The second part of a 3-part series of blogs on the “Deep phenotyping of post-infectious myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome” study looks at who was in the study and how they were selected, how severely the study was truncated by the pandemic (quite severely), the big missed opportunity of the study, the many immune, metabolic and other findings, the exercise and deconditioning issue raised by the study and then finally, in the appendix it takes yet another look at the “effort preference” issue (for those who dare to go down that tunnel again :))

Participants

Questions have been raised regarding who was in the study, yet the participants were vetted by ME/CFS experts.

Not surprisingly given some of the results (no increases in small fiber neuropathy, orthostatic intolerance, cognitive and sleep problems), and the 4 people who recovered in the 4 years after the study (one reportedly because of a coronavirus infection (!)), some questions have been raised about the ME/CFS participants in the study. (Note, though, that this is a rare study that followed patients for a considerable amount of time afterwards.)

The study had in its favor a rigorous process vetted by ME/CFS experts to filter out people who did not have ME/CFS or any confounding factors. Some have argued that the criteria were so strict that they excluded some ME/CFS patients and that is surely true. The goal of the study, though, was to examine a certain slice of ME/CFS – people with a validated infection who had been ill for less than five years and had as few confounding factors as possible; i.e. the study was never intended to be representative of the ME/CFS population at large.

Most of the exclusionary factors were normal (other major diseases) but some were quite strict. For instance, the decision to exclude patients who were taking medications that could affect the immune system, the nervous system, or the metabolism may have removed many patients from consideration.

All 17 participants met the Institute of Medicine (IOM) criteria for ME/CFS created by an ME/CFS expert panel. Eighty-two percent met the Fukuda criteria and 53% met the Canadian Consensus criteria. After the first week-long study, all the participants were assessed by an ME/CFS panel of doctors (Lucinda Bateman, Andy Kogelnik, Anthony Komaroff, Benjamin Natelson, and Daniel Peterson) who unanimously agreed that they had ME/CFS and should be in the study.

The Pandemic Giveth and the Pandemic Taketh Away.

People with ME/CFS and other post-infectious diseases have the coronavirus pandemic to thank for the increased attention to their diseases, but the pandemic took from this study as well, and more than we knew.

The study was truncated even more dramatically than we thought. Of the 17 ME/CFS and 21 healthy controls in the study, only 8 ME/CFS and 9 healthy controls completed the second weekend of the study. This was significant because while the first week of the study was designed to weed people with ME/CFS out of the study, the second weekend – which included the exercise test among others – was designed more to address pathophysiology.

This (and probably other factors) led to quite small sample sizes in many tests including small fiber neuropathy (n= 11/9/; ME-CFS/HC), exercise testing (n=8/9; ME-CFS/HC); muscle fiber testing (n=12/11 – ME/CFS/HC), actigraphy (steps/activity; n=11/11 ME-CFS/HC), etc.

The study, then, turned out to be severely inhibited by the pandemic.

Missed Opportunity

A major aspect of ME/CFS – post exertional malaise – was hardly explored in this study.

The most surprising thing to me about the study was that the distinguishing symptom of ME/CFS – post-exertional malaise (PEM) – was virtually ignored. When I heard that the exercise stressor was going to be part of the study, I assumed they would measure everything they could before and after the exercise session and try to get at the heart of this exertion-challenged disorder. (Remember SEID? – the Systemic Exertion Intolerance Disease?)

This study, though, used a traditional approach to study an untraditional disease. Only three factors (dietary energy intake or total body energy use, sleeping energy use, respiratory quotient) and a couple of cognitive tests were assessed before and after the exercise stressor. All the other tests were apparently done at rest.

Findings

Even with all the provisos – the small and truncated study, the less-than-representative sample of patients, and the lack of interest in PEM – the study nevertheless provided many interesting and, I think, potentially helpful findings. I would argue the fact that despite its shortcomings, the study still managed to produce a considerable number of findings, indicates that ME/CFS is very amenable to study if it is studied correctly – and this study provided an important clue on how to do that.

Basic Stuff

Actigraphy – Only 11 people with ME/CFS and 11 healthy controls wore ActiGraph GT3X+ accelerometers to assess their activity levels. The activity assessment was important in the authors’ conclusion that the reduced maximum energy outputs found during the exercise test were at least partly the results of deconditioning. The study found that the healthy controls averaged 7,111 vs 3,618 steps per day of the ME/CFS patients. While no differences in sedentary, light movement, or vigorous activity were found, a very large difference in minutes of moderate physical activity was found (40.64 ± 37.4 versus 6.4 ± 7.0; p – 0.007).

Dysautonomia was common in the ME/CFS patients but not in the healthy controls. A nice, long 40-minute tilt test that assessed plasma epinephrine and norepinephrine levels did not find increased rates of POTS or altered levels of those neurotransmitters. It turns out that the problem was not a lack of orthostatic intolerance in ME/CFS. About half the ME/CFS patients exhibited significant drops in blood pressure and a third met the criteria for heart rate increases characteristic of POTS. The problem was that a smaller but still similar number of the healthy controls met those criteria as well.

While the sleep study results were reportedly not different in the ME/CFS patients, the supplemental results section stated “Sleep fragmentation was noted in 10 PI-ME/CFS participants (three mild, five moderate, two severe).

Immune System

The immune findings were given lots of attention in the press and agreed with two important prior findings in ME/CFS: immune activation and immune exhaustion are present. An increase in the percentage of naïve and a decrease in switched memory B-cells in the blood could suggest the body is trying to fight off an infection and/or has an immunodeficiency problem.

Increased levels of markers of T-cell activation, PD-1+ 723 CD8 T-cells in the cerebrospinal fluid are a marker of T-cell exhaustion and have been found in several neurodegenerative diseases such as multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s Disease (PD), and Alzheimer’s Disease (AD). Given a few findings suggesting that amyloid proteins may be present in ME/CFS, it’s interesting that these T-cells are believed to be removing these symptoms from the brain in PD and AD. Note, though, that Nath was relieved not to find any evidence of the overt structural changes in the brains of ME/CFS found in these very difficult-to-treat diseases. That should make ME/CFS more amenable to treatment.

Detailed autoantibody testing did not reveal any evidence of autoimmunity.

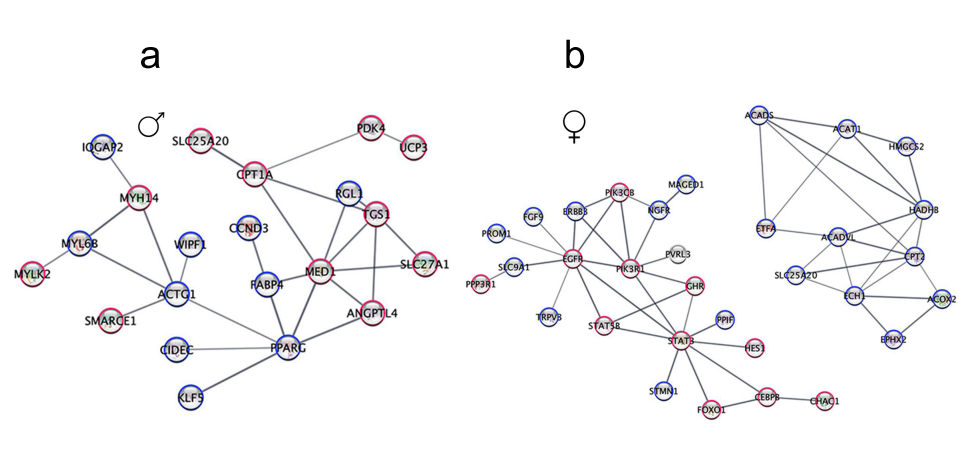

A big male/female split is going to be a major takeaway from this study. We’ve seen this before in Hanson’s studies and others, but seeing it displayed across such a wide area of factors in this study emphasized how important it is to separate out males and females in future studies. One wonders how much of the inconsistency in study results could be the result of this split not being taken into account.

A gene expression study of immune cells in the blood found that only about 2% of the immune genes that were distinctive in ME/CFS were shared by both men and women!

Check out the dramatically different immune networks found in men (a) and women (b) with ME/CFS.

Males showed alterations in T-cell activation, proteasome, and NF-kB pathways, while women showed alterations in an entirely different part of the immune system – B-cells and leukocyte proliferation processes.

