepinephrine.

To be a bit glib: reward seems especially rewarding to neuroscientists! Many experiments w/ animals have needed to involve rewards to get the animal to do the behavior/task that’s being studied. This has led to some systemic over-focus in my view. Fortunately, there’s a trend towards paradigms for studying more natural, less artificial behaviors.

[1] https://news.northwestern.edu/stories/2023/08/dopamine-controls-movement-not-just-rewards/

Thank you for this SALIENT af point!

It’s just such a frustrating and vulnerable place to be when you’ve tried for years to do these programs with little success but you’re so desperate to get better you feel like a failure if you stop. It’s a relief to hear there is such deep dysfunction going on, even though it’s bittersweet

I Cort,

I would put it this way. I guess there are many various causes (infections and viruses of all kinds but also personal psychological hypersensitivity to life stress factors, bad life habits or attitudes) that can affect the sympathetic/parasympathetic nervous system via the brainstem (with the new found switch as per one of your last articles) which in turn will affect the hypothalamus and disturb the entire body/brain system out of homeostasis.

If the cause of someone’s health problem (ME/CFS, FM, LC, LYME) comes from an infection or a virus, I do not really see how brain retraining could do much for this person. However, if this is something more personal, then I guess this could help.

Of course, there is no magic split line and some people will be helped while some people will not be helped, no matter the origin of their health problem.

Yes, it is hard to see how brain retraining does what it does and I imagine it does have to do with the stress response. I’m wary of the idea that people with psychological hypersensitivities to stress are those that recover from retraining or that viral infections do not play a role in their illness. It’s possible but who knows? EBV, after all, is virus which reactivates under the stressful conditions. I doubt that we’ll ever get the studies that are able to tell us what’s happening with brain retraining.

Something we know for sure is that mindfulness meditation (very close to brain retraining process I guess) does change the brain structure and behavior (proof from MRI done at least on Dalai Lama and Mathieu Ricard, if i am not mistaken). Their brain structure and behavior (size of the zone and intensity which highlights during meditation) is bigger and more activated respectively than non-meditating people.

Of course, if EBV is reactivated by stress and you retrain your brain maybe you can maintain it in check more easily. Who knows ?

Yes, excactly. I am doing a very good recovery and my main tool is mindfulness meditation. I think in sum, I spent about four months on silent retreat since I fell moderately ill (and had to stop working).

Indeed, it is a kind of retraining the mind(!) (in Buddhist psychology we don’t think that the mind equals the brain). The well trained mind has better strategies to protect us from stress and less stress means less ME/CFS reinflammation episodes. I am with those who think that ME/CFS is caused by herpes reactivation. But I think it’s not EBV but Cliff and Prusty with their research on HHV-6b have the most convincing data so far.

R. Nash I think is not on the right track. Just because a researcher is motivated, open-minded and friendly doesn’t mean he has anything valuable to add to the field.

The biggest problem with this kind of neurology that Nath is mainly invested in is that it is not a fact based science. It has the same quality that “neuroscientific” psychiatric research has. In fifty (!!!) years they haven’t found out anything about how to explain behavioural problems neurologically. I think it wouldn’t be a loss to not have this kind of researchers going into ME/CFS.

More and more researchers and opinion leaders are now understanding that herpes reactivation is the key question that has to be solved. Therefore I am not afraid that Nash and the NIH are able to derail a lot of money into fruitless projects.

Hi Lina,

Thank you very much for confirming to me what I new and thought for a while already. I just bought the book ”A Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction Workbook: 2nd Edition” from Bob Stahl and Elisha Goldstein. I am reading it eagerly and I know it will help a lot.

Personally, I have tested negative many times to EBV (mononucleosis) and I have never ever had any of the well known physical symptoms associated to Human Herpesvirus – 6. Various tests for sexually transmitted diseases with every new girfriend for caution were also always negative.

My ME/CFS started slowly (over a couple of months) during my bachelor degree 35 years ago and not overnight after a flu or any severe disease.

I did my homework and, in my case, I am pretty convinced that it is related to a very high stress level during childhood that got worse with badly handled life stress factors (scientific graduated studies, work in a state-of-the-art technology field, etc.)

Let’s see…

Good luck with it. Adverse early childhood experiences (ACE’s) have been shown to increase the risk of many diseases…

Thanks you very much Cort !

We know from recent research that exercises like that influence the autonomic nervous system towards settling down into a more normal state and also help the immune system to normalise via the vagus nerve (I think that was an article published on here recently?). It may be that if your body is close enough to a recovery tipping point anyway, it takes enough additional load off to let things improve in a virtuous spiral. That’s what it feels like, anyway

Which program are you doing and for how long?

I’m not doing a paid program, I’m doing my own thing with similar exercises. Only a few months so far but its looking more promising than anything since 2010 has at the moment, including with my objective tracking measures as well as just with how I feel

It is primarily meditation, mindfulness, positive visualization and pattern interruption?

No, I don’t do most of those at all except mindfulness (and some guided visualisations for helping my sleep). I find that for me, somatic tracking, humming, singing, breathwork, using the Beurer ReleaZer device, self-soothing touch, and autogenic training have been more useful.