Perhaps similarly to the muscle gene expression results (see below), both men and women exhibited problems with their T-cells – just in different ways. Men’s cytotoxic T-cells in their spinal fluid had increased CXCR5 expression, while women had more CD8+ naïve T-cells in their blood.

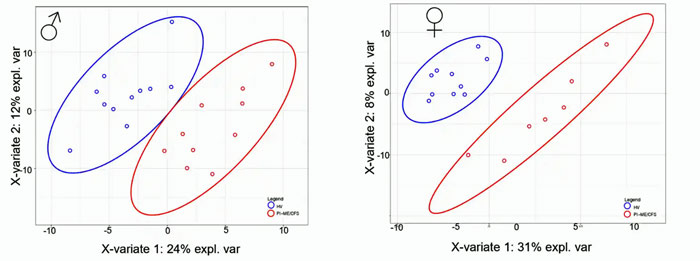

Notice the very nice separation the principal components analysis found between the ME/CFS males and healthy control males and the ME/CFS females and healthy control females. Even with the low sample numbers, the ME/CFS patients were easily differentiated from the healthy controls.

Even with a very small sample size, a principal components analysis finds a strikingly clear differentiation between male ME/CFS patients and healthy controls. (The same pattern was found with women).

The author proposed “persistent antigenic stimulation”; i.e. that a pathogen, or some other process, is constantly activating the immune system in both men and women. (Given its role in modulating the immune system, problems with the gut microbiome could also be contributing to this.)

Dr. Anthony Komaroff stated the immune findings were fully consistent with existing research and stated that the study provides compelling evidence that the immune system is chronically activated: “As if it’s engaged in a long war against a foreign microbe, a war it couldn’t completely win and therefore had to continue fighting.”

Despite the low sample sizes, the flow cytometry results found some striking differences between people with ME/CFS and the healthy controls.

Nath and his co-authors stated their findings suggest that something leftover from an infection — an antigen — continues to perturb the immune systems of ME/CFS patients. This “chronic antigenic stimulation” triggers a cascade of physiological events that eventually manifest as symptoms.

Cerebral Spinal Fluid

The cerebral spinal fluid findings had the potential to tell us something about what’s going on in the brain – and they delivered. Once again, despite the small sample sizes, look at the dramatic separation between patients and healthy controls that was achieved using cerebral spinal fluid metabolomics.

Once again, a very clear separation between ME/CFS patients (red) and healthy controls (blue) despite very low sample numbers. Men are on the left and women are on the right.

Dopamine

The ME/CFS group had reduced cerebrospinal levels of dopamine metabolites (DOPA, DOPA) as well as a serotonin precursor (DHPG) – two “feel good” brain chemicals. The authors called this evidence of “decreased central (brain) catecholamine biosynthesis” in PI-ME/CFS.

Dramatically altered levels of some cerebral spinal fluid metabolites were found.

Dopamine could almost be a “who’s who” concerning the neuropsychological issues that plague people with ME/CFS. If you’re lacking pleasure, don’t feel much “reward”, if you have trouble with movement or motivation, if you have trouble paying attention, being aroused (attentive – not the other), or having trouble with sleep, low levels of this brain chemical could play a role.

Dopamine abnormalities have quite a history in both ME/CFS and FM, with studies suggesting that dopamine is impaired in both. Dopamine is produced in the reward center of the brain – the basal ganglia – which has been implicated in both ME/CFS and fibromyalgia.

Andrew Miller found that inflammation reduces the levels of a cofactor called BH4 – which helps to produce tyrosine – the precursor to dopamine. Miller believes inflammation or oxidative stress may be whacking the BH4 co-enzyme in ME/CFS, thus reducing tyrosine and ultimately dopamine levels. Interestingly, Ron Davis is exploring the role BH4 plays in ME/CFS right now.

Miller believes that traditional methods of boosting dopamine by using amphetamines and dopamine reuptake inhibitors fail because dopamine production is being blocked by inflammation. Back in 2014, he proposed trying drugs like sapropterin (Kuvan – a synthetic form of BH4), supplements (folic acid, L-methylfolate, S-adenosyl-methionine (SAMe), and taking drugs to block inflammation such as etanercept (Enbrel). Drugs that can stimulate dopamine receptors (e.g. pramipexole, levodopa) would fall into the highly experimental category but might be helpful as well.

Several possible treatments that have popped up recently in ME/CFS and long COVID (Abilify, nicotine patch, amantadine) can impact dopamine levels.

A metabolomic analysis of the spinal fluid indicated altered levels of dopamine, tryptophan, and butyrate metabolites. Researchers have proposed for years that the tryptophan/kynurenine pathway may have gone awry in ME/CFS. While not much was made of the tryptophan issue, the researcher found that when they stripped out people in the study using SSRIs, the reduction in tryptophan metabolites was able to predict ME/CFS. The butyrate findings jive with the low gut butyrate levels and could tie in with the fatty acid issues found in prior studies.

The catecholamine hypothesis.

The fact that reduced norepinephrine levels – an autonomic nervous system neurotransmitter – were correlated with both “Time to Failure” and “effort preference” in the hand grip test, ME/CFS was intriguing as well given the role that the autonomic nervous system plays in motor activities.

The authors believe the CSF findings suggest that the HPA axis may help produce the low TPJ activity and ultimately the motor cortex findings.

Gene Expression of the Muscles

Concerning gene expression of the muscles, both men and women showed evidence of increased rates of oxidative stress – a potentially important finding as several studies suggest that oxidative stress is wreaking havoc on the muscle membranes in ME/CFS.

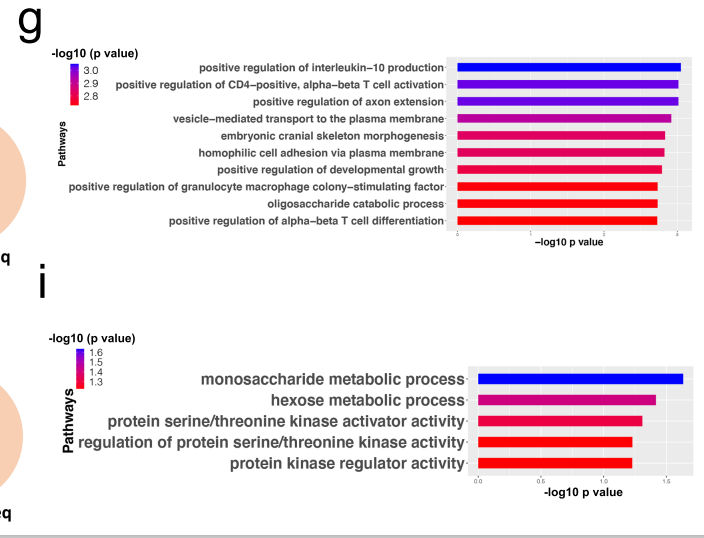

The pathways associated with the increased oxidative stress in men showed an upregulation of fatty acid beta-oxidation genes (genes associated with breaking down fatty acids to produce energy) and downregulation of TRAF and MAP-kinase-regulated genes. They also showed a downregulation of the hexose genes associated with glycolysis – where energy is produced anaerobically outside of the mitochondria – and a downregulation of mitochondrial genes.

Dramatically different gene pathways expressed in the muscles of men (bottom) and women (top) with ME/CFS indicating different issues were present. None of the major pathways were shared by both.

The pathways in the women, on the other hand, showed an opposite finding – a downregulation of fatty acid metabolism genes – plus a downregulation of mitochondrial processes in muscle.

Dramatically altered muscle gene expression networks in women (a) and men (b).

With fatty acid problems linked with different energy production issues in men and women (glycolysis – men; mitochondrial genes – women), this may be a case of all roads leading to Rome, with women and men taking slightly different ones to ME/CFS. Note again that these findings showed up despite low sample numbers (15 ME/CFS vs 9 HCs).

Lipids

Lipid abnormalities look like they may be becoming a big deal in ME/CFS and were assessed in this study but were downplayed in the results section that was titled “Lack of differences in lipidomics between PI-ME/CFS and healthy volunteers”.

While the univariate analysis of the 856 lipids (apparently lipid vs lipid) did not identify statistically significant differences between ME/CFS patients and the healthy controls, the multivariate analysis (which assessed relationships between lipids) suggested that lipids could be used to predict who had ME/CFS and who didn’t – a potentially major finding, one would think.