But the point is not so much that there are magic things that have to be done, I don’t think, the point is to find which things work for you. For some people it probably IS the things you listed – but the process of trying things and learning to listen to your body and figure out what works for you is an important part too, I think. And what is working may well change over time, which is why the listening to your body is important

Really intrigued to hear that you’re finding this useful (and rooting for you!).

I’m curious to know more too, if you’d be up for sharing.

I was wondering if you were doing something like Stanley Rosenberg’s ‘basic exercise’? Or maybe taking a different approach that I haven’t heard of.

See what I wrote to Josh just above – I don’t think there’s ever going to be a single exercise or a single approach that helps everybody. I do a whole lot of somatic (body-focussed) stuff. I haven’t heard of the “basic exercise” you listed but the general idea of doing as much stuff as you can that’s aimed at down-regulating the nervous system, feeding back safety messages to your unconscious brain, telling it that it doesn’t have to be on high alert looking for danger.

There’s also a new book out by Mann & Rabin called “The Secret Language of the Body”. I haven’t finished reading it yet, but from the part I’ve read it has a lot of the same stuff in it if you’re interested. Ignore the part where it talks about “cure” if it’s triggery for you, I figure even if it gets me 10% better I’m still ahead of the game.

I found the Facebook group called “CFS/Long Covid/Post Viral Program & Recovery Discussion” helpful for info too, if you do Facebook stuff

Thanks, I really appreciate your reply. Yes, I think you’re right that this stuff is individual. A couple of the things you mentioned are ones I don’t know about, so I’ll do some exploring!

Here’s a link to a video about Stanley Rosenberg’s basic exercise if you (or anyone else) is interested: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rbowIy6kONY

Sukie Baxter has some YouTube demonstration videos of Rosenberg’s other exercises too.

Thank you for this summary Cort. Their messaging (& thus your summary!) is starting to get more sensible to me.

There’s still a bit of cognitive dissonance, with Mark Hallet sensibly mentioning origins in the brainstem & hypothalamus (the lower & upper extremities of the ‘ventral brain’), but then a lot of overinterpretation (imo) re motor pathways arising from top-down (the ‘dorsal brain’).

Wrt autonomic dysfunction, a notable finding I recall from the manuscript was the sympathetic underdrive evident in the abnormal Valsalva maneuver BP response. I think that, like Parkinson’s, regimes of orthostatic hypotension may be more prevalent in the ME population. Many forms of POTS may be comparatively more benign than ME (though I would hesitate to call it ‘normal’).

These initial reactions aside, this sure seems like it was a worthwhile & potentially fruitful symposium. Thank you again.

I don’t understand the motor cortex issue at all. There are possible problems with motor control but the motor cortex is being engaged and operating normally? If its still feeding messages to the muscle what is the problem? Is the brain feeding us signals (fatigue, pain, etc.) not to move or exert ourselves? Is that it? It all seems a bit mysterious. 🙂

Cort, to me it sounds almost like the brain is “yelling” at the muscles and they either are not receiving or correctly interpreting or responding to the central message. Since pyridostigmine, a ACh reuptake inhibitor active at neuromuscular junction and therefore indicated in MG, is so often helpful to ME/CFS patients, that seems to me like it might fit.

(…)”regimes of orthostatic hypotension may be more prevalent in the ME population”.

This assumption is not true, there is also hypertension and hypotension is excluded for a POTS diagnose.

As for movement and muscle problems, this is ridiculous compared to Parkinson’s disease and other neurological diseases. ME/CFS patients can move normally. There is nothing wrong with the motor control.

The reward system – dopamine – is certainly disrupted.

Primary or secondary POTS is certainly not benign or normal!!!

Is this statement from Cort? Or a scientist from the study?

I don’t think that’s in the blog. My guess is that what they’re saying with motor control is that the motor control part of the brain is having trouble assessing what’s going on and perhaps just shuts things down.

If the researcher said the same kind of evaluation problems are seen in Parkinson’s Diseases – then the same kind of evaluations are seen in Parkinson’s Disease. He’s the expert!

He didn’t say that neurons in the basal ganglia are destroyed in ME/cFS just as they are in Parkinson’s Disease because they’re not. Two diseases can share some characteristics while not being alike. That makes sense doesn’t it?

This most intriguing. I light up when I read about neurotransmitters and brain health. I won’t bore anyone with my story but thought I’d share a peculiar prescription medication that was recommended to me recently. A non-stimulant ADHD medication that targets the increase of norepinephrine (SNRI) and dopamine. Strattera. I have tachycardia or some form of POTS and I am very anxious about taking it. But what if?!

Strattera- that is really interesting. It looks like it increases norepinephrine levels in the brain (where they are low in ME/CFS) but not (I guess) in the periphery. The ADHD / ME/CFS / FM connection is so intriguing. A blog on stimulants is coming up but I may try to shoehorn strattera in there.