When the researchers compared the lipid profiles by sex, they again found substantial differences, with 50 lipids able to differentiate men with ME/CFS from male healthy controls but only 20 lipids able to do so with women. The authors noted they were similar to a prior ME/CFS study which suggested that the different lipid abnormalities in men and women could be promoting immune dysfunction and inflammation, and affecting the fatigue, chronic pain, and cognitive difficulties found.

The Gut

Rather simple analyses of the gut were done, and we’ve seen much more detailed ME/CFS studies, but differences were found as well. Both alpha and beta diversity were reduced and here again, we saw major differences in male and female ME/CFS patients. Alpha and beta diversity were reduced in men but not in women.

Dramatic differences were seen in the microbiomes of ME/CFS patients (red group) and healthy controls (blue group). (blue colors indicate less abundance; red colors indicate higher abundance)

The Elephant in the Room – the Male-Female Split

One thing this small but widespread study made clear – and which Nath emphasized in some interviews – when it gets down to these more detailed analyses – men and women differ in multiple ways in these diseases. Given the small sample sizes, it was rather remarkable that once men and women were separated, significant differences between them and healthy controls showed up consistently. One of the big takeaways from this study is that studying men and women separately could greatly quicken our understanding of ME/CFS.

Exercise Testing

Instead of the CPET test playing a major role in the study, it ended up playing quite a minor role. Even though less than half of the participants (8/9) ended up doing the exercise test, the study found that peak power, peak respiratory rate, peak heart rate, and peak VO2 (p = 0.004) were all significantly lower in the ME/CFS group. Plus, a lower heart rate reserve was found, and chronotropic incompetence was found in 5/8 ME/CFS patients. The fact that anaerobic threshold (AT) occurred at lower levels of oxygen consumption fit with the idea that the aerobic energy production system in ME/CFS is impaired.

The authors’ assertion that deconditioning is causing the cardiovascular abnormalities and reduced energy production during exercise is belied by other ME/CFS studies. (Image of an ME/CFS patient doing an exercise test at Workwell)

Deconditioning…

“Physical deconditioning over time is an important consequence.” the authors

Just when we thought the deconditioning argument was over, it reared its head again. There’s no question that deconditioning must be present, at least on some level, in many people with ME/CFS. The bigger question is whether it’s relevant in a pathophysiological sense; i.e. whether it’s causing the abnormalities in energy production found during an exercise, the low functionality found in the disease, and even the disability present.

The study asserted that it is relevant; i.e. that it is causing the low energy production, workload, etc. scores found during the exercise test, and is producing “the functional disability” found.

“With time, the reduction in physical activity leads to muscular and cardiovascular deconditioning, and functional disability.”

It’s important to note that the authors did not say that lazy ME/CFS patients were not exercising enough or that they had illness beliefs which resulted in them not engaging in enough activity. Instead, they laid the blame for deconditioning on biological factors (immune, metabolic, autonomic, endocrine) that are impairing people with ME/CFS from engaging in much activity.

The authors went out of their way to ensure that no one would miscontrue their results to endorse the idea that exercise or CBT could solve ME/CFS. They stated that practices like

“exercise, cognitive behavioral therapy, or autonomic directed therapies, may have limited impact on symptom burden, as it would not address the root cause of PI-ME/CFS.”

Their assertion that deconditioning was responsible for the cardiovascular abnormalities found, though, seemed like a step backward. How important a step backward is unclear. Those cardiovascular abnormalities form the basis for the disability findings that many people with ME/CFS rely upon to survive. Since the authors argued that biological findings ultimately result in deconditioning, it’s not clear what effect they will have.

Because the low V02 max was correlated with an increased incidence of type II :1 muscle fiber ratio fast-twitch muscle in ME/CFS patients, the authors asserted it was evidence of deconditioning. They concluded this based on samples from 7 ME/CFS patients and 5 healthy controls.

Their conclusion that deconditioning is causing the cardiovascular abnormalities found in ME/CFS also flies in the face of the findings of several ME/CFS studies.

Workwell asserts that it’s impossible to say anything about deconditioning in ME/CFS (or postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome for that matter) without doing a two-day exercise test. Both ME/CFS and POTS are something of anomalies in the medical world: one-day tests that suggest that deconditioning plays a role may be accurate in other diseases but not this one.

Two-day exercise tests in ME/CFS indicate that something other than deconditioning is producing the cardiovascular abnormalities found in the disease. The fact that deconditioned people show similar results on both days of the two-day exercise test results, while ME/CFS patients show a significant drop on the second day, indicates that people with ME/CFS have a fundamental metabolic problem the deconditioned people do not. (They cannot produce energy without at the same time whacking their ability to produce energy.)

Other findings are at odds with the authors’ conclusions. David Systrom’s large, invasive exercise studies found two factors in ME/CFS (increased peak exercise cardiac output and low heart filling pressures) that are not only not found in deconditioning but are opposite to those found in deconditioning. The authors reported that their findings, “definitively eliminates (the) possibility” that deconditioning is causing the exercise abnormalities.

A Dutch study examining the electrical muscle activity concluded that the increased muscle fiber conduction they found in ME/CFS was opposite to the reduced muscle fiber conduction found in deconditioning.

A large Dutch study found that the high heart rates and reduced stroke volumes during a TILT table test that could be interpreted as the result of deconditioning were not associated with fitness; i.e. both very low-functioning and higher-functioning patients had similar findings. Even the more fit ME/CFS patients – who could not be experiencing deconditioning – had significantly lower heart rates and stroke volumes than the healthy controls; i.e. deconditioning was not causing their cardiovascular abnormalities.

On a personal note, during an exercise test, my heart rate at the anaerobic threshold indicated that I had only a small window of healthy activity. My oxygen consumption at the anaerobic threshold indicated I probably wasn’t generating enough energy to comfortably do the normal tasks associated with daily living. Yet, my average daily step count over the past year (probably higher than it should be) – is 7,860 – or is a bit higher than the healthy controls in the study (!). My cardiovascular and metabolic abnormalities cannot be due to deconditioning.

THE GIST

- The recoveries of several people in the 4 years after the study, plus the lack of orthostatic intolerance, small fiber neuropathy, cognitive differences, etc., between the ME/CFS patients and the healthy controls have raised questions about patient selection. The patients underwent a rigorous selection process which required that they meet the IOM criteria or ME/CFS, did not have any confounding factors, and were vetted by a group of well-known ME/CFS experts.

- The coronavirus pandemic impacted the study more than we knew. Only 8 ME/CFS patients and 9 healthy controls completed the second week of the study which focused on pathophysiology.

- In what can only be described as a major missed opportunity, the study employed an exercise test but did not use it to explore the cause of post-exertional malaise by comparing results before and after exercise.

- Even with these shortcomings – the small and truncated study, the less than a representative sample of patients, and the lack of interest in PEM – the study nevertheless provided many interesting and, I think, potentially helpful findings. The fact that it was able to do so with so few patients was encouraging.

- Two important prior findings in ME/CFS – that immune activation and immune exhaustion are present – were validated by the study. An increase in the percentage of naïve and a decrease in switched memory B-cells in the blood could suggest the body is trying to fight off an infection and/or has an immunodeficiency problem.

- A major takeaway from this study is going to be the huge split between the results of the males and females in virtually every category including the immune system, metabolomic, muscle, and gut fundings. The study indicates that separating men and women in studies could lead to far more valuable results.

- Dr. Anthony Komaroff stated the immune findings were fully consistent with existing research and that the study provides compelling evidence that the immune system is chronically activated: “As if it’s engaged in a long war against a foreign microbe, a war it couldn’t completely win and therefore had to continue fighting.”

- The ME/CFS group had reduced cerebrospinal levels of dopamine metabolites (DOPA, DOPA) as well as a serotonin precursor (DHPG) – two “feel good” brain chemicals. The authors called this evidence of “decreased central (brain) catecholamine biosynthesis” in ME/CFS. A metabolomic analysis of the spinal fluid indicated altered levels of dopamine, tryptophan, and butyrate metabolites. Problems with dopamine, in particular, could affect many symptoms in ME/CFS including movement, attention, sleep, and cognition. Ron Davis at Stanford is currently exploring the role BH4 may play in the dopamine pathway. Women and men had different CSF metabolic results.

- The gene expression of the muscles in both men and women showed evidence of increased rates of oxidative stress – a potentially important finding, as several studies suggest that oxidative stress is wreaking havoc on the muscle membranes in ME/CFS. Once again, once separated, women and men, however, showed different abnormalities. The same was true of the lipid and gut findings.

- Importantly, though, even with the small samples, the researchers were again and again able to easily differentiate ME/CFS patients from the healthy controls – a sign they were on the right track.

- Even though less than half of the participants (8/9) ended up doing the exercise test, the study found that peak power, peak respiratory rate, peak heart rate, and peak VO2 (p = 0.004) were all significantly lower in the ME/CFS group. Plus, a lower heart rate reserve was found and chronotropic incompetence was found. The fact that anaerobic threshold (AT) occurred at lower levels of oxygen consumption fit with the idea that the aerobic energy production system in ME/CFS is impaired.

- The authors, though, asserted that while they believed that biological factors led to the deconditioning, the deconditioning was responsible for the cardiovascular abnormalities and the disability found in ME/CFS. That conclusion flies in the face of numerous ME/CFS studies, some of which have found directly opposite findings than those seen in deconditioning.

- Avindra Nath, the lead author of the study, concurred that deconditioning was not causing ME/CFS, stating, “The findings underscore that the symptoms cannot be explained by physical deconditioning or psychological factors. We can very emphatically say that we don’t think that’s the case” he says, “There are true biological differences.”

- Conclusion – The small size, the missed focus on PEM, the easily misinterpreted “effort preference” finding, the deconditioning interpretation, and the conclusion that the muscles were operating normally in ME/CFS (see the first blog) raised questions about the study.

- Coming up – Part III: the big picture, potential treatments, and the future.

- Appendix – if you want to dig even deeper into the “effort preference” issue – check out the appendix to the blog

Avindra Nath has publicly stated that did not think deconditioning was causing (and for that matter neither do the other authors). was determinative. Nath told Oregon Public Radio:

“The findings underscore that the symptoms cannot be explained by physical deconditioning or psychological factors”, says senior author Dr. Avindra Nath, clinical director of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. “We can very emphatically say that we don’t think that’s the case” he says, “There are true biological differences.”

Conclusion

The studies intention was to illuminate key factors that can be followed up on. While it wasn’t perfect it did achieve that goal

The small size, the missed focus on PEM, the easily misinterpreted “effort preference” finding, the deconditioning interpretation, and the conclusion that the muscles were operating normally in ME/CFS (see the first blog) raised questions about the study.

It was remarkable, though, given the small sample sizes, to see the study again and again easily differentiate ME/CFS patients from healthy controls. It was equally remarkable to see the impact that separating the sexes had. While the study had several problematic features, the goal of the study – to provide avenues for further exploration – seemed to have been abundantly met.

The NIH will also be hosting a symposium on the study where the public will be able to answer questions.

- Next up – Part III – the Big Picture, potential treatments, and the future.

Appendix: More on Effort Preference

I’ve been obsessed with the thorny “effort preference” finding. Here are some more thoughts on it for those who want to dig deeper:

“Their brain is telling them, ‘no, don’t do it,'” says Nath, “It’s not a voluntary phenomenon.”

A lot of the rest of the blog comes from the supplemental notes from the study where the authors thoughtfully provided ME/CFS patients’ experiences to help explain the findings.

The “effort preference” issue – that it rather than muscle fatigue is driving the “motor behavior” in ME/CFS – has understandably produced a lot of upset in the ME/CFS community. My reading of the paper, and Nath’s comments after its publication, indicate to me that the authors do not intend for the “effort preference” issue to be considered primarily in psychological terms. Nor has psychology been a focus in the media reports that I’ve read. Some of the wording did leave open the door to let some psychology in though, In this section I want to point out some possible issues with “effort preference” in the paper.

It does not appear, to me, at least, to be a particularly robust finding. For one, if I’m reading it correctly, the authors went through five different models before they found one that could fit. The study found that average button press rates declined significantly over time in the ME/CFS participants, but only for the easy tasks. Button press rates were the same in the hard tasks for the ME/CFS patients and HCs.

While the ME/CFS patients punched the buttons as quickly as the healthy controls during the hard task, however, they were less likely to complete hard tasks “by an immense magnitude”. Instead of concluding that the ME/CFS patients suddenly “hit the wall”, the authors concluded that ME/CFS participants “reduced their mechanical effort” by pacing during the hard tasks. This conclusion seems belied by the fact that ME/CFS patients were working as hard as the healthy controls; i.e. they were punching the buttons as quickly as the healthy controls – they simply didn’t complete nearly as many hard tasks.

Did the ME/CFS patients suddenly hit the wall during the effort test, or were they pacing?

The authors referred to a patient report to back up their pacing interpretation.

“You have to make a conscious choice of how much energy [to use and] whether or not something is worth crashing for. It’s hard because no sane person would ever (choose) to suffer and … that’s what you’re doing [by choosing] an activity that … will make you crash. You are going to suffer… You have to decide what gives you meaning and what is worth it to you.”

I would argue, though, that that assertion has been misapplied. If anything gave the ME/CFS patients “meaning”, it was the opportunity to be in a study committed to solving their disease. One would think they would be more committed to pushing through their symptoms than the healthy controls.

The authors discarded that idea, though, by asserting that it was the lack of encouragement during the cognitive test that made the difference. When encouraged during the exercise test, the patients pushed themselves (and did not exhibit a difference in “effort preference”), but lacking that encouragement, they held back during the cognitive test. To suggest that both the ME/CFS patients and the HCs responded to encouragement during the exercise test but, left on their own, the ME/CFS quickly pooped out was quite a judgment call and rather demeaning.

My guess is that the ME/CFS patients were probably so invested in finding out what was wrong with them that they pushed themselves to the limit. I know I would have. If the authors had looked more deeply, they might have understood that crashes in ME/CFS can occur very quickly and without warning.

The paper asserted that both “conscious and unconscious behavioral alterations to pace and avoid discomfort may underlie the differential performance observed” and, of course, that must be true. People with ME/CFS consciously (and smartly) avoid activities that experience has taught them are going to make them worse.

The study the paper linked to in this section, however, indicates what treacherous territory we’re in with “effort preference”. It’s a Dutch study that found an activated motor cortex (and reduced prefrontal cortex activity) in ME/CFS but appeared to hang those findings on “prior beliefs about physical activities”.

“These findings link fatigue symptoms to alterations in behavioral choices on effort investment, prefrontal functioning, and supplementary motor area connectivity, with the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex being associated with prior beliefs about physical abilities.”

Effort preference is clearly a slippery slope.

On the other hand, the authors couched the last part of the effort preference/motor cortex/TPJ finding in a way that makes sense to me (if I’m reading it correctly). “TPJ activity is inversely correlated with the match between willed action and the produced movement”; i.e. High levels of TPJ activity are associated with the ability to willfully carry out movement. Low levels of the TPJ activity – the kind found in ME/CFS – make it difficult to willfully carry out movement. Bingo.

For his part, Nath doesn’t seem to endorse the “voluntary pacing” interpretation. He stated that the brain is producing the effort problem.

A region of the brain that’s involved in perceiving fatigue and generating effort was not as active in those with ME/CFS. “Their brain is telling them, ‘no, don’t do it,'” says Nath, “It’s not a voluntary phenomenon.”

Likewise, Tony Komaroff believes the paper shows that a brain abnormality is making it harder for those with ME/CFS to exert themselves physically or mentally. “It’s like they’re trying to swim against a current” – the most accurate description I’ve seen of ME/CFS in quite some time.

Hey Cort, what evidence is there to suggest that the second week of the study was impacted by the pandemic? For example I don’t see how sending actigraphs to someones home would be something affected by the pandemic (or why only half of participants have this data).

The actigraphs would be something different. I don’t know why everyone didn’t do them. Everything was shut down for quite a while during the pandemic – this study was no different in that regard. Since first they did the first week then quite a bit of time passed before anyone did the second week, it makes sense to me that more people would have missed out on the 2nd week once the study was shut down prematurely.

At this point, we need a miracle

Thanks Cort. One small correction —

From The Gist: “The authors, though, asserted that while they believed that biological factors led to the deconditioning, the deconditioning was responsible for the cardiovascular abnormalities and the disability found in ME/CFS.”

^Should be “was NOT responsible” right?

Actually no. They believed while the biological factors lead to the deconditioning, they believed the deconditioning was responsible for the cardiovascular abnormalities – at least that’s how I read it.