I look forward to your article. I’d be very interested in the research done so far on the outcome of taking adhd medication (or Strattera because it is different) and success stories if there are any. Again, what if?!

I was also intrigued by the norepinephrine finding because I use pseudoephedrine nasal anticongestant tablets as an occasional trick when I need to get up early. When I take it directly before sleeping, I am able to wake after 5.5 hrs of sleep feeling activated. Google says about pseudoephedrine: “Pseudoephedrine is a mixed-acting decongestant, which activates α- and β-adrenergic receptors directly by binding to the receptor itself, and indirectly by causing norepinephrine release in synaptic nerve terminals.” So I wonder if that could relate to the findings. It is not a magic bullet though because taking them too often would cause overstimulation and crashes, and pseudoephedrine also comes with a recent health warning https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/ema-confirms-measures-minimise-risk-serious-side-effects-medicines-containing-pseudoephedrine#:~:text=An%20EMA%20review%20has%20found,affecting%20the%20cerebral%20blood%20vessels.

Note that methylphenidate, a similar drug, is occasionally given for PoTS 🙂 I would definitely try to shoehorn Strattera in! Would be very interested.

Any thought in whether they will fast track clinical trials? We can’t wait 10 years for some help.

I don’t want to disrupt the party. It will take much longer – than 10 years- before proven effective medication is available for ME/CFS. Regarding the immune system that Nath wants to use medicines for. Don’t expect too much from that.

That’s just completely wrong – you bearer of bad tidings! It would take one clinical trial of an already available drug – which is what Nath is talking about – to open the door for its use in ME/CFS.

That’s why the RECOVER Initiative is testing Ivabradine, IVIG, Paxlovid, a stimulant, etc. If the results are positive doctors will immediately be willing to prescribe those drugs.

Who knows how long it will happen but it could happen pretty quickly.

As to the last point, let’s just assume for the heck of it that Nath knows a bit more about these drugs than Gijs. 🙂

Most drugs have been tested like IVIG, Ivabradine, immunomodulators by other experts (cardiologists, immunoligist…) isn’t a solution. Lets asume for the heck that Nath is not expert on these drugs either because he is an neurologist -:)

Even with available drugs you need objective endpoints before it will be given to patiënts Cort, it doesn’t workt that way you decribe in case of ME that can take a long time.

It is always 10 years -that also is an assumtion- i hear that kind of statements and read it written by bloggers for almost 30 years now. Don’t give false hope based on assumptions. It is a long road even if Nath find something…

Unfortunately I couldn’t correct the spelling mistakes anymore, -:)

As Maureen Hanson asserted in the Roadmap presentation we have enough endpoints to determine if patients are getting better – and we have clinical trials on LDN/mestinon, etanercept/mifepristone, rTMS and inspiratory breathing underway.

What we don’t have are the validated clinical endpoints that drug companies believe they need to bring new drugs to market. We have enough though to get other drugs. We’ve had trials on florinef, Vyvanse, Rituximab, and, of course, tons of trials on CBT/GET.

We just need the funding to move forward on many options.

I totally agree on this one, we need funding. The CBT researchers never had any problems with that didn’t they 🙂

What continues to amaze me is that authoritative experts such as Nath, Lipkin, Komaroff, Ron Davis and many others do not receive research funding.

It is scandalous that with the knowledge there is now about ME/CFS, there are still no good guidelines and acceptance in the medical world.

If doctors would just really recognize this terrible disease and treat patients as human beings, it would make a big difference.

Compassion doesn’t cost any money at all….

nice to read about a study but its like a fire , if you dont know the source, you dont know what can be good and what is realy bad (like wather on a oil fire).

I have Fibromyalgia and CFS , started after a meningitis if 1 was 3 years old, and it grows and grows , but I was born with hip problems so the symptoms of fm and cfs are long times covered (we sleep not so long in my family, so it covered the cfs for a very long time). But today I can say that my brain like to doo things but my body cant so if I do because it is importand it ends with big problems. Funny thing : I stay 14 – 22 hours in bed but my muscels look like every day jogging because the fibro let my muscles “work” till I become muscl spasm (without my dronabinol drops a lot of muscle cramps every day, and with a few a week. only the firbo have “its time” like the last 3 weeks , then I have pain in my joints and muscles as if someone had stepped on them. By the way I have the meningitis 1976, was born 1972 and the fond fm 2011 and cfs 2017. So if they realy know if some have one of this deasys then they can do really good study’s before its like a medical blind man’s buff game

I think it will be an intermediate of what you both are saying. You need more than one trial for wide-spread uptake by doctors of a drug, especially if it’s not a placebo controlled randomized trial set up well with validated endpoints (which not sure we actually do have in ME/CFS). Can there be evidence of efficacy? Yes. But it will not be registrational (i.e., not enough for the FDA to approve a med for ME/CFS specifically) so you are still in the situation of off-label use by SOME doctors who are convinced, but probably hit or miss insurance reimbursement and many doctors who won’t be convinced. So I think in the next 5 years we may see more data that may convince some doctors to prescribe other things off-label that might be useful.

My brain is exhausted but reading the Gist helped.