Wow, I’m with you, Cort, on the issue of “effort preference.” Saying it’s demeaning is to put it mildly! I was a college athlete, and won awards for pushing myself more than others. That has always been an intrinsic quality of mine.

Unfortunately, this has made me live most of my 27 years with ME/CFS without pacing. Any day I had a little more energy, my mind would come up with a list of things to do. It’s automatic. It never dawned on me to choose NOT to use every bit of energy everyday. I expect the same is true for most of us with ME/CFS.

I also misunderstood pacing. Until recently, I thought it was simply about avoiding the really bad days/weeks after pushing past my limits. I didn’t realize I could permanently lower my functional baseline by repeatedly pushing past those limits for family events, household projects, etc.

The notion that we choose to avoid exertion, leading to deconditioning, and thus to major symptoms is offensive, full stop. I now turn down travel and family gatherings because I no longer have the ability to push like I once did. It’s not in me. I still live by doing as much as I can each day, while trying to avoid a major crash, because it gives value to my life. That’s something I can’t live without. Sad that so many people see us as simply lazy or unmotivated.

I agree with you, Deanne. I know from experience that I didn’t lack effort. I tried too hard to keep up my normal routines. Looking back, I could pinpoint how the times I was the most physically active correlated to the steepest declines in my overall abilities. It was like descending a stairway with several flat landings between the downward steps. After ~ 10 – 12 years, I finally learned to proactively think daily about limiting my activity and pacing so I wouldn’t continue to get worse. And still I end up in the push/crash cycle more than I’d like because I tend to be a doer, wanting to finish what I start rather than strictly pacing. I had to learn – am still learning 23 years later – to deal with was the frustration of not being able to “just do it”.

It’s actually not about lacking effort. We keep getting this backwards. This study suggested that the effort “button” is turned way up in ME/CFS and one consequence of that is that motor cortex not activating the muscles so that they can work. It’s not a bad hypothesis at all.

It is interesting though Cort. I do wonder if the “effort preference” idea is really just what constitutes sprinting versus endurance for ME/CFS compared to healthy controls.

I’m a moderate case in regards to ME/CFS. If I wanted to, I could do normal stuff for a short period of time, and then pay with PEM. What exactly is “normal stuff”. A few years ago, I was helping my then young daughter onto waves (surfing) in the middle of summer. This is the only time of the year I can handle the water temperature, wearing a wetsuit, and I live in the sub-tropics. It was a really busy surfing break, very low tide, and there was a collision of two surfers nearby. One went down hard in shallow water into a sand bank, head first as it turns out. He came up and was groaning in pain and obviously in big trouble. I asked if it was his heart as I moved towards him, and he said no, it was his back. So I had to initiate a full spinal rescue, as the first responder, in three feet surf (not big, but very tricky all things considered). That involved a lot of different stuff, including holding a substantial portion of the bloke’s body weight whilst supporting and securing his head, neck and spine until others arrived. We then sunk his board under him, used that as a spinal board and carried him to the beach (not floated, carried, about 70m). I was at the head end, so carrying at least half of his body weight, through a couple of feet of water. I was seriously worried about passing out as this all happened, but luckily I didn’t. My heart rate was maxed out whereas normally it only takes a small period of time above 110 BPM and PEM will kick in the next day. The surfer did have fractured L3 and L4 vertebrae, but fortunately no spinal cord damage.

I tell this whole story because the context of it explains the extent to which normal pacing type thinking just wasn’t a consideration in this situation. I went down hard with PEM the next day (actually I felt like rubbish as soon as the adrenalin wore off, but a lot worse once the PEM kicked in).

I see the above situation I found myself in relating to the “effort preference” theory stuff because I don’t see any consideration of context in that theory. Specifically, I mean context of PEM in ME/CFS. It takes a really exceptional situation to make full capability effort happen for me these days. But I wonder if the ME/CFS brain’s response is fundamentally any different to that of healthy people when “knowingly pushing too far”. For instance, give a serious swimmer 10 x 100m freestyle at maximum effort spread over two weeks, and you’ll see near personal best times on each occasion. Give the same serious swimmer 10 x 100m freestyle repeating on the 1 minute 30 seconds, and unless they are an Olympic distance swimmer (or something near to that), they are in for a painful 15 minutes of just scraping through. No personal bests anywhere to be seen. If they attempted to do even one personal best in a set like that (at the beginning of course), I strongly doubt they would make it through the remainder of the set on the time limit. So if a healthy swimmer holds back from total effort in a set like that, is that their brain behaving in a problematic way or is it just their ability to accurately predict the reality of the future (and survive the set).

The hand grip test, for ME/CFS, reminds me of a healthy swimmer trying to set a personal best at the beginning of a 10 x 100m set on the 1:30. Sure, if you were inexperienced, you could do the personal best, but you would very quickly learn not to, because you inevitably bomb out of the rest of the set. I’d be very interested to know what existing studies there are for “effort preference” for healthy people being pushed to do things that are simply beyond their limits? I’m assuming there must be, otherwise how does anyone know what is normal. For people living with ME/CFS, we know (not think, know) that we are going to bomb with PEM after many tasks that healthy people don’t even consider effort. ME/CFS context (read reality) is completely different to healthy people’s doing these tasks. I’d want to see evidence that the way ME/CFS brains work in terms of “effort preference” when managing PEM is significantly different to healthy peoples’ brains attempting something they can’t do.

There’s a reason people don’t go mountain climbing with a broken leg. But if you’ve read “Touching the void” you know it is possible for some, given certain death as an alternative. At the moderate level of the illness, hand grip tests are not climbing a mountain, PEM isn’t a broken leg, and death isn’t imminent in an NIH study (pretty sure that’s right). On the other hand, PEM is way worse than the consequence for a healthy swimmer of sprinting the first leg of a endurance set and bombing out. Having written all this rambling argument, and thinking about the complete absence of PEM in the NIH study, it makes me wonder if those involved in the grip test “effort preference” theory just don’t comprehend PEM’s significance.

This illness is suffered by many A type personalities, athletes and workaholics like me and at some stage burnout was believed to play a part. We are some of the strongest and least lazy people on the planet, unfortunately we have been victims not only of the English Government and insurance fraud labeling our illness as psychological and a result of deconditioning but many of our own extreme feats and levels of effort, endurance and mental strength, pushing ourselves and our bodies way beyond the average person, have unfortunately led to our downfall. Society also hero worships those who push beyond their limits and is highly achievement and work focused, labelling those who don’t or can’t as bludgers. Self care is a relatively new movement.

As for me, I think a sort of ‘initial deconditioning’ was happening WHILE and BECAUSE I was still working ft at a very physical job and trying to live a full life, as a RESULT of the biologic mechanisms of the disease.

The harder I worked and willed myself through activities and exercise, the worse my condition and the weaker I got – and this was happening over years BEFORE I ever heard of pacing or even MECFS! Like so many of us, my body was deteriorating WHILE I did the very things that should have made it stronger.

When I finally did my 2day CPET, resulting in an AT of 81bpm, I had ‘work-ethicked’ my way into ‘rolling’ PEM and mod/severe status.

MECFS certainly did not manifest as a result of ‘deconditioning due to inactivity/pacing/’effort preference”.

Subsequently, Workwell said yes, some deconditioning would likely happen due to the aggressive pacing I need with my low AT, but that is the ‘lesser evil’ to continuing to worsen the underlying condition, possibly permanently, by pushing and staying in PEM. Theory is, by adequately pacing and stopping the PEM, my energy system can gradually start to recover – THEN I can start slowly reconditioning without further damage. I think this approach is working for me, though its very very slow going.

Glad its working and my experience was similar. My muscles didn’t have time to get into a deconditioned state as I was getting ill. I kept pushing as hard as I could for a long time. I was in school, walking pretty long distances between classes where I went to college (UCSC)…..

The authors did not say that deconditioning caused the other parts of ME/CFS: we’ll what they believe those are in the last blog – but the cardiovascular abnormalities and the “functional disability” yes! and that functional disability aspect is clearly wrong.

Like you, I developed my first symptoms at a point in my life when I was very active, fit, healthy and working at an outdoor job full-time. And like you, I’d never heard of ME-CFS or pacing, so went through the same cycles of exertion-crash-recovery without understanding why. My “exercise preference” was certainly not a conscious choice in my last crash. I was training daily for a half-marathon and enjoying it, but noticing that there was a definite pattern of losing speed after a certain number of kilometres, no matter how hard I thought I was exerting myself. Now I think that was my brain slowing me down pre-consciously to conserve energy. Needless to say, my conscious mind decided to override it, with predictable results. If that’s how the authors define “exercise preference”, then it makes total sense to me, but I still dislike the term because it implies that a conscious choice is being made.

Yeah, this gotta be drilled into every MECFS patients and researchers: trying to maintain a semblance of normal life is the single biggest mistake. I consider myself recovered, and I still have the same issue. Every winter, I get progressively weaker, rather than stronger like normal people, as the skiing season progresses. I’m a basket case by the end of the season and I have to hit the road to re-recover.

The concepts of central fatigue and interoception are interesting theories but not established bedrock science. This study was conducted for deep phenotyping. It is an over reach by authors to draw conclusions from the data. It should have been presented as theories to consider. It was also very disappointing that they didn’t elaborate at all about such important findings as immune dysregulation, persistent antigen and dysbiosis. These are concepts sited in other neurological disorders such as Parkinson’s disease and multiple sclerosis. The authors also need to defend why they chose Modified effort expenditure for rewards task as part of their study design. Would they include a psychology based test on a study of other neurologic conditions?

I don’t mind their trying to link the hand grip test, brain scan and effort test together. I would like to know why they chose the EFfrt test in the first place as I don’t remember seeing it before. They did try to link the gut, immune dysregulation with the other findings and I will cover that in the next blog. 🙂

““The findings underscore that the symptoms cannot be explained by physical deconditioning or psychological factors”, says senior author Dr. Avindra Nath”

One troubling aspect of this study for me has been the people involved in this are saying something different from what the paper actually says. The abstract of the paper clearly attributes the lack of performance to “conscious or unconscious pacing”; it declares MECFS is “centrally mediated” but not a central fatigue. It considers deconditioning a major factor. Taken together, they point to MECFS as a functional disorder. Yet, they are minimizing these findings in the public and emphasize biological differences.

I’m in the camp that says let the evidence fall where they may. And I don’t mind MECFS as a functional disorder if that would lead to the solution. But they are engaging in politics of avoiding that phrase, at least partially. I think they should be more honest about what they think/found so that we can tackle the findings head on.

To be fair, there are things in this paper that I agree on. MECFS patients are not incapable of generating power when they are not in PEM state. The CPET test is the proof. There could be something about dopamine and norepinephrine, based on my anecdotal experience with novel stimuli and positive stress/challenge. But this paper, taken as whole, does have an overtone of MECFS as a functional disorder. I think we shouldn’t paper over that.

As for the topic of missed opportunities, I think they could’ve repeated EEfRT and hand grip test after the CPET to see the difference including the catechol level, and then figure out the cause of the difference. Instead, they ran these tests only in the rested state and concluded that MECFS fatigue is psychological lack of effort.

It is fair to ask, “Why the doublespeak?”

Exactly which science discipline would view this as a thorough, appropriate, or well-designed study, much less one with mega-funding and anticipation? Is the backtracking to detract from the absurdity of conflicting statements within the analysis?

I think with the number of authors on here, and the high caliber journal, it is very possible some authors pushed for/believed that having a nice tidy bow explaining this and a mechanism would be more impactful or even the peer reviewer comments as part of the journal process pushed them in that direction.

As a former researcher and someone that regularly works on scientific manuscripts, this happens oftentimes. Is it ideal? No. All authors should be fully on board with what is stated in the publication but with so much data in this paper and so many authors I can see it easily happening that maybe Nath doesn’t think that was a central tenet of the pathophysiology hypothesis even though it seemed prominent in the paper. Maybe he recognizes more the value of publishing this full set of data and trying to later speak to more concrete conclusions from it? Just a guess.

Thanks. I agree, there is something to do with too many cooks spoiling the broth. Embarrassing.

My guess would be somewhat similar, except that the dichotomy naturally evolved from the composition of the team rather than calculated. This paper is the product of Nath who believes in physiological aspects of MECFS — at least he has been emphasizing that in the public — and Wallit who is firmly in sociopsychobiology/FND camp (based on his history). So, the two -track-minded paper basically concluded that physiology (biochemical alteration) and psychology (hypothalamic functional alteration) together constitute the phenotype of MECFS. And Nath is now out selling it as purely physiological while the paper says it’s both physiological and psychological. He might succeed by claiming the psychological alterations arise from the physiological changes. But that is basically the position neo-FND camp, which contradicts my position, and most of MECFS patients, that pacing is a prudence, not an (irrational) fear that impedes daily functioning.

Komaroff wrote for Harvard Health on this study yesterday. Article HEADLINE:

Is chronic fatigue syndrome all in your brain?

It’s inexcusable.

I think Nath is accurate here – the paper does not say that deconditioning is causing the disease or causing all the symptoms – they say it’s part of it – and not the major part. From what I can gather it is the last stage effect of having this illness – so yes they believe does impact the functionality but it doesn’t the cause of the illness. The cause comes first – deconditioning is the result of the cause. That’s how I understand it.

Similarly, the paper doesn’t state that psychological factors cause the disease or can explain the symptoms. It did not find any evidence that psychological disorder caused ME/CFS and explicitly stated that. So if the question is “are psychological factors causing ME/CFS; i.e. is it a psychological disease – I think Nath answered correctly.

Could ME/CFS be impacted by psychological factors? Of course, but I imagine that any disease could be.

Functional disorder seems to refer to a condition which the medical profession cannot at this time explain but which reduces functioning….

“A functional disorder refers to a condition where nervous system symptoms cannot be explained by a specific neurological disease or other medical condition. Despite lacking a clear pathophysiological basis, these symptoms are real and significantly impact a person’s ability to function.”

A very broad term!

“Similarly, the paper doesn’t state that psychological factors cause the disease or can explain the symptoms.”

I’m not so sure about that. The fatigue in the grip test was explained as something caused by “conscious or unconscious pacing”. That sure sounds like psychological to me. If it was motor cortex controlling or PTJ malfunctioning without consciousness, we shouldn’t be able to over-exert and trigger PEM. But we do, way too often. I know I have, about a million times. And we know our struggle in PEM is not for the lack of effort. (I still don’t understand why they came to the conclusion that it is not a central fatigue. I still think PEM fatigue is a central fatigue just like flu fatigue, so I’ll have to re-read the paper to figure it out why when I get my brain back.)

FND, these days, is claimed to include physiological changes, according to some people (https://neuro.psychiatryonline.org/doi/abs/10.1176/appi.neuropsych.20220182?journalCode=jnp). Maybe this paper will end up calling MECFS an FND with physiological changes. I’d be wary of that.

Right – I may be splitting hairs but the both “conscious and unconscious” part means it can’t be all psychological and you bring up a good point – the “brake” if that’s what it is – can be overridden. That makes sense – we can probably over-ride all sorts of things for a time if necessary. Think if the opposite was true – we’d be like a car without gas – no ability to move at all. While some people get to that point – it’s unusual.

Exactly.

The positive stress / challenge thing is REALLY interesting. I often feel so much more energised when I travel somewhere new and exciting, for example.

Some people who experience this have discovered mould in their regular dwellings. The refreshment can often be the reaction to its absence. Not discounting the power of positive thinking, but the Cellular Danger Response happens in the midst of many things. Just a thought.

Yeah, that’s a possibility. The apartment that I live now if full of black mold in the winter, LOL. I clean them with my bare hands, and it doesn’t do a thing to me. Maybe I should sniff it and see what happens? I’ve been living in a half dozen different places though, and the result has been the same wherever I go.

The “refreshment” could be a bit more than positive thinking. Novel stimuli and positive stress unleash a slew of biochemicals that are often implicated in MECFS. And the difference is actually measurable: I’ve been able to do about twice as much without triggering PEM when I’m on the road or move to a new city. But, again, it’s a just an anecdote with no evidence.

We have to celebrate those stolen moments of revival at any level. Long may they last.

Yep, I’ve tasted freedom and I ain’t going back to the prison.

It took me 7 years, but that’s how I recovered, I believe. (Just a belief, no evidence). I live on the road for months, come back home, crash for a week or so, relapse back to steady MECFS state, rinse, repeat year after year. Certainly not an easy thing to do for an average MECFS patients, both physically and financially. I’ve been lucky in that regard. How’s that for an effort preference? 🙂 I was single-mindedly driven to escape the MECFS prison at all costs.

Reduced activity of TPJ raises more questions. What is responsible for reduced TPJ activity? Is it decreased cerebral blood flow? Is it related to immune dysregulation? Is it reactivated herpes virus? Is there any post mortem studies that specifically examine the areas of the brain mentioned?

“blood oxygen level dependent (BOLD) signal of PI-ME/CFS participants decreased across blocks bilaterally in temporo-parietal junction (TPJ) and superior parietal lobule, and right temporal gyrus in contradistinction to the increase observed in HVs”

I don’t ever remember the TPJ mentioned with regard to ME/CFS. The authors do have an grand hypothesis which they believe could explain the TPJ. I don’t recall it at the moment but will post it in the last blog.

TPJ didn’t light up because the patients did not exert enough, according to the authors. That’s how they surmised that pacing, or the fear of PEM, not real fatigue, was preventing them from exerting. Then they mentioned patients’ ability to reach the maximum exchange ratio with encouragement in 1-day CPET test as the further evidence of the lack of effort. We wouldn’t know if TPJ would’ve lit up if patients were encouraged to exert, like they were in the CPET test, since the grip test was unsupervised.

I can see how you could conclude but that is not my reading of it – and thank goodness for that. In a later section of the paper underneath the model this is the author’s final conclusion.

“Altered hypothalamic function leads to decreased activation of the temporoparietal junction during motor tasks, suggesting a failure of the integrative brain regions necessary to drive the motor cortex.”

This is apparently why Nath did not call this voluntary.

Isn’t it interesting that the effort preference issue did not show up during the maximal exercise test – the greatest test of them all?

That particular sentence could be interpreted as a polite way of saying “Conscious and unconscious behavioral alterations to pace and avoid discomfort may underlie the differential performance observed”.

Hypothalamus is responsible for reward-motivated learning (such as Pavlovian conditioning). So, it could be interpreted as saying hypothalamus functioning was altered by the fear of PEM, which led to under-exertion and therefore decreased activation of TPJ.

Also note the word “concomitant” in front of “alteration of hypothalamic function”. The sentence is not saying that altered hypothalamic function is the result of “altered biochemical milieu” that proceeded that sentence. Instead, it is saying that hypothalamic alteration is happening at the same time as the biochemical changes.

I mean, it could even be a coincidence. We know thanks to Visser et al that many people with CFS have reduced blood flow to the brain. Maybe these parts of the brain just happen to bear the brunt of that reduced blood flow due to anatomy.

This seems like a mysteriously badly designed study which yielded some interesting corroborative research findings in spite of deliberately inappropriate study parameters.

It almost needs a pro/con list to describe it concisely.

Really appreciate the extra commentary on “effort preference”.

It is a term so irresponsible and damaging that it should never be uttered in any literal sense again. The study design using a few mild subjects is too odd and flimsy for a novel hypothesis like that persist. Moreover, the practical risk of medical malpractice from its misinterpretation cannot be underestimated: There are people who are never offered referrals to specialists once they receive either an ME/CFS or FND diagnosis.

We also face the confusion brought about by many researchers and journalists who insist on reporting Long Covid findings differently to facsimile findings in ME/CFS research, as if one will take the crown of “physical consequence of immune derangement” whereas the other will be the ugly stepsister who is “poorly understood” or as the Guardian put it last week in response to this NIH paper, linked to “brain imbalance”.

Unfortunately, the science of ME/CFS cannot be decoupled from its social history.

Possible “persistent antigenic stimulation” and “downregulation of mitochondrial processes in the muscle” should be salient and publicized findings.

Looking again at the summary…

If two-day CPETs show a significant drop on the second day, indicating that people with ME/CFS have fundamental metabolic problems and cardiac abnormalities when deconditioned subjects do not, then their impairment is again not “functional”.

The Systrom and Dutch studies mentioned finding ME/CFS results which are opposite to results found in deconditioning also cast doubt on using a deconditioning hypothesis about incomplete CPETs in the recent study characterized by limited results.

Low stroke volumes and smaller hearts are found in POTS. A person’s POTS symptoms vary day to day based on diet and activity (electrolytes balance, whether or not they have had a massage, or performed dynamic movements). Again, ham-fisted and flimsy study results may be the issue here.

Also, the fact that “anaerobic threshold occurred at lower levels of oxygen consumption” in people with ME in this study anyway, and that “significant differences between (people with ME/CFS) and healthy controls showed up consistently” when men and women were compared separately to health controls is fundamental to the definition of the disease as distinctly physical.

Deconditioning in ME/CFS needs to be compared to deconditioning in the absence of the disease. Referring to the disability in ME/CFS as “functional” should be condemned as a conclusion from only seven subjects, with no evidence from a larger subject group and no longterm evidence of what effect reconditioning efforts have on the muscles and immune responses in people with ME.

If authors admit that deconditioning is the result of biological factors (immune, metabolic, autonomic, endocrine) impairing people with ME/CFS from engaging in much activity, then the resulting disability is not “functional”.

Thanks again for dissecting such a mess.

What was their definition of orthostatic intolerance at the time of this study? Was it based on vitals? Or symptoms? Just ruling out POTS or low blood pressure does not rule out OI as many have “POTS without the T” or have “chronotropic incompetence” (ala Campen, Rowe)

They actually did not rule out POTS and did find it in about a 3rd of the ME/CFS patients. They used a standard definition of POTS and they did a nice long TILT table test. They also found evidence of it a smaller but still significant number of healthy controls. That’s why they stated they did not find increased rates of in ME/CFS vs the healthy controls.

I am talking about orthostatic intollerance, which might include POTS but is not the only form. When they said they did not find orthostatic intollerance what were they refering to?

I agree this needs to be spelled out (haven’t checked yet whether it is). I am also constantly amazed that a lot of people who should know better, such as doctors and scientists, seem to think that POTS and orthostatic intolerance are the same thing.

I don’t believe they measured cerebral blood flow or end-tidal CO2, so that means they would have missed anyone with OCHOS or HYCH (syndromes discovered in the past decade by Dr Peter Novak).

Yes! Exactly. How can lead researchers on such a project not know this.

My understanding is that not many of the tools to accurately measure cerebral blood flows are available and I suspect they did not have one. This was not an assess everything in depth study – that would be too much. Instead, it assessed a very wide variety of factors.

This feels like another tiny, frustrating, messy and potentially dangerous study. (Effort persistence. Thanks a bunch. It doesn’t matter how that is now downplayed or explained, the term is out there and gives another opportunity for the psych brigade to cling on to ME.) So many missed opportunities. Thank you for your persistence Cort.

Well said Louise! That’s exactly how I feel. All those years and $$s for these outcomes? Ugh, not only extremely disappointing, but potentially sets patients up for being more misunderstood. “Effort preference” – words that should never have been published. They can explain and backtrack all they want but these words aren’t going to go away.

I agree that the “effort persistence” term is problematic in the extreme but I also think the psych ship has sailed. I compared the number of CBT/GET studies done over the past couple of years to prior years and found very few studies being done now. I think it’s time has passed.

The psych effort was never embraced by the US. While the UK and the Netherlands poured tens of millions of dollars into them, Ican’t think of single ME/CFS CBT study I doubt that will change. The study had many other findings – immune, metabolomic, gut that researchers can chew on here.

Hi Cort, I desperately hope you’re right. I’m in the UK, where it doesn’t feel to me as though we’ve fully shaken them off. I’m looking forward to reading Part III!

Sorry for long reply… I am also in the UK. In the past year, I have spoken to a new GP who said he helped on a podcast about the PACE trial and pointed out, “The funny thing is, everyone got better”. No they did not. That study had ties to the DWP.

Last month, a friend who has her GP’s mobile number (their families know each other) was asking about my switching to his practice whilst on speakerphone. “Why, what’s wrong with her?” He asked.

“Oh, ME? She’s not going to get different treatment at a different GP. ME isn’t real. It’s psychological. There’s no test for it. Does she have a lot of stress? Patients get stressed out and then have body pains and they start complaining and get depressed and stop moving, and it’s always difficult for doctors to deal with them because we have nothing to offer them. It’s in their mind.”

Yesterday, Dr. Weir travelled several hours to the Royal Lancaster Infirmary to remove the psychiatric sectioning under the Mental Health Act on a young woman with ME/CFS named Millie who cannot eat or drink and who is not being allowed a feeding tube. The hospital may have doubts about her “effort preference” and blamed her condition on anorexia behaviour, etc.

Her case is the third like it this month.

The issue is, Dr. Weir, Dr. Myhill, Dr. Claire Taylor… are all in their 50s or 60s. There are less than a handful of doctors who understand ME/CFS in the UK. Furthermore, off label treatments which are available in the U.S. are not allowed in the UK.

In some countries, ME/CFS is not even recognised as a disease or syndrome.

In such cases, irresponsible wording in such a prestigious setting only underpins clinicians’ incorrect conclusions – and they decide to wait for more evidence rather than to accept the implications of separate studies already published.

The Guardian really did call it a “Brain Imbalance” in their headline about this study.

Incidentally, when we think of misconceptions, frequently repeated line about ‘children not being affected by Covid’ means that there is no pathway to referral for long Covid for children in England. A Channel 4 documentary from one year ago cited over 120K children affected by it. Still, GPs have to ask for advice from Paediatrics departments just to instigate more thorough blood tests to decide whether or not to proceed to further investigations. But what investigations? These children will not get anything like tilt table tests or screening for clotting and autonomic nervous system dysfunction at David Putrino’s lab.

The outrage, I find, seems to be among people who are not mildly affected, and those with fewer options for care. One lady in Australia described Nath’s study as “a hit piece against people with ME which will set patients in disability claims and research trials for drugs and therapies back another 30 years”.

The Bateman Horne Center response was not overly impressed, either.

Was this the first NIH study of ME/CFS like this in 35 years? When exactly is the do-over?

If only studies reflected what is being practised on the ground. ME-CFS patients continue to be dismissed, “psychiatrised”, and subjected to misdirected treatments every day. It’s good to hear that GET and CBT are falling out of favour with researchers, but it could take at least another generation of newly-minted healthcare providers to catch up with the evidence and understand how to provide appropriate care.

Honestly, you have an amazing knack for making research intelligible! I could never wade through it without your skills. Thank you so much.

Thanks!

I’m lost. I can only imagine how totally in the dark I’d be if I didn’t have help from Cort.

But when Cort is reduced to having to say, “For one, if I’m reading it correctly…,” it tells me that any attempt I make to do interpretation would be futile.

So my takeaway is that the FACT that I can’t interpret the study itself reveals how inadequate this study was. (But maybe this study will lead to other studies that I can read and be confident in my interpretation?)

I’d love to see a compiled list of “simple” questions we all have. For me, “Why do my eyes get dry after I walk through the grocery store?” And, “Why do my legs hurt after I have an intense telephone call?”

If I could understand the answers to these questions, then I would know how to respond to people who are asking about my illness, and they could walk away from our conversation with less skepticism.

Wow Cort, you did your homework. THX for your hard work. First your blog about metabolic disorders and now part 2 of the NIH study. Respect. It must have been quite a struggle. Honestly, I find the statements from the authors about deconditioning and the brain that says it doesn’t move a bit ridiculous and ambivalent, let alone scientifically sufficiently substantiated with this absurdly low number of selected patients. And nobody had POTS.

Professor Scheibenbogen found that approximately 30% of her patients had POTS, another study by Blijenberg 5%. Increased autoimmunity against certain receptors was found in this group and has been repeatedly confirmed. Nath has not looked at these autoantibodies and that is also not possible if there are no POTS patients. So this makes the autoimmunity in POTS/ME/CFS more plausible.

There will be a very large study carried out in England on this point.

Nath et al., didn’t nail ME/CFS at all!

Thanks! (It was exhausting but also fascinating :))

One of the weirder parts of the findings was that about 30% of the ME/CFS patients did have POTS! But about 20% or so of the healthy controls met the criteria for it as well. The POTS thing was more a healthy control issue than anything. I don’t know if they looked at Scheibenbogen’s autoantibodies or not actually.

It would be interesting to repeat the study with people that had ME/CFS for at least twenty years and compare the results. I’ve had FM for over thirty years. I never had POTS until three years ago when I had hip replacement surgery. Likely due to dysautonomia my blood pressure plummeted during the procedure, and I developed POTS shortly after.

Karen, are you aware that low blood volume due to loss of blood during surgery can result in POTS? For some people saline IV or Oral Rehydration Solution can help to boost blood volume. ORS works perfectly for me. Cort has written about it previously.

I could only say after 30 years of severe illness: “Nath, do you have a dollar for every ME/cfs affected person in the US”? what a redicolous tiny study (participants) to draw conclusions on. A verry verry tiny pilot study…. for excample geneteic, if the DECODEME study (GWAS) even had not enough participants (no more money) with their + 20.000 participants and as many controls from their biobank, say genetics is 10 years behind on onther deseases with ME/cfs, Beg the US to do at least 100000 patients study and similar biobank controls. If Long covid has allready wordlwide genetic studys working together over the globe. If precisionlife for ME/cfs finds there own now 20.000 patient samples to few for SNIPS and is replicating and beg the world to give their data wich excist… if DecodeME wants to excelarate further research… This dear Nath, is simply ridicolous. and yes ofcource man and women are different… that has long be said/known in research. Even i know it…who does not? If this is the research and the money spend…I hope for other researchers.

Yes, it was always going to be a small study – and it turned out to be a really small study – but I think there’s a silver lining here – even with this very small study – they were able time and time again to easily differentiate the patients from the healthy controls. That really surprised me. We rarely see that kind of sharp differentiation.

If I was the NIH looking at this I think I would conclude there’s really something there – really something to build on.

yes, i understand what you mean with time over time identification. but things must also be statistcly significant in research. And such a tiny study simply is not. if you see for excample the DecodeME study to get at there statisticly significant number…. And a silver line, they could have done so much more if they put really money in it. i really can not take it seriously. And they call themself center of excellence 🙂 . not excellent for me…

for who is interested because there is way way more but am to broken: https://precisionlife.com/news-and-events/precisionlife-and-metrodora-institute-partner?utm_campaign=Healthcare%20Diagnostics&utm_medium=email&_hsmi=295922502&_hsenc=p2ANqtz–pybMeyCid9Pk_vDyK-uw7Evor2-mqLisDnvKF2QRiLn3vXSB1q_L_fIJBKtoGXkt2HyRNe_VOqnbL7BcFkc67m341Tw&utm_content=295923751&utm_source=hs_email

Interesting about the dopamine. I’m pretty sure I have a lack of dopamine because I am much more functional in interest-based activities (those release dopamine I think). I sometimes get into a kind of tunnel focus/flow state on them (which is how the majority of my posts on this board happen ;)) and crash afterwards. I haven’t been sure if this could point to a late-onset ADHD with hyperfocus or if ME/CFS can cause ADHD-like symptoms, or maybe both.

Nice point! I really like the dopamine findings as well in part because they fit in with Andrew Miller’s basal ganglia study in ME/CFS – one of my all-time favorites! There was a ton of interesting stuff going on in that study.

Andrew Miller would be in my top 2-3 ME/CFS researchers. I think he’s got pretty close at times to ‘the answer’. Is he still doing research in the field?

I wonder who’s agenda is being followed with this study. The findings on the lack of mustle damage are in complete contrast with this recent study from Netherlands. They completed biopsies pre and post exertion which showed microclots in the muscles and mitochondrial problems with oxygen utilisation.

https://www.npr.org/2024/01/13/1224589127/a-discovery-in-the-muscles-of-long-covid-patients-may-explain-exercise-troubles?fbclid=IwAR3dxC54L4i7fS2gDXV5g6Qu13BA3LYQPtgjHCxR_yWvmc8f8H0Epn9Azbk

Agreed! They did very limited muscle testing.

It is nothing short of a scandal that the one symptom that categorically defines M.E. (Post exertional malaise) was not investigated (before and after exercise).

It was a big miss in my opinion. The study did, however, present the NIH with possibilities for further research – so it worked on that level.

Cort, have you heard whether there will be additional papers published from this study or did they put all the data in one paper?

MY understanding is that there will be additional papers. We’ll probably learn more at the Symposium.

I asked Nath this week about subsequent papers. He said:

“Yes they will come out. No definite dates.”

I then asked “ Should we expect to see these in Nature Communications as well?”

He said “who knows.”

🙂 Thanks